And let them know that when we worship the Lord in flesh, it is not a creature that we worship, but the Creator as clothed with a created body.1

–Saint Athanasius

A central consideration in the fourth-century controversy over Jesus’ divinity was the worship of Jesus: are we worshiping a creature? Or, even if Jesus is God in the flesh, are we worshiping created flesh? All parties involved in the Nicene controversies “confessed Jesus Christ in the context of worship. The question,” writes theologian Khaled Anatolios, “was precisely how to interpret such worship.”2 The Church came to define the doctrine of the divinity of Christ in accord with the actual practice of the worship of Jesus in the liturgy. “At one point in his work against the Gnostics,” writes Robert Louis Wilken, “Irenaeus observed that they say the ‘bread over which thanks have been given is the body of the Lord and the cup is his blood,’ yet they do not worship Christ as the Son of God. Either they should alter their view of Christ or give up the practice of celebrating the Eucharist. To which he adds, ‘Our teaching is consonant with what we do in the Eucharist, and the celebration of the Eucharist establishes what we teach.’”3

In a similar way, the development of the Church’s practice in the worship of the Eucharist had a profound effect on the development of doctrine through the centuries: how can we worship what appears to be bread, as God?

Early Eucharistic Evidence

The worship of Jesus is of course the logical corollary to the worship of the Eucharist, the flesh and blood of Jesus—and vice-versa. St. Athanasius’ words encapsulate the teaching of the Nicene period as regards the worship of Jesus: “We by no means adore a creature; this is an error of the heathen and the Arians. But we do adore the Lord of the creature, the God-Logos made flesh. For although the flesh is of itself something created, it has become the body of God. But in adoring this body we do not separate it from the Logos, nor do we detach the Logos, when we wish to adore Him, from His flesh.… Who, then, is so foolish as to say to the Lord: ‘Depart from Thy body, that I may adore Thee’?”4

Ludwig Ott, in his storied Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma, aptly summarizes the dogmatic formulation: “In opposition to the double veneration proposed by the Nestorians [adoring the Son of God on the one hand and the Son of Mary on the other], and the single veneration of the Monophysites, directed to the Divine nature alone, or to an alleged mixed nature, the Fifth General Council of Constantinople (553) declared that the Incarnate Word with His own flesh (μετὰ τῆς ἰδίας αὐτοῦ σαρκός) is the object of the one adoration.”5

St. Thomas Aquinas refines this teaching (STh., III q.25 a.2): in the union of his divine and human natures, his created human flesh is not worshiped for its own sake, but because of its union with the person of the Word. Theologian Joseph Pohle sums up Aquinas’s argument in this pithy statement: “Whatever belongs to a person substantially (as in this case the humanity of Christ), is worthy of the same specific veneration as the person himself.”6

Who, then, is so foolish as to say to the Lord: ‘Depart from Thy body, that I may adore Thee’?

–Saint Athanasius

The assertion that the Word made flesh deserves adoration is seen early on in St. Irenaeus (see above). In the early centuries Christ’s personal presence in the Eucharist is clearly recognized and emphasized in the context of receiving the Eucharistic elements themselves. Here is the third century Jerusalem Catechesis: “Therefore, when you come to receive, do not approach with hands extended and fingers open wide. Rather make of your left hand a throne for your right as it is about to receive the King, and receive the Body of Christ in the fold of your hand, responding, ‘Amen.’…Take care that you lose not even one piece of that which is more precious than gold or precious stones.”7

Even earlier, the Alexandrian theologian Origen (b. 185; fl. c. 200–254) makes reference to showing cautious care for each particle: “You who are accustomed to take part in the divine Mysteries know how, when you have received the Body of the Lord, you exercise every caution and reverence lest a particle of it fall and any of the consecrated gift perish. For you believe yourselves guilty—and you believe rightly—if any of it falls through your negligence.”8

