Online Edition

August 2014

Vol. XX, No. 5

Clergy Seating through the Centuries

Part II — The Enclosed Choir in the Medieval Cathedrals and Abbeys

by Daniel DeGreve

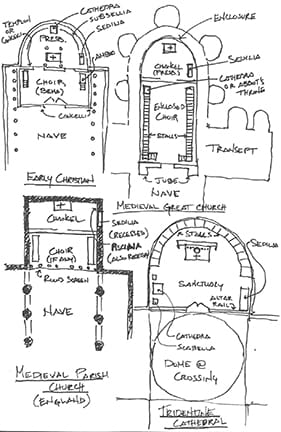

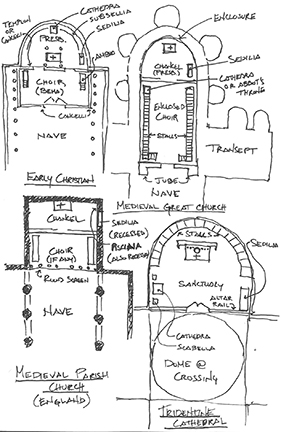

The above sketch shows a comparison of clergy seating layouts from various historical periods before Vatican II (sketch by Daniel DeGreve ©2014)

The ecclesial institutions of the medieval Church are sometimes maligned by contemporary-minded liturgists and church historians as having been exaggeratedly clerical in nature. Perhaps the most obvious artifact of this so-called clericalism is the fully enclosed choir or chancel, a relative few of which still exist in some of the celebrated cathedrals, abbeys, and collegiate churches of Europe that render the effect of a church within a church.

Such choirs are partitioned by monumental, richly carved stalls on either side in the antiphonal arrangement and, sometimes, along the short end opposite the altar to form a U-shape, and by the occasional surviving choir screen — which according to its particular function and provenance may go by the term pulpitum, jube, lettner, trascoro, tramezzo, or rood screen.

Yet, for a proper and accurate understanding of the transformation of the early basilica bema-choir and presbyterium into the lengthy eastern limbs of the late medieval great churches, it is helpful to keep in mind that as the liturgy evolved through the centuries while its essential form and purpose were maintained, so too did the accommodations that served it.

One of the pivotal contributions was made by the eighth-century Frankish bishop Saint Chrodegang of Metz, who developed a rule of communal life for the priests of his cathedral based on Augustine’s earlier rules for the same, and, in so doing, laid the foundation for the systematic erection of cathedral chapters during the Carolingian era — courtesy of the Council of Aachen in 816. The principal duty of the canon priests who belonged to these chapters was the daily celebration of the Office in the cathedral. Although the life of a canon was distinct from that of a monk, the introduction of canonical chapters did advance a more monastic paradigm for the layout of cathedrals; although some, like Canterbury in England and most of those in the British Isles, had been monastic from their foundation. Similarly, the emergence of chapters attached to non-cathedral churches gave rise to the quasi-monastic collegiate churches of ascendant European towns and cities, especially in those of the Low Countries.

Another critical development that propelled the need for a compartmentalized choir was the growing popularity of pilgrimage during the Middle Ages. As the veneration of relics became more widespread throughout Europe, the large influxes of pilgrims crowding into shrine churches gave rise to choirs that provided more privacy for the monks or canons attached to them as they celebrated the Office. While privacy and protection from irreverence fed the pragmatic impetus for this spatial detachment from the nave, there was a corresponding liturgical symbology that tended toward the increased enhancement of the Solomonic attributes of a church as the Christian temple.

The invention of choir stalls was a gradual process that grew out of the use of subsellia and sedilia. The Rule of St. Chrodegang refers to the standing posture of the singers and other lesser members of the community, and, as late as the eleventh century, Saint Peter Damien wrote against seating: “Contra sedentes in choro.”1 However, this attitude weakened as choir service became longer and more elaborate. Sometimes the use of T-shaped crutches (reclintoria) by the elderly or infirm was permitted, and even the plan of St. Gall included choir seats with backs (formae or formulae), which were likely moveable appointments. However, by the eleventh century, fixed seats divided only by arms — stalli — had come into existence, and from that time they took on an increasingly architectural form that defined the choir space even more distinctly than it had been previously.2

By the fifteenth century, wooden choir stalls in universal use had high, richly paneled backs, and were fitted with elaborately carved seats, dividers, and canopies. Some of the finest figural ornament can be found on the misericords, customary brackets underneath the hinged seats that, when the seats were turned up, provided relief to standing clergy who were able to lean against them. In Italy, highly detailed narrative scenes and figural decoration were executed on the backs of stalls with the use of intarsia, a method of inlay wood design.

