The doorway to life

“We are Christians and Catholics not because we worship a key, but because we have passed a door, and felt the wind that is the trumpet of liberty blow over the land of the living.” So remarked G. K. Chesterton in The Everlasting Man, written shortly after his conversion to the Catholic faith. Doors, which serve a practical purpose in any house of worship, have always had deep religious symbolism in the Church. The first of the ancient minor orders was that of the porter, who before his ordination was urged by the bishop to use his words and example as spiritual keys to close the hearts of the faithful to the devil and open them to hearing and fulfilling the word of God (cf. Pontificale Romanum, “De ordinatione ostiariorum”).

To this day, the baptism of infants and the rite of acceptance into the catechumenate begin at the church entrance, for all Christians pass through an entranceway, the sacramental portal of baptism, which the Council of Florence (1439) called the “door to the spiritual life” (DS 1314), and which the Code of Canon Law still calls the “door to the sacraments” (can. 849).

The door which is baptism, however, derives its force and meaning from the One who said of himself: “I am the gate. Whoever enters through me will be saved, and will come in and go out and find pasture” (Jn 10:9). Because of baptism, we are now able to enter through Christ, the Good Shepherd, into the pastures of divine life.

In the same passage, though, Jesus also says that “whoever enters through the gate is the shepherd of the sheep. The gatekeeper opens it for him, and the sheep hear his voice, as he calls his own sheep by name and leads them out” (Jn 10:2-3). In this verse he is referring to himself not as the gate but as the One who has passed through a gate and leads us along with him. Here the gate means our access to the eternal dwelling of the Father. Jesus passed through this gate at the moment of his own Passover when he offered himself as the true paschal lamb, as the Letter to the Hebrews says: “When Christ came as high priest of the good things that have come to be, passing through the greater and more perfect tabernacle not made by hands, that is, not belonging to this creation, he entered once for all into the sanctuary, not with the blood of goats and calves but with his own blood, thus obtaining eternal redemption” (Heb 9:11-12).

Living the Christian faith, then, is essentially a rite of passage: a passing over from the old life of slavery to sin and death to the new life of divine adoption, through the One who is our gate and shepherd and in whom we can “confidently approach the throne of grace to receive mercy” (Heb 4:16). The moments of that passage are fittingly expressed by the metaphor of a door: as we close the door on one chapter of our life, we open it to a new one. Crossing that kind of threshold, though, also requires the opening of an interior door, the door of our hearts, so that we may welcome the One who “stands at the door and knocks” (cf. Rev 3:20). Through baptism, the “door to the spiritual life,” we open the door of our heart to that Divine Door through whom we make a fresh start and enter the new life of grace and mercy.

The final transition will be our passage from this life into the eternal kingdom. Just as the gates of Paradise were closed to the human race after the sin of our first parents (Gn 3:23-24), it is Christ who “has unlocked the gates of heaven” (Preface IV of the Sundays in Ordinary Time), so that “we, his members, might be confident of following where he, our Head and Founder, has gone before” (Preface I of the Ascension of the Lord). After we have opened the door of our hearts to him who is the Door and by whose grace we have passed through the door of baptism into a new life, we can then follow our Good Shepherd through the final gateway that leads to the verdant pastures of eternal happiness.

Holy Years and Holy Doors

As the year 1300 approached, Pope Boniface VIII saw the turn of a new century as the opportunity to make the gifts of grace and mercy more abundantly available to the faithful. What to call this special year of mercy? There was perhaps no better term than “jubilee.” According to the Book of Leviticus, after seven weeks of years (i.e., forty-nine years) the ram’s horn would sound throughout the land, proclaiming a special year when debts would be pardoned, slaves freed, and property returned to its original owners: “You shall treat this fiftieth year as sacred. You shall proclaim liberty in the land for all its inhabitants” (Lv 25:10a). The whole people were to “feel the wind that is the trumpet of liberty blow over the land of the living,” as Chesterton put it. From the Hebrew word for ram’s horn (yôbēl) comes our English word “jubilee,” and the idea of a universal restoration to the way things should be in God’s sight became the theme of the Christian Jubilee, when the Lord’s mercy would be joyously celebrated through the sacramental grace of Penance, the lifting of censures, the granting of indulgences, and pilgrimages to the tombs of the Apostles Peter and Paul.

