Online Edition

June-July 2014

Vol. XX, No. 4

Clergy Seating Through the Centuries:

The Origin of the Presider’s Chair

Part I

by Daniel DeGreve

In the years since the Second Vatican Council, an increased emphasis on flexibility and the direct face-to-face contact of clergy relative to the laity during the celebration of the liturgy have spawned a variety of postural trends for the seating of the clergy. Some of these are derived from historical models, while others are essentially modern innovations.

This variety has had a marked effect on the relationship between sacred orientation and liturgical prayer. The variety has also had a considerable impact on the architectural configuration of the sanctuary, both in new churches and renovated ones.

A historical survey highlighting clergy seating through the centuries may illustrate that — as with so many aspects of Catholic practice — there are numerous arrangements that have been employed, and the proper use of these has been contingent on the context of the given ecclesial typology, whether the church be great or small.

Before we begin such a survey, it is necessary to refer to the Church’s present rubrics, which specify how the clergy and other sacred ministers in the sanctuary are to be accommodated. Chapter V of the General Instruction of the Roman Missal states the following:

310. The chair of the priest celebrant must signify his function of presiding over the gathering and of directing the prayer. Thus the more suitable place for the chair is facing the people at the head of the sanctuary, unless the design of the building or other features prevent this: as, for example, if on account of too great a distance, communication between the priest and the congregation would be difficult, or if the tabernacle were to be positioned in the center behind the altar… Likewise, seats should be arranged in the sanctuary for concelebrating priests as well as for priests who are present at the celebration in choir dress but without concelebrating… The seat for the deacon should be placed near that of the celebrant. For the other ministers seats should be arranged so that they are clearly distinguishable from seats for the clergy and so that the ministers are easily able to carry out the function entrusted to them.

The Patristic & Early Medieval Church

Initially, the bishop celebrated the sacred liturgy for the local Christian community with the assistance of his priests, the presbyters. According to the Syrian Didascalia Apostolorum, a fourth-century text that is derived from an earlier Greek one of the early third century:

For thus it is required that the presbyters shall sit in the eastern part of the house with the bishops…1

From the early centuries onward, the cathedra (bishop’s chair) itself served as an important symbol of his teaching and governing authority. The earliest cathedrae were simple wooden chairs; in rare cases, they may have been made of stone.

When the typology of the Roman basilica was adopted on a monumental scale for the purpose of Christian worship in the West, the bishop’s cathedra was generally situated in the apse in an analogous manner to the faldstool, the curial chair of the civil magistrate who administered justice from the tribune of the secular basilica.

On either side of the cathedra and conforming to the curved wall of the semi-circular apse were fixed benches, known as subsellia, for the presbyters; these were usually made of stone, and were derived from the lower seats accorded lesser officials of the Roman courts.2 This arrangement is called a synthronon, a Greek word meaning communal seat, and it was used in both the Western and Eastern traditions. The synthronon formed the part of the church called the presbyterium (or presbytery), a word that is still used today in reference to the area within the sanctuaries of large churches, such as cathedrals, where the clergy, also known collectively by the same term, are accommodated.

The altar was placed in front of the synthronon, either within the apse or at its entrance near the triumphal arch. It was typically crowned by a canopy known as a ciborium, which was veiled with curtains during the celebration of the Eucharistic canon.

A colonnaded structure known as a templon often extended the breadth of the space in front of the presbytery, and, likewise, had curtains that were drawn during the most solemn parts of the Eucharist. This appointment was especially used in those parts of the West that retained close ties with the East, such as the Byzantine cities of Italy. A remarkably late, intact, and unique example of an all’antico synthronon with tiered subsellia, raised cathedra, and open templon can be found in the ninth-century portion of the cathedral of Torcello, near Venice.

Because it was raised above the floor level of the nave and aisles, the apsidal presbyterium or tribune is also sometimes referred to as the bema, a term derived from the Hebrew bimah that refers to the raised platform customarily located in the middle of synagogues where readings from the Torah were proclaimed and prayers recited in the midst of the assembly.

In the cases of the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore and Santa Maria in Trastevere in Rome, the bema did coincide with the presbyterium; although in the latter example, the Scriptures were read from an ambo in the nave. However, the association is more often understood in Western Christian parlance as an architecturally distinct space within the nave, analogous to the role and form of its Jewish antecedent, from where the Scriptures were proclaimed and psalmody chanted.

A single elevated ambo initially was employed for the readings, but, in time, it was replaced by two ambones — one for the Epistle and one for the Gospel. Meanwhile, an ensemble of lesser clergy — probably deacons and subdeacons — was grouped around these ambones on a slightly raised and partitioned platform for the chanting of the psalmody.

In the West the bema became known as the choir, the terminological usage of which has been attributed to Saint Isidore of Seville (560-636) and Honorius of Autun (1100s), who coined the term as a derivative of the Latin corona in reference to the circle of clergy and singers surrounding the altar.3

The singers stood facing each other during the entire liturgy, lined along the side cancelli, the low walls demarcating this part of the church as distinct from the surrounding nave and adjacent presbyterium. Hence the word chancel, a term that is often interchanged with choir, presbyterium, and sanctuary. Sometimes the cancelli were continued around the presbyterium if it projected into the nave, such as at San Clemente and Santa Sabina all’Aventino in Rome. Santa Maria in Cosmedin, also in Rome, retains a similar arrangement with a templon between the choir and presbyterium.

