Christmas celebrates the Incarnation of the Son of God. And while this truth is obvious even to the youngest child, it is perhaps less apparent just how God becoming man applies to the celebration of the sacred liturgy. Fortunately, Christians today are beneficiaries of the wisdom which our forefathers accumulated in their struggle to understand how the Second Person of the Trinity could take on a human nature.

After the Council of Nicaea determined definitively that Christ was God, rejecting Arius’ claim that Christ was simply the highest of God’s creatures, bishops and theologians still sought to articulate the “mechanics” of the Incarnation: was Jesus half-God and half-man? Or was he a God inhabiting a human guise? Or a God-man mixture that was a third kind of being altogether? In fact, there were numerous theories put forth to try to understand the truth of the matter.

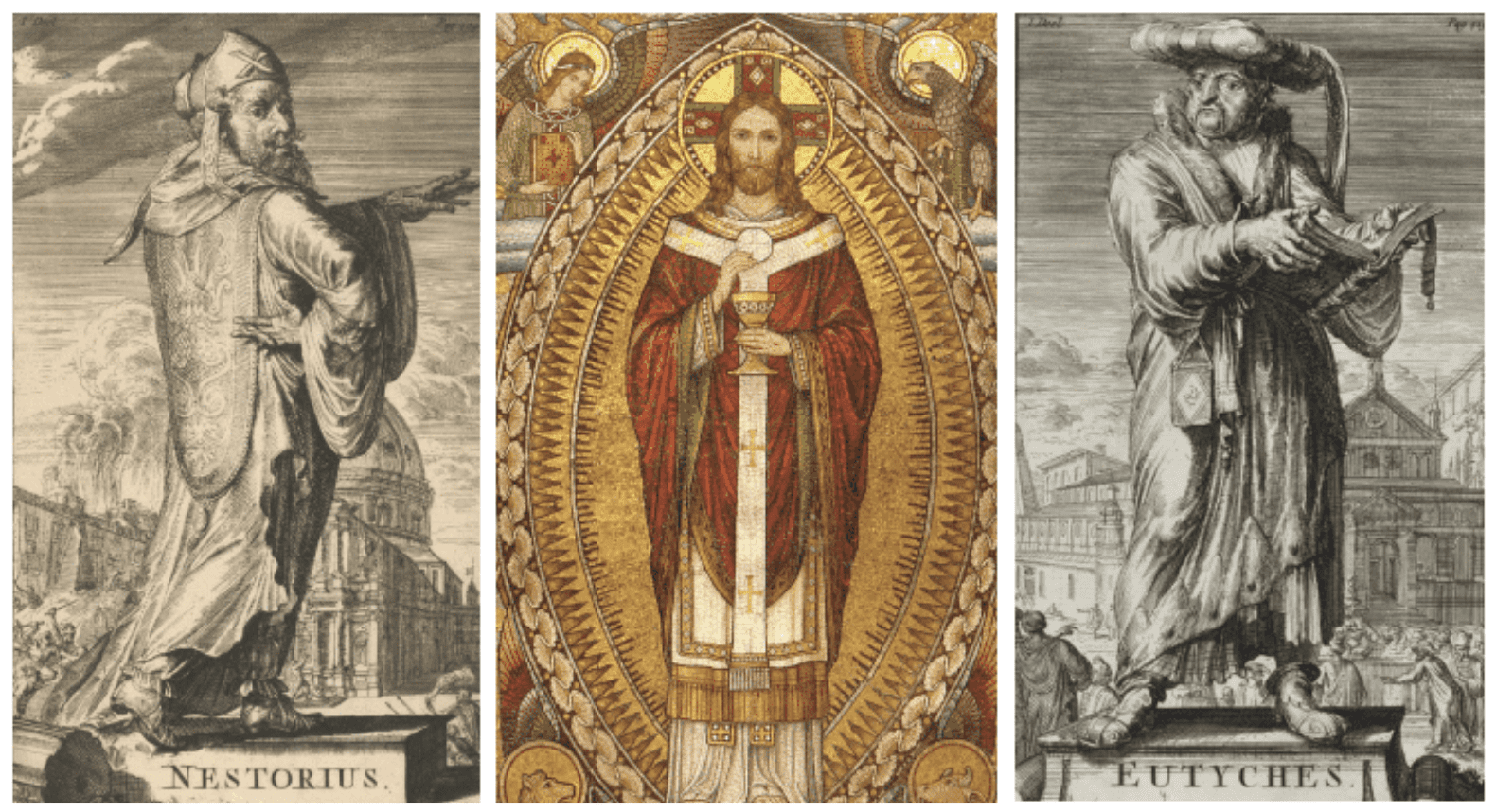

A significant step forward came at the Council of Ephesus in 431, and at the expense of Nestorius, the Archbishop of Constantinople, who put forth the idea that the incarnate Christ was, in essence, both a human person and a divine person, as well as possessing a human nature and a divine nature. (At the risk of oversimplifying this distinction, “person” describes who one is; nature describes what a thing is—e.g. Who am I? Christopher Carstens. What am I? A human being). Consequently, Nestorius said, Mary was not the mother of the divine person (she was not Theotokos) but of the human person simply. In response, however, the Council taught that Jesus is not “two persons,” but one: the Second Person of the Holy Trinity—and Mary was his mother. In a certain sense, the now-notorious Nestorius was emphasizing and even safeguarding the human dimension in the incarnate Christ, although (unfortunately for Nestorius) at the expense of our Lord’s divinity.