While the senior clergy — whether they be monks, friars, or canons — occupied the high-backed stalls along the periphery of the choir enclosure, one or more rows of low-backed stalls or choir pews were placed on either side in front of them. These were used by chaplains, brothers, and lay clerks, including vicars choral, who were professional male singers introduced in the late Middle Ages for the purpose of singing the more complicated polyphonic liturgical music. Each successive row was placed a step higher than the one in front of it, and was equipped with a book ledge and kneelers supported by the backs of the preceding row. The front row of seats were sometimes provided with a continuous modesty panel topped by a ledge rail for the same purpose. The end panels of these rails and seat dividers became situations for embellishment that came to include carved floral finials and the like.

The development of the choir stall was accompanied by the prevailing tendency to locate the bishop’s cathedra or abbot’s throne along the Gospel side of the choir rather than behind the altar in the apse, which O’Connell places as early as the ninth or tenth centuries on the Continent, and no later than the twelfth in England.3 In some places, such as Canterbury and Norwich, the ancient ceremonial cathedra remains to this day on its dais at the head of the apse, although a secondary bishop’s seat, conforming to a stall, was added to the medieval choir, which became the one normally used by prelates during choir service. Clerical offices were distinguished by the articulation of their respective stalls and their locational relationship to each other. The bishop’s canopy was generally the largest and most elaborate, followed by that of the dean and/or provost. In some cases, a lay-person, generally a monarch or noble beneficiary, might also have an honorary stall for his use during state visits.

The presbyteries of cathedrals and abbeys came to be positioned in front of the high altar as they likely already had been all along in the much smaller ecclesiae rusticanae, or parish churches. Yet, the distinction between the choir and presbyterium, or chancel, remained.

It is important to note that choir stalls were typically used by the clergy during choir service, not by the celebrant and his assistants during Mass. The presbyterium was still set beyond the choir and its stalls, and occupied the area about the altar, generally raised a step above the choir and railed off from it. The celebrant of the Mass and his assisting ministers would have sat in the presbyterium on seats, which will be described in greater detail in the following section. The essential traits of this choir-presbyterium sanctuary arrangement can still be appreciated in some of the great Gothic cathedral choirs of Europe, such as at Amiens and Auch in France, and has been extensively retained within the Anglican tradition from large cathedrals to modest parish churches.

As mentioned above, in the great churches, the choir became more detached from the nave through monumental partitions, as can still be seen throughout England, Spain, Belgium, and parts of Germany, and through dramatic transitions of floor level, which is idiomatic of northern Italy. The location of an altar in front of the partitioned or elevated choir for the analogous celebration of the Mass in the more immediate presence of the laity became common in cathedrals and collegiate churches. Such altar arrangements still can be appreciated in various locales throughout Europe, such as in the monastic church of San Miniato al Monte in Florence and the former cathedral of Magdeburg. These altars do not seem to have been equipped with any fixed clergy seating that has survived in modern times, but probably included moveable wooden sedilia.

Parish churches, which became identified as such by the eleventh century, functioned primarily on behalf of the laity, so that the choir, if included, was a relatively short space with only a few stalls. Nevertheless, the Office was dutifully sung by a small community of priests, or even by some individual rectors, and the choir/ chancel was usually separated by a screen not unlike cathedrals and abbeys. Squints, which were apertures cut through the thicknesses of walls, permitted views of the high altar where heavier screens were used, and allowed the laity to venerate the Host when it was elevated.4 The rood screens and choir stalls of these village churches can still be appreciated, such as those of the Church of St. Mary in Westwell, England and a host of late Gothic churches in Swabia and the Black Forest in Germany.5

Late Medieval and Tridentine Sedilia

Briefly mentioned in Part I of this article, sedilia (plural of sedile) were benches composed of multiple seats, usually three or sometimes five in number, which corresponded to the number of celebrating and assisting ministers during Mass. It was customary for the celebration of Mass in its solemn high form to include either two deacons or a deacon and subdeacon to assist the celebrant. The primitive sedilia of the first millennium was an undivided wooden or stone bench, usually fixed and always placed near the altar, and probably without much of a back and certainly no arms, so as not to compete with a cathedra.

