The word “incense” is derived from the Latin incendere, which means “to burn”. It is commonly used as a noun to describe aromatic matter that releases fragrant smoke when ignited, to describe the smoke itself, and as a verb to describe the process of distributing the smoke.

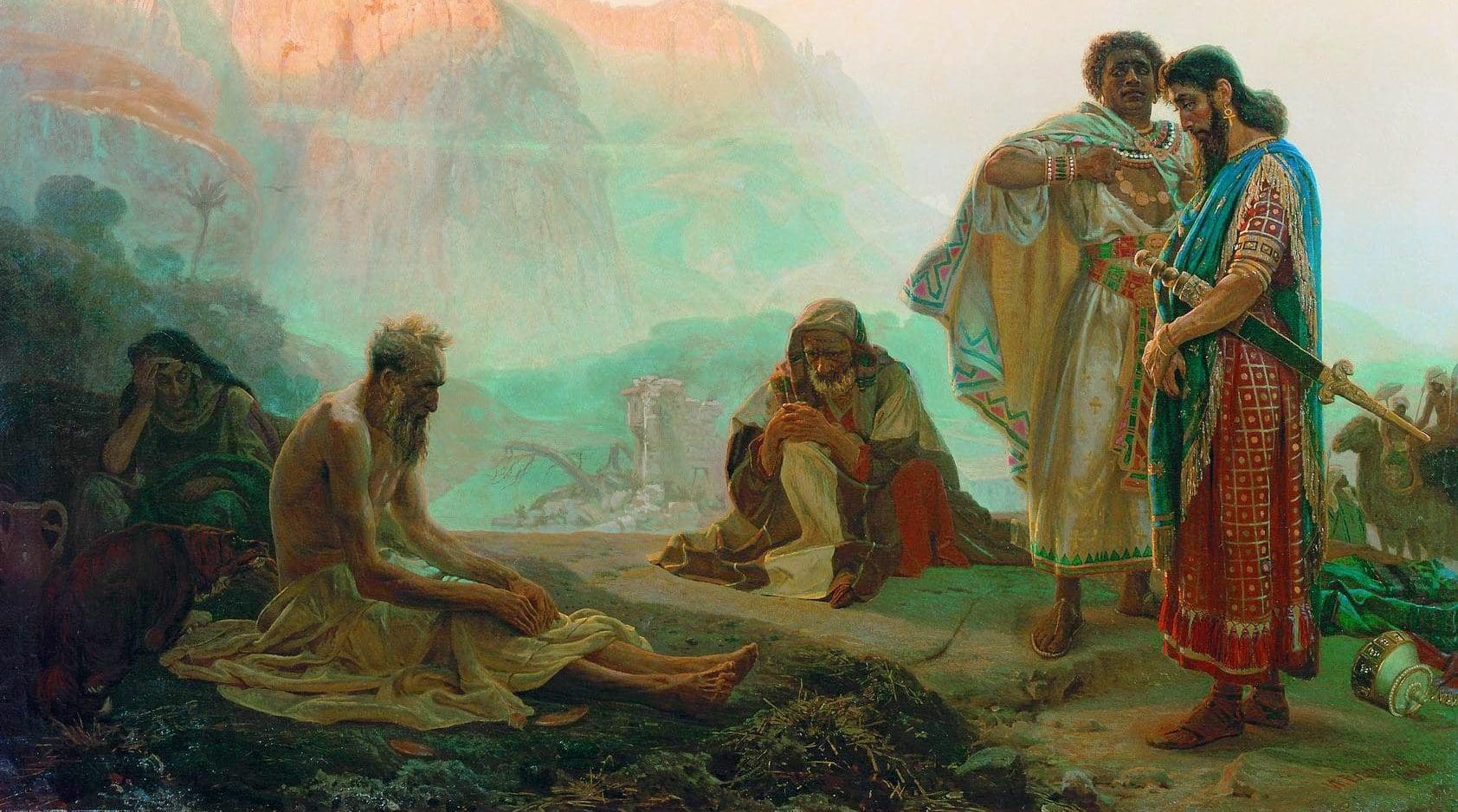

Incense was a highly valuable commodity in ancient times. A gift of incense was something to be prized. The trading of incense and spices provided the economic basis for the famed 1,500-mile-long Middle Eastern Incense Route, which flourished from the third century BC to the second century AD. This route was traversed with caravans of camels beginning in Yemen, crossing Saudi Arabia and Jordan and ending in today’s Israeli port of Gaza. From this port, incense, spices, and other valuable goods were then shipped to Europe. The route made it possible for citizens of the Roman Empire to enjoy the perfume of incenses like frankincense and myrrh, the flavors of different exotic eastern spices, and crucial salts for cooking and preserving food.