The early focus of the reality of Christ’s presence in the Eucharist was centered on the communion of the faithful. St. John Chrysostom (349–407), Archbishop of Constantinople, speaks of this with his congregation: “How many there are who still say, ‘I want to see his shape, his image, his clothing, his sandals.’ Behold, you do see him, you touch him, you eat him! You want to see his clothing. He gives himself to you, not just to be seen but to be touched, to be eaten, to be received within.”9

Chrysostom responds to this desire to see and touch Jesus by reminding the faithful that the sacred Body of Jesus is touched in the Eucharist and is even “received within.” Yet, even as early as Chrysostom, adoring the Lord’s presence outside the immediate context of communion is hinted at: “This body, even when lying in the manger, the Magi reverenced…and came and worshiped…. Let us then, the citizens of heaven, imitate these foreigners…. For thou dost see Him not in a manger but on an altar…Him who is the Lord…Himself.”10

How many there are who still say, ‘I want to see his shape, his image, his clothing, his sandals.’ Behold, you do see him, you touch him, you eat him!

–Saint John Chrysostom

Again, Chrysostom, while inviting the faithful to fruitful reception, invites them to worship the Lord, present on the altar. Of course, Chrysostom is not alone among the Fathers in this. St. Augustine (354–430), in a similar context, invites the faithful to worship as well: “In my uncertainty I turn to Christ…and then I discover how, without idolatry, the earth may be worshiped, how God’s footstool may be adored without impiety. He took earth from earth, because flesh comes from the earth, and he received his flesh from the flesh of Mary. He walked here below in that flesh, and even gave us that same flesh to eat for our salvation. But since no one eats it without first worshiping it, we can plainly see how the Lord’s footstool is rightly worshiped. Not only do we commit no sin in worshiping it; we should sin if we did not.”11

With these references to physical acts of adoration, Augustine makes clearer the worship due the Lord under the Eucharistic species.

Extra-Liturgical Worship

The passages above focus on the liturgical encounter and reception of the Eucharist. But there are several passages from the Fathers that begin to point toward extra-liturgical Eucharistic worship. The first is from the Jerusalem Catechesis: “While [the Precious Blood] is still warm upon your lips, moisten your fingers with It and so sanctify your eyes, your forehead, and other organs of sense.”12 Father James T. O’Connor, longtime seminary professor at Dunwoodie, NY, puts this in Patristic context, “Touching the forehead and eyes with the Host before receiving the Sacrament was apparently something common in some parts of the Eastern Church.”13 Yet, something more is happening here: the precious blood is being applied as an ointment or a “medicine of immortality.” Although this practice takes place in the context of Eucharistic communion, it is more than just reception.

In the next example, St. Gregory Nazianzus recounts how his sister Gorgonia, when very sick, went to the altar at night to encounter the Lord: “Despairing of all other help, she betook herself to the Physician of all, and, waiting till the dead of night, when the disease was somewhat abated, she prostrated herself with faith at the altar, and calling upon Him who is honored thereon, with a loud voice, and under every title, recalling all His miraculous works, for she was familiar with those of old as well as the new, she finally committed an act of pious and noble impudence. She imitated the woman whose hemorrhage was dried up by the hem of Christ’s garment. And what did she do? Placing her head, with a similar cry, on the altar, and pouring abundant tears upon it, as she who had once watered the feet of Christ, she vowed that she would not loose her hold until she obtained her recovery. Then she anointed her whole body with her own medicine, even a portion of the consecrated precious Body and Blood which she treasured in her hand, and with which she mingled her tears.”14

In this account, it is notable that St. Gregory Nazianzen parallels his sister’s time of prayer at the altar with two stories from the Scriptures of encounters where the characters actually touch the Lord Jesus himself. Historian James Monti sums up the value of this story: “The meaning of the text is not sufficiently clear for us to identify it as our earliest extant testimony of prayer to the reserved Eucharist. Nonetheless, with Gorgonia going into the church at night as if she could especially place herself at the feet of Christ there, we certainly find in this episode at the very least the concept of compositio loci in the form of private prayer before the altar that in the centuries to come was to fuse with the Church’s belief in the Real Presence, and lead to the birth and development of extraliturgical eucharistic adoration.”15

Pre-sanctified Tradition

Regardless of whether Gorgonia was seeking to encounter the Lord in the reserved Sacrament, the abiding reality of the Lord’s presence was subsequently celebrated in the liturgy of the presanctified gifts by at least the seventh century (A.D. 692 or even 617), “but it could reasonably be older.”16 The liturgy of the pre-sanctified gifts is celebrated in Byzantine churches during the Lenten season, similar to our current Good Friday service, where the Eucharistic sacrifice is not offered, but Holy Communion (consecrated at a previous liturgy) is distributed.