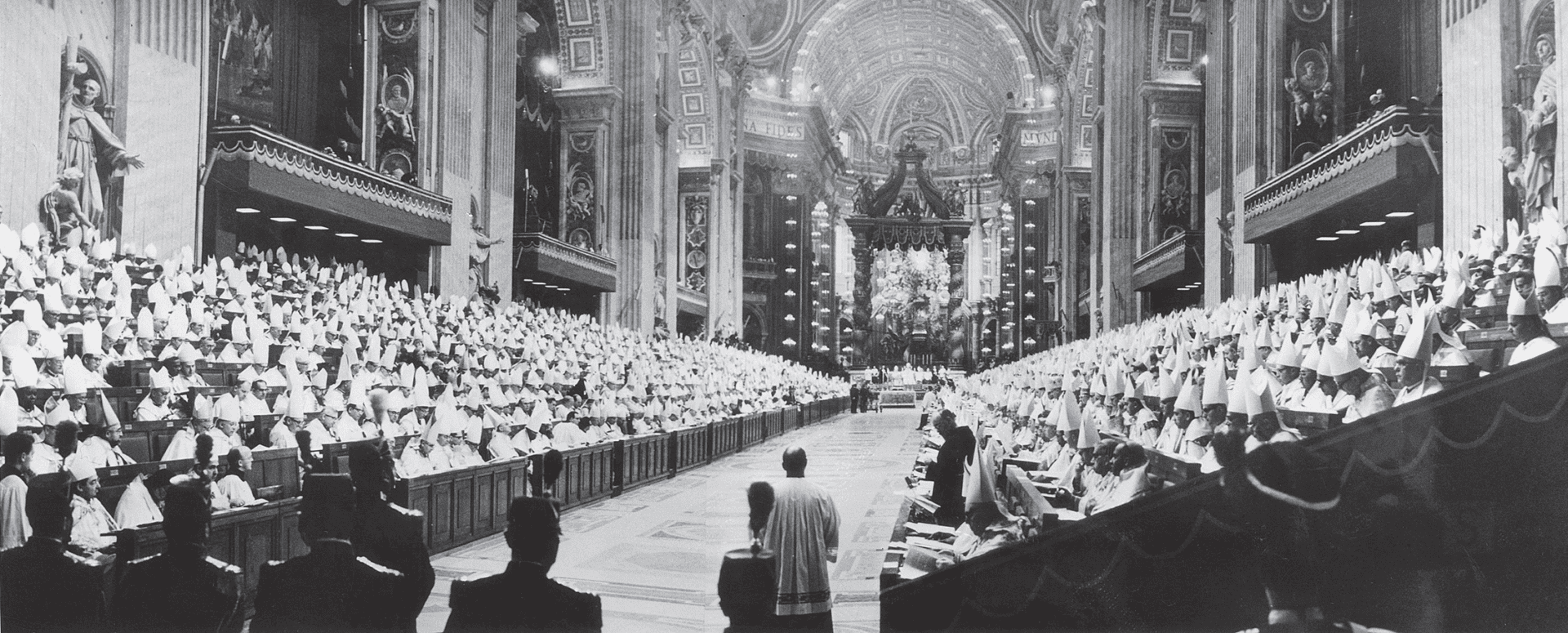

In Pope Boniface’s original plan, a Jubilee Year was to be celebrated at the turn of each new century. However, it soon became apparent that the ninetynine- year span between Holy Years would exceed most lifetimes and thus many people would be deprived of the Jubilee graces, so Pope Clement VI decreed in 1342 that Jubilees would be celebrated every fifty years, as in Leviticus, starting with the Holy Year of 1350. Pope Paul II would later increase the frequency to every twentyfive years, beginning in 1475. That has remained the pattern down to our time, with some notable additions: the Extraordinary Holy Year of 1933, to celebrate the 1,900th anniversary of human redemption, and the fiftieth anniversary of that Holy Year in 1983. The Holy Year that opens this December 8 is also The Holy Door and the Year of Mercy an Extraordinary Jubilee.