A couple of the earliest surviving examples are from Sant Climent in Taüll, Spain (1200), and the monastery in Gradefes, also in Spain.6 As previously described, the sedilia came into common use during the Middle Ages, from cathedrals to simple parish churches, especially as the apsidal synthronon of the early basilicas tended toward eventual obsolescence in favor of an altar visually engaged to the apse wall in its stead.

As Christendom “cast off its old garments to cover itself in a white vesture of churches,” the design of sedilia took an innovatively architectural turn. By the second half of the twelfth century, sedilia began to be incorporated, quite literally, within the masonry structure of the Epistle side (pictured below this paragraph) wall of the presbyteries. Recessed and articulated with one or more arches, the pattern of wall sedilia often followed that of the blind arcading that lent visual relief to the heavy walls, and were complemented by the adjacent piscina niche, where the ritual ablution of the Eucharistic vessels was performed. Often the stone seats of recessed sedilia were separated by small columns or mullions supporting their capping arches, and were not uncommonly placed at a stepped profile analogous to the floor elevations — the one closest to the altar raised at the highest level and being reserved for the celebrant. Otherwise, the seats were placed in alignment to each other, as seen in the ruins of Ardfert Cathedral in County Kerry, Ireland. In village parish churches, only a single sedile recessed in the wall might be provided. In other cases, a single stone bench was made long enough for two or three persons. Whereas brightly painted, stenciled, or glazed tile designs often decorated the back surfaces of recessed sedilia, small stained-glass windows may also punctuate them, as can be found in France and England, such as at Dorchester Abbey in Oxfordshire. Small curtains sometimes were used at the back to keep away cold drafts from their occupants, and were color-coordinated with the vestments in liturgical season and occasion. As Gothic architecture flowered with increasing ornamental elegance, especially after the thirteenth century, the ceiling surfaces of some recessed sedilia became vaulted compartments detailed with delicate ribs and bosses, and intricately executed stone canopies — not unlike those of the wooden choir stalls.

At the Basilica of the Sacred Heart at the University of Notre Dame, the presider’s and assisants’ chairs are canted at an angle on the traditional Epistle side of the Sanctuary, a common solution seen today. (source:http://www.ndneighborhood.com/)

Recessed wall sedilia were employed throughout European locales, especially in the North and in Spain, with the notable exception of Italy, where the articulation of wall mass tended to be more planar than sculptural in design. There, freestanding sedilia with low backs were placed near the Epistle wall. The low back distinguished the sedilia from the cathedra, and also allowed for the long vestments donned at the altar. As a Classical architectural grammar of Italian persuasion gradually spread northward beyond the Alps, the sedilia tended to revert to a piece of wood furniture, even in locales where the recessed wall sedilia had been previously favored. Similarly, faldstools continued to be used by prelates when not officiating in their own cathedral.

The spirit of the Counter Reformation and the Council of Trent brought about an attitudinal shift regarding the size and prominence formerly assigned the choir and chancel. Improving visibility of the high altar and the ritual of the Mass for the edification of the laity was the overriding priority and impetus for this transformation, and it was accompanied by a gradual diminishment of obligation to the communal profession of the Office by canons and the secular clergy in their churches.

Although Saint Charles Borromeo did not offer a preference for the position of choir stalls relative to the high altar in his book of instructions to the priests of his archdiocese regarding church layout, the second half of the sixteenth century onward witnessed the reordering of choirs throughout Italy. The Italian solution, as it might be called, was to locate the choir stalls in the chancel completely behind the high altar in the curvature of the apse, as at the cathedral of Piacenza, or to allow them to surround the high altar, as at Borromeo’s own cathedral of Milan, where they begin well in front of the high altar and continue behind it.

Even in monastic churches, such as Andrea Palladio’s masterpiece of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice, the Benedictine choir with its wooden stalls was placed in the apse behind the high altar, and visually partitioned by a handsome trabeated organ case. One might see this ‘retro-choir’ (not in the British sense), whereby the function of the patristic bema-type choir was now wed to the apsidal presbyterium, as a natural answer in a tradition-laden part of Christendom that had tended to cling to ancient forms and semiotics all along. It is even defensible that such arrangements had existed prior to the Counter Reformation, as has been elucidated in the research of Donal Cooper on the function of double-sided altarpieces in pre-Tridentine Franciscan choir enclosures in Umbria.7

