It wasn’t until my sophomore year in college that I began to take my Catholic faith seriously. I was quick to quit the Sunday observance as soon as I left home. But thanks to the prayers of parents and relatives, and to the faithful example of influential peers, I was steered back to the Church through the doors of the Newman Center at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln.

Not long after I became more active at the Newman Center, the pastor handed me a book called Theology and Sanity by Frank Sheed. Sheed was an Australian-born writer, apologist, and street-corner evangelist and, together with his wife Maisie Ward, he founded Sheed and Ward Publishing. But beyond his example of a faith-filled, orthodox layman, Sheed’s Theology and Sanity was just what a young Catholic in my situation needed.

The thesis of Theology and Sanity is that the truths of faith, if true, are as fundamental to a sound mind—a sane mind—as the truths of biology, chemistry, or physics. Each newly conceived human life has its own, unique genetic code at conception; water is comprised of two parts Hydrogen and one part Oxygen; objects fall at a rate of around 9.8 meters per second, squared; God created all things out of nothing. Each of these aforementioned facts are true, regardless of whether or not one is a biologist, chemist, physicist, or religious believer. Whatever one wishes to do with such truths, however one wishes to respond (or not) to them, is a secondary matter. But to be unaware of them is to be ignorant; to think these truths are other than they are is to be in error—the sign of an unhealthy mind—mens insana.

Liturgical truths are equally necessary for a healthy—and holy—mind. It is essential that we see the liturgy correctly if we wish to “equate the mind and the thing” (to paraphrase St. Thomas Aquinas’s definition of truth).

What, then, stands before your mind’s eye at Mass? Do you see the Paschal Sacrifice of Christ offered to the Father? Do you hear the angels sing? Do you feel the grace of the Holy Spirit pulsate through your veins (that is, the veins of the Mystical Body) as we become men of full stature? If not, then your mind may not be as healthy as it ought.

In the United States, much has been made about the 2019 Pew Study that purports to find that a mere 30 percent of Catholics see Christ in the Blessed Sacrament. Or, to put it another way, nearly 70 percent are not seeing what’s really there before their praying eyes. To regain a degree of liturgical sanity, it is imperative that Catholics are “led toward a new kind of seeing, in which their eyes are gradually opened from within to the point where they recognize him afresh and cry out ‘It is the Lord!’” (Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy, 120).

Two practical tasks demand our attention if we wish to acquire liturgical health: first, the priest and his ministers must celebrate the liturgy beautifully, faithfully, and authentically; second, the faithful must learn to see beneath the surface of the ritual’s sacramental signs and symbols to the reality—Christ—they contain.

To begin with, the priest-celebrant is tasked with celebrating the Church’s liturgy according to the Church’s mind. At his ordination, he is asked by the bishop: “Do you resolve to celebrate the mysteries of Christ reverently and faithfully according to the tradition of the Church, especially in the Sacrifice of the Eucharist and the Sacrament of Reconciliation, for the praise of God and the sanctification of the Christian people?” The Church, after all, is the Bride of Christ, born from his opened side upon the cross. She knows who he is, what he looks like, how he acts—she knows the truth about the Truth. And for centuries she has been cultivating sacramental rites that reveal and communicate her Bridegroom to the world.

To be sure, this Church has its human members and, consequently, human limitations: as long as human beings are involved in the advancement or restoration of the liturgy, their efforts will be marked with fallenness and finitude that struggle to express the inexpressible God. The common critique of the preconciliar liturgies, for example, claims that the rites obscured more than they revealed (“overlaid with whitewash” was how Pope Benedict XVI put it). The Second Vatican Council desired to restore ritual elements that had fallen by the wayside over the years, to eliminate unnecessary duplications, and to simplify needlessly complex components. Yet the restored missal, too, is not without its critics: the loss of liturgical symbolism has oftentimes left a liturgy cold, didactic, and lacking in mystery. But these larger matters of reform are for the most part out of the control of most priests. What is in the priest’s power is his ability—indeed, his obligation—to celebrate the rites as given, for through these sacred celebrations, Christ will appear in our midst.

The faithful play the second key part in recovering liturgical sanity, for even when the priest does celebrate the rite as flawlessly as is humanly possible, the ritual demands that those at prayer see clearly and insightfully the Christ made present in sacred signs. That is, the liturgical disease may not be with the priest and the ritual, but with me. How can I come to see the Paschal Mystery in the Mass? Or discern the Body of Christ under the signs of bread? Or hear the Word of the Trinity in the words of the liturgy?

The prescription for the faithful’s shortcomings on this score is “mystagogical catechesis,” which “initiate[s] people into the mystery of Christ by proceeding from the visible to the invisible, from the sign to the thing signified, from the ‘sacraments’ to the ‘mysteries’” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1075). A central component of mystagogy uncovers a sacramental sign’s meaning (which is ultimately Christ) by examining its sources. For example, a mystagogical look at something as simple as a church’s front door would consider the cherubim who guarded the door to the Garden of Eden and the Tree of Life (Genesis 3:24), the door marked with the blood of the lamb at that first Passover in Egypt (Exodus 12:7), the doors of pearl through which the saved pass into heaven (Revelation 21:21)—and how each of these shows that the building’s door is none other than Christ himself, “the door” (John 10:9). Ah, yes—now I see!

