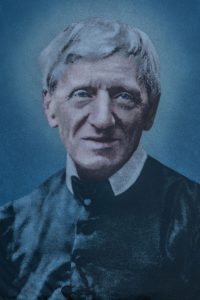

On Sunday October 13, in a solemn ceremony on St. Peter’s Square and in the presence of many faithful especially from the Anglophone world, Pope Francis canonized the English Oratorian and Cardinal, John Henry Newman (1801-1890). The new saint is remembered and venerated as a dedicated pastor of souls and the founder of the Oratory of Saint Philip Neri in England. Newman is widely considered one of the most religious thinkers in the modern age.

Among his seminal contributions stand out his essay on the development of Christian doctrine, his appreciation for the role of the laity in the Church, his profound theology of conscience, his work on education, and his theory of religious belief and certitude. This remarkable intellectual apostolate continues even today, as his writings have guided many people to embrace the fullness of Christianity in the Catholic Church.

Liturgical Seeds

The sacred liturgy does not feature prominently in Newman’s vast literary corpus. At the beginning of the 19th century, marked by post-Enlightenment rationalism, liturgical life in the Church of England was at a low point. Newman’s early religious upbringing as an Anglican consisted chiefly in reading the Bible, both in church and in the home. After completing his studies and being elected to a fellowship at Oriel College, Oxford, he took Anglican orders as a deacon in June 1824 and as a priest in May 1825. As curate of the small parish church St. Clement’s and, from February 1828, as vicar of the university church St. Mary the Virgin, Newman made preaching the focus of his pastoral work. At the same time, he was very conscious of exercising this ministry as part of the Church’s public worship. John Keble’s The Christian Year (1827) greatly influenced Newman’s understanding of the liturgical seasons and this heightened sensibility for the annual cycle of celebrating the mysteries of the faith shaped his preaching. Notably, Newman arranged the second volume of his Pastoral and Plain Sermons, published in 1835, not according to their order of delivery, which stretched over several years, but according to the liturgical year.[1]

Newman was among the founders of the Oxford Movement, which stood against the increasing tide of religious liberalism in the Church of England and intended to reclaim its Catholic heritage by building on the early Fathers of the Church and the Anglican divines of the 17th century. In his scholarly writings on early Christianity, Newman discusses liturgical themes only in passing, but his preaching contains important reflections on the nature of divine worship. Of particular note is a series of sermons preached between 1829 and 1831, which offer a rich liturgical and sacramental theology. In a sermon entitled “On Preaching,” delivered first in 1831 and again in 1835, Newman affirms that “the most blessed and joyful ordinance of the Gospel is prayer and praise…, it is the peculiar office of public prayer to bring down Christ among us—it is as being many collected into one, that Christ recognizes us as His.” Preaching is a means to an end, Newman says, which is “our praying better and living better.” The public, sacramental prayer of the Church offers us access to God’s grace, which makes us capable of living a Christian life and so offer the “acceptable sacrifice.”[2]

In the 1830s, Newman developed the idea that the Church of England, one of the branches of the undivided primitive Church, had preserved the doctrines of the patristic Church best and thus represented the “Via Media” or middle way between the errors of Protestantism and the corruptions of the Roman Church (at least on the popular level). At the same time, Newman strongly felt that the poverty of Anglican liturgical life had to be remedied. Thus he wrote in retrospect: “While I had confidence in the Via Media, and thought that nothing could overset it, I did not mind laying down large principles, which I saw would go further than was commonly perceived. I considered that to make the Via Media concrete and substantive, it must be much more than it was in outline; that the Anglican Church must have a ceremonial, a ritual, and a fulness of doctrine and devotion, which it had not at present, if it were to compete with the Roman Church with any prospect of success. Such additions would not remove it from its proper basis, but would merely strengthen and beautify it….”[3]

