When Alexander the Great made his way through Palestine in the 4th century BC, he left behind key features of Hellenistic culture. Chief among these was the Koine dialect of the Greek language, which became the language of the New Testament.

Consequently, not only a great many secular words today, but a large number of ecclesial words (such as “ecclesial”) are Greek in origin: episcopate and diaconate, baptism and eucharist, evangelization and martyrdom. The word “liturgy” is also Greek (leitrougias), indicating a work (ergon) that is done on behalf of the people (laos), as is a term for one of the liturgy’s most essential concepts: symbol.

“Symbol” is built on the root ballein, which means to throw, hurl, or toss. Ballein is the root of today’s English word “ballistics.”

A “parable” is similarly structured on this root ballein, and it means “to throw (ballein) alongside (para),” as when Jesus tells a story that illustrates—but does not come out explicitly and state—a truth of faith. The “Parable of the Sower,” for example, speaks of the various types of soil (that is, souls) that receive the Word of God. Only after the parable has been told do the disciples ask him its core meaning (see Luke 8:1-15).

“Hyperbole” indicates an exaggerated way of speaking: “The Adoremus Bulletin is the best liturgical journal ever!” Literally, hyperbole means “to throw (ballein) up (hyper).”

An “embolism” is an obstruction that has been “thrown (ballein) into (em)” the heart or artery. Less painfully—in fact, more helpfully—the priest “throws in” a special prayer or elaboration after the Lord’s Prayer and before its conclusion at Mass, when he says, “Deliver us, Lord, we pray, from every evil, graciously grant peace in our days…”—thus, this heart-felt prayer is also called an embolism.

Even evil throws its weight around. “The devil (dia-bolos) is the one who ‘throws himself across’ God’s plan and his work of salvation accomplished in Christ” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2851).

But let’s now throw ourselves back together with the term “symbol.” The liturgy, the Catechism teaches, “is woven together from signs and symbols” (1145). Every ritual is a tapestry of symbols—objects, actions, words, ministers and people, times, music, art, and architecture. Think, for example, of the Introductory Rites of the Mass, or the baptism of an infant, or the celebration of Vespers. In each and every case, the ordered use of symbols “throw together.” But throw together exactly what?

In the beginning, when God made the cosmos (which is an another Greek term, meaning order and beauty), heaven was united to earth, God walked together with man, and all lived together in unity and peace. But with sin—enter the diabolic one—cosmos turned to chaos: creation separated from heaven, man hid himself from God, and the fallen world came to disorder. What was needed to undo the separation and restore unity was a great Symbolizer—indeed, a super-symbolizer: a sacramentalizer—who could throw heaven and earth, God and man, and all of creation together again. This is the incarnate Christ.

His work of rejoining heaven and earth, however perfect, is as of yet incomplete. In God’s grand plan, we are called to join him in joining earth to heaven once again. And the greatest means by which this saving and sanctifying work is accomplished is in the liturgy and sacraments. Woven “from signs and symbols,” liturgical celebrations restore us to God.

Much rides, then, on getting sacramental signs and symbols right. And by getting them right, I mean both representing fully and clearly the divine realities they signify, and also allowing us fallen beings to engage them and reunite ourselves through them, and Christ, to God. Most liturgical debates can be reduced to this basic level: do the various ritual symbols—words, music, gestures—bring together heaven and earth? Or, perhaps, are they “lopsided” (not a Greek word, by the way), by not revealing the mystery as fully and authentically as they might, or, for a variety of reasons, by thwarting our encounter with the mystery?

The seriousness of liturgical symbolism was a large part of what Sacrosanctum Concilium addressed in its reforms. Pope John XXIII first laid some founding principles when he opened the Council on October 11, 1962: “The substance of the ancient doctrine of the deposit of faith is one thing, and the way in which it is presented is another” (emphasis added). In liturgical terms, the divine reality of the liturgy—the saving work of Christ—remains an unchanging reality for all ages, yet the manner in which it is symbolized requires that it be adapted, when possible, to the conditions of those who celebrate.