High altars in Italy were moved forward to accommodate relocated choirs in pre-existing churches. Frequently, new large canvas altarpieces were still applied to the apse wall, although the altars themselves now stood some distance in front of them, as at the cathedral of Cremona. The cathedra and its associated faldstools for lesser prelates might be kept on the Gospel side of the shortened chancel space in front of the altar, placed at one end of the horseshoe-shaped apsidal choir, or in the midst of the choir stalls, as at Spoleto and Orvieto. Classical taste favored the use of brocaded testers over the cathedra to bolster its visual prominence when placed on the Gospel side, just as the wooden Gothic canopies of northern Europe had done. The wooden bench-like sedilia for the celebrant and his assistants remained essentially unchanged in form although some with seat dividers do exist from the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Additionally, wooden stools known as scabella were provided for lesser ministers, such as acolytes and other servers, and were placed along the side walls of the sanctuary in proximity to the sedilia and high altar.

The Jesuit mother church of Il Gesu in Rome has been held up by historians as a poster-image of the ideal Tridentine church layout. In describing it, we may temporarily dispense with the terms choir and chancel, and refer to the sanctuary instead. The sanctuary of Il Gesu is relatively shallow and is separated only by a step or two and a low altar rail, which is a dematerialized version of the ancient cancelli. The high altar and tabernacle are unencumbered by choir stalls. Across Catholic Christendom, shallower sanctuaries and clearer sightlines of high altars ubiquitously prevailed in Tridentine layouts.

The Second Vatican Council and the Presider’s Chair

In 1955, seven years before the solemn opening of the Council, the Reverend J.B. O’Connell wrote the following on the sedilia in his book Church Building and Furnishing: The Church’s Way:

For the sacred ministers (celebrant, deacon and subdeacon, and sometimes an assistant priest) … the only seat appointed by the rubrics is a movable bench, long enough to seat three persons comfortably, with no divisions (making any distinction between its three occupants), without arms and un-canopied… This bench must be placed on the floor, not on a platform so that it is approached by steps. It may have a low back, over which the vestments of the ministers can hang, when they sit, to avoid crushing them. By a series of decrees, [the Sacred Congregation of Rites] has forbidden the use of armchairs, or separate chairs of a domestic pattern, by the sacred ministers, since the former are reserved for higher prelates, and the latter are unsuitable for liturgical use… The bench is placed, normally, on the Epistle side of the chancel facing the side steps of the high altar.8

O’Connell goes on to describe the tradition of covering the sedilia with a color-coordinated non-silk cloth according to the day, ritual, and/or Office. Yet the centuries-old side placement of the sedilia described above was generally discarded during the dramatic changes that were made according to the spirit of Vatican II less than 20 or 30 years after this preceding passage was published. Sacrosanctum Concilium never mandated any formula for seating, but the revisions to the General Instruction of the Roman Missal that were released following the Council did offer the ancient Roman model of the apsidal cathedra as an option for the celebrant.

The option of celebrating the Mass versus populi, or toward the people, necessitated the provision of freestanding altars without the visual impediments of retables, tall candlesticks, and altar crucifixes, which in turn freed up the space behind them for the cathedra or presider’s chair, as well as chairs of assisting ministers, including members of the newly re-established diaconate. The result, especially in cathedrals, was an arrangement not unlike the synthronon of old. While the sedilia itself was not specifically forbidden by the rubrics, its association with what became the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite and its antiphonal (sideways) orientation made it seem antiquated and unconducive to the engagement of the laity’s active participation. Hence, many bishops, pastors, and liturgists saw to their removal, relocation, repurposing, or outright disposal.

Practically speaking, and not necessarily in sight of the tradition thus covered here, there are occasions when placing the clergy seating behind the altar may be a viable programmatic and aesthetic response to a design problem, particularly when dealing with limited side space in a small chancel or seating in-the-round. Generally, the best way to accomplish this is to place the seats off to the side and at a cant (angle), so as to not obstruct the visual axis between the altar and the tabernacle.

From an archaeological perspective, however, it is interesting to note that there seems to be a persisting sense amongst many modern liturgists that the presider’s chair — versus populi — is representative of a return to the liturgical patrimony of the early Church, or at least its spirit. In the latest edition of the General Instruction of the Roman Missal, the versus populi orientation of clergy seating continues to be viewed as a more compatible position for leading the assembly in prayer than the antiphonal orientation, which somewhat obscured the priest’s face from the laity, but fashioned an essentially uniform prayerful posture of celebrant and congregation toward the altar of Christ’s Sacrifice. While seating of a domestic type — once prohibited according to the Sacred Congregation of Rites — is seen just about everywhere, and though some may think questioning its use is an insignificant matter, it will be fitting to close with these words taken from Pope Pius XII’s encyclical Mediator Dei:

62. …But it is neither wise nor laudable to reduce everything to antiquity by every possible device. Thus, to cite some instances, one would be straying from the straight path were he to wish the altar restored to its primitive table form; were he to want black excluded as a color for the liturgical vestments; were he to forbid the use of sacred images and statues in churches; were he to order the crucifix so designed that the divine Redeemer’s body shows no trace of His cruel sufferings; and lastly were he to disdain and reject polyphonic music or singing in parts, even where it conforms to regulations issued by the Holy See.

