Online Edition – December 2005-January 2006

Vol. XI, No. 9

Gregorian Chant —

The Possibilities and Conditions for a Revival

by Monsignor Valentino Miserachs Grau

Is Gregorian Chant returning from exile? asks Sandro Magister, of www.chiesa, prefacing one of the addresses presented at the December 5, 2005 conference on sacred music organized by the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments. The address, by Monsignor Valentino Miserachs Grau, president of the Pontifical Institute of Sacred Music, reflects on restoring chant to the Church’s liturgy. An English translation was published on www.chiesa. It appears here, along with excerpts from Mr. Magister’s comments. — Editor

As on other occasions in the past, this year on December 5 the Vatican Congregation for Divine Worship dedicated one day to the study of sacred music, on the anniversary of the Second Vatican Council’s constitution on the liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium.…

Pope Benedict XVI sent a message to the participants at the congress, encouraging them “to reflect upon and evaluate the relationship between music and the liturgy, always keeping close watch over practice and experimentation”.

The pope’s encouragement was addressed to an assembly composed of musicians and liturgists from many nations, some of whom were in disagreement with him over the matters at hand.

At the end of the work, Cardinal Francis Arinze, Prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship … avoided drawing any conclusions. Cardinal Arinze criticized the musical fashions found in many churches, which he characterized as “chaotic, excessively simplistic, and unsuitable for the liturgy”.…

[T]he day of study did demonstrate a reversal in the trend, back in the direction preferred by Pope Benedict XVI.…

One could gather this from the strong and confident applause that greeted the addresses delivered by Dom Philippe Dupont, abbot of Solesmes and a great cultivator of Gregorian chant, by Martin Baker, choirmaster of the cathedral of Westminster, and by Jean-Marie Bodo, from Cameroon, “where we sing Gregorian chant every Sunday at Mass, because it is the song of the Church”.

But one could gather this above all from the applause that punctuated and concluded the address by Monsignor Valentino Miserachs Grau, president of the Pontifical Institute of Sacred Music in Rome, the liturgical-musical “conservatory” of the Holy See, which has the task of training Church musicians from all over the world.

With concise and concentrated arguments, Miserachs argued forcefully on behalf of the revival of Gregorian chant, beginning with the cathedrals and monasteries, which ought to take the lead in this rebirth. And he called upon the Church of Rome finally to act “with authority” in the area of liturgical music, not simply with documents and exhortations, but by establishing an office with competency in this regard, as it did for example with the pontifical commission dedicated to the Church’s cultural heritage.…

— Sandro Magister

www.chiesa

That the assembly of the faithful, during the celebration of the sacred rites and especially during the Holy Mass, should participate by singing the parts of the Gregorian chant that belong to them, is not only possible — it is ideal.

This is not my opinion, but the thought of the Church. See, in this regard, the documentation from the motu proprio “Inter Sollicitudines” of Saint Pius X until our own time, passing through Pius XII (“Musicae Sacrae Disciplina”), chapter VI of the Second Vatican Council’s constitution on the liturgy, the subsequent instruction issued by the Congregation for Rites in 1967, and the recent chirograph of John Paul II in commemoration of the hundredth anniversary of [Tra le sollecitudini], which was released in 1903. Another example is the statement from the conclusion of the synod of bishops that met last October: “Beginning with their seminary training, priests should be prepared to understand and celebrate the Mass in Latin. They should also […] appreciate the value of Gregorian chant.[…] The faithful themselves should be educated in this regard”.

The motivation for this desire is widely demonstrable, if not self-evident. In fact, the almost outright ban on Latin and Gregorian chant seen over the past forty years is incomprehensible, especially in the Latin countries. It is incomprehensible, and deplorable.

Latin and Gregorian chant, which are deeply linked to the biblical, patristic, and liturgical sources, are part of that “lex orandi” which has been forged over a span of almost twenty centuries. Why should such an amputation take place, and so lightheartedly? It is like cutting off roots — now that there is so much talk of roots.

The obscuring of an entire tradition of prayer formed over two millennia has led to conditions favorable to a heterogeneous and anarchic proliferation of new musical products which, in the majority of cases, have not been able to root themselves in the essential tradition of the Church, bringing about not only a general impoverishment, but also damage that would be difficult to repair, assuming the desire to remedy it were present.

Gregorian chant sung by the assembly not only can be restored — it must be restored, together with the chanting of the “schola” and the celebrants, if a return is desired to the liturgical seriousness, sound form, and universality that should characterize any sort of liturgical music worthy of the name, as Saint Pius X taught and John Paul II repeated, without altering so much as a comma. How could a bunch of insipid tunes stamped out according to the models of the most trivial popular music ever replace the nobility and robustness of the Gregorian melodies, even the most simple ones, which are capable of lifting the hearts of the people up to heaven?