Prayer by the Book

The early Tractarians (the members of the Oxford Movement were known for the publication of their Tracts for the Times) advocated a full application of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, especially the daily services of Matins and Evensong, which had fallen out of use, and a more frequent celebration of Communion. Through his friend Richard Hurrell Froude (1803-1836), Newman learned about the private lectures on liturgy by Charles Lloyd, Regius Professor of Divinity (1784-1829). Lloyd highlighted the pre-Reformation elements in the Book of Common Prayer, and also introduced his hearers to medieval liturgical books. On June 30, 1834, Newman began with the daily service of Matins in St. Mary the Virgin, and from 1836 he ensured that Evensong was celebrated every day in his newly built church in Littlemore. After some consideration, Newman instituted an early Sunday morning Communion service in the University church at Easter 1837.[4]

The early Tractarians (the members of the Oxford Movement were known for the publication of their Tracts for the Times) advocated a full application of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, especially the daily services of Matins and Evensong, which had fallen out of use, and a more frequent celebration of Communion. Through his friend Richard Hurrell Froude (1803-1836), Newman learned about the private lectures on liturgy by Charles Lloyd, Regius Professor of Divinity (1784-1829). Lloyd highlighted the pre-Reformation elements in the Book of Common Prayer, and also introduced his hearers to medieval liturgical books. On June 30, 1834, Newman began with the daily service of Matins in St. Mary the Virgin, and from 1836 he ensured that Evensong was celebrated every day in his newly built church in Littlemore. After some consideration, Newman instituted an early Sunday morning Communion service in the University church at Easter 1837.[4]

Newman was careful to follow the rubrics of the Book of Common Prayer to the letter, since any alteration of the established customs would have added fuel to the controversy about the Oxford Movement, which was seen as “Romanizing.” For the Communion service, it is reported that Newman, wearing surplice and hood, always stood at the “north end,” that is, on the left side of the wooden table, unlike other Tractarians who strongly made a case for facing east in liturgical prayer to evoke the sacrificial character of the Eucharist.[5] In the new church of St. Mary and St. Nicholas he had built in Littlemore (then a village near Oxford) in 1836, Newman included a stone altar with a reredos that featured a stone cross. John Rouse Bloxam, Newman’s curate in Littlemore, had considerable freedom in his ministry, and he gradually added elements, such as two candlesticks and a credence table. Other leaders of the Oxford Movement went much further in their criticism of the state of Anglican worship and encouraged the use of Roman liturgical books. Such criticism was especially pronounced in Froude’s Remains, which caused a stir when they were published posthumously in 1838. Even Newman’s more modest measures were enough to raise suspicions in the Established Church, and he defended himself against the charge of introducing “Romanism” into Anglican worship in a long letter to the Bishop of Oxford in 1841: “I have left many things, which I did not like, and which most other persons would have altered.”[6] At the time, Newman was convinced that the desired recovery of Catholic doctrine and practice could be achieved within the framework of the Cranmerian Book of Common Prayer.

Official Sequel

But this book was to give way to another important volume of prayers. Donald A. Withey’s important work demonstrates what a profound impact the discovery of the breviary had on Newman’s spiritual journey.[7] In 1836, Newman inherited Froude’s copy of the Roman Breviary after his friend’s untimely death. He began to explore in depth the divine office, with the help of Bartolomeo Gavanti’s Thesaurus Sacrorum Rituum (1628) and Francesco Zaccaria’s Bibliotheca Ritualis (1776-1781). The result of this research was Tract 75: On the Roman Breviary as embodying the substance of the Devotional Services of the Church Catholic, dated June 24, 1836. The book-length publication consists of a historical overview of the breviary and a translation of selected offices. The praise Newman offers in his preface for “so much of excellence and beauty in the services of the Breviary” is still embedded in anti-Roman polemics, as he intends “to wrest a weapon out of our adversaries’ hands.” Stripped of its Roman additions, in particular the veneration of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the saints, the breviary, Newman claimed, is a witness to the prayer of primitive Christianity and “whatever is good and true in it” belongs to “the Church Catholic in opposition to the Roman Church.”[8] Newman also wanted to show that the daily services of the Prayer Book derive from the Roman Breviary and can be better understood in the light of the latter. At the same time, Newman was deeply impressed by the breviary’s daily round of prayer, with the psalms at its heart, and suggested Anglicans could use it for private devotions.