63. …Just as obviously unwise and mistaken is the zeal of one who in matters liturgical would go back to the rites and usage of antiquity, discarding the new patterns introduced by disposition of divine Providence to meet the changes of circumstances and situation.9

If ever there should be a movement to restore the sedilia to common use — and its traditional antiphonal position, which the author dares to say is the more critical of the two related issues — the defenders of the versus-populi poised presider’s chair may readily invoke the preceding passage as an injunction for dispelling reversion to a previous form and arrangement.

Yet, any examination of the Church’s heritage will demonstrate that divine Providence works through timeless means and methods — even occasional follies.

NOTES:

1. T. Poole. “Choir (Architecture),” The Catholic Encyclopedia. (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908). www.newadvent.org

2. Ibid.

3. J.B. O’Connell. Church Building and Furnishing: The Church’s Way. (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1955), 93-94.

4. John Henry Parker. A Concise Glossary of Architectural Terms. (New York: Crescent Books, 1989), 264-265.

5. Justin E.A. Kroesen. Staging the Liturgy: The Medieval Altarpiece in the Iberian Peninsula. (Leuven, Belgium: Peeters, 2009), 162.

6. Ibid.

7. Donal Cooper. “Franciscan Choir Enclosures and the Function of Double-Sided Altarpieces in Pre-Tridentine Umbria,” Journal of the Warburg & Courtald Institutes. (2001), Vol. 64, 1-54.

8. J.B. O’Connell. Church Building and Furnishing: The Church’s Way. (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1955), 67-69.

9. Pope Pius XII – Mediator Dei. 1947 encyclical.(adoremus.org/MediatorDei.html )

***

Daniel P. DeGreve is an architect with David B. Meleca Architects LLC in Columbus, Ohio. He has contributed articles to both The Adoremus Bulletin and Sacred Architecture Journal. Specializing in traditional ecclesiastical architecture and furnishings in addition to urbanism, Daniel has led the design for several church restoration and renovation projects, including that of his native parish in Ohio. He is presently involved in the design of additions and improvements to an 1837 Greek Revival church, which will incorporate a new clergy sedilia inspired by the patterns of Asher Benjamin. Daniel holds a Master of Architectural Design & Urbanism from the University of Notre Dame (2009), and a Bachelor of Architecture from the University of Cincinnati (2002).

Amiens Cathedral painting by Charles Wild showing a solemn liturgy being celebrated at the high altar and choir around 1826. Note the conons in their stalls, the bishop at his cathedra on the left, and the cantors in the center foreground. (Source: http://www.yeodoug.com/)

The Choir of Albi Cathedral in southern France, showing the Gothic ornament of the stalls and their enclosure, including the great jube with its Calvary rood. (Source: Wikimedia)

The twelfth-century Norman recessed sedilia in the Church of St. Mary de Castro in Leicester, England is one of the earliest surviving of its kind. Note the slightly stepped profile of each seat. (Photo: Father Lawrence Lew, OP ©2014)

The fifteenth-century sedilia of Dorchester Abbey (Oxfordshire) in use by the celebrant and assiting ministers during the Roman Catholic Requiem Mass for Dr. Mary Berry in 2008. (Photo: Father Lawrence Lew, OP ©2008)

Seton Parish Church in Pickerington, OH, features an unusal placement of the presider’s and deacon’s chairs on the raised island behind and separate from the altar platform. (Photo: Daniel DeGreve ©2014)

The presider’s chair is placed behind the altar in the Chiesa di Brembo a Dalmine in Bergamo, Italy. (Photo: http://asthought.polimi-cooperation.org/)

The antiphonal placement of the presider’s and assistants’ chairs in the chancel of St. Patrick Church in Columbus, Ohio offers a more traditional orientation for liturgical prayers. (Photo: Daniel DeGreve ©2014

Adoremus, Society for the Renewal of the Sacred Liturgy

*