The seventh-century Chronicon Paschale (A.D. 630), a document dealing largely with the dating of Easter and the liturgical calendar, relates that the following antiphon was sung when the reserved Sacrament was brought to the altar from the sacristy: “In this moment the Virtuous [sic] of the heavens invisibly adore God with us. Behold that the King of Glory makes His entrance, behold that the mystic sacrifice is presented: approach with faith and with fear, in order to become participants of the life eternal. Alleluia.”17

These lines express the reality of Christ’s presence as the “King of Glory makes His entrance” in the reserved Sacrament. Moreover, this antiphon indicates that the people are adoring the Lord in the Eucharistic species. It was on the heels of this adoration of the reserved Eucharistic species, during “the iconoclast controversy in the eighth and ninth centuries,” that “the question of the eucharistic change was clarified” in the Christian East by “affirming that…Christ is really present in the Eucharist—really and permanently present, as the Liturgy of the presanctified gifts makes clear.”18 It is interesting to note here that Paschasius Radbertus’ (c. 790–c. 860) formulations asserting a strong Eucharistic realism (“the flesh born of Mary”) closely parallel those surrounding the Second Council of Nicea (787), where the Council condemned counter-assertions that the bread and the wine were merely signs.19 Less than 100 years previous to Paschasius’ treatise, St. John of Damascus wrote, “The bread and the wine are not a figure of the body and blood of Christ (God forbid) but the body of the Lord itself that is filled with Godhead, since the Lord Himself said, ‘This is My’—not figure of the body but—‘body,’ and not figure of the blood but ‘blood.’”20

All of these actions and texts illustrate the reverence and even adoration toward the Eucharistic species throughout the first seven centuries of the Church. The next five centuries saw more of the same. Yet, a certain momentum grew regarding this devotion. In particular, reservation in tabernacles and pyxides (containers for taking the Blessed Sacrament to the sick)21 would become more common: “Toward the end of the ninth century, directives stipulating reservation [of the Sacrament] at the altar began to appear.”22 This is significant because it likely marks a deepening sense of devotion “that took precedence even over the need to protect the Blessed Sacrament from sacrilege.”23 On top of this, the Eucharist was increasingly being carried to the sick with the ceremony of candles, and during the Holy Thursday reservation with candles and incense, even going so far as to “bury” the Blessed Sacrament in a tomb-like shrine.24

Well before this time, the introduction of the Agnus Dei into the Mass at the papal court by Pope Sergius (687–701) shows a personal interest in directing prayer specifically toward the Eucharistic species. The introduction of the Angus Dei becomes, as Father Josef Jungmann notes, “the first indication of a more personal intercourse with Christ present in the Eucharist.”25 Following upon this introduction is the indication in the early eighth-century Ordo Romanus Primus where the pope and his deacon “reverence the Holy Elements with bowed heads.”26 The high point of this devotional development was the 12th-century institution of the “elevation of the Host and the Precious Blood after the Consecration…so that the faithful might look at and adore the Lord present in the Sacrament.”27

Source(s) of Devotion

It has been frequently argued that “the cult of the Eucharist outside Mass was a direct outgrowth of theological debate and conflict over questions of real presence and substantial change.”28 While some of the Eucharistic devotions certainly did develop out of these controversies, the development of devotion to the Eucharist clearly arose steadily over the centuries. Theologian Nathan Mitchell argues that when the liturgy diverged from its roots as a communal meal, the Mass turned into a dramatic reenactment of Christ’s life with sacred food, and only because of this did the extra-liturgical devotion to the Blessed Sacrament develop. While this is not the place to engage Mitchell’s argument, it should be clear that devotion to the Blessed Sacrament was developing throughout the centuries, even in the context of situations associated with Eucharistic communion.

