The Divine Office—also known as the Liturgy of the Hours—sanctifies time and allows God to find us in the maelstrom of our daily tasks and chores. In a day when to-do lists and the “Buy Now” button on websites seem to dictate how we live our lives, we expect things to be accomplished as soon as possible. Even as Christians, we enter Advent’s simplicity and look longingly toward the glories of Christmas; we run into Lent with every ounce of good zeal we possess because we have fixed our sights on Easter; or we drift into Ordinary Time and misconstrue its “ordinal” nature for mere “ordinariness.” It is human nature not to be content with what we have or with who we are—we want the newest gadget or book, and we fantasize about the future that lies in store for each of us. We want fulfillment and we want it now, despite forgetting that we live in the period of “already but not yet.”

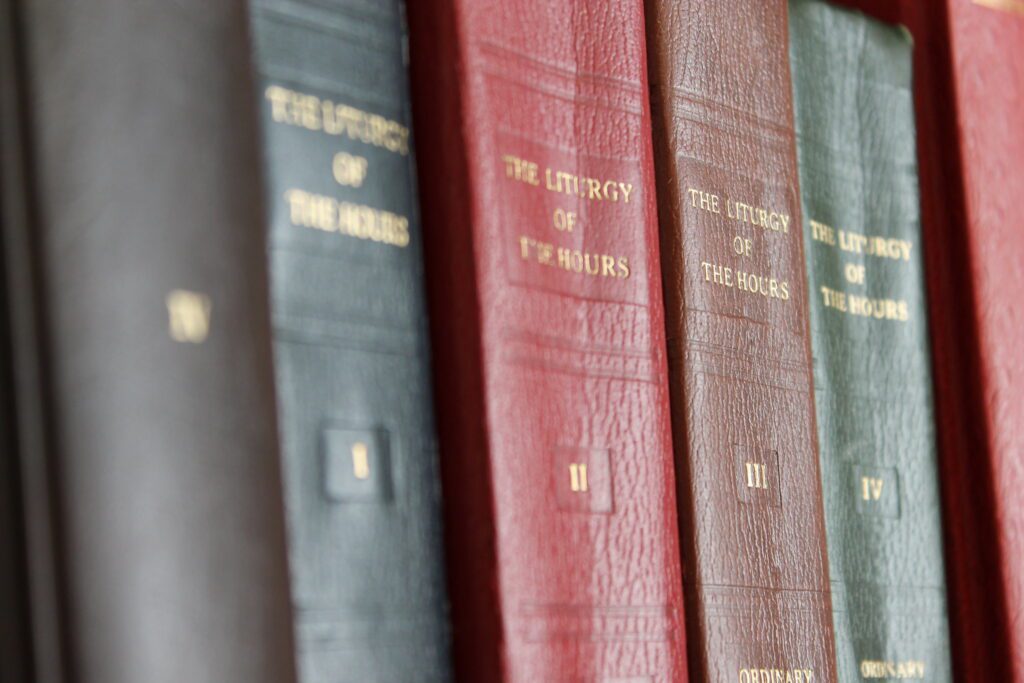

This is not the case only for liturgical seasons, but also for the Second Edition of the Liturgy of the Hours, a task of renewal that has been delayed time and time again over the past decade or so. We desperately want this refined edition of the Liturgy of the Hours to be in our hands because of its perceived “new” spiritual benefits, not to mention the novelty of becoming acquainted with a new edition of a liturgical book. Yet, the Liturgy of the Hours as a liturgical act is intended to sanctify time: past, future, and most definitely the present moment. Now is the right time to remind ourselves about the spiritual benefits of our current edition of the Liturgy of the Hours—how it has nurtured our spiritual lives and anchored us to the timelessness of Christ while keeping us stable within the vicissitudes of our times. In this manner, we can help ourselves to stay in 2024 and be content with the gift that the Church gave us in 1975.

The Liturgy of the Hours as a liturgical act is intended to sanctify time: past, future, and most definitely the present moment.

