There had been talk of an ecumenical council of the Catholic Church well before 1962. Indeed, Pope Pius XII had begun preparing for one after World War II, though he thought the spirit of age was becoming too relativistic to have a proper council free from bias at the time. Why did people feel they needed another council? After all, even at its conclusion, Pope Paul VI was clear there were no new doctrines taught in Vatican II nor new errors answered.

There were several pastoral reasons why people thought a council was important. First, Vatican I had been called to update the Church for a new missionary era and to free the Church from the influence of the state, which dated back to Roman Emperor Constantine in the fourth century. Though the influence of the Christian state had been helpful for centuries, during the Enlightenment, the state began to usurp the freedom of the Church through new errors like Gallicanism, which tried bringing control of the local Church under the state, not Rome.

Vatican I finally proclaimed the freedom of the Church from the state in 1870 with the doctrine of papal infallibility. However, the bishops had wanted to discuss 50 topics, known as schema, but because of the emergency dissolution of the Council due to the political situation of the military occupation of Rome by the emerging Italian state, the Council was left unfinished.

In a nascent form, the much-emphasized concepts of ressourcement (return to the sources) and aggiornamento (updating) were already at work. Though these were later enshrined in the study of the Fathers of the Church and Holy Scripture, one can see concern for these two concepts had already begun in the founding of the Leonine Commission by Pope Leo XIII to make critical editions of the complete works of St. Thomas Aquinas. Vernacular in the Roman liturgy, the laity, the nature of the Church and other topics were also slated for discussion to serve a Church that had added millions of converts from non-European countries since the Council of Trent (1545-1563).

The political situation of two world wars and the fall of dynasties did not allow for a time of economic peace in Europe until the 1960s for the possible continuance of Vatican I. Pope John XXIII therefore called the Council for the renewal of the spiritual life. This was to serve as the basis for the Christian renewal of the supernatural order in the face of a Church that had become excessively bureaucratic. With an emphasis on grace and mercy, the Second Vatican Council was to not change the doctrine of the faith but to make it more accessible to the modern mind.

This renewal of theology would entail revisiting the theological status quo established in the 19th century, which had been founded on a return to the thought of Thomas Aquinas. The trouble was that this return was dominated by theological manuals that often did violence to the texts they were meant to summarize and comment on.

New initiatives on historical criticism were being applied in sacred Scripture, and the new liturgical movements were also seeking some simplification and return to the sources of worship, especially the breviary. The attempt to be free from control of the civil state had a new urgency because of the totalitarian state at that time primarily represented by the Iron Curtain behind whose atheism millions were denied freedom of worship. New questions regarding morality also demanded an authoritative answer.

Vatican II had a long period of preparation, and though it was in some sense a continuation of Vatican I, Pope St. John XXIII formally closed Vatican I just before the beginning of Vatican II so there could be no doubt that the new Council sought a true self-examination on the part of the Church. Ecclesia, quid dicis de te ipsa? (“Church, what do you have to say about yourself?”).

Before John Paul II became pope, he wrote a book, The Sources of Renewal, on the proper understanding of Vatican II. According to him, this question is the key to understanding the Council. Chapter 4 is entitled, “The Consciousness of the Church as the Main Foundation of Conciliar Initiation.”

As a bishop who was present at the Council, imbued with the trust and teaching of Vatican II, he pointed out that the whole conciliar project can only be understood as a great self-examination on the part of the Church. He said, “It is impossible to treat the Church merely as an ‘object’; it had to be a ‘subject’ also. This was certainly the intention behind the Council’s first question: ‘Ecclesia, quid dicis de te ipsa?’”

There have been many books written on the teachings of the Second Vatican Council. The two principal documents are the dogmatic constitutions that form the interpretive bases for all the rest: De Ecclesia (The Church), also known by the first two words, Lumen Gentium (The Light of the Nations) on the Church, and Dei Verbum (The Word of God) on divine Revelation.

Pope St. John Paul II looked on Vatican II as the natural completion of a long theological clarification on the part of the Church that began in the Council of Nicaea with the nature of God the Father and God the Son. For him, this development was clarification of the Trinity, then the sacraments, and finally the Church vis-à-vis the state. Revelation is the important basis for them all and the basic truth which the Council was called to present.

This is evident for these foundational constitutions. Both are emphatic about the supernatural character of the Church, which demands affirmation of revelation with two equal sources: Scripture, which is divine Revelation written, and Tradition, which is divine Revelation preached.

Questions of authority regarding the magisterium or teaching authority of the Church are secondary because the magisterium is not a source of Revelation but the servant of Revelation. It thus serves the truth and is not its origin. All the other documents line up behind this.

Dignitatis Humanae, about the freedom of conscience in relation to religion, is not an affirmation of indifferentism, which teaches that all religions are equally true. It is the recognition that faith cannot be determined by the state and that one must come to the act of faith as a result of a free choice of the will unencumbered by external coercion.

The other documents that implemented the general principles were pastoral in intention. These included the laity (Apostolicam Actuositatem); renewed emphasis on the bishops as successors of the apostles (Christus Dominus); a priestly service and seminary training that emphasized truth and emotional maturity (Prebyteroroum Ordinis and Optatam Totius); return to the spiritual character of religious rules (Perfectae Caritatis) and an ecumenism that sought common ground (Unitatis Reintegratio).