The cathedra itself became an ornate high-backed chair with arms — a throne, in effect, made of stone, precious metals, or ivory. One of the earliest surviving specimens of this type is the lavishly carved ivory throne in Ravenna, Italy that is associated with the sixth-century Bishop Maximianus.

Although it was customary for the bishop to deliver his homily from his cathedra in the first centuries of the Church, with the transfer of the liturgy to the basilicas erected from the period of Constantine onward, this practice would seem to have become difficult in the greater churches because of the distances and visual obstructions involved. One might question, however, whether this seeming impracticability owes more to modern sensibility than to historical actuality.

Nevertheless, the use of a portable cathedra or a faldstool that could be set up near the altar for the purpose of preaching has been suggested as a means used for overcoming the postural isolation in the apse. Eventually, the conventional placement of the cathedra was transferred to the Gospel (left) side of the choir. The Reverend J.B. O’Connell, in his book Church Building and Furnishing, offers a time as late as the ninth or tenth centuries for this innovation.4

Seating for the Laity

To understand the significance of the accommodations that were provided for the clergy within an early basilica church, it is necessary to comment on the position of the laity.

At first glance, it may seem reasonable that the congregation occupied the spacious nave in front of the choir and presbyterium. In his Turning Towards the Lord, however, Father Uwe Lang presents the theory of the German liturgist Monsignor Klaus Gamber (1919-1989) that the laity took their places in the side aisles, reserving the nave for liturgical actions, such as the processional entry of the celebrant and his assistants.5 Whether or not the nave was completely restricted to the laity during the Eucharistic liturgy in the large basilicas can be reasonably questioned, as Father Lang suggests, but the multiplicity of side aisles would seem to support the idea that these lesser areas were also occupied and offered a convenient means for maintaining the separation of men and women — as were the so-called women’s galleries or matronei over the aisles. The relevant point to be made, in any case, is that the direct face-to-face contact between the celebrant and the congregation was, in all likelihood, not only unimportant, but, in all probability, virtually impossible during much of the ritual involved in the fourth-century and early medieval liturgy.

As the liturgy evolved, so did the customs associated with its spatial definition and ritual accommodation, although the modern understanding of this process is rather fragmented because of the scant evidence that survives. The rule of Saint Augustine of Hippo for his cathedral clergy and the nascent institution of Benedictine monasticism fostered a greater concentration on the contemplative life centered on the Liturgy and the Divine Office; consequently among the subscribing clergy, the choir became larger and increasingly defined as the centuries progressed. Abbots of monasteries, like bishops, were seated on thrones that were typically placed at the head of the apse in an analogous manner to those of bishops, flanked on either side by the priests of the community.

Lesser members of the community would have taken their place in the choir in front of the altar. The monastic church plan was a paradigmatic framework that witnessed a dynamic evolution around the ninth century, and had a profound bearing on other related ecclesial typologies.

In addition to the smaller churches and oratories frequently attached to early cathedrals and abbeys, the situations of which still can be appreciated in places like Bologna and Verona in Italy, there also were secondary churches in both the towns and countryside that ministered to local populations precursory to the role of the later, territorially defined “parish church.”

For instance, the town of Grado near Venice has two sixth-century basilicas that were built by the orders of the local patriarch, and the lesser of the two contains a synthronon with an episcopal seat even though the greater church was the actual cathedral.

The layouts of these lesser churches typically were based on those of larger basilicas to a great extent, but a “presider’s chair” situated behind the altar facing toward the congregation would have been unlikely unless it was, in fact, an episcopal seat for the exclusive use of the bishop, as at Grado, or possibly the faldstool of an archpriest of an important titulus (titlechurch) directly tied to the bishop, as was the case in Rome.

The priest celebrant in a rural churches (ecclesiae rusticanae), although initially tied to the cathedral, would have taken his place near the altar on a simple wooden or stone bench with several seats known as sedilia.6

Sedilia may have been either freestanding or engaged to a portion of the cancelli, (chancel) and were located on the Gospel (left) side of the altar in the presbyterium. The sedilia would have accommodated the celebrant and two deacons involved in the ritual of the Mass. A seating position deferential to the bishop and his cathedral presbyterium, rather than analogous to them, seems more plausible when one considers that the cathedral itself played a more direct role in the sacramental life of the entire diocesan community before the establishment of a well-defined parochial system.

For instance, when parochial or “baptismal” churches came into existence, they did not incorporate a separate baptistery building for the placement of the font in imitation of the ancient cathedral arrangement, but placed the font in a far simpler setting near the church entrance, often setting it on the Gospel side of the nave or aisle.

Just as sedilia would have been set up in early cathedrals as the archpriest, with the assistance of lesser priests, began to officiate at the altar in place of the bishop, it seems reasonable that a humbler formula derived from the cathedral would have been used for seating the celebrant clergy who officiated in a rural or secondary church. Unfortunately, few ecclesiae rusticanae of the mid-first millennium survive intact, let alone vestigial traces of their original seating accommodations for the clergy.