Regaining one’s liturgical sanity, then, is within our grasp. It requires that our priests “celebrate the mysteries of Christ faithfully and reverently according to the tradition of the Church,” as they promised at their ordination. It also requires that the faithful do the “spiritual therapy” necessary to bring their sacramental senses back to health and be “led toward that new kind of seeing.” Let us not misdiagnose the causes of today’s liturgical insanity. It does not lie—or at least does not principally lie—with Councils, Consiliums, or Commissions, nor with clerics high and low. Rather, it lies with—and within—each of us at the liturgy.

In one of the opening paragraphs of Theology and Sanity, Sheed understands that true sanity is found in looking with the eyes of the Church. While it’s true that he was speaking about more than the liturgy, his words still apply here: “Seeing what [the Church] sees means seeing what is there. And just as loving what is good is sanctity, or the health of the will, so seeing what is there is sanity, or the health of the intellect.”

While consuming too much cantankerous commentary can make one lose one’s mind, a healthy diet of authentic liturgy, celebrated after the mind of the Church, and engaged with intelligence and docility will always be a prescription for not only, as Sheed says, intellectual health, but also and ultimately, for spiritual health.

Christopher Carstens is director of the Office for Sacred Worship in the Diocese of La Crosse, Wisconsin; a visiting faculty member at the Liturgical Institute at the University of St. Mary of the Lake in Mundelein, Illinois; editor of the Adoremus Bulletin; and one of the voices on The Liturgy Guys podcast. He is author of A Devotional Journey into the Mass and A Devotional Journey into the Easter Mystery (Sophia), as well as Principles of Sacred Liturgy: Forming a Sacramental Vision (Hillenbrand Books). He lives in Soldiers Grove, Wisconsin, with his wife and children.

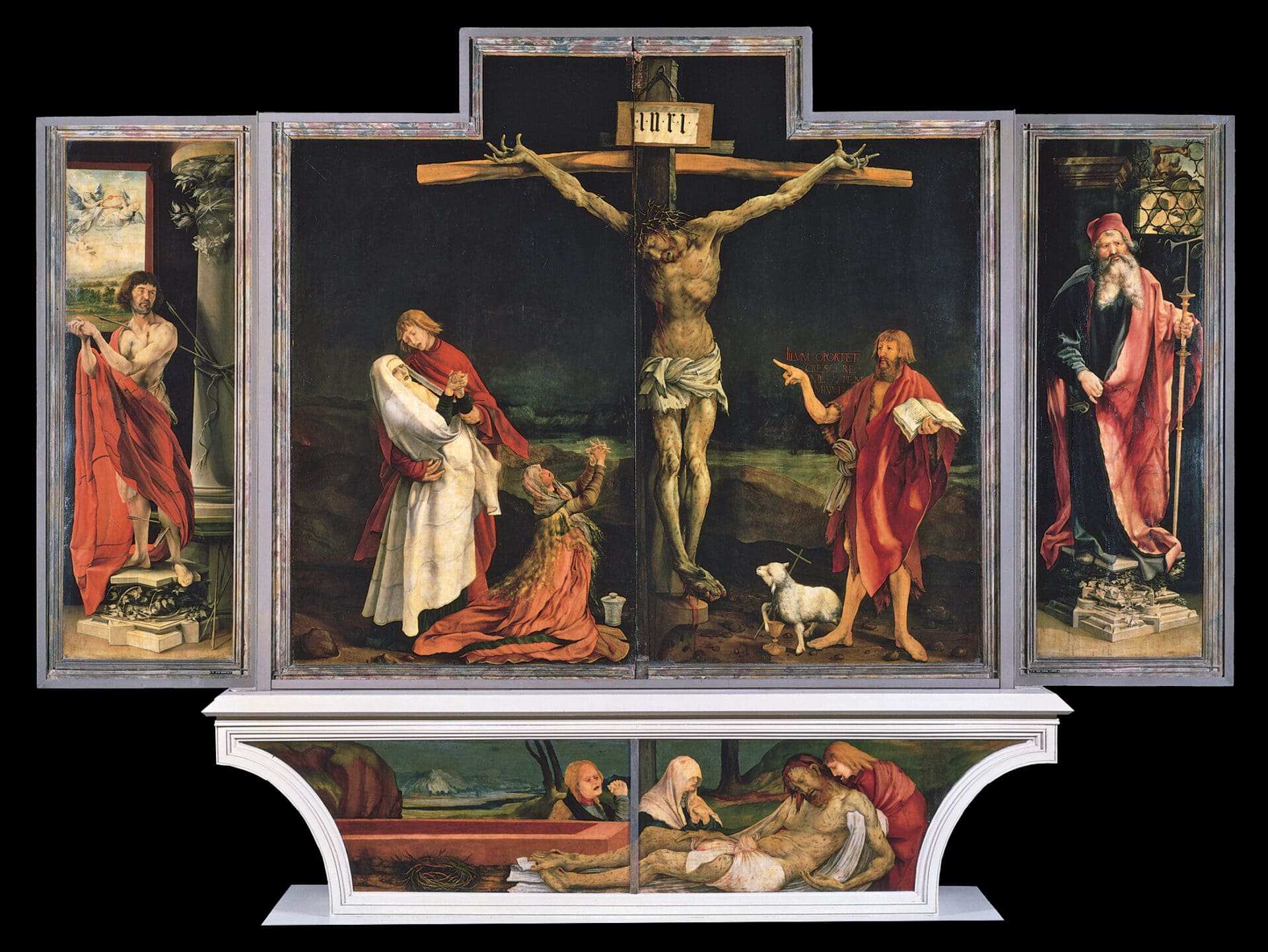

Image Source: AB/WikiArt. The Resurrection of Christ (right wing of the Isenheim Altarpiece, c.1512 – c.1516), by Matthias Grünewald