The use of incense in religious worship predates Christianity by thousands of years. First in the East (circa 2000 BC in China with the burning of cassia and sandalwood, etc.), and later in the West, incense use has long been an integral part of many religious celebrations. Incense is noted in the Talmud, and the Bible mentions incense 170 times. The use of incense in Jewish temple worship continued well after the establishment of Christianity and certainly influenced the Catholic Church’s use of incense in liturgical celebrations.

The earliest documented history of using incense during a Catholic sacrificial liturgy comes from the Eastern branch of the Church. The rituals of the Divine Liturgies of Saint James and Saint Mark dating from the 5th century include the use of incense. In the Western Church, the 7th century Ordo Romanus VIII of Saint Amand mentions the use of incense during the procession of a bishop to the altar on Good Friday. Documented history of incensing the Evangeliary (Book of Gospels) during the Mass dates from the 11th century. The use of incense within the liturgies continued to be developed over many years into what we are familiar with today.

Why do we use incense?

In the Old Testament God commanded His people to burn incense (e.g., Exodus 30:7, 40:27, inter alia). Incense is a sacramental used to venerate, bless, and sanctify. Its smoke conveys a sense of mystery and awe. It is a reminder of the sweet-smelling presence of our Lord. Its use adds a feeling of solemnity to the Mass. The visual imagery of the smoke and the smell reinforce the transcendence of the Mass linking Heaven with Earth, allowing us to enter into the presence of God. The smoke symbolizes the burning zeal of faith that should consume all Christians, while the fragrance symbolizes Christian virtue.

Incensing may also be viewed in the context of a “burnt offering” given to God. In the Old Testament animal offerings were partially or wholly consumed by fire. In essence, to burn something was to give it to God.

In his monograph Sacred Signs, Monsignor Romano Guardini (1885-1968), who greatly influenced the writings of Pope Benedict XVI, had these beautiful words to say about the use of incense:

The offering of an incense is a generous and beautiful rite. The bright grains of incense are laid upon the red-hot charcoal, the censer is swung, and the fragrant smoke rises in clouds. In the rhythm and the sweetness there is a musical quality; and like music also is the entire lack of practical utility: it is a prodigal waste of precious material. It is a pouring out of unwithholding love.

Sacred Signs, English translation, 1956 St. Louis, Pio Decimo Press.

(ewtn.com/library/liturgy/sacrsign.txt)

Incense and the smoke of burning incense have been offered as gifts to God and to others since ancient times. In a more practical visual sense as the fragrant smoke ascends it also symbolizes our prayers rising to heaven.

The General Instruction of the Roman Missal (GIRM) has this to say about the use of incense:

§ 75 The bread and wine are placed on the altar by the priest to the accompaniment of the prescribed formulas. The priest may incense the gifts placed upon the altar and then incense the cross and the altar itself, so as to signify the Church’s offering and prayer rising like incense in the sight of God. Next, the priest, because of his sacred ministry, and the people, by reason of their baptismal dignity, may be incensed by the deacon or another minister.

Monsignor Guardini also had this beautiful thought about the use of incense within the Mass:

The offering of incense is like Mary’s anointing (of Jesus) at Bethany. It is as free and objectless as beauty. It burns and is consumed like love that lasts through death. And the arid soul still takes his stand and asks the same question: What is the good of it? It is the offering of a sweet savor which Scripture itself tells us is the prayers of the Saints. Incense is the symbol of prayer. Like pure prayer it has in view no object of its own; it asks nothing for itself. It rises like the Gloria at the end of a psalm in adoration and thanksgiving to God for his great glory. (Sacred Signs)

Incense smoke symbolically purifies all that it touches. This is best illustrated by the richly symbolic practice in the Chaldean Rite of the Catholic Church. Those preparing to receive Holy Communion during the Holy Qurbono (Chaldean sacrificial liturgy) first purify their hands by holding them in smoke just above a bowl of burning incense. Similarly in the Maronite Rite of the Catholic Church, as they are being purified prior to liturgical use, the liturgical vessels — chalice, diskos (similar to the paten), and its asterisk (star) cover — are all inverted over the burning incense to catch the fragrant smoke.