This concludes Part I of the examination of the development of clergy seating. In Part II, we will begin with the innovations brought about in the eighth century by Saint Chrodegang of Metz and the Council of Aachen.

Notes:

1 Uwe Michael Lang. Turning Towards the Lord. (San Francisco: Ignatius, 2009), 51.

2 Justin E.A. Kroesen. Staging the Liturgy: The Medieval Altarpiece in the Iberian Peninsula. (Leuven, Belgium: Peeters, 2009), 159-160.

3 T. Poole. “Choir (Architecture),” The Catholic Encyclopedia. (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908). newadvent.org

4 J.B. O’Connell. Church Building and Furnishing: The Church’s Way. (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1955), 93-94.

5 Lang, 83-85.

6 Kroesen, 160.

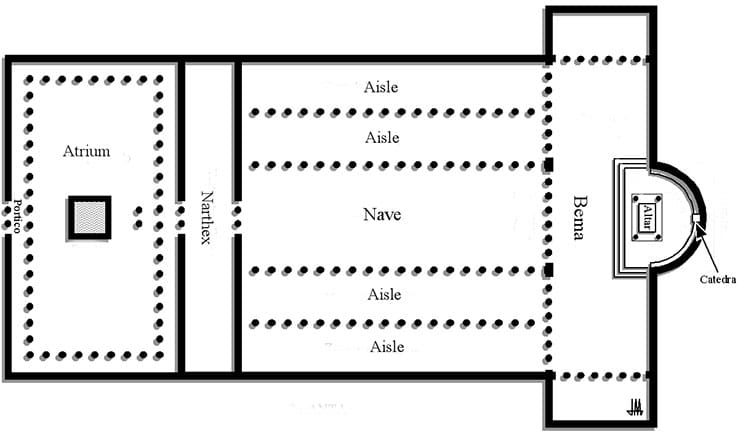

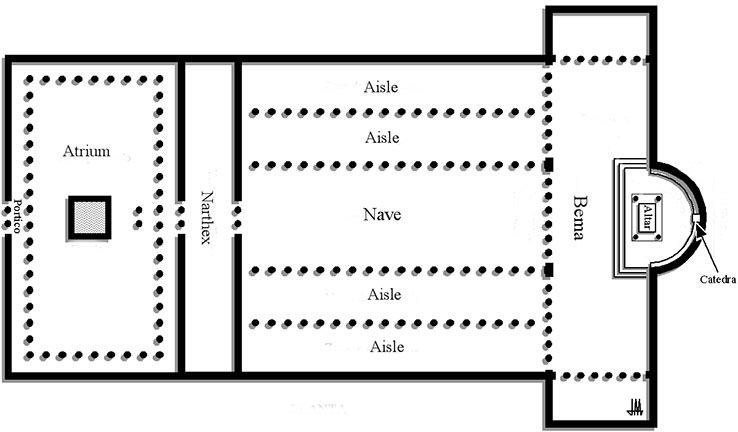

Plan of Old Saint Peter’s basilica, showing atrium (courtyard), narthex (vestibule) central nave with double aisles, and a bema for the clergy extending into a transept. The altar is in the center of the semi-circular apse, and the cathedra (bishop’s chair) is behind the altar, at the head of the apse. (public domain – Locutus Borg, Wikimedia)

Santa Sabina. Dramatically "restored" in the 1930s, the Basilica of Santa Sabina al-l’Aventino in Rome contains a version of the early bema-type choir within the spatial volume of the nave. The presbyterium is elevated above the slightly raised choir, and is provided with another tier of cancelli that symbolically set it off from the choir. While the clergy stalls are of modern provenance, the original synthronon that would have been situated in the apse is no longer extant. Photo credit: Daniel DeGreve

Torcello — Image 1

The prebyterium of the Cathedral of Torcello features an application of the synthronon seat form with the raised cathedra at its head, used when the bishop officiated in his church

surrounded by his priests. Notes the benches, or sedilia, on either side of the altar; although of later provenance, this location and form of seating likely would have served early medieval priest celebrants in lesser churches. Photo credit: Daniel DeGreve

Torcello — Image 2

The templon structure and associated cancelli in the Cathedral of Torcello provide a symbolic separation of the choir and presbyterium

from the nave. Photo credit: Daniel DeGreve

***

Daniel P. DeGreve is an architect with David B. Meleca Architects LLC in Columbus, Ohio, and has contributed articles for both Adoremus Bulletin and Sacred Architecture Journal. Specializing in traditional ecclesiastical architecture and furnishings in addition to urbanism, Daniel has led the design for several church restoration and renovation projects, including that of his native parish in Ohio. He is presently involved in the design of additions and improvements to an 1837 Greek Revival church, which will incorporate a new clergy sedilia inspired by the patterns of Asher Benjamin. Daniel holds a Master of Architectural Design & Urbanism from the University of Notre Dame (2009), and a Bachelor of Architecture from the University of Cincinnati (2002).

Adoremus, Society for the Renewal of the Sacred Liturgy

*