The traditional vesting prayers accompanying each item of the celebrant’s attire link the particular vestment to some spiritual reality. The prayer recited when assuming the alb, for example, reminds the priest that it is a symbol of being washed whiter than snow (Psalm 90:9) in the blood of the Lamb (Revelation 7:14), an appropriate reminder of the precious price of baptism. The stole is accompanied by a plea for the joy of eternal life despite one’s unworthiness. When the chasuble, often the heaviest garment of them all, is put on, the celebrant is reminded of Our Lord’s words in Matthew 11:30 that his “yoke is easy” and his “burden is light.”

In a similar way, the collects to be sung at Mass are appropriately clothed in the rich melodies which the Church holds in her musical wardrobe. Certainly, there are many overt prayers in the Psalms linking music and the offering of one’s self to God. Indeed, one might say that the garment of song, when it clothes the texts of the liturgy, is a symbol, a physical manifestation of the worship of God. Many a choir has prayed the following text before rehearsal, which captures this connection between song and the sacrifice one offers with that of Christ at the Mass: “May the words of my mouth, and the meditation of my heart, be acceptable in thy sight, O Lord, my strength, and my redeemer” (Psalm 19:15).

Surely this could also be the prayer of any priest singing the orations. Let us see, then, how, on both a theoretical and practical level, the singing of the collects by priests can achieve for pastors and parishes alike a tailor-made fit of music and words.

The Mass is no mere activity among many: it is the “sacred action surpassing all others” (Sacrosanctum Concilium (SC) 7) and it calls for external symbols to express this spiritual reality.

Clothes Make the Priest

Before examining these sung parts of the Mass, let us look how close the parallel between music and vestments is. When a priest is clothed to celebrate Mass, he lays “aside all earthly cares” (“Cherubic Hymn” in the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom), donning clothes that he wears at no other time, so that he might become detached from ordinary life. He takes time away from his charitable works, from his private prayers, from the administration of the other sacraments, from appointments. The Mass is no mere activity among many: it is the “sacred action surpassing all others” (Sacrosanctum Concilium (SC) 7) and it calls for external symbols to express this spiritual reality.

And these external symbols are appointed by the Church. The priest wears white in Paschaltide, red for the martyrs, a stole in the manner the Church has assigned to his office. He prays the prayers given to him, proclaims the Gospel set in the liturgical book, makes the gesture assigned him by the rubrics. The absence of choice and the obedience of taking up that which Christ’s bride has dictated is an act of fidelity to the mystery he is about to celebrate and to his identity as a priest of Jesus Christ.

Even in the matters left to the discretion of preaching, the priest’s formation is meant to smooth out his rough patches and bind up his wounds so that the words he speaks of his own accord allow Christ to shine forth, rather than serving as a stumbling block. He must never become so wrapped up in his own style and agenda as to think that his words are the most important and persuasive element of the liturgy, and that he therefore has total freedom to do whatever he wishes. Here, the words of St. Paul guide the priest’s choice: “Although I am free in regard to all, I have made myself a slave to all so as to win over as many as possible” (I Corinthians 9:19).

All these visible and audible elements are a reminder to both the priest and his people that he goes to the altar of God to celebrate the Mass in persona Christi. They serve as a healthy detachment from one’s self, one’s goals, and one’s ego. At the Mass, the priest is not a private person but is rather a minister of the Church of Jesus Christ, and a humble servant of Our Lord. The prayer of St. John the Baptist can surely be that of the priest: “He must increase; I must decrease” (John 3:30).

The Church’s Seamless Tones

It should be noted, however, that the analogy between music and vestments is not original to this author. The usual and lovely translation of Pius X’s 1903 motu proprio Tra le Sollecitudini states that the principal munus (“service”) of music is to “clothe with suitable melody the liturgical text proposed for the understanding of the faithful” (emphasis mine). Music is a sort of vestment for the Church’s words and those of scripture, propelling them into the realm of the sacred, where they can serve as a sort of sacramental microphone, amplifying the voice of God, making it more “living and effective” (Hebrews 4:12) in the hearts of hearers.

