In the upper room on Holy Thursday, the truth incarnate entrusts and conveys himself wholly to his apostles for the purpose of drawing all men to himself. This total self gift is offered by way of a mimetic commission: “that you should do as I have done to you” (John 13:16). There is a word for this re-communicable handing on of the real: “tradition.” But this word’s Latin cognate, tradere, carries a distinctively paradoxical double meaning: it can be translated as “to hand on” as well as…“to hand over.”

The acts of tradition and betrayal, then, are virtually identical in external appearance. To most, the sordid deeds of Judas are completely invisible: “Now no one at the table knew….” Astonishingly, his brothers will even praise him in the midst of his treachery “that he should give something to the poor” (John 13:28).

This episcopal ambivalence to treachery might resonate sorrowfully with many faithful of today. But how exactly is a Catholic to respond to apostolic betrayal? A glance at the Catholic blogosphere indicates that scandalous deeds have an all-too-common consequence: the scandalization of Catholics—literally, we stumble. Being scandalized takes many forms. We run away, we become “outraged,” we lose faith, we lose hope; ultimately, we can end up scandalizing others in return, entering into the anti-tradition that is but a repeatable mirror of Judas’ own “going out” (John 13:30). Whether or not these echoes of Judas’ betrayal today are wounding the mystical body to an extent without historical precedent is not the subject of this article. But just as the act of apostolic tradition has been echoed—repeated to today for the good of the Church—and will be until Christ returns, so too, it seems, shall the act of betrayal be echoed. And woe to him who cooperates in this betrayal. Tradition, which characterizes the apostolic charism, is mimicked and doubled through demonic parody—seeding the anti-charism of apostolic betrayal. Every apostle in that upper room receives an invitation to hand on; one chooses to hand over. As a Church, perhaps now more than ever, we must learn how to respond to this betrayal. If we think we can easily spot the difference between either sort of tradere, we are surely deluding ourselves. Even in that upper room, after all, right up to the end, Judas had managed to dupe every apostle—every apostle but one.

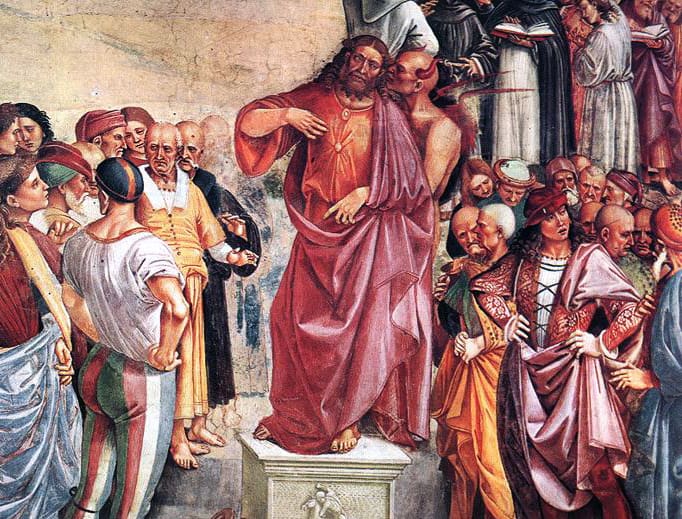

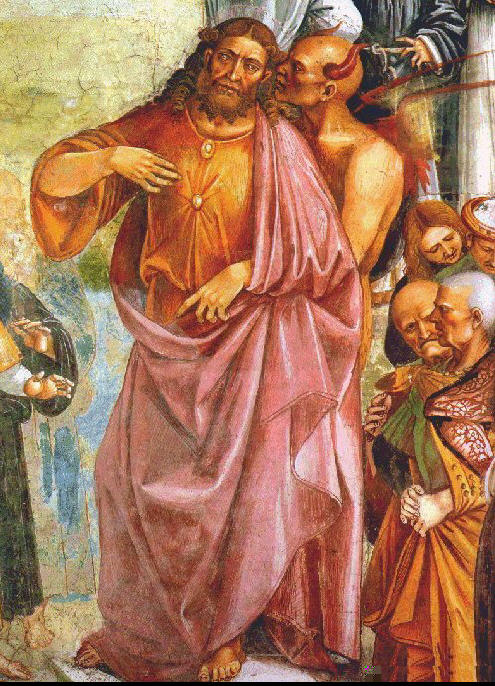

The Beast and the Lamb

In St. John’s Revelation we view the apocalyptic battle between two figures: the beast and the Lamb. While we want to assume that these opponents will be easily distinguishable, in reality they are not. Both are signified as creatures, both make war, both have recovered from mortal wounds, both have multiple horns, both elicit worship from the nations, both give their followers a mark. The antichrist is no easily recognizable, mustache twirling villain, but a highly skilled work of forgery. The beast is even given the power of speech, or logos. The virtual indistinguishability of the beast from the Lamb is a mirror of the virtual indistinguishability of betrayal from tradition. There is only one way to see the antichrist and not be deceived; this is to see through the eyes of the beloved, animated particularly by the Paraclete’s gift of wisdom, as well as his gift of knowledge. To hand on for the good of the giver is betrayal. But to hand on for the good of the recipient is tradition. Though the beast even has speech, the one way the beast fails to imitate the Lamb is in love. The Devil can give everything but himself. And himself is precisely what the Lamb comes to give. In order to see the Lamb, then, the seer must be given wholly unto charity.

