Q: How is an altar initiated according to the rites of the Church?

A: If we have paid attention in Catholic school or catechism class, we know that our reflection of the Redeemer returns and grows through the sacraments of initiation—Baptism, Confirmation, and the Eucharist. Those who regain the lost image of God most perfectly are called saints. What we may not know is that the fallen, material world is similarly restored through a kind of Baptism, Confirmation, and Eucharist. A particularly substantial ritual that celebrates nature’s divine restoration is the Order for the Dedication of an Altar.

Before an altar comes to life as a divine image of Christ, it is as mundane as any other table. So when the diocesan bishop—who is the ordinary minister of adult initiation—arrives, he ignores the “altar” and walks immediately to his chair during the entrance procession. After all, if the soon-to-be-but-not-quite-yet-initiated altar is at this point not significantly different from any other table, why would he bow to it or kiss it? In fact, at this, the beginning of the ritual, the altar stands naked: no cloths, no candles, no flowers adorning it.

But then a remarkable thing happens: the bishop blesses holy water, and then he sprinkles it on the people (whose hearts, the Rite says, are the true “altar of God”) and the altar. Much as that first creation emerged from the waters (Genesis 1:1)—and not unlike our own rebirth from the baptismal font—the altar begins its supernatural genesis from water.

After the sprinkling of holy water during the Mass’s introductory rites, the Liturgy of the Word follows. But this doesn’t mean that the altar is now fully initiated. Like God’s people, whom the altar represents, the altar’s baptism is next “confirmed” with sacred chrism. The bishop goes to the altar and pours chrism on the four corners and center of the altar’s top, evoking the five wounds of Christ, whose image the altar is becoming. The bishop then anoints with his hand the entire altar top.

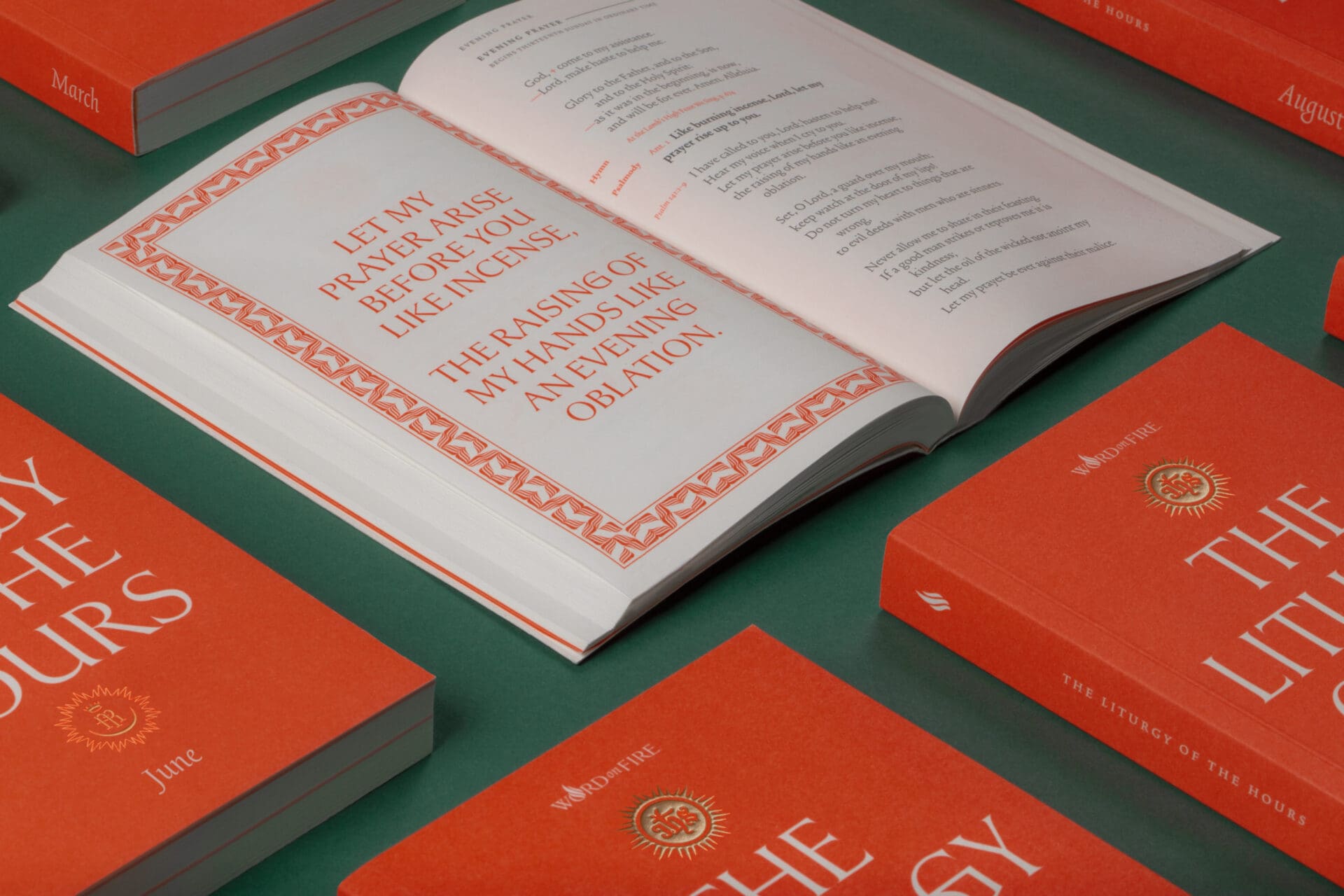

A few additional rites are necessary before the altar’s initiation is complete. First, the chrism is wiped from the altar—removed along with the incense that was also burned upon it, signifying how our “prayers rise like incense” (Psalm 141:2) before God. Washed clean with water and confirmed with sacred chrism, the altar is now covered with a white cloth (other colors are not permitted), much as the newly-baptized member of the Church dons an alb (from the Latin albus, “white”). Second, like the newly-vested neophyte who receives a lit baptismal candle, the altar’s candles are solemnly lit for the first time. Finally, the bishop performs that gesture he had omitted at the start of the Mass—he approaches the altar and kisses it, signaling that it is becoming the presence of Jesus.

But as significant as these elements are—the vesting, the lighting, and the kissing—the most important rite for the altar now begins: the celebration of the Eucharist. Here, again, we witness a remarkable parallel between the initiation of a person and the “initiation” of an altar: both complete their sacramental conformity to Christ in the reception of their first Holy Communion. When referring to the altar, the Order for the Dedication of an Altar cites St. John Chrysostom on the point: “This altar is an object of wonder: by nature it is stone, but it is made holy after it receives the Body of Christ.” There exists no greater transformative force on earth than the Eucharist, for it has the power to change any worthy recipient—be it a person or an altar—into Christ.

Men and women become saints by actualizing in the world their reception of Baptism, Confirmation, and the Eucharist. Tables become altars by a similar sprinkling with holy water, anointing with sacred chrism, and receiving and giving the Eucharistic Christ.

—Answered by the Editors