Sacrosanctum Concilium would say as much when it established norms for the reform and restoration of the liturgy’s sacramental signs: “That sound tradition may be retained, and yet the way remain open to legitimate progress…” (22). And again: liturgical signs and rites “are to be simplified, due care being taken to preserve their substance” (50). Yet, even while liturgical signs and symbols “preserve their substance,” they should radiate with “a noble simplicity; they should be short, clear, and unencumbered by useless repetitions; they should be within the people’s powers of comprehension, and normally should not require much explanation” (34). To rejoin heaven and earth—to symbolize—sacramental symbols must be both heavenly and earthly.

Prior to the Council, a common complaint about liturgical symbolism claimed that its expression of the mystery was “overlaid with whitewash” (Benedict XVI, The Spirit of the Liturgy, preface) and that it needed to be “purified of the imperfections brought by time, newly resplendent with dignity and fitting order” (Pius X, Motu proprio Abhinc Duos Annos, 1913). Postconciliar reforms certainly “laid bare” (Pope Benedict XVI) the essentials, but in so doing stripped away much that was meaningful, leaving a symbol system too didactic and lacking beauty.

So we still work today to understand, celebrate, and appreciate the liturgy’s symbols. Far from obscure, yet never anemic, liturgical symbolism ought to radiate the glory of God to eyes and ears willing and able to see and hear. When we can hit upon such a formula, we are truly reunited to God.

The Blessed Virgin Mary, following the remarkable events of her Son’s conception and birth, “kept all these things, reflecting on them in her heart” (Luke 2:19). Writing in Greek, Luke the Evangelist said more than “reflecting,” but, rather, “symbolizing” (symballousa) these things in her heart, fitting them together into a whole that kept her in union with God’s plan. May she pray for us now as we pray for citizenship in the Heavenly Jerusalem.

Christopher Carstens is director of the Office for Sacred Worship in the Diocese of La Crosse, Wisconsin; a visiting faculty member at the Liturgical Institute at the University of St. Mary of the Lake in Mundelein, Illinois; editor of the Adoremus Bulletin; and one of the voices on The Liturgy Guys podcast. He is author of A Devotional Journey into the Mass and A Devotional Journey into the Easter Mystery (Sophia), as well as Principles of Sacred Liturgy: Forming a Sacramental Vision (Hillenbrand Books). He lives in Soldiers Grove, Wisconsin, with his wife and eight children.

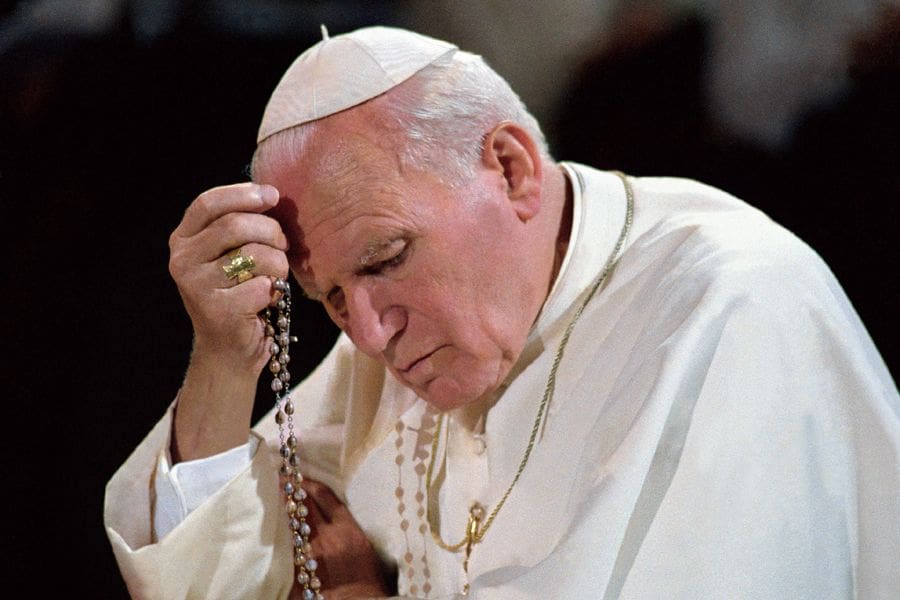

Image Source: AB/Lawrence OP on Flickr