A friend of mine has recently taken to using his digital calendar to remind him to pray for people on the anniversaries of their death. If he lives long enough, every day of the year will have at least one soul for him to commend to the mercy of God. The natural human instinct to commemorate the dead has been baptized, so to speak, by the theology of the communion of saints, that fellowship of all the members of the Mystical Body of Christ. Blessed as we are to be “surrounded by a cloud of witnesses” (Hebrews 1:12), we pilgrim faithful on earth honor the saints in heaven by keeping their feast days and soliciting their prayers, while also praying for the souls in purgatory who are being fitted for glory.

The Catholic Church, being much older than my friend, has for a very long time been calling to mind daily lists of men and women whom she numbers among the citizens of the heavenly Jerusalem. What enables this recollection is a sort of memory-bank called the Roman Martyrology (Martyrologium Romanum, to give its Latin name), a catalog of the saints arranged according to their feast days as found in the Church’s liturgical calendar. It is one of the official liturgical books of the Roman Rite, and this article is a basic introduction to its origins, contents, and use in the liturgy.

Pre-History

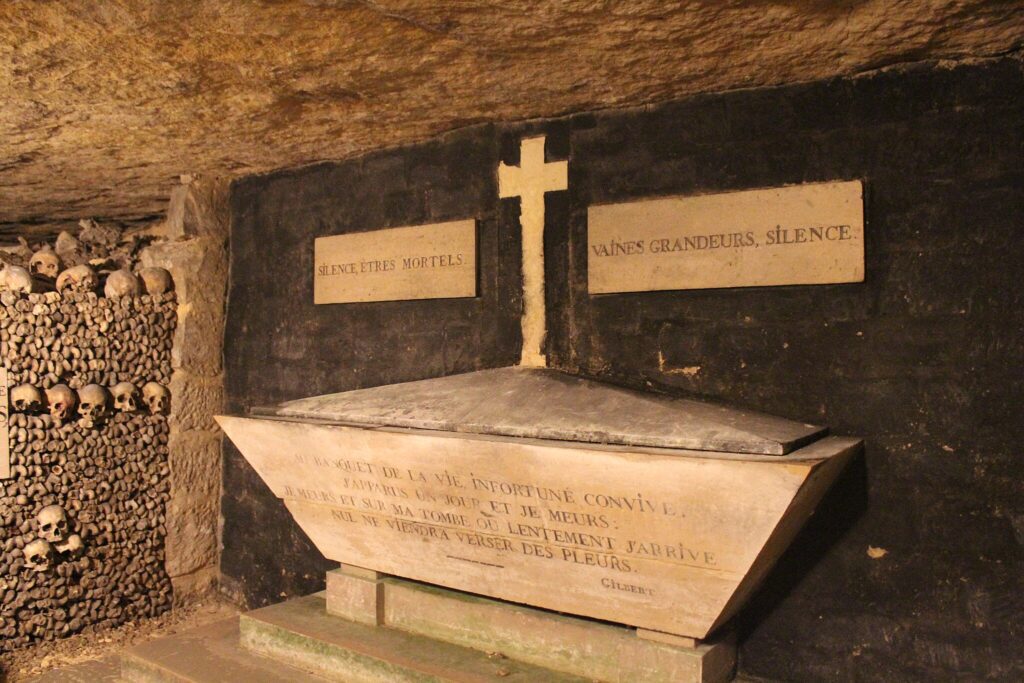

The word “martyr” derives from the Greek martus, “witness.”1 In the Christian context, a martyrology was originally a list of those who were put to death willingly for bearing witness to Jesus Christ.2 From very early times the Church kept written records of the martyrs as they fell. Pope St. Clement in the last years of the first century appointed notaries to provide for this need.3 During the Decian persecution in the mid-third century, St. Cyprian, bishop of Carthage in Roman Africa, instructed his clergy to note carefully the day of a martyr’s death. (Cyprian himself was martyred in 258.) The early Christians commemorated the martyrs by gathering at their tombs to celebrate the Eucharist on the anniversary of their death (their dies natalis, that is, their “birthday” into heaven).4

In the course of time, each local Church developed its own martyrology. These local martyrologies were little more than annotated calendars, lists of martyrs arranged in the order of their anniversaries, sometimes including the location of their bodies and how they died. Little by little these local lists were enriched by the names of martyrs from neighboring Churches; thus the Church at Rome celebrated the anniversary of the Carthaginian martyrs Perpetua and Felicity on March 7, and that of the aforementioned Bishop Cyprian on September 14. Gradually the martyrologies came to include, besides the “red” martyrs who shed their blood in imitation of Christ’s own Passion and Death, the “white” martyrs who exhibited heroic virtue, endured many trials and made great sacrifices, yet died a natural death. Anniversaries of dedications of churches and of various other occasions also gained a place in the local martyrologies.