We have undervalued the Christian people’s ability to learn; we have almost forced them to forget the Gregorian melodies that they knew, instead of expanding and deepening their knowledge, including through proper instruction on the meaning of the texts. And instead, we have stuffed them full of banalities.

By cutting the umbilical cord of tradition in this manner, we have deprived the new composers of liturgical music in the living languages — assuming, without conceding, that they have sufficient technical preparation — of the indispensable “humus” for composing in harmony with the spirit of the Church.

We have undervalued — I insist — the people’s ability to learn. It is obvious that not all of the repertoire is suitable for the people: this is a distortion of the rightful participation that is asked of the assembly, as if, in the matter of liturgical chant, the people should be the only protagonist on the stage. We must respect the proper order of things: the people should chant their part, but equal respect should be shown for the role of the “schola”, the cantor, the psalmist, and, naturally, the celebrant and the various ministers, who often prefer not to sing. As John Paul II emphasized in his recent chirograph: “From the good coordination of all — the celebrating priest and the deacon, the acolytes, ministers, lectors, psalmist, ‘schola cantorum’, musicians, cantor, and assembly — emerges the right spiritual atmosphere that makes the moment of the liturgy intense, participatory, and fruitful”.

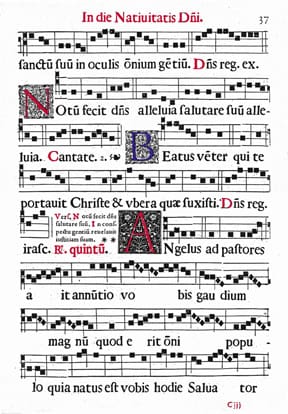

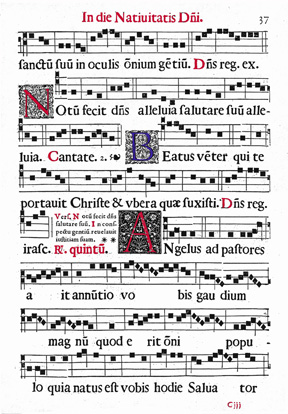

Do we want a revival of Gregorian chant for the assembly? It should begin with the acclamations, the Pater Noster, the ordinary chants of the Mass, especially the Kyrie, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei. In many countries, the people were very familiar with the Credo III, and the entire ordinary of the Mass VIII de Angelis, and not only that! They knew the Pange Lingua, the Salve Regina, and other antiphons. Experience teaches that the people, following a simple invitation, will also sing the Missa Brevis and other easy Gregorian melodies that they know by ear, even if it’s the first time they have sung them. There is a minimal repertoire that must be learned, contained within the “Jubilate Deo” of Paul VI, or in the Liber Cantualis. If the people grow accustomed to singing the Gregorian repertoire suitable for them, they will be in good shape to learn new songs in the living languages — those songs, one understands, worthy of standing beside the Gregorian repertoire, which should always retain its primacy.

A persevering educational effort is called for. This is the first condition for an appropriate and necessary recovery: something we priests often forget, since we are quick to choose the solutions that involve the least effort. Or do we prefer, in the place of substantial spiritual nourishment, to pepper the ear with “pleasant” melodies or the jarring jangling of guitars, forgetting that, as the future pope Pius X incisively pointed out to the clergy of Venice, pleasure has never been the correct criterion for judging in holy things?

A work of formation is necessary. And how can we form the people, if we are not first formed ourselves? The general congress of the Consociatio Internationalis Musicae Sacrae was recently held at the Pontifical Institute of Sacred Music, addressing this very topic — the formation of the clergy in sacred music. For years now, seminarians and men and women religious have lacked a real formation in the musical tradition of the Church, or even the most elementary musical formation. Saint Pius X, and the entire Magisterium of the Church after him, understood very well that no work of reform or recovery is possible without an adequate formation.

One of the most substantial fruits of the motu proprio of 1903 [Tra le sollecitudini], which has continued through time and is being renewed in our day, is the Pontifical Institute of Sacred Music in Rome, which has celebrated the hundredth anniversary of its foundation. How many masters of Gregorian chant, of polyphony, of the organ; how many practitioners of sacred music, scattered to every corner of the Catholic world, have been formed in its halls! Not to mention the other higher schools of sacred music, and even the diocesan schools, and the various courses and seminars of liturgical-musical formation.

But is Gregorian chant really taught there? And how is it taught? Has not the prejudice crept in that Gregorian chant is outdated, to be set aside definitively?