Text and Context

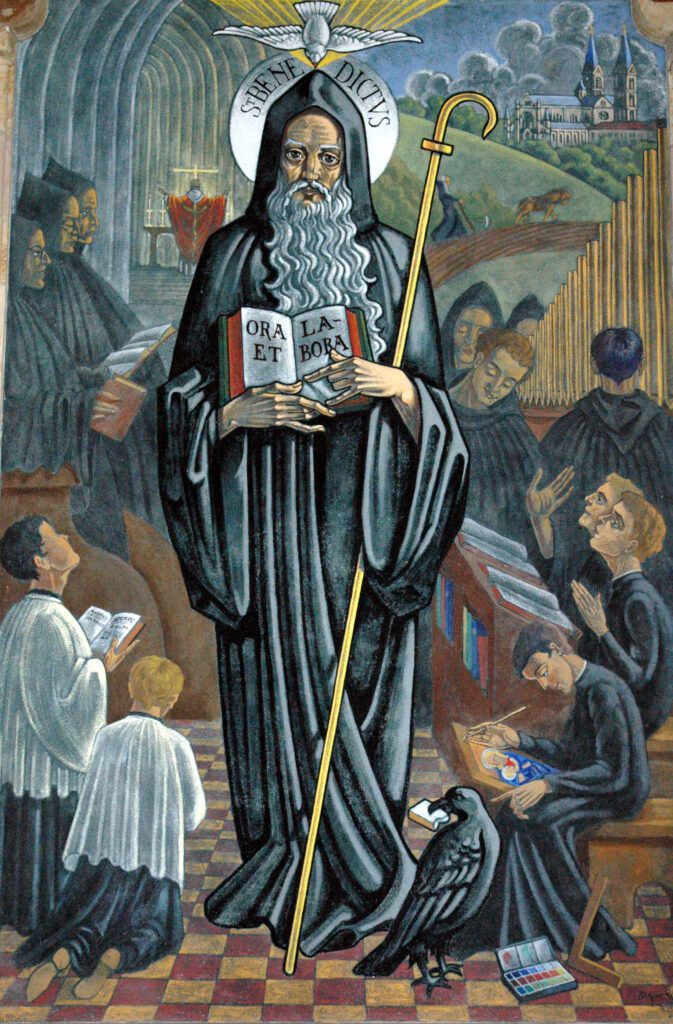

I approach the topics of the Liturgy of the Hours and contentment from numerous contexts. I am a Benedictine monk, obliged to pray the Divine Office in its entirety every day for my salvation and for the salvation of the world. I understand my vocation as one lived for Christ and his flock, an enterprise that edifies me and enables me to cocreate with God. I was not always a monk, though. I began praying the Liturgy of the Hours toward the end of my undergraduate career, something I continued once I became a graduate student at the Liturgical Institute in Mundelein, IL, in 2010. As a member of a community of priests, religious, and lay people who lived, worked, and prayed together, I saw how our common celebrations of Lauds and Vespers throughout the week provided a needed respite amid classroom and house assignments. The conscious, fruitful, actual, and deliberate chanting gave me permission not to think about the earthly and transient concerns that often plague the minds of graduate students. Indeed, the Liturgy of the Hours provided a way for me to frame the day; to become content with the way things are, not the way I want them.

After stints as a diocesan seminarian, an archivist, and a high school teacher, in 2016, I found the road that led me to Saint Meinrad Archabbey. My commitment to the Office waxed and waned throughout the time between being a seminarian and becoming a monk. Despite the fluctuating intensity of my devotion to the Office, I kept desiring to immerse myself in the emotionally charged poetry of the psalms and the wisdom of our ancestors in the faith. Within the simple beauty of the 1963 Grail Psalms and annual cycle of readings, I came to understand that the discipline required by the Liturgy of the Hours gives an overwhelming sense of peace and contentment to my day, as well as structure and accountability. I would never claim to be a “good monk,” but the way the Liturgy of the Hours punctuates my days has made me more aware that ultimate contentment can be found nowhere except in our Loving and Triune God.

Guide for the Perplexed

Father Ron Kunkel, one of my professors at the Liturgical Institute, once encouraged my classmates to read The General Instruction of the Liturgy of the Hours (GILH) at the beginning of Advent each year. Kunkel explained that such an act would deepen our appreciation of the Office. The GILH gives us the practical necessities of celebrating the Divine Office with care and diligence, but it also hands onto us the vision of how the Liturgy of the Hours sanctifies time and unites us to Christ and his Mystical Body throughout all of time.

For example, we are reminded, “The testimony of the early Church shows that individual faithful also devoted themselves to prayer at certain hours…. In the course of time other hours were also sanctified by communal prayer, hours which the Fathers judged were found in the Acts of the Apostles” (GILH, 1). The GILH calls to mind how the Liturgy, though the Work of God, is also a work of the people—through our incorporation into the Mystical Body at our baptism, God has given us the charge to cocreate with him. The Liturgy of the Hours has its roots in Jewish Temple worship, and Christians practically began adapting the rituals of the Temple in their emerging Christian worship.

As a member of a community of priests, religious, and lay people who lived, worked, and prayed together, I saw how our common celebrations of Lauds and Vespers throughout the week provided a needed respite amid classroom and house assignments.

As the liturgical sanctification of time progressed and evolved in the early Church, the theology of the Trinity also became clearer to Christians. The liturgical hours gave to the Church a decidedly structured approach to the day, and it also offered to Christians a pattern for how to live a life centered in the triune-love of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. “Thus in the heart of Christ the praise of God finds expression in human words of adoration, propitiation and intercession; the head of renewed humanity and mediator of God prays to the Father in the name of and for the good of all mankind” (GILH, 3). When the members of Christ’s Church gather for worship, they are assembled into one Body, the Body of Christ on earth. As the GILH notes, the liturgy is the location where Christians pray as Christ prays to the Father in the Spirit: “A close and special bond exists between Christ and those whom, through the sacrament of regeneration, he makes members of his body, the Church. All the riches belonging to the Son flow from him as from the head into the whole body: the pouring out of the Spirit, truth, life and a share in his divine sonship, which he revealed to us in all his prayer on earth” (GILH, 7).