The music “specially suited to the Roman liturgy” (SC, 116) is Gregorian chant, and within this body of repertoire, the musical genres give external witness to the spiritual and liturgical appointment of the text. The melody of an introit, with its distinctive stylings and flowing style, move the procession and hearts of those present up to the altar of God. The tunes of the Graduals, Alleluias, and Tracts, with their superfluous melismas (numerous notes on a single syllable) afford the opportunity to meditate on the Word of God during the time appointed for the readings (see General Instruction for the Roman Missal, 56, 61). The lack of finality in the priest’s parts of the dialogues and the simplicity of the melodic content beckon the faithful to engage in a sacred dialogue; we sing to one another because this is no ordinary conversation, gathered as we are in the sight of the Lord. In all these genres, when sung in Gregorian chant, we hear the words appointed by the Church, no mere preference of the music director or priest.

The lack of finality in the priest’s parts of the dialogues and the simplicity of the melodic content beckon the faithful to engage in a sacred dialogue.

All this is true also for the tones the Church has given for the orations of the celebrant. He does not make a selection of the words he takes upon his breath and lips. They are proposed by the Church, who serves as a mother, teaching her children to pray through all the highways and byways of the liturgical year and in the very shape of the Mass. And when these prayers are clothed with the tones appointed for them by the Church in her chant tradition, the priest relinquishes even his own tone of voice, assuming instead the Church’s tone of voice. United to Christ’s bride, the Church, through sharing the Church’s solicitude for even the least detail of the liturgy, he is conformed ever more perfectly to the bridegroom. The act of singing in this way, though not the most profound one a priest will do in his life, is nevertheless a small, habitual way in which he can make St. Paul’s assertion his own: “yet I live, no longer I, but Christ lives in me” (Galatians 2:20).

For the people, too, the singing of the priest, rather than his mere speaking, is a reminder that the sacred liturgy is the “summit toward which the activity of the Church is directed” (SC, 10). No one typically goes around singing one’s greetings to friends and colleagues, or chanting a summary of one’s thoughts in a business meeting or classroom. We do so, however, in the liturgy because it is a privileged locus for an encounter with God, the place where all that we hear and see and taste and smell and touch should point like arrows, directing our hearts and minds to the presence of Christ, the paschal Lamb. The sacred liturgy is the work of God which Christ’s flock participates in and offers their own sacrifice of praise in singing an “Amen” in response.

Try Music On—in Theory and Practice

In some ways, the Church has been overly reliant on words to hand on the faith in recent decades. There is the mistake of thinking that if only the faith were explained more clearly, more convincingly, that it might be accepted and take deeper root. This may be true. And it is right and just that we have a faithful translation of the Roman Missal to sing. Nevertheless, humans learn in many ways, not just through words. We are catechized by beautiful things, acts of charity, gestures of worship, buildings which bespeak the presence of God.

Singing, too, is one such witness to the truth of our faith, since cantare amantis est (“singing is for the one who loves”). Singing is a means of preaching the Gospel that amplifies the words of the liturgy and sacred scripture, and really doesn’t take much more time than speaking, though it does demand greater physical exertion. While the Church in her wisdom does allow the liturgy to be spoken, she also knows the value of solemnity in allowing the sacred mysteries to take deeper root in the hearts of her children.

While the Church in her wisdom does allow the liturgy to be spoken, she also knows the value of solemnity in allowing the sacred mysteries to take deeper root in the hearts of her children.

When the Mass is always spoken, it can lull us into a sleep, closing our eyes to the nature of what we have seen and touched (cf. I John 1:1). The sacrality of singing the liturgy wakes us up, preaching to us the reality of God’s work among men, of the presence of Christ in the Word of God, and especially of the nature of the Most Holy Eucharist. Catholics believe that this is no mere symbol, no simple meal, no regular gathering of friends, but is rather the place in which Christ comes to us in his very body, blood, soul, and divinity—because this is no ordinary event, we sing, and in this set-apart way of acting we preach and learn more deeply the true presence of God.

Because music is such a perfect fit for the Mass, it ought not only be a matter of theoretical know-how for priests but also a matter of practical—and practicable—efficiency. However, not every priest has had the opportunity to grow in competence and confidence at singing his parts of the Mass. Many have not learned how to sing the presidential prayers correctly. Perhaps their experience has mostly been with the “tonus inventus,” the made-up tone that never quite gets the formula right, leaving the impression about how to do it a muddled mess in one’s mind. Or maybe he hasn’t even had the opportunity to learn to match pitch or fix vocal faults which make his singing less pleasant than befits the liturgy.

