Online Edition

– Vol. IX, No. 2: April 2003

Chanting in the Vernacular

A Song Both Old and New

by Father Basil Foote, OSB

Among the musical questions raised by the promulgation of the Second Vatican Council’s Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy (

) in 1963 was the possibility of combining the existing Gregorian Chant of the Latin Church with vernacular texts. Three attitudes became apparent:

1) It was out of the question — Latin is integral to the chant melodies, which would be inconceivable in a vernacular version;

2) The thing could be done, but the incomparable lines of the chants must remain virtually intact;

3) The thing could be done, but if it was going to be convincing in English (the vernacular tongue under consideration here), the melodies could not be left intact, but would have to be tampered with.

The first solution is simple enough, and needs no further comment. The second and third do, because both have been tried; and it is the purpose of this article to comment on both, particularly the last.

A necessary point must be established here, namely that a translation, and on top of that, a musical adaptation, is a second-hand thing. Shakespeare has not quite the same force in German, nor Goethe in English. Something is going to be lost, however much of the sense of the original might be conveyed, and however much the translation is worthwhile. In the case of Gregorian Chant, there is the added factor of an intimate wedding of text and melody, and whether one subscribes to the "accentual" theory of Gregorian rhythm, whereby the flow of melody depends on the Latin word-accent, or the Solesmes theory, in which the beats of the melody are subtly syncopated on non-accented syllables, one thing is clear: melody is inseparably bound up with text — and more exactly, with a Latin text.

Yet attempts have been made to sing Gregorian Chant in the vernacular. In Germany, for instance, some chants of the funeral rite were used in this manner — albeit in simple, syllabic verses — decades before Vatican II. Several outstanding Anglican musicians had turned their attention to this endeavor since the late 1800s, and one or other of their Catholic colleagues followed suit in the mid-1960s. Without the slightest disrespect for the undoubted musical expertise of these men, it must be said that their efforts have not met with wide acceptance. A language of strong stress and indefinite vowel sounds (English) cannot be forced into a set of melodic molds that were made for another language of subtle stress and pure vowels (Latin); the result is artificial and unconvincing — or rather, convincing that such an attempt should not be made in the first place.

We are left with the third alternative: an approach that bases itself on the premise that, if the vernacular text is English, the music must fit it and not vice-versa, and if something has to "give" in order to achieve this, it must be the melodic line. Turning to the music itself, one can discover three degrees of complexity, and each will be briefly illustrated.

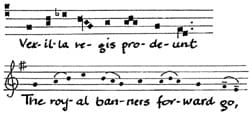

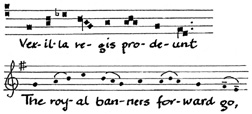

There is a handful of Latin chants which, happily, lend themselves to vernacular transfer with virtually no alteration —

There is a second category that looks easily adaptable, but contains areas of subtle rhythmic nuances that will not get by in English. It is precisely here that a sense of wedding melodic rhythm to textual accent must come into play.

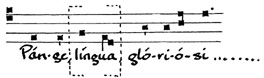

A good example is the well-known Latin hymn "

Pange Lingua

".

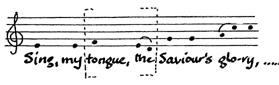

Literal rendering into English seems easily possible for the

most part, but there are two places — the first and last lines

— where just one shift of melodic accent that would fit the

English has, alas, been missed —

Note the areas enclosed by the dotted lines. In the first instance, the accent of "

lingua

" is on the first syllable, but the melodic stress falls on the two-note group over the second; and the same thing happens at the last line. With Latin, this kind of thing poses no problem, because the Latin accent is light; and indeed, the "syncopation" brought about by playing word accent against note accent is really the beauty of Gregorian chant — its particular form of wedding text to music. But now let us set these two sections down in English, note-for-note the same as the Latin —

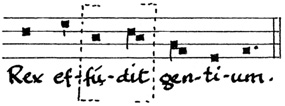

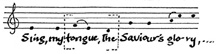

Note the same areas, but look what has happened to the English: the note pattern has thrown the word accent abruptly from "tongue" to "the", and from "King" to "of" — and the result is not happy. The solution? The two-note group is simply shifted to the accented words "tongue" and "King"; the melody does not change but the accent does: it is now where it should be, and the effect is satisfying "English", and sings itself naturally —

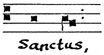

Still in this second category, take the example of the Sanctus of the Mass "

Kyrie Genitor Alme

" (XVIII):

Notice how the Latin word accent is on the first syllable of "

Sanctus

", but the melodic stress falls on the following two-note group. This is the heart of that subtle syncopation mentioned above, so easy with the Latin. Not so with English, and the temptation to render this chant exactly the same will prove fatal —

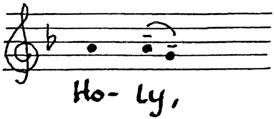

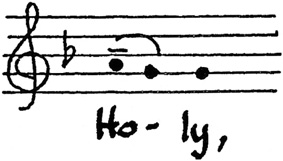

The solution, again, is to shift the two-note group to fit the stress of "Ho-ly" —

The third type of chant melodies comprises those of greater complexity, i.e., not confined to one-, two-, or at most three-note groups, but involving floating melismas of many notes over one syllable. One might very rarely find an opportunity to exploit these over a round "o" as in "low", or "a" as in "father", but there are too many other sounds in English like the "e" in "the", and to try one of these over a multi-note group is to court ridicule. The only realistic approach here is that of radically "streamlining" the entire piece, keeping only to the broadest outline of the original — or not to touch it at all.

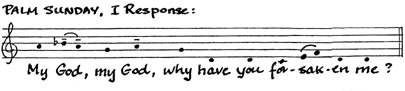

One might suspect that there is yet another category, a further step in the Englishing of plainsong. There is, and the last-mentioned two expressions are indicative, namely, of a whole new body of music — English Plainsong. It is not difficult, given a sufficient familiarity with Gregorian Chant and with adapting it to English as described in the foregoing, to launch out into original settings of liturgical texts, utilizing the eight Gregorian modes and a rather free-flowing syllabic style. Here is an example, a short response after the first reading at the Eucharist:

Can this kind of church music succeed? This writer is convinced that it can.

In the years since the Council we have been offered quite an array of liturgical music — all of it well intentioned, no doubt, but in all too many cases striving so hard to be "timely", "joyful", "meaningful", or whatever else, that the very attempt has guaranteed a short life.

But the modes of plainsong are capable of limitless subtleties of expression, so ideal for the differing moods of feasts or seasons; its God-centered flavor, based as it is upon Scriptural texts, is objective, obliging us to make its sentiments our own; its simplicity deceptive, inviting us to acquire a taste for it — a discipline necessary for the experience of any great music.

Above all, the Chant is prayer. Its free rhythm, springing from the words themselves, lets those words speak spontaneously; they become, as it were, "spoken musically". And surely, if prayer is what the Liturgy is all about, then the music by which one can pray best deserves first place — Gregorian chant preserved and flourishing as the Church’s priceless heritage, and a new English Plainsong complementing it and adapting its spirit to a wide participation among the faithful.

Surely this is to sing to the Lord a song both old and new, a song ever timely because it is timeless.

***

Father Basil Foote, OSB, is organist and assistant choirmaster at Westminster Abbey Mission, British Columbia, Canada. He has served on the Music Sub-Committee of the International Commission on English in the Liturgy (ICEL). This essay originally appeared in 1984 in the (now defunct) Canadian Catholic Review, and it is reprinted here with the author’s permission.

***

*