Newman’s Tract 75 was widely received and inspired his friends Robert Williams (1811-1890) and Samuel Wood (1809-1843) to embark on an English translation of the entire Breviarium Romanum. The project was eventually abandoned, mainly because of Newman’s concern about the hostility such a translation (even in an edited form) would meet at a time when antagonism towards the Tractarians was growing in the Anglican Establishment.[9] As part of Tract 75 and of his involvement in the breviary project, Newman produced English versions of Latin office hymns, which anticipated the better-known translations of the Anglican John Mason Neale (1818-1866) and of his fellow Oratorian Edward Caswall (1814-1878). Not all of Newman’s 47 translations were printed during his lifetime, and Withey’s study includes ten hymns, which had not appeared in print before, from notebooks kept in the archive of the Birmingham Oratory.[10]

Newman’s love for the Divine Office illumined his path towards the Catholic Church. When in spring 1842, beset by doubts in the theory of the Via Media, he retired to Littlemore for a period of prayer and study, joined by a number of like-minded friends, the daily recitation of the Roman Breviary (with some omissions, such as the Marian antiphons) became a staple of their community life. After Newman and two of his companions were received into the Catholic Church on October 9, 1845 by Blessed Dominic Barberi (1792-1849), a small but significant change occurred in the community’s daily prayer. While they had recited the Latin text in the Anglicizing manner familiar from school and university, after that momentous day they adopted the Italianate pronunciation known as “Church Latin.”[11]

Rest in Peace

In his Apologia, Newman gave a moving testimony about the spiritual peace he found after having been received into what he described to his family and friends as “the one true fold of the Redeemer.” Newman writes, “From the time that I became a Catholic, of course I have no further history of my religious opinions to narrate. In saying this, I do not mean to say that my mind has been idle, or that I have given up thinking on theological subjects; but that I have had no variations to record, and have had no anxiety of heart whatever.”[12] What this passage does not convey is the fact that Newman came into contact with the fullness of Catholic liturgy only after his conversion. Ian Ker observes that Newman’s embrace of Catholicism was to a large extent intellectual and preceded his actual experience of it: “while Newman knew a very great deal about the early Church, he knew extraordinarily little about contemporary Catholicism, apart from its formal doctrines and teaching.”[13]

As an Anglican, Newman found contemporary Catholic liturgical and devotional life emotionally attractive, but tended to avoid it because of his intellectual conviction that Rome had introduced many novelties and corruptions to the pure faith of the primitive Church.[14] Both in his preaching and in letters to friends, Newman repeatedly emphasized that conversion is a slow work and that such a decision needs time and reflection to mature. Had he followed his heart alone, he may have joined the Catholic Church years earlier, as many of his friends from the Oxford Movement did. Characteristically, however, Newman wanted heart and mind to agree. Once the truth of the Catholic faith became a certainty to him, he threw himself fully into the Church’s liturgical life. Newman’s first novel Loss and Gain: The Story of a Convert, published anonymously in 1848, contains warm and fervent descriptions of Mass and Benediction by the Catholic converts Willis and Reding, with clear autobiographical echoes.[15] In the appendix to his Apologia Pro Vita Sua, Newman wrote: “I looked at her [the Catholic Church]; – at her rites, her ceremonial, and her precepts; and I said, ‘This is a religion’; and then, when I looked back upon the poor Anglican Church, for which I had laboured so hard, and upon all that appertained to it, and thought of our various attempts to dress it up doctrinally and aesthetically, it seemed to me to be the veriest of nonentities.”[16]

Newman had a particular devotion to the Blessed Sacrament and found in the presence of Christ in the tabernacle great strength and comfort. After his ordination to the priesthood on May 30, 1847, the daily celebration of Holy Mass became the heart of his spiritual life. Newman’s chosen vocation as an Oratorian had a particular liturgical dimension. Since its foundation in 1575, the Congregation of the Oratory had been known for its attention to solemn liturgy and sacred music. The Oratorian houses in Birmingham and London resumed this tradition from the moment of their foundation, despite their limited initial resources and the occasional criticism they received for undue attention to such matters.[17]

Liturgical Heart

In conclusion, there is no doubt that the sacred liturgy was at the heart of St. John Henry Newman’s life and thought, even though it obtains a minor role in his enormous written opus. As is often the case with Newman, it is his intellectual and spiritual development as an Anglican that attracts greater notice.