In the eleventh-century controversy with Berengar of Tours, Lanfranc of Canterbury opposed Berengar with great doctrinal dexterity. Yet what may be overlooked is that Lanfranc’s doctrinal ferocity was rooted in a deep devotional faith. A prime example is the elaborate carrying of the Blessed Sacrament for the Palm Sunday procession, where genuflections by the choir, the servers, and the people are mandated at the beginning and end of various canticles. The most striking is the description of the Blessed Sacrament passing in the midst of the faithful: “As the bearers of the shrine pass by, all are to genuflect, not all at once but one by one on this side and on that as the shrine passes before them.”29 As historian Darwell Stone notes, this elaborate devotional procession “may previously have been in use at Bec,”30 the location of Lanfranc’s previous community. This devotional practice of genuflecting before the Blessed Sacrament is the deep root that helped Lanfranc formulate his theological stance against those who opposed Eucharistic realism, first against John Scotus-Erigina and Ratramnus, and then against Berengar.

As extra-liturgical devotion to the Eucharist gradually formed in the Church over the centuries, the Church’s understanding of the Eucharistic mystery became more precise. Indeed, it is remarkable that the Eastern iconoclast controversy and the Western Eucharistic controversy both helped the Church formulate the one Eucharistic faith in similar times and distinct contexts. Though the controversies were different, the common thread for both East and West was the worship of the Lord’s Body and Blood. This is a decisive aspect of the Church’s faith with regard to the formation of the Eucharistic doctrine: lex orandi, lex credendi: “The law of prayer is the law of faith: the Church believes as she prays” (CCC, 1124).

Jeremy J. Priest is the Director of the Office of Worship for the Catholic Diocese of Lansing, MI, as well as Content Editor for Adoremus. He holds an STL from the Liturgical Institute of the University of St. Mary of the Lake, Mundelein, IL. He and his wife Genevieve have three children and live in Lansing, MI.