The word “martyr” derives from the Greek martus, “witness.”

The “general” martyrology was a compilation of these local martyrologies, whether few or many, sometimes with borrowings from extraneous sources. Among the general martyrologies the best known is the Hieronymian, so called because it was, albeit falsely, attributed to St. Jerome (347-420). Compiled in northern Italy in the mid-fifth century and revised in Gaul around 600, the Hieronymian Martyrology as it has reached us combines a list of martyrs and popes venerated at Rome (dating to 354), a series of local martyrologies of Gaul, some literary sources such as Eusebius of Caesarea’s Ecclesiastical History (early fourth century), and general martyrologies of Italy, Africa, and the Eastern Churches. It consists of some ten thousand saints, in most cases with no further information than the place where they were commemorated.

As the period of the early persecutions grew more distant, such brief notices did not satisfy the popular desire for more information, and so there appeared a new type of martyrology called the “historical.” The historical martyrologies included brief biographies or eulogies (elogia, in Latin) of the saints. St. Bede the Venerable (672-735) compiled the first of this kind; in his own words, he had diligently striven “to set down all whom I could find and not only on what day, but also by what manner of contest and under what judge they overcame the world.”5 His sources were chiefly the Hieronymian Martyrology, 50 acts or “passions” of martyrs, and various patristic and ecclesiastical authors.

As the period of the early persecutions grew more distant, such brief notices did not satisfy the popular desire for more information, and so there appeared a new type of martyrology called the “historical.”

Bede was followed by other martyrologists (all of the ninth century) who utilized his work more or less, but “without always following his learned caution in leaving a day blank when there was nothing to place against it.”6 Three of these are of particular relevance: Florus, deacon of Lyons, who considerably added to Bede’s entries and furnished valuable historical and topographical notes; the monk St. Ado (later archbishop of Vienne), who appears to have made fraudulent use of Florus’s work;7 and Usuard, a contemporary of Ado and a monk of Saint-Germain-des-Prés at Paris, who relied directly on Ado and on the other sources previously mentioned. It is the line of development from Bede to Usuard that leads to the Roman Martyrology.

From Trent to the Present

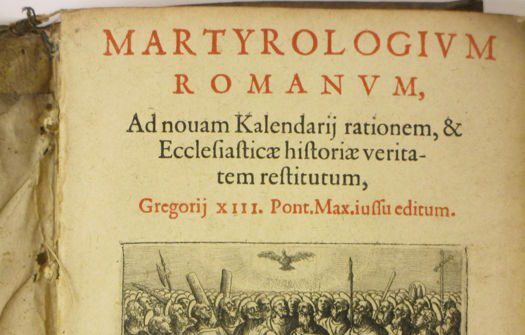

Of all the medieval martyrologies, Usuard’s was the most widely circulated. By the 16th century it had displaced the earlier books in most churches and monasteries. As part of the general reform of the liturgy after the Council of Trent (1545-63), Pope Gregory XIII in 1580 appointed a small commission (7-10 members) under the learned Cardinal Guglielmo Sirleto to make one martyrology that would embrace and supersede all others. The result of their work was the Martyrologium Romanum published in 1584 and made obligatory for the Latin Church.8 The book rests mainly on Usuard, completed by various writings of the Church Fathers, especially the Dialogues of Pope St. Gregory the Great (sixth century), and various Italian martyrologies; for the saints of the Greek Church it uses an ancient menology9 translated into Latin by Cardinal Sirleto.