Once he became Catholic, he truly found peace and serenity, even in the midst of severe external trials, and his prayerful dedication to the Church’s divine worship made his priestly life exemplary.

[1] See Joseph Alencherry, “Newman, the Liturgist: An Introduction to the Liturgical Theology of John Henry Newman”, in Newman Studies Journal 13 (2016), 6-21, at 12.

[2] John Henry Newman, Sermons, 1824-1843. Vol. 1: Sermons on the Liturgy and Sacraments and on Christ the Mediator, ed. Placid Murray (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991), 25-26. On these sermons, see Alencherry, “Newman, the Liturgist,” and Robert C. Christie, “Conversion through Liturgy: Newman’s Liturgy Sermon Series of 1830,” in Newman Studies Journal, 3 (2006), 49-59.

[3] John Henry Newman, Apologia Pro Vita Sua, Being a History of His Religious Opinions, New Impression (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1908), 166.

[4] See Donald A. Withey, John Henry Newman: The Liturgy and the Breviary. Their Influence on his Life as an Anglican (London: Sheed & Ward, 1992), 8-17.

[5] See the monograph of Alf Härdelin, The Tractarian Understanding of the Eucharist, Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis 8 (Uppsala: Almqvist and Wiksell, 1965).

[6] As quoted in John Henry Newman, The Via Media of the Anglican Church, New Impression, 2 vol. (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1908), vol. II, 419.

[7] See Withey, John Henry Newman: The Liturgy and the Breviary, 82-89.

[8] John Henry Newman, On the Roman Breviary as Embodying the Substance of the Devotional Services of the Church Catholic, Tracts for the Times 75 (London – Oxford: J. H. Parker – J. G. and F. Rivington, 1836), 1-2.

[9] See ibid., 25-66.

[10] bid., 115-123; see also Withey’s annotated list of the hymns translated by Newman on 124-136.

[11] See ibid., 73-81.

[12] Newman, Apologia Pro Vita Sua, 331.

[13] Ian Ker, “Newman’s Post-conversion Discovery of Catholicism,” in Newman and Conversion, ed. Ian Ker (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1997), 37-58, at 37.

[14] This tension is evident from the first stanza of the poem “The Good Samaritan,” written in Palermo on 13 June 1833, while he was recovering from a serious illness:

Oh that thy creed were sound!

For thou dost soothe the heart, thou Church of Rome,

By thy unwearied watch and varied round

Of service, in thy Saviour’s holy home.

I cannot walk the city’s sultry streets,

But the wide porch invites to still retreats,

Where passion’s thirst is calmed, and care’s unthankful gloom.

—John Henry Newman, Verses on Various Occasions, New Impression (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1903), 153.

[15] See Ker, “Newman’s PostConversion Discovery of Catholicism,” 51-54.

[16] Newman, Apologia Pro Vita Sua, 340.

[17] In a letter to the editor of the Catholic weekly The Tablet, dated October 20, 1850, Newman writes in response to a disapproval of the Oratorians’ regular celebration of Vespers: “… we are bound by our rule to the solemn Ritual services of the Church, and we keep it. Both our own House here, and the Oratory in London, sings High Mass and Vespers every Sunday, and other principal festivals … . The Congregations of the Oratory have ever been remarkable for their exact attention to the rubrics of the Ritual …”; The Letters and Diaries of John Henry Newman, Volume XIV: Papal Aggression, July 1850 to December 1851, ed. Charles Stephen Dessain and Vincent Ferrer Blehl, S.J. (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1963), 106.