What a serious mistake! I would go so far as to say that without Gregorian chant, the Church is mutilated, and that there cannot be Church music without Gregorian chant.

The great masters of polyphony are even greater when they base themselves upon Gregorian chant, mining it for themes, modes, and rhythmic variations. This spirit imbuing their refined technique and this faithful adherence to the sacred text and the liturgical moment made Palestrina, Lasso, Victoria, Guerrero, Morales, and others great.

The renewal unleashed by Tra le Sollecitudini will be all the more valid as it takes its inspiration from Gregorian chant. At their best, Perosi, Refice, and Bartolucci in our own day made Gregorian chant the essence of their music. And this is not only true in terms of their complex or choral compositions, but also in terms of creating new melodies, in Latin or the vernacular, both for the liturgy and for devotional acts.

True sacred popular singing will be more valid and substantial as it takes its inspiration from Gregorian chant. Pope John Paul II took as his own the principle asserted by Saint Pius X: “A composition for the Church is all the more sacred and liturgical the more its development, inspiration, and flavor approaches the Gregorian melody, and the less worthy it is the more it distinguishes itself from that supreme model”.

But how can one address the creation of a high-quality repertoire for the liturgy, including in the living languages, if the composers refuse to acknowledge Gregorian chant?

Of course, the best school for mastering a repertoire, for penetrating its secrets, is the real-life practice of that repertoire: something that we, the bridge generation between the old and the new, had the fortune to experience.

But unfortunately, after us the curtain fell. Why this resistance to restoring, either completely or partially depending on circumstances, the Mass in Gregorian chant and Latin? Are the generations of today, perhaps, more ignorant than those of the past?

The new Missal proposes the Latin texts of the ordinary in addition to the modern language version. The Church wants this. Why should we lack the courage of conversion?

Gregorian chant must not remain in the preserve of academia, or the concert hall, or recordings; it must not be mummified like a museum exhibit, but must return as living song, sung also by the assembly, which will find that it satisfies their most profound spiritual tensions, and will feel itself to be truly the people of God.

It’s time to break through the inertia, and the shining example must come from the cathedral churches, the major churches, the monasteries, the convents, the seminaries, and the houses of religious formation. And so the humble parishes, too, will end up being “infected” with the supreme beauty of the chant of the Church.

And the persuasive power of Gregorian chant will reverberate, and will consolidate the people in the true sense of Catholicism. And the spirit of Gregorian chant will inform a new breed of compositions, and will guide with the true sensus Ecclesiae the efforts for a proper inculturation.

I would even say that the melodies of the various local traditions, including those of faraway countries with cultures much different from that of Europe, are near relatives of Gregorian chant — and in this sense, too, Gregorian chant is truly universal, capable of being proposed to all and of acting as an amalgam in regard to unity and plurality.

Besides, it is precisely these faraway countries, these cultures which have recently appeared on the horizon of the Catholic Church, that are teaching us to love the traditional chant of the Church. These young Churches of Africa and Asia, together with the ministerial help they are already giving to our tired European Churches, will give us the pride of recognizing, even within chant, the stone that we were carved from. And not a moment too soon!

Two other factors that I maintain are indispensable for the renewal of Gregorian chant and good sacred music are the following:

1. Above all, the musical formation of priests, religious, and the faithful requires seriousness, and the avoidance of the halfhearted amateurishness seen in some volunteers. Those who have gone through great pains to prepare themselves for this service must be hired, and proper remuneration for them secured. In a word, we must know how to spend money on music. It is unthinkable that we should spend money on everything from flowers to banners, but not on music. What sense would it make to encourage young people to study, and then keep them unemployed, if not indeed humiliated or tormented by our whims and our lack of seriousness?

2. The second necessary factor is harmony in action. John Paul II recalled: “The musical aspect of liturgical celebrations cannot be left to improvisation or the decision of individuals, but must be entrusted to well-coordinated leadership, in respect for the norms and competent authorities, as the substantial outcome of an adequate liturgical formation”. So, then, respect for the norms — which is already a widespread desire. We are waiting for authoritative directives, imparted with authority. And the coordination of all the local initiatives and practices is a service that rightfully belongs to the Church of Rome, to the Holy See. This is the opportune moment, and there is no time to waste.

Reprinted with permission of www.chiesa. (See the English home page: http://www.chiesa.espressonline.it)

The web site of the Pontifical Institute of Sacred Music offers a collection of downloadable music files from the Institute: www.vatican.va/roman_curia/ institutions_connected/sacmus/documents/rc_ic_sacmus_sound_en.html

***

*