The Roman Martyrology has undergone many revisions and updates since 1584.10 By the turn of the 20th century, generations of scholars had been keenly aware that the book suffered from the errors of its original sources—legendary accretions, incorrect dates and places, confusions of names of persons with those of places, etc.11 Mistakes were made not only by the compilers of the old martyrologies but by their revisers later on. Accordingly, the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) decreed in its Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy: “The accounts of martyrdom or the lives of the saints are to accord with the facts of history.”12

The application of critical history to the existing Roman Martyrology would require much work over a long period of time. This is why the Martyrology was the last Roman liturgical book to be revised after Vatican II. Not until 2001 did the first Latin “typical edition” appear. A revised edition was issued in 2004 and still awaits an approved English translation.13

The 2004 Martyrologium Romanum is an 845-page hardbound volume listing some 7,000 saints and blesseds. It is organized as follows (page numbers in brackets):

-

-

- The “Praenotanda” giving a theological and pastoral introduction [9-22];

- An explanation of the lunar day [23-26];14

- The Orders of Reading of the Martyrology (I) within and (II) outside the Liturgy of the Hours [27-32];

- The notices for the movable feasts [33-38];

- Short optional biblical readings (Proper of Time, Proper of Saints, and Commons) [39-60];

- Orations (collects) [61-68];

- Chant settings for the daily notices and for the Proclamation of the Lord’s Nativity [69-74];

- The Martyrology proper, arranged from January through December [75-696];

- Alphabetical index of names [697-844];15

- General index [845].

-

The new Roman Martyrology maintains the characteristic elements of its predecessors. The saints are arranged by the date on which they are commemorated, with (in most cases) a short notice (eulogy) of their life and death.16 Each day has a heading with the Roman date and a table that gives the status of the lunar cycle.17 A large number of saints from the old Martyrology were expunged whose accounts are regarded as more legend than fact, or whose very existence is uncertain. In other cases the “questionable” saints were not deleted, but their eulogies were cautiously rewritten.18 It may surprise some to learn that St. Valentine (February 14)19 and St. Christopher (July 25)20 remain in the Martyrology, even though they were famously removed from the General Roman Calendar in 1969.21

It is worth mentioning the presence of Old Testament saints in both the old and new editions of the Martyrology: Abraham (October 9), Moses (September 4), David (December 29), the prophets, and “all the holy ancestors of Jesus Christ, son of David, son of Adam” (December 24). The Church is directly in continuity with the Jews of old who confessed Jesus of Nazareth as Israel’s Messiah, and so is rooted in the biblical patriarchs and prophets.22

Noteworthy, too, is the inclusion of several non-Catholic saints, such as the 10th-century Armenian mystic Gregory of Narek (February 27), who in 2015 was declared a Doctor of the Universal Church, and two 14th-century Russian Orthodox saints: the missionary-bishop Stephen of Perm (April 26) and the monastic reformer Sergius of Radonezh (September 25).23 In May 2023, Pope Francis inserted into the Martyrology the 21 Coptic Orthodox martyrs who on February 15, 2015, were beheaded on a beach in Libya by Islamic State terrorists.

Obviously the number of saints venerated by the Church grows with each new canonization—and there have been several hundreds since the Roman Martyrology was last published.24 The eulogies for newly beatified and newly canonized persons are prepared by the Dicastery for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments and are usually published in the official acts of the Holy See, Acta Apostolicæ Sedis (available online at www.vatican.va).

It is worth mentioning the presence of Old Testament saints in both the old and new editions of the Martyrology: Abraham (October 9), Moses (September 4), David (December 29), the prophets, and “all the holy ancestors of Jesus Christ, son of David, son of Adam” (December 24).

The Roman Martyrology in the Liturgy

The liturgical use of martyrologies throughout the Latin Church dates to at least to the ninth century. 25 Following the pre-modern convention that the day begins not at midnight but at the previous sunset, the saints’ names were read out on the day before their feast day in choir at the office of Prime, the first of the canonical hours of the Divine Office. Although Prime was abolished at Vatican II, 26 the Martyrology retains a place in the modern Roman Rite: it may be read either on its own or as part of the Liturgy of the Hours, preferably after the concluding prayer at Lauds (morning prayer).27 In keeping with traditional practice, the entire portion of the Martyrology assigned for a particular day is always read on the previous day;28 the sole exception to this rule being Easter Sunday.29 Celebration in choir is recommended, but it has been the custom in many seminaries and religious houses to read the Martyrology in the refectory before or after the evening meal.