Singing is normative for the human person, and can be learned. It’s not simply an innate talent that either one has or not, with nothing to be done about it.

Except in rare cases of physiological defect, singing is normative for the human person, and can be learned. It’s not simply an innate talent that either one has or not, with nothing to be done about it. If one struggles with matching pitch, here are some steps that might be taken with a trusted musician guide to learn to sing.

- Have a trusted musician sing a series of two pitches, on a neutral syllable like “nu,” with the second note going up, down, or staying the same. If it is difficult for the listening priest to identify the direction of the second note, the musician can make the interval between pitches wider, or make each note a little longer. This develops the priest’s ability to hear difference in pitch, in the same way that he can likely already tell the difference in tone of voice (angry, happy, etc.), but still without the necessity of vocal production himself.

- A musician plays a pitch on the piano and then either sings the same note or a different note with the priest identifying whether the note sung is the same or different. (Again, this exercise is about developing the ability to compare two sounds but without the priest singing himself.)

- A priest sings any one pitch and, while sustaining the sound, makes the pitch go up or down. This step moves into the priest experiencing control in his own voice over the pitch, yet without the need to match it to an external source.

- The musician plays a note on the organ or piano, sings the same note, and then the priest attempts to sing that same pitch. A good pitch might be something like B2 (a little more than an octave below middle C) on a piano, which is in the speaking/chest register of most men. The priest should judge whether he got the correct pitch or not. Here, even the ability to identify that one didn’t sing the correct note is an important step in vocal control and the use of the ear. With patience, one will learn to identify whether it was correct or not, and, if not correct, to adjust it to the correct pitch.

- Once able to match a single pitch in the speaking register, a priest should try singing an oration on a single note in that register. This is a further step in vocal control.

- Extend the range of single pitches that the priest can match by going up through the middle register to at least an F3 or F#3 (just below middle C), still well before needing to go into falsetto. Again, try singing the oration on a single note, now in this higher register. Once the priest can match in a more expanded range, the upper range of notes can be approached from the bringing the falsetto down, or by extending the middle register upwards—whatever works.

- Try an exercise that prepares for the singing of the orations. For example, if one is preparing what is labeled as the “solemn tone” in the current Roman Missal, sing the final “Amen,” with the ascending whole step on “-men.” Start in a comfortable range and raise or lower the exercise by half steps.

A Few Grace Notes…

A next step in singing the orations well is working on the breath and controlling the speed of enunciation of the text. Singing requires more breath than speaking, and breathing for singing usually involves inhalation through the mouth, rather than the nose, and should also involve an expansion of the belly in a deep breath. As a corollary, the singing sound is louder than speaking. As an exercise, one might try a controlled exhalation for four seconds, waiting for two seconds, and then inhaling for four seconds, taking in noticeably more breath than when speaking. Once deep breathing is established, a recitation of the text of a phrase of a collect on a single pitch can be substituted for the exhalation. Finally, once that becomes comfortable, one should sing the oration in a manner which emphasizes the consonants in the sound, enunciating more clearly than in normal conversation. This will slow down the speed of the text delivery, but not too much. Generally, aim for something nearly the same speed as speech when singing on one pitch. When the pitch moves, it sounds lovely and aids in comprehension to slow slightly.

All these elements, when combined, aid the intelligibility of the presidential prayers for the faithful, and reduce the need for loud microphone volumes—a service in charity!