Another fine-tuning of our understanding of the Incarnation came 20 years later at the Council of Chalcedon in 451. Here, the priest and monk Eutyches took the issue to the other extreme, claiming that in Christ the human nature “morphed” and mixed with the divine nature. This monophysitism, as it came to be called, was rooted in a kind of skepticism of things created and human. Hence the human nature of the incarnate Christ had to give way and change into something greater, namely, divinity. The heresy of monophysitism, then, while emphasizing the divinity of the incarnate Christ (which is good), downplayed and even denied the humanity of Christ (which, for Eutychus, is bad).

So, what is the proper understanding of God-become-man? What is (in the words of priest and liturgical theologian Louis Bouyer) the “Law of the Incarnation” that we have been blessed to inherit? It is that the incarnate Christ is one divine person—God the Son—with two complete and unmixed natures—human and divine.

Whew! We should be grateful that we ourselves didn’t have to struggle to come to such an understanding but have it given to us by the Church. Still, there’s an ever-present hazard that we could break this Law of the Incarnation when we celebrate the sacred liturgy. That is, just as errors have occurred in our understanding of the Incarnation by either denying aspects of Christ’s divinity or eclipsing elements of his humanity, so the liturgy can do the same. This should not surprise us: while Christ is present in numerous ways in the Church and the world today, it is the liturgy (and especially the Mass) that manifests his presence—one divine person in two united yet distinct natures—most perfectly.

What does a Monophysite Mass look like? Just as Eutyches et al saw in the incarnate Christ a transcending of the human element, a Monophysite-tending liturgy may put up a “wall of Latinity” (to use Pope Benedict XVI’s phrase) that is a barrier for most modern men and women. Bouyer himself mentions a “rubricist mentality” that at times treats liturgical norms as if they themselves were delivered directly by God and, on the whole, don’t allow for any adaptation to the needs of modern men and women. The idea of the liturgical mystery is often misunderstood by this mindset as an impenetrable secret rather than the plan of God’s mind revealed in time to save all things in Christ—a plan to be known, celebrated, and proclaimed to all. As Bouyer summarizes, “all that could make the liturgy a living thing, all that would help the people to share in it, is considered a profanity—as if the liturgy could only retain its sacred character by being removed from any contact with the common man” (Rite and Man, 6).

In contrast, a Nestorian-leaning liturgy, like its unfortunate namesake, errs on the other extreme by emphasizing the humanness of the Mass and sacraments at the expense of the divine. How? Chalices and patens become everyday cups and plates. Presidential style ceases to differ in any way from the mannerisms of the average man on the street. Music and architecture cease to distinguish themselves from popular forms of art. Even the smallest amount of Latin is not allowed (a “wall of vernacularity”?), often by (wrongly) invoking the Second Vatican Council. And being in church is no different from being at home, at school, or at work. “According to the Nestorian concept,” concludes Bouyer, “everything about the Mass should recall a profane meal, even to the inclusion of mundane conversations” (Rite and Man, 9).

Bouyer applied this “Law of the Incarnation” in his 1963 classic Rite and Man (recently republished by Cluny Media). He and others had in mind a Monophysite-trending liturgy of 1923. But he must have experienced a sort of spiritual whiplash when he witnessed the Nestorian-trending celebrations of 1973.

But how would Bouyer—and how would you—describe our liturgies of 2023? Are they mundane activities that downplay their divine origin? (And isn’t this a significant reason why the preconciliar liturgy has gained popularity over the last decades?) Or are they foreign affairs that don’t nourish us and appear to have little to no bearing on human life? Or—ideally—are they soundly orthodox, following faithfully the Law of the Incarnation, revealing as fully as possible the transcendent divinity of Christ through fully human forms?

While we still bask in the incarnate light that has entered our darkness, and as we consider what New Year’s resolutions are worth continuing, let us take an honest look at our liturgies. For the Incarnation—in Christ and his liturgy—is not just a good idea: it’s the law.

Christopher Carstens is director of the Office for Sacred Worship in the Diocese of La Crosse, Wisconsin; a visiting faculty member at the Liturgical Institute at the University of St. Mary of the Lake in Mundelein, Illinois; editor of the Adoremus Bulletin; and one of the voices on The Liturgy Guys podcast. He is author of A Devotional Journey into the Mass and A Devotional Journey into the Easter Mystery (Sophia), as well as Principles of Sacred Liturgy: Forming a Sacramental Vision (Hillenbrand Books). He lives in Soldiers Grove, Wisconsin, with his wife and eight children.

Image Source: AB/Wikimedia (Nestorius and Eutyches)/Christ as the High Priest mosaic, Adoration Chapel, Benedictine Sisters of Perpetual Adoration; Photo by Sister Sean Douglas, OSB.