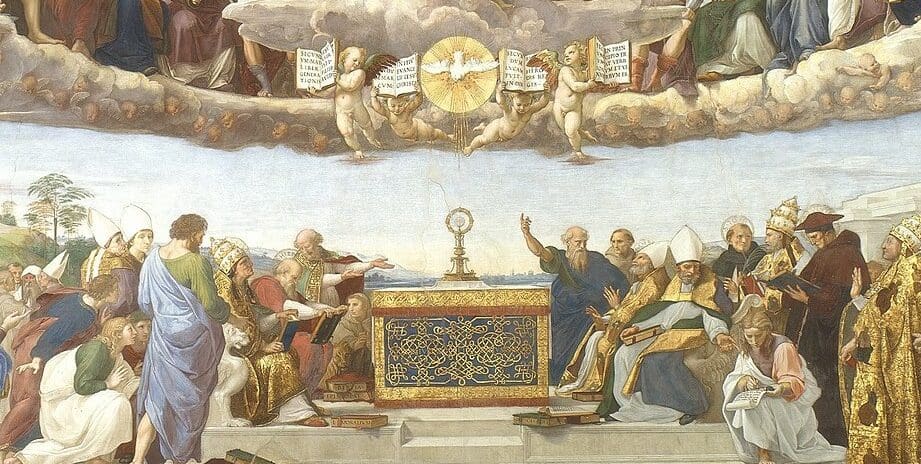

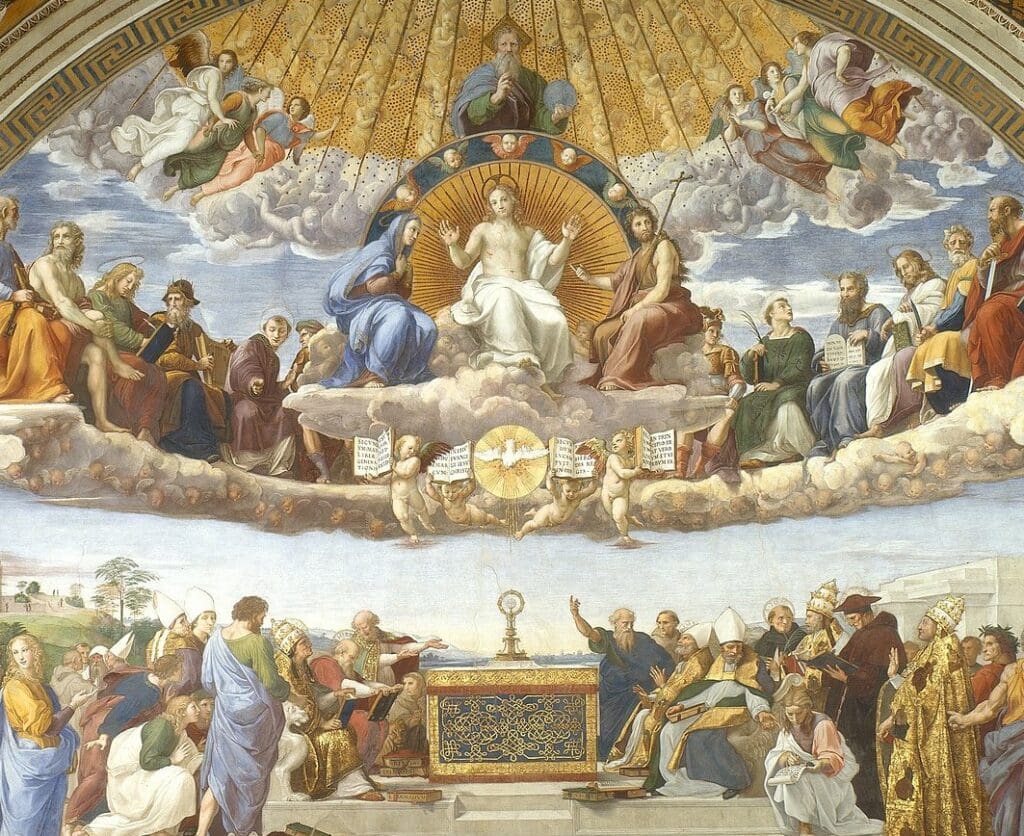

Image Source: AB/The Disputation of the Holy Sacrament (1509–1510), cropped, by Raphael

Footnotes

- S. Athanasius, “Athanasius’ Letter to Adelphus,” in Later Treatises of S. Athanasius, Archbishop of Alexandria, with Notes; and an Appendix on S. Cyril of Alexandria and Theodoret (London: James Parker and Co.; Rivingtons, 1881), 68: Ath., Ep. Adelph. 6.

- Khaled Anatolios, Retrieving Nicaea: The Development and Meaning of Trinitarian Doctrine (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2011), 37.

- Robert Louis Wilken, The Spirit of Early Christian Thought: Seeking the Face of God (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 27. Cf. S. Irenaeus Bishop of Lyons, Five Books of S. Irenaeus against Heresies, trans. John Keble, A Library of Fathers of the Holy Catholic Church (Oxford: James Parker and Co.; Rivingtons, 1872), 360: Iren., Adv. Haer. 4.18.4.

- S. Athanasius, “Athanasius’ Letter to Adelphus,” in Later Treatises of S. Athanasius, Archbishop of Alexandria, with Notes; and an Appendix on S. Cyril of Alexandria and Theodoret (London: James Parker and Co.; Rivingtons, 1881), 68: Ath., Ep. Adelph. 3.

- Ludwig Ott, Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma, trans. P. Lynch, rev. R. Fastiggi (London: Baronius Press, 2018), 158.

- Joseph Pohle and Arthur Preuss, Christology: A Dogmatic Treatise on the Incarnation, Dogmatic Theology (St. Louis: B. Herder, 1913), 284.