God takes the initiative to sanctify time, an ongoing and generative endeavor to which all who confess the name of Christ should (and must) attend in the world. To phrase that in another manner, “There can be no Christian prayer without the action of the Holy Spirit. He unites the whole Church and leads us through the Son to the Father” (GILH, 8).

The Second Edition of the Liturgy of the Hours has been delayed time and time again over the past decade or so. We desperately want this refined edition of the Liturgy of the Hours to be in our hands because of its perceived “new” spiritual benefits, not to mention the novelty of becoming acquainted with a new edition of a liturgical book. Until it appears, now is the right time to remind ourselves about the spiritual benefits of our current edition of the Liturgy of the Hours—how it has nurtured our spiritual lives and anchored us to the timelessness of Christ while keeping us stable within the vicissitudes of our times. Image Source: AB/St. Joseph on Flickr

With this schema for how Christians ought to live in the world, the GILH once more affirms that God’s grace diffuses throughout all times and places. “Compared with other liturgical actions, the particular characteristic which ancient tradition has attached to the Liturgy of the Hours is that it should consecrate the course of day and night” (GILH, 10). The sanctification of time and of humankind is a dialogue that ceaselessly echoes in our whole being, precisely because it is the dialogue of the Son offering eternal worship to the Father in the Spirit. “For in the liturgy God speaks to His people and Christ is still proclaiming His gospel. And the people reply to God both by song and prayer” (Sacrosanctum Concilium, 33). Just as Christ offers to the Father this oblation in the Spirit in heaven, we are called to participate in that eternal and timeless worship even now in our earthly lives, offering ourselves as an oblation pleasing to the Father. It is through the members of his Mystical Body on earth that Christ’s work is manifested and the work of ushering in the Kingdom of God continues.

God, Presently

The timelessness of God was something I never doubted, though I gained a much deeper understanding of this fact when one of my theology professors stunned me with a divine revelation—of sorts. Dr. Keith Lemna, a professor of theology at the Saint Meinrad Seminary & School of Theology, once said in a lecture that “God sees all time—past, present, and future—occurring as the present moment.” Before that lecture in 2018, I knew that to be true in an objective sense, though after that comment, I was given a tailormade example of how I relate to Father, Son, and Spirit. I never forgot such simple wisdom, and it has guided my inner life and outward prayer ever since.

The Divine Office is something that is very much an earthly undertaking that God’s grace imbues with “hidden lessons of the past” (Psalm 77:2) for us to see how we work with God’s assistance throughout the course of each day, second to second and moment to moment. In my study of theology and in my liturgical prayer, I came to grow in love of God and in love of neighbor—I saw in the eternal dialogue of Father, Son, and Spirit the model on which I must base my life: love, mercy, humility, justice, hospitality, and mutual obedience. I encountered these monastic virtues in praying the Liturgy of the Hours, even before I was a monk.

The numerous components of the Liturgy of the Hours—the hymns, the beautifully composed chant modes of The Mundelein Psalter, and the 1963 Grail translation of the Psalms—fostered in me the desire to know God and who he is: a loving Creator who cares for his creatures, who loves them to such an extent that he willingly took on the sins of the world to deliver from eternal perdition those same creatures who once were deprived of his glory. The cyclical nature of the Office and the liturgical year reiterate for me how we as Christians are called to pray ceaselessly and offer thanks to God throughout all our days and so enter that glory of which our primordial parents deprived us.

The liturgical hours gave to the Church a decidedly structured approach to the day, and it also offered to Christians a pattern for how to live a life centered in the triune-love of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

The liturgical prayer of which I write did not have an idealized “formal translation” of the Psalter, and a number of those hymns were not composed from and within the Church’s rich tradition of liturgical music. The liturgical prayer that sustained me and helped me to understand my vocation as a child of God and as a Benedictine monk is found in the Liturgy of the Hours that went into effect in 1975. It is what was placed in my hands, to pray and to cherish, a gift that I, in turn, am meant to hand on in living out my baptismal promises and my monastic vows.

Even now, with the publication date of the second edition of the Liturgy of the Hours being delayed yet again, I can utilize God’s gift of memory to aid in keeping me stable and grounded in the present moment. I do not have to look back to some fantasized past version of myself, nor am I straining my gaze over the horizon for a new version of the Office that never seems to materialize. I am a Benedictine monk whose vocation is to pray the Office for my salvation and for the salvation of the whole world in the here-and-now of southern Indiana. For this, and for all the aforementioned liturgical insights and micro-revelations I have received in my quest for daily sanctification, I am content.