John Sees

The Revelator at Patmos who pens the great Gospel is signified by an eagle because he soars above the others and can gaze into the light of the sun without blindness. Whereas Matthew’s Gospel begins with the genealogy of Jesus, Mark’s with the testimony of the forerunner, and Luke’s with the infancy narrative, John’s Gospel begins in the very contemplative life of God—even prior to the genesis of creation. John’s Gospel has its foundation not “In illo tempore” but “In principio.” St. Thomas Aquinas notes that John is beloved above every apostle by our Lord for three reasons,[1] each related to his capacity for sight. First, his youth, implying an inherent beauty and disposition to admiratio. Second, his purity, which is the essential correlative of sight: “Blessed are the pure of heart, for they shall see God” (Matthew 5:8). Third, as an extension of his purity, St. John is perspicacious. This is to say he has an unrelenting and zealous intelligence to see beyond appearances into the heart of things. He writes through the inspiration of the Blessed Trinity as a father writing to a young, beloved Church, and he writes to the Church universal—transcendent of space and time in the economy of salvation. He writes to the Church in its infancy, but also to the Church in the last days, and the Church today. Through his sight, St. John, then, is not only a prophet in word but in deed, serving as a model of spiritual discernment—one who uniquely sees the work of the Christ apart from the work of the antichrist.

Judas and the Bread of Life

John first points the Church to Judas’ betrayal in a strange place: the conclusion of the Bread of Life discourse. I believe John does so because he wants us to know that the anti-tradition of Judas begins in a denial of the true Eucharistic presence. To be sure, John did not pen his Gospel by dividing it into chapters and verses. That comes later. But as Catholics, we aren’t allowed to believe in coincidence. It is significant that the author who gives a number, “666,” to the beast’s mark (Revelation 13:18) gives us the first glimpse of Judas’ betrayal at John 6:66:

“After this, many of his disciples drew back and no longer went about with him. Jesus said to the twelve, ‘Do you also wish to go away?’ Simon Peter answered him, ‘Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life; and we have believed, and have come to know, that you are the Holy One of God.’ Jesus answered them, ‘Did I not choose you, the twelve, and one of you is a devil?’ He spoke of Judas the son of Simon Iscariot, for he, one of the twelve, was to betray him.”

The crowd returns to their former way, the way of the beast. They are scandalized by the offer to share in divine life through a real, carnal intermingling of flesh and blood. As the Levitical prohibition against blood explicates, the life of a creature is conveyed in its blood. Ritualistic human sacrifice and cannibalism was, in that day, not at all unheard of.[2] In fact many, if not most pagan cultures would have practiced it regularly—all but three: Jews, Greeks, and Romans. Why is this significant? John tells us that Jesus uttered his teaching on the Eucharist at the perfect crossroads of Jewish, Greek, and Roman culture: Caper′na-um. John’s changing of the Greek word for “eat” in 6:54 from phagēte (from the infinitive “phagein”, to eat or consume generally; to devour as rust devours metal or as you are ‘eating up’ the contents of this article) to trōgōn (from the infinitive “trogein,” literally, to gnaw, to munch, to crunch as a cow chews her cud) cannot be mistaken: Jesus intends for his real flesh and blood to be actually consumed. Eat as beasts eat. It is hard to imagine not being scandalized by this mandate if we were in the same crowd. Peter does not understand (“Sure, Lord, transubstantiation, I got it!”), but he does offer a great assent of faith: “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life.” The crowd leaves, and Jesus does not call them back. They are scandalized by this teaching. Judas too is deeply scandalized by this teaching. But unlike the crowd that day, Judas makes the tactical decision to stay. He is well-liked, holds a position of authority among the twelve as their bursar, and he has his fill of bread. For the Iscariot, staying the course might be his best chance at the systemic social change he craves. How he too should have left! How tragic for him it was to stay and pretend to believe. And yes, how his decision that day so prefigures that of the faithless prelate. Apostolic betrayal is rooted in opposition to the Eucharist.