The Order of Reading of the Martyrology begins with the reader announcing the (coming) day of the month and, optionally, the day of the moon in the lunar cycle. Then is read or sung the eulogies of the saints; if, however, the day coincides with a movable feast, the notice of the feast comes first. The reading is followed by the versicle and response: “Precious in the sight of the Lord: Is the death of his Saints” (Psalm 116:15). A short Scripture reading may follow, with the usual acclamation and response: “The word of the Lord. Thanks be to God.” Next, the one who presides (ordinarily a priest or deacon) prays the oration or collect.30 The celebration concludes with the blessing and dismissal,31 but with the novel feature of a prayer for the faithful departed inserted between the two. 32

For most of the Catholic faithful, the one opportunity of experiencing the Martyrology is at church on late Christmas Eve: the Proclamation of the Lord’s Nativity

Generally, when a saint’s feast falls on a Sunday, the Mass and Office of the saint is not celebrated. 33 But this does not mean the saint’s feast has been “canceled.” By means of the Martyrology, the feast is in fact liturgically celebrated, albeit in an attenuated way. On ferial days and on days that admit celebration of the optional memorial of a saint, one may celebrate the Office and Mass of any saint ascribed to that day in the Martyrology. 34

Open and Marvel…

Almost a quarter of a century after its publication, the new(ish) Roman Martyrology has not secured a foothold in the liturgical life of the Church. This is regrettable but unsurprising, given the virtual disappearance (except where the pre-conciliar rites are celebrated) of Prime, the Martyrology’s age-old companion, and the dearth of vernacular translations. For most of the Catholic faithful, the one opportunity of experiencing the Martyrology is at church on late Christmas Eve: the Proclamation of the Lord’s Nativity, which is the first of the Martyrology entries for December 25, may be sung or recited before the Mass during the Night.35

As delightful as it is to hear that Proclamation sung well, this is merely to touch the binding of the Church’s “book of life” (if I may so appropriate a biblical metaphor): Christ being the bond uniting the saints to himself and one another. To open its pages is to marvel at the myriad ways of glorifying Christ in our bodies, whether by life or by death (see Philippians 1:20-21).

Father Thomas Kocik is a priest of the Diocese of Fall River, MA. He has served as a parish priest, hospital chaplain, theology instructor and, most recently, chaplain to the Latin Mass Apostolate of Cape Cod. He is a member of the Society for Catholic Liturgy and former editor of its journal, Antiphon. Among his many published works are The Reform of the Reform? A Liturgical Debate (Ignatius Press, 2003) and Singing His Song: A Short Introduction to the Liturgical Movement (Chorabooks, 2019). A complete bibliography is available at https://thomaskocik.academia.edu.

Footnotes

- It was not until the Christian literature of the mid-second century that martus signified dying for a cause. “When it finally assumed that sense, its meaning of ‘witness’ began to slip away, so that the word ‘martyr’ in Greek and the same word borrowed in Latin came more and more to mean what it means today.” G. W. Bowersock, Martyrdom and Rome (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 5.

- While “martyrology” is the most frequent word in use in the Latin Church, other terms such as “legendaries” and “passionaries” are also found. In the Eastern Churches one has the “menology” and “synaxary.”

- As recorded in the Liber Pontificalis, a collection of papal biographies from St. Peter onward. This book was begun anonymously in the sixth century and was continuously (though intermittently) amended, enlarged, and abridged until the late Middle Ages.

- The commemoration of St. Polycarp, for example, was instituted at Smyrna immediately after his death in 155. Having collected the martyred bishop’s bones, says the account, “We laid them in a place befitting them. May the Lord grant us to meet again there, when in gladness and joy we can celebrate the anniversary day of his martyrdom….” Lancelot C. Sheppard, The Liturgical Books (vol. 109 of The Twentieth Century Encyclopedia of Catholicism) (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1962), 55.

- Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation, book 5, chap. 24; quoted in Sheppard, The Liturgical Books, 59.

- Sheppard, The Liturgical Books, 59.