- James T. O’Connor, The Hidden Manna: A Theology of the Eucharist (Second Edition; San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2005), 33. Cf. The Works of Saint Cyril of Jerusalem, ed. Bernard M. Peebles, trans. Leo P. McCauley and Anthony A. Stephenson, vol. 64, The Fathers of the Church (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1970), 203: Cyr. Hier., Cat. Lect. 23.21.

- O’Connor, The Hidden Manna, 226.

- O’Connor, 46. Cf. John Chrysostom, “Homily LXXXII,” in The Homilies of S. John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople, on the Gospel of St. Matthew, A Library of Fathers of the Holy Catholic Church (Oxford; London: John Henry Parker; F. and J. Rivington, 1851), 1091.

- In 1 Cor. Hom. xxiv. 5, from Darwell Stone, A History of the Doctrine of the Holy Eucharist (London: Longmans, Green, 1909), 107. Cited in Benedict J. Groeschel and James Monti, In the Presence of Our Lord: The History, Theology and Psychology of Eucharistic Devotion (Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor, 1997), 179.

- Saint Augustine, Expositions of the Psalms 73–98, ed. John E. Rotelle, trans. Maria Boulding, vol. 18 of The Works of Saint Augustine: A Translation for the 21st Century (Hyde Park, NY: New City Press, 2002), 474–475.

- The Works of Saint Cyril of Jerusalem, ed. Bernard M. Peebles; trans. Leo P. McCauley and Anthony A. Stephenson; vol. 64; The Fathers of the Church (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1970), 203: Cyr. Hier., Cat. Lect. 23.22.

- O’Connor, The Hidden Manna, 79, n117.

- Saint Gregory Nazianzen, “On His Sister, Saint Gorgonia,” in Funeral Orations, trans. Leo P. McCauley et al., vol. 22, The Fathers of the Church (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1953), 113–114: Greg. Naz., Orat. 8.18.

- Benedict J. Groeschel and James Monti, In the Presence of Our Lord: The History, Theology and Psychology of Eucharistic Devotion (Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor, 1997), 185.

- R. Ronzani, “Presanctified” eds. Angelo Di Berardino, Thomas C. Oden, and Joel C. Elowsky. The Encyclopedia of Ancient Christianity (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2014) 297.

- Groeschel and Monti, In the Presence of the Lord, 189.

- Andrew Louth, Introducing Eastern Orthodox Theology (London: SPCK, 2013), 110.

- Hermann Sasse, This Is My Body: Luther’s Contention for the Real Presence in the Sacrament of the Altar (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2001), 15.

- John Damascene, Writings, ed. Hermigild Dressler, trans. Frederic H. Chase Jr., vol. 37 of The Fathers of the Church (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1958), 358: De Fide Orth. 4.13. Cited in Darwell Stone, A History of the Doctrine of the Holy Eucharist (London: Longmans, Green, 1909), 146.

- SeeArcher St. Clair Harvey, “Pyxis,” The Eerdmans Encyclopedia of Early Christian Art and Archaeology (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2017), 376.

- Groeschel and Monti, In the Presence of the Lord, 191. See also, Vladimir Baranov, “Constructing the Underground Community: The Letters of Theodore the Studite and the Letter of Emperors Michael II and Theophilos to Louis the Pious,” Scrinium: Revue de Patrologie, D’hagiographie Critique et D’histoire Ecclésiastique: Patrologia Pacifica Secunda 6 (2010): 246–259.

- Groeschel and Monti, In the Presence of the Lord, 191–192.

- Groeschel and Monti, In the Presence of the Lord, 250.

- Josef Jungmann SJ, The Place of Christ in Liturgical Prayer, (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1989), 259. Cited in Groeschel, In the Presence of Our Lord, 191–92.

- Nathan Mitchell, Cult and Controversy: The Worship of the Eucharist Outside Mass (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1980) 48.

- O’Connor, The Hidden Manna, 187.

- Mitchell, Cult and Controversy, 116.

- Stone, A History of the Doctrine of the Holy Eucharist, 250.

- Stone, A History of the Doctrine of the Holy Eucharist, 249.