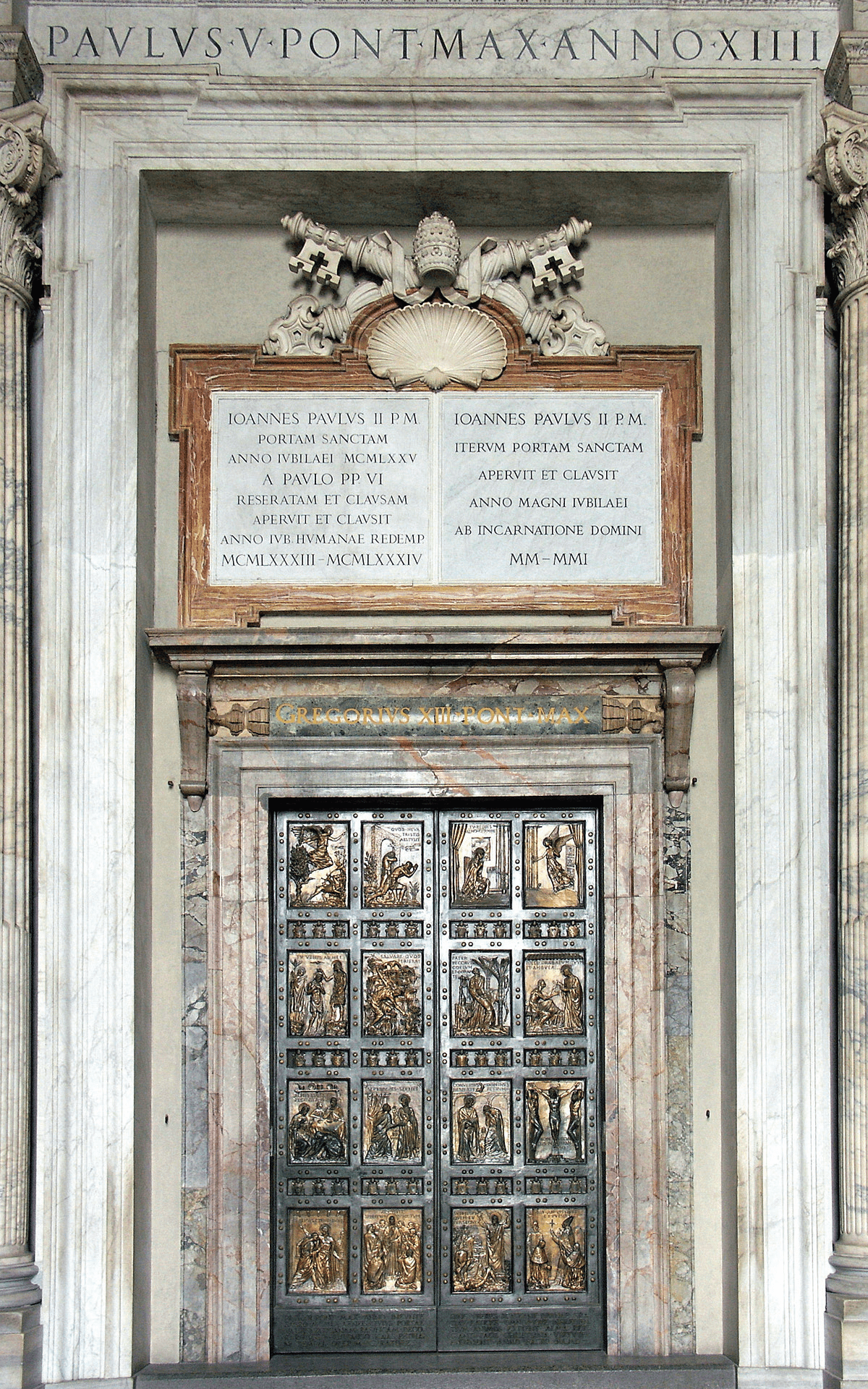

It is not entirely clear when the granting of the Holy Year indulgence first became associated with passing through a designated “holy door,” but it certainly seems to have been established by the middle of the 15th century, about 150 years or so after the first Holy Year of 1300. From what has been said above it is easy to see the rich symbolism of crossing the threshold of a doorway to mark a new life, a fresh start, the transition to a renewed relationship with God. Liturgical celebrations of the Holy Year apply Psalm 117 [118]:19-20 to the opening of the Holy Door: “Open the gates of righteousness; I will enter and thank the Lord. This is the Lord’s own gate, through it the righteous enter.” These verses originally referred to entering the Jerusalem temple, which was permitted only to the righteous Jew, but since Christ in his risen body has become the new temple (Jn 2:19-22), and our destiny is the new and eternal Jerusalem (Rv 21:10-27), the fuller Christian meaning of this text can be seen in all its spiritual and eschatological significance.

Pope Francis has invited the entire Church this coming year to celebrate the gift of divine mercy and to make its spiritual fruits even more available to the faithful. An essential ritual element of this celebration will be passing through a Holy Door to symbolize our desire in Christ to leave behind any affection for sin and to open our hearts to his gift of mercy and reconciliation: “On that day, the Holy Door will become a Door of Mercy through which anyone who enters will experience the love of God who consoles, pardons, and instills hope” (Pope Francis, Apostolic Letter Misericordiae vultus, 3). The Holy Father has also stipulated that every cathedral should also have a Holy Door, which is to be opened on December 13, the Third Sunday of Advent, after he has opened the Holy Door in St. Peter’s Basilica on December 8 to inaugurate the Year of Mercy. In this way any member of the faithful can obtain the Jubilee indulgence without having to make a pilgrimage to one of the papal basilicas in Rome.

In conclusion, this coming year is an opportunity to reflect on the deep spiritual significance of the Holy Door as a symbol of God’s mercy, taking to heart what St. John Paul II said when he opened the Holy Door for the Great Jubilee of the Year 2000: “You, O Christ, the Son of the living God, be for us the Door! Be for us the true Door, symbolized by the door which on this Night we have solemnly opened! Be for us the Door which leads us into the mystery of the Father. Grant that no one may remain outside his embrace of mercy and peace!” (Homily, December 24, 1999).

Msgr. Robert J. Dempsey, a native Chicagoan, holds an M.A. degree in philosophy from Loyola University (Chicago), an S.T.B. from the Pontifical Gregorian University, an S.T.L. from the University of St. Mary of the Lake, and an S.T.D. from the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross (Rome). Ordained a priest by Pope John Paul II in 1980, he worked as an associate pastor in three parishes. From 1991 to 2001 he was editor of the English edition of L’Osservatore Romano, the Vatican’s newspaper. He is currently pastor of St. Philip the Apostle Parish in Northfield, IL., and serves as a member of the Presbyteral Council, the College of Consultors, the Archdiocesan Bioethics Commission, and as a visiting lecturer at the Liturgical Institute in Mundelein.