- As demonstrated in Henri Quentin, Les Martyrologes historiques du moyen âge (Paris: Librairie Victor Lecoffre: J. Gabalda, 1908). In the preface to his “Little Roman Martyrology” (known to posterity as the Parvum Romanum), Ado claims as his source a very ancient martyrology, sent in former times by one of the popes to a bishop of Aquileia, which being lent to him during a visit to Ravenna, he hastily transcribed. The Parvum Romanum is in fact a bastardization of Florus’s work, with drastically altered dates and “the addition of details of all sorts, embellishments that seem to have been added to improve the story and to make his Martyrology outstanding and successful.” Sheppard, The Liturgical Books, 61. Although Ado has been vilified as a forger, at least one author is willing to give him the benefit of the doubt: “The Frankish cleric Ado was probably deceived by some wily Italian.” Frederick G. Holweck, A Biographical Dictionary of the Saints: With a General Introduction on Hagiology (St. Louis: B. Herder Book Co., 1924), x.

- Martyrologium Romanum ad novam kalendarii rationem et ecclesiasticæ historiæ veritatem restitutum Gregorii XIII iussu editum. The full title refers to the new Gregorian calendar adopted in 1582.

- From the Greek mēnologion (mēn, month + logos, account), a menology corresponds to the Latin martyrology.

- In 1586 the Martyrologium Romanum was republished under Sixtus V with annotations and a learned treatise by the Oratorian priest (later Cardinal) Cesare Baronio, the leading light of Gregory XIII’s commission. New typical editions appeared under Urban VIII (1630), Benedict XIV (1749), and St. Pius X (1914). The fourth edition post typicam (of 1914), published in 1956, is the last Vatican edition issued before the Second Vatican Council.

- The 1584 Martyrologium Romanum was itself an attempt to review and correct the martyrological tradition popularized by Usuard. In the 17th century a group of Belgian Jesuits known as the Bollandists (after Fr. Jean van Bolland, 1596-1665) began applying the then-new methods of historical criticism to hagiography, combing the lives of the saints to separate fact from fiction. (Their scientific approach was not without controversy. When, for example, they challenged the Carmelite Order’s claim to have been founded by the prophet Elijah, they attracted the attention of the Spanish Inquisition.) The Bollandists continued their research until the suppression of the Jesuits in 1773. With the Jesuits reconstituted in 1837, the work of the Bollandist Society continues to this day. A problem that had long baffled the hagiographers was the fact that in the sources the same saints often appeared on different days, or on the same day under different names. The publication in 1866 of a recently discovered Eastern general martyrology known as the Syriac (written in 411) furnished a key for interpreting the Hieronymian Martyrology, for the sake of reaching the authentic originals embedded in that great collection of source materials. Several names that occur as a pair or a group in the Syriac Martyrology are separated in the Hieronymian, sometimes even being entered on different days or as belonging to different places. Often an entry is repeated on the day before and/or the day after the right day (e.g., in the Syriac Martyrology we find on Jan. 30, “In the city of Antioch, Hippolytus”; in the Hieronymian he is commemorated on Jan. 29, 30 and 31). Other saints appear more than once on the same day, with variants (e.g., on May 23 the Syriac Martyrology gives, “In Lystra, Zoilus the confessor”; in the Hieronymian we find on the following day the threefold entry “In Istria Zoili,” “In Siria Zoeli,” and “Item Zoili Striae”). Owing to these and numerous other difficulties, the Hieronymian Martyrology had ceased to be regarded as a trustworthy authority by the 1870s. A few decades afterwards, Ado’s Parvum Romanum would be entirely discredited.

- Second Vatican Council, Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium (1963), no. 92/c.

- Martyrologium Romanum ex decreto Sacrosancti Œcumenici Concilii Vaticani II instauratum auctoritate Ioannis Pauli PP. II promulgatum, Editio altera (Vatican City: Typis Vaticanis, 2004). This edition corrects a number of typographical errors and includes the 117 people canonized or beatified since 2001, as well as many saints who had not been listed in the Martyrology but who are much venerated, especially in southern Italy. The official Italian translation was issued the same year. The International Commission on English in the Liturgy (ICEL) has been working for several years to prepare an English translation of the book, and in 2022 a first draft was distributed to its “member” conferences of bishops for review. Upon completion of the final draft, conferences can vote their approval, and with the confirmation of the Holy See it can be published.