Judas at Bethany

The next time John points us to Judas is at Bethany. Lazarus has been raised from the dead; the women serve and adore. Mary, whose brother had been resurrected, anoints Jesus with costly ointment. Judas is indignant at her adoration. “Why was this ointment not sold for three hundred denarii and given to the poor?” (John 12:5). Sadly, here again we see a foreshadowing of a certain contemporary indignation, often cloaked by language of “social justice” and equally opposed to adoration. The great irony, unapparent in English, is that Jesus is receiving adoration here in Bethany, meaning literally “poor house” or “house of affliction.” Christ is being adored precisely by the poor. Judas opposes their adoration with noble pretense. We can imagine ten other apostles nodding their heads in agreement, “Good point! That’s a lot of nard!” While deliberately silent in the moment, John is more explicit with us in his text regarding Judas’s motives: “This he said, not that he cared for the poor but because he was a thief, and as he had the money box he used to take what was put into it” (John 12:6). Judas has a tell; and we today should note it. There is a way apart from mystical insight to know that he is lying. Nothing can be loved in the abstract. We know in the abstract, but we can only love the particular. (For instance, no man can love the abstract principle “wife,” but he better love his particular wife.) This epistemological principle sheds light on Judas who feigns concern for “the poor” in the abstract while opposing the particular, real poor in front of him immersed in adoration of Christ. John notes that the whole house was filled with the fragrance of the ointment. Judas is unmoved by the beauty of the transcendent worship as his gaze is fixed on a merely transitive good. Remarkable is the gentleness and affection with which Jesus responds to Judas. “Let her alone, let her keep it for the day of my burial. The poor you always have with you, but you do not always have me” (John 12:7). The same Jesus that calls Peter “Satan” when the latter dares to oppose his passion is far less direct with Judas. Jesus is waiting mercifully and lovingly until the end. John says nothing.

Judas on Holy Thursday

Finally, the third time John points us to Judas, we are in the upper room. Jesus announces that one of his disciples will betray him. The Gospel says, “The disciples looked at one another, uncertain of whom he spoke” (John 13:22). John includes this detail as something of an understatement. We can imagine the turmoil in the room at that moment—the uproar, the finger-pointing, the hurling of self-exonerative denials. “Not me!” “Couldn’t be me!” “I say it’s that shifty-eyed Bartholomew over there! We’ll skin him alive if it is!”

But hidden in the midst of this primal ecclesial chaos, only one apostle—the youngest of them all—chooses against joining into the mimetic rivalry of the other eleven. “One of his disciples, whom Jesus loved, was lying close to the breast (en tō kolpō) of Jesus.” Why is the Greek here significant? Because with it we can see John intends for us to make a connection back to the prologue: “No one has ever seen God; the only Son, who is in the bosom (eis ton kolpon) of the Father, he has made him known” (John 1:18). In the upper room, John develops a grand syllogism that spans and synthesizes his entire Gospel. He places himself in the bosom of the Son. The Son, we know from the prologue, is in the bosom of the Father. Therefore, the reader is left to deduce: he, John, is in the bosom of the Father, and so can see him and make him known. This loving sight of the good (who is the Father!) received and in turn made known to the beloved is authentic tradition. Apart from adoration in the bosom of the Son, we have no access to the Father. And as John’s deed of adoration conveys, we too are called to enter mimetically into this mystery of being in the bosom of the Father through the Son.

Importantly for today, John’s actions in this dire moment seem, by all appearances, to be utterly impractical. His response to the impending betrayal and destruction of his Lord doesn’t seem to be doing anything to help the situation. He simply decides to be silent and adore. This lack of action can be perplexing, especially to Peter. Seeing the youth in adoration, Peter breaks from the shouting match and beckons to John, “Tell us who it is of whom he speaks” (John 13:24). Remember, none of the others can hear his question. I suspect John does not want to answer Peter, preferring to remain in adoration. But just as he will wait for Peter after running faster and arriving first at the empty tomb, John defers here to Peter’s authority, asking his master who it is. John asks in secret, and Jesus responds in secret with words and a sign of bread—again calling us back to the source of both tradition and betrayal: the Eucharist.