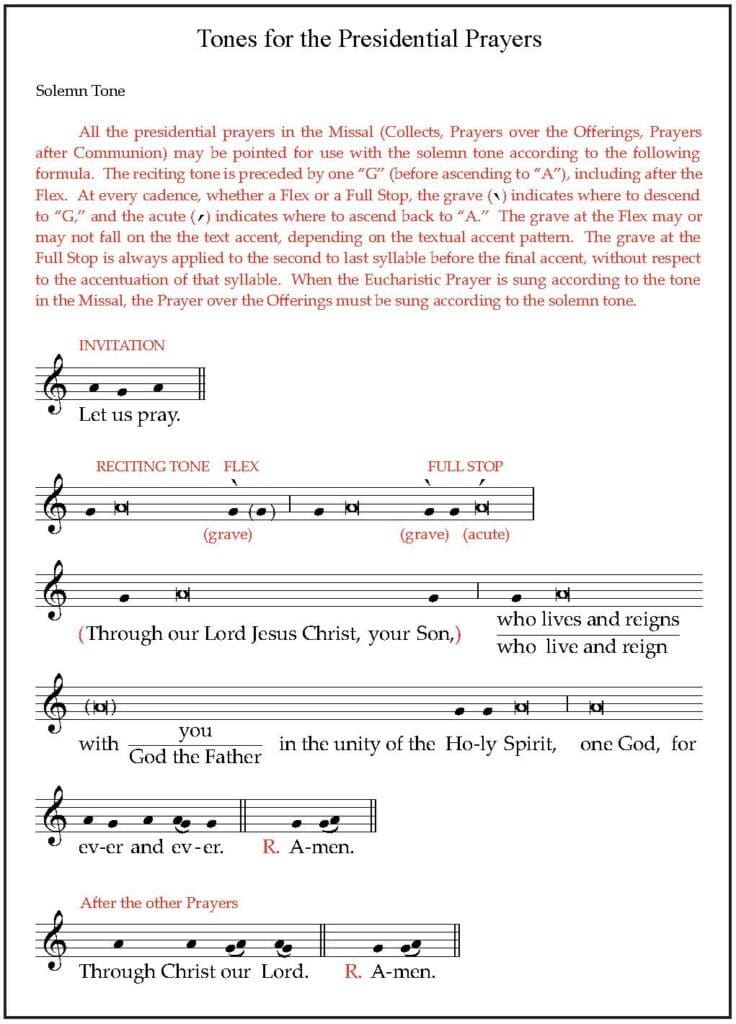

The final step in singing a presidential prayer is using the actual tone, one of the stars in the beautiful galaxy of Gregorian chant melodies. I recommend starting with the “solemn tone” in the appendix of the Roman Missal. While the pitch content of the “simple tone,” with its descending minor third, may be more “in the ear” of the priest, the large drop just before the doxology proves problematic for the beginner, especially if one aims at getting it right.

Begin with singing (or even thinking) the “Amen” (as above, SOL SOL LA) to get the correct pitches in one’s mind. Then try “Let us pray” on LA SOL LA. Next, practice the doxological formulae given in the missal appendix. Then, work to ensure the correct division of the collect into its logical parts, usually two phrases/clauses followed by a doxology. Often, the first phrase of the prayer addresses God in some way, calling to mind something he has done. Many times, the second phrase begins with the word “that,” before finishing with a strong verb of request that flows logically from the first phrase.

In the “solemn tone,” the first phrase begins with the first syllable of the prayer on the lower pitch (SOL) and beginning with the second syllable a recitation of most of the phrase on the upper pitch (LA). The first phrase descends to the lower pitch on the last syllable of the phrase, before going on to the second phrase. The second phrase, again beginning with the lower pitch and recitation of the majority of the phrase on the upper pitch, ends with two syllables (regardless of word accentuation) back down on the lower pitch before the final accented syllable in the phrase moves the conclusion of the phrase back up to LA.

When working to get this correct, it is often a matter of judging where to go down to SOL for two syllables before the final accent of the phrase that is most difficult. The most helpful preparation one might do, if short on time, is to make a mental note of where the second phrase begins, and what the last accented syllable in the second phrase is, then backing up two syllables to note where one must move the pitch down before ascending to the conclusion.

One should aim for correctly singing the tone! Certainly, even singing on a single pitch elevates the sense of the sacred in the delivery of the text, especially when combined with a purposeful enunciation, but the structure of the tone is itself an important aid in supporting the meaning of the prayer one sings. After all, this is the proper garment the Church offers the priest as clothing for the presidential prayers. Moreover, spending just a moment of time in preparing these short prayers is food for meditation for the priest. It can also help him see more clearly the meaning of the texts the Church appoints for him to pray, and this process can give a sense of the purposeful movement of time throughout the liturgical year.

Let us bring to God the finest attire we can muster, celebrant and congregation singing together.

I will rejoice heartily in the LORD,

my being exults in my God;

For he has clothed me with garments of salvation,

and wrapped me in a robe of justice,

Like a bridegroom adorned with a diadem,

as a bride adorns herself with her jewels (Isaiah 61:10).

Dr. Jennifer Donelson-Nowicka holds the William P. Mahrt Chair in Sacred Music at St. Patrick’s Seminary in Menlo Park, CA.