- The lunar calendar dates from pre-agricultural times, while a solar calendar marking the seasons suited agricultural civilizations. Vestiges of older calendar systems were often taken up into newer systems. The Greek lunar cycle of 19 years instituted in 432 BC was superseded by the solar Julian calendar, which retained the 12 months derived from the lunar calendar but adjusted the number of days in each. Although the Julian calendar was adopted throughout the Roman Empire, the Romans continued to count the days of the month backward from the Kalends (or new moon), the Ides (full moon) and the Nones (first quarter) respectively. Before the seventh century BC, the Hebrew calendar began in the autumn and followed the agricultural year, yet the dates of significant festivals were ascertained by reference to lunar phases. A parallel development might be perceived in the Christian calendar, originally confined to a weekly celebration of the Resurrection on Sunday—a short rhythm of worship linked to a roughly lunar pattern. The gradual accrual of martyrs’ anniversaries and annual Incarnation-related feasts on fixed days (such as Epiphany and Christmas) illustrates the ascendancy of the solar year without the loss of lunar significance. In resolving the Quartodeciman controversy, which debated the legitimacy of aligning the date of Easter celebration with the Jewish Passover, the traditional lunar element was taken up into the by-then normative solar time structure.

- The addition of the year of death, or at least of the century in which the saint lived, is a significant innovation presented by the index in the new Martyrology.

- Here, for example, is the first entry (of seven) for January 23: “At Caesarea in Mauretania, the holy martyrs Severian and his wife Aquila, who were consumed by fire.”

- Each month contains three reference dates: the Kalends, Nones, and Ides. The Kalends is always the first day of the month. Nones and Ides are on the fifth and 13th except in March, May, July, and October, when they fall on the seventh and 15th. For example, on July 4 the Roman date (as styled since medieval times) is “Quarto Nonas Iulii” or “Four Days before the Nones of July.” (The Roman custom is to count inclusively, so July 4 is considered four days before July 7.)

- Perhaps too cautiously in some cases. An interesting example is that of St. Rosalia. The older version reads: “At Palermo, the finding of the body of St. Rosalia, virgin of that city. Miraculously discovered in the time of Pope Urban VIII, it delivered Sicily from the plague in the year of the Jubilee.” The new version deletes reference to the finding of her body (and therefore transfers the eulogy from July 15, the day of the supposed finding, to Sept. 4, the day she died), the epidemic, and the pope, and instead speaks only of an alleged solitary life: “At Palermo in Sicily, St. Rosalia, virgin, who on Mount Pellegrino is believed to have led a solitary life.”

- The old Martyrology lists two Valentines for Feb. 14: the first, a Roman priest whose story dates to around 270; the second, the bishop of Terni in Umbria, whose story takes place nearly 70 years later. Both gave heroic testimonies of faith, both performed miraculous healings, and both were beheaded on the Via Flaminia in Rome. In the new Martyrology for Feb. 14 we find only one Valentine and it is not clear to whom it refers: “At Rome on the Via Flaminia near the Milvian bridge, St. Valentine, martyr.” The martyr associated with St. Valentine’s Day is Valentine of Terni. The Benedictine Order, which maintained the Church of St. Valentine in Terni during the Middle Ages, spread the cult of Valentine’s Day in their monasteries in England and France. The tradition of his being patron saint of lovers originated in Geoffrey Chaucer’s poem “Parliament of Fowls” (ca. 1381), which tells of birds choosing their mates on “seynt Volantynys day.”

- St. Christopher, the patron of travelers, is said to have carried the Christ Child on his shoulders across a river. He was martyred in the third century in Lycia, a region of modern-day Turkey. Whereas the old Martyrology tells of his being beaten with rods, cast into fire (from which he was miraculously saved), pierced with arrows and finally beheaded, the new Martyrology reads simply: “In Lycia, St. Christopher, martyr.”

- Inseparable from the Roman Martyrology is the Roman Calendar, which indicates the date and rank of the celebrations in honor of the saints (optional or obligatory memorial; feast; solemnity). Many of the deletions made in the post-Vatican II reform of the Martyrology resulted from the publication of the Roman Calendar of 1969. In keeping with the Council’s emphasis on historical reliability, more than 300 saints (plus unknown companions) were removed from the Calendar. But this was not the only reason why saints disappeared. In establishing the new Roman Calendar it was the Church’s goal to include only those “saints of a truly universal importance” (Sacrosanctum Concilium, no. 111), leaving other saints to the particular calendars of a given nation, region, diocese or religious community. The fact that St. Valentine and St. Christopher “survived the cut” (as far as the Martyrology goes) serves as a good reminder that only a small fraction of saints commemorated daily by the Church are in the General Roman Calendar.