An important practical implementation of the intention of Vatican II was to recover the ancient liturgy of the Church and to open this treasure to those cultures where Latin was perhaps a great challenge. So, in Sacrosanctum Concilium, the Fathers called for a renewal of the Sacred Liturgy, which would emphasize both its supernatural purpose and broad appeal beyond cultures.

Important steps had already been taken before the Council was called in the budding liturgical movement. There was a final addition called Schema XIII, which eventually became Gaudium et Spes, the pastoral constitution on the Church in the modern world.

Though this is often considered the most liberal document of the Council, two things should be noted. Some of the considerations of the modern world that were true in 1965 are not true in 2022 because the religious nature of the culture has changed dramatically. Also, a very central concern that remains true is the defense of the human person as an object of love and sincere gift, especially in relation to marriage. This document is a testimony to the dignity of the person and includes a deep and beautiful explanation of original sin.

Though this Council was indeed an event that the Holy Spirit directed in the life of the Church, the implementation of the documents was a problem even while the Council was going on. Because the spirit of the age was so critical of absolute objective truths in the 1960s, before the documents were finally approved and the bishops could present them, self-proclaimed experts had already muddied the waters with subjectivism, a condition that exists today.

Immediately before the extraordinary synod that produced the Catechism of the Catholic Church and celebrated the 20th anniversary of the closing of the Council in 1986, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger gave a now-famous interview, which became The Ratzinger Report, in which he expressed the frustration of the whole Church about this Council.

For the first time, an authority openly stated that what was being taught and done in the Church in daily practice did not fulfill the intention of Pope John XXIII in calling the Council: “What is certain is that the Council did not take the turn that John XXIII had expected. […] It must also be admitted that, in respect to the whole Church, the prayer of Pope John that the Council signify a new leap forward for the Church, to renewed life and unity, has not — at least as yet — been granted.”

It seems that no one is really satisfied with what has been happening in the Church since Vatican II. For some, it went too far. For others, it has not gone far enough.

What is certain, though, is that very few people really have a clue as to the actual teaching in the documents because very few have actually read and studied them. This has allowed a strange interpretation to develop, especially in universities and seminaries, that evokes a mythical “spirit of the Council” to justify departure from the real text of the Council.

Cardinal Ratzinger defines it thus in The Ratzinger Report:

“Already during its sessions, and then increasingly in the subsequent period, was opposed a self-styled ‘spirit of the Council’, which in reality is a true ‘anti-spirit’ of the Council. According to this pernicious anti-spirit [Konzils-Ungeistin German], everything that is ‘new’ … is always and in every case better than what has been or what is.”

The famous conciliar theologian Cardinal Henri de Lubac, noted a similar difficulty in the reading of the documents. A peritus (theological expert) at the Council, he called it the “para-council”:

“Just as the Second Vatican Council received from a number of theologians instructions about various points of the task it should assume, under pain of ‘disappointing the world,’ so too the ‘post-conciliar’ Church was immediately and from all sides assailed with summons to get in step, not with what the Council had actually said, but with what it should have said. […] This is the phenomenon which we should like to designate as the ‘para-Council.’”

This “para-Council” has basically altered what the Fathers at Vatican II specifically taught on many subjects.

As de Lubac has so astutely noted, “What the para-Council and its main activists wanted and demanded was a mutation: a difference not of degree but of nature. For this reason the renewal contemplated by both the Pope and the Fathers has been postponed.”

“Vatican II remains a project bravely begun but as yet partially unfilled. It is to be hoped that, when freed from the relativism of the ’60s, another verse much beloved of Pope St. John XXIII will finally be fully realized: ‘For this is the will of God, your sanctification’” (1 Thessalonians 4:3).

Dominican Father Brian Mullady is a member of the Province of the Most Holy Name of Jesus in Oakland, California. A frequent guest and host on EWTN, he is the author of Light of the Nations, which looks at the relevance of the documents of Vatican II to the Church today.

This article originally appeared here at the National Catholic Register and is reposted here with permission.

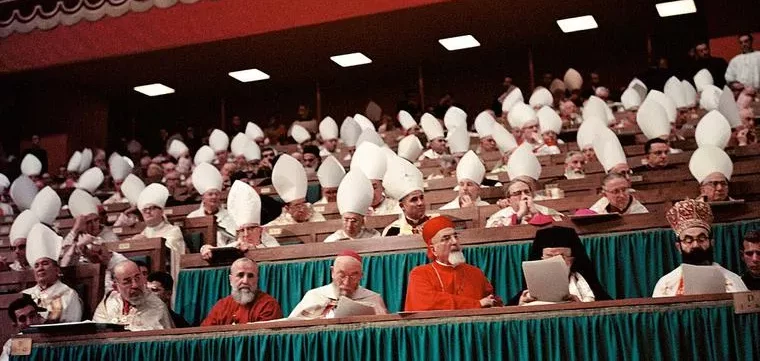

Image Source: Lothar Wolleh / Public Domain