How is incense used in the Mass?

The GIRM provides instruction for the use of incense during the celebration of the Mass as follows:

§ 277 The priest, having put incense into the thurible, blesses it with the sign of the Cross, without saying anything.

Before and after an incensation, a profound bow is made to the person or object that is incensed, except for the incensation of the altar and the offerings for the Sacrifice of the Mass.

Three swings of the thurible are used to incense: the Most Blessed Sacrament, a relic of the Holy Cross and images of the Lord exposed for public veneration, the offerings for the Sacrifice of the Mass, the altar cross, the Book of the Gospels, the paschal candle, the Priest, and the people.

Two swings of the thurible are used to incense relics and images of the Saints exposed for public veneration; this should be done, however, only at the beginning of the celebration, following the incensation of the altar.

The altar is incensed with single swings of the thurible in this way:

a) if the altar is freestanding with respect to the wall, the Priest incenses walking around it;

b) if the altar is not freestanding, the Priest incenses it while walking first to the right hand side, then to the left.

The cross, if situated on the altar or near it, is incensed by the Priest before he incenses the altar; otherwise, he incenses it when he passes in front of it.

The Priest incenses the offerings with three swings of the thurible or by making the Sign of the Cross over the offerings with the thurible before going on to incense the cross and the altar.

Where is incense used in the Mass?

Similarly, GIRM 276 allows for the use of incense at the following times during the celebration of Mass:

§ 276 Thurification or incensation is an expression of reverence and of prayer, as is signified in Sacred Scripture (cf. Ps 141 [140]:2; Rev 8:3).

Incense may be used optionally in any form of Mass:

a) during the Entrance Procession;

b) at the beginning of Mass, to incense the cross and the altar;

c) at the procession before the Gospel and the proclamation of the Gospel itself;

d) after the bread and the chalice have been placed on the altar, to incense the offerings, the cross, and the altar, as well as the Priest and the people;

e) at the elevation of the host and the chalice after the Consecration.

Incense is also used on Holy Thursday, during the procession with the Blessed Sacrament to the altar of repose.

At the Easter Vigil, five grains of encapsulated incense (most often made to look like red nails) are embedded in the paschal candle. These five grains of incense represent the five wounds of Jesus Christ — one in each hand, one in each foot, and the spear thrust into His side.

At funeral Masses the earthly remains of the decedent and the catafalque may be incensed, and also the gravesite at the burial service.

Use of incense outside of the Mass

Incense is used by the Church in many areas outside of the Mass. Near the end of the 4th century, the pilgrim Etheria (Silvia) witnessed use of incense at the vigil Office of the Sunday in Jerusalem. Many individuals today (both clerical and lay) include the burning of incense as part of their praying of the Liturgy of the Hours or during private prayers of their own formulation. The Roman Ordos [ritual books] from the 7th to the 14th centuries document the use of incense at the Gospel reading, at the Offertory, and Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament.

Incense is used in various solemn processions, graveside services, the blessing of the dedication of new churches, cemeteries, and items such as new altars, new church bells, new sacred vessels, and newly acquired copies of the Book of Gospels. Incense is also used in the rite of consecrating of the chrism and the blessing of other holy oils, and during the singing of the Gospel canticle at solemn Morning and Evening Prayers of the Divine Office.

Grains of incense are placed into the sepulcher of newly consecrated altars along with the relics of saints to represent the burial rite of the ancient martyrs and to symbolize the prayers of the saint to whom the relic belongs.

Incense is burned atop new altars as they are undergoing the process of consecration prior to their first use.

Finally, frankincense and myrrh are often blessed at the Mass of the Feast of the Epiphany to commemorate the visitation of the Biblical Magi to the Baby Jesus. This incense is distributed to attendees for use at their own family altars and to reserve for use at the coming Easter to prepare their home paschal candles.

The Catholic faith is a liturgical faith. It makes use of all five of our senses: sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch. This is certainly by design as each sense aids us in availing ourselves of the salvific grace flowing from the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. This is precisely why every effort should be used to employ all of our senses whenever possible during the celebration of the sacred liturgy. In more concise terms, the “smells and bells” most certainly do matter.

This article is condensed from a monograph by Mr. Herrera, of San Luis Obispo, California. Complete version: smellsbells.com. His article “Sanctus Bells: Their History and Use in the Catholic Church” was published in the March 2005 Adoremus Bulletin and the Online Edition: February 2012; Vol. XVII, No. 10