- Most notably, Job (May 10) and Jonah (Sept. 21), who are often considered to be Hebrew literary creations, retain their feasts.

- It is not always easy to draw the line between Catholic and non-Catholic saints. When the Churches of Rome and Constantinople “split” over liturgical and theological differences in 1054, the result was not the immediate formation of separate Catholic and Orthodox Churches. Intercommunion continued on a local level for many years, even after the Fourth Crusade and the brutal rupture of Latin-Byzantine communion in 1204. That some unity did exist is shown by the fact that 30 post-schism Russians are venerated as Catholic saints, one of whom, Abraham of Smolensk (d. 1222), was canonized by Pope Paul III in 1549.

- 482 were added during the pontificate of St. John Paul II alone (1978-2005). On a single day in 2013 Pope Francis canonized the 813 inhabitants of Otranto in southern Italy who were all beheaded on Aug. 14, 1480, for refusing to convert to Islam after the city had fallen to the Ottomans.

- Already the practice in some monasteries in the mid-eighth century, it was extended to the secular clergy by the Synod of Aachen of 817.

- Sacrosanctum Concilium, no. 89/d.

- Martyrologium Romanum (2004), Ordo Lectionis Martyrologii intra Liturgiam Horarum, no. 1: “In choro lectio fit de more ad Laudes matutinas, post orationem conclusivam Horæ” (p. 29). Alternatively, the reading may follow the concluding prayer of the Minor Hours of Terce, Sext, and None (no. 6).

- The tradition of reading the following day’s saints served as preparation for Vespers that evening, which began the new liturgical day and hence the observance of those saints. Historically all feasts of any rank (as opposed to vigils and ferial days) began with Vespers the previous evening; it was “Second” Vespers that was the oddity—a festal appendage made to extend Sunday and the higher ranked feasts into the next liturgical day by superseding the Vespers of the following day. The 1955 reform of the Roman Calendar and Breviary recast most liturgical days according to modern clock convention (midnight to midnight), removing the original (and once only) Vespers from all feasts except Sundays and Doubles of the first and second class. (The various liturgical ranks were reclassified in 1960 and again in 1969.)

- Because the Martyrology is never read during the Paschal Triduum, the notices for Easter Sunday are read on Easter Sunday and precede the reading of Easter Monday’s notices.

- (Without the usual invitation “Let us pray.”) The traditional collect (the only one in the old Martyrology) reads: “May holy Mary and all the Saints intercede for us with the Lord, that we may merit to be helped and saved by him who lives and reigns forever and ever.” The postconciliar edition has this and 36 alternative collects for use ad libitum.

- According to the rubrics for the Liturgy of the Hours, if Lauds or Vespers is led by an ordained minister, the blessing and dismissal follows the pattern used at Mass (“The Lord be with you,” and so on), and the minister dismisses the people with the words “Go in peace” (to which they respond, “Thanks be to God”). A layperson who presides in the absence of an ordained minister makes the Sign of the Cross while saying, “May the Lord bless us, protect us from evil, and bring us to everlasting life.” The new Martyrology does not make this distinction: the blessing “May the Lord bless us…” and the dismissal “Go in peace” are said whether or not the one who presides is ordained.

- The prayer Et fidelium animae (“And may the souls…”). This prayer is not part of the conclusion of any hour in the Liturgy of the Hours, nor is it in the traditional Martyrology. It is used in the daily capitular office of monastic origin—a set of prayers and readings (including the Martyrology) said in the “chapter room” of the monastery immediately after Prime.

- Except when a Solemnity occurs on a Sunday of Ordinary Time or a Sunday of Christmas, in which case the Solemnity is celebrated in place of the Sunday.

- Martyrologium Romanum (2004), Praenotanda, no. 30, citing the General Instruction of the Roman Missal, no. 355b, and the General Instruction of the Liturgy of the Hours, no. 244.

- The Christmas Proclamation from the Roman Martyrology is located in Appendix I of the third edition (2010) of The Roman Missal. According to the rubrics, this Proclamation may take place immediately before the beginning of Christmas Mass during the Night. It may also be proclaimed at Evening Prayer on Dec. 24, in which case “it follows the introduction and precedes the hymn,” or else in “the Office of Readings just before the Te Deum.” Proclamations for Christmas, Epiphany, and Easter (Chicago: Liturgy Training Publications, 2011), vi.