John now knows it is Judas. Nobody else at table knows. It is a secret communicated between friends, an act of mutually indwelling love in which Jesus communicates the secrets of his heart to his beloved. I do not know if John’s silence was in part caused by some solemn introspection, “Could it be me?” But for us, this question must be at the forefront. I am capable of being Judas, John, or any of the other ten. More often than not, I am not John. But I must always ask, “Could it be me?” This question should compel us to silence in adoration of Christ. Through such silent adoration, John is able to know the Lord, and see the Lord’s traitor. And what does John do with this knowledge? There is a desire in us that wishes for a catharsis in the unfolding drama. If only John had jumped up, pointed, and screamed, “Peter! It’s Judas! Get him!” But John doesn’t. Why? Luke’s Gospel reminds us that these men were well armed (Luke 22:38). If John were to have told Peter the identity of the traitor, it would have been a blood bath suitable for Quentin Tarantino’s next screenplay. John knows that it is not Judas’ blood to be shed at this moment but that of the Lamb. It is the saving hour of the Lamb, and Judas is cast out. To respond with outrage is simply to cast oneself out in turn. And though the other apostles would later return, they too are also compelled out. They flee with Peter who denies Christ. They are scandalized by this saving cross. Only John is able to continue in adoration with the women at the foot of the cross, following the Lamb wherever he goes (See Revelation 14:4). Through this adoration, John is able to be present at the cross and provide consolation to the one who so thirsts for our love. And through this adoration, John rests in the bosom of Christ—thereby resting in the eternal bosom of the Father, and so can make him known. Tradition without adoration is betrayal, even though the two are identical in external appearance.

Adore and Discern

Only through adoration is St. John strengthened in love to follow our Lord into his saving hour even as Peter and the ten fled. There are many ways we can be scandalized by the treachery of Judas. Each should be carefully avoided. Sadly, the denial of the eucharist, the thwarting of adoration, the counterfeit concern for the poor, and the handing over of the transcendent in favor of merely transitive goods continue to echo today. The crowd’s denial of the true presence is as real today as it was during Jesus’ Bread of Life discourse in John 6. Judas’ opposition to beautiful worship first seen in Bethany in John 12 is stronger than ever. It’s easy to be outraged by these offenses. Anger is warranted—we can only imagine St. John’s anger as he witnessed our Lord’s torture—but the passion of anger must never be handed over to outrage lest we be scandalized. There is a sense in which we should avoid being scandalized in the event that we find ourselves, like St. John, in the midst of “ugly” worship, difficult as that is. Calvary was, after all, the “ugliest.” To be scandalized by betrayal is to be scandalized by the cross of Jesus. In the midst of such betrayal today, we the faithful have an opportunity to adore with John and the women, even amid a hostile, disbelieving crowd. We can be sure that such adoration brings consolation to our Lord who so thirsts for our love in his saving hour.

Holy Thursday calls us to meditate on the possibility that the mystical body may go the way of its head. When it does, will I respond as Judas, taking my transitive piece and fleeing the way of the beast into my own place? Or will I respond as Peter, resisting in outrage, drawing my sword in protest, until I too flee for fear? Or will I respond as John, whose adoration in the face of scandal renders him impervious to stumbling and even ordinary martyrdom? John does not flee. And when the Lord reveals to him the secret of his own betrayal, John keeps that secret. Should we see the antichrist at work today, even if we see it clearly, we may need to choose between accusation in imitation of the accuser or adoration in imitation of the adorer. And should we choose to adore, we can be confident that our silence is not an act of cowardice, but one rooted in the deepest courage. In keeping this secret of our Lord, we find the beginnings of life in his sacred passion. The Son of Man must be handed over. And the Son of Man must be handed on. The extent of our cooperation in either of these acts of tradere will depend solely on our willingness to adore. Adoration, even in the face of scandal, is the sole conduit of authentic tradition and remains the only antidote to apostolic betrayal. A younger St. John, in his enviable zeal, would prefer to call down fire from heaven and destroy the enemy (Luke 9:54). But ultimately John learned to call down another sort of fire. And he was known in old age to do so often: “Little children, let us love…” (1 John 3:18). Like John, we must learn to respond to betrayal in our midst with adoration. This Holy Thursday, during and following the Mass of the Lord’s Supper, let us recall that only one thing necessary: Adoremus.

[1] Commentary On John, 2639; Lectio 5, Ch. 21.

[2]The existence of ritualistic sacrifice and cannibalism among Barbarian and Celtic cultures in the ancient world is well recorded by modern archeological and ancient accounts alike. Classical witnesses to the fact include Julius Caesar, Pliny the Elder, and Herodotus who documented ritualistic cannibalism in Scythia as early as the 5th century BC (Histories, Book 4): “The manners of the Anthropophagi are more savage than those of any other race. They neither observe justice, nor are governed, by any laws. They are nomads, and their dress is Scythian; but the language which they speak is peculiar to themselves. Unlike any other nation in these parts, they are cannibals.” Pliny the Elder, a contemporary of Jesus, recorded similarly (Naturalis Historia Book 7, Chapter 2): “The Anthropophagi, whom we have previously mentioned as dwelling ten days’ journey beyond the Borysthenes, according to the account of Isigonus of Nicæa, were in the habit of drinking out of human skulls, and placing the scalps, with the hair attached, upon their breasts, like so many napkins.”