Jesus’ post-Resurrection engagement with his disciples on the road to Emmaus presents us with a perpetually valid model for Eucharistic revival.1 In light of recent appeals by the bishops of the United States for such a revival, I would like to introduce some insights from patristic, medieval, and modern exegesis of this Gospel episode (Luke 24:13-35) that suggest orientations for fruitful renewal. My hope is that by considering how Jesus Christ once opened the eyes of his disciples, we can learn how to see him more clearly ourselves and better cooperate with him in promoting Eucharistic renewal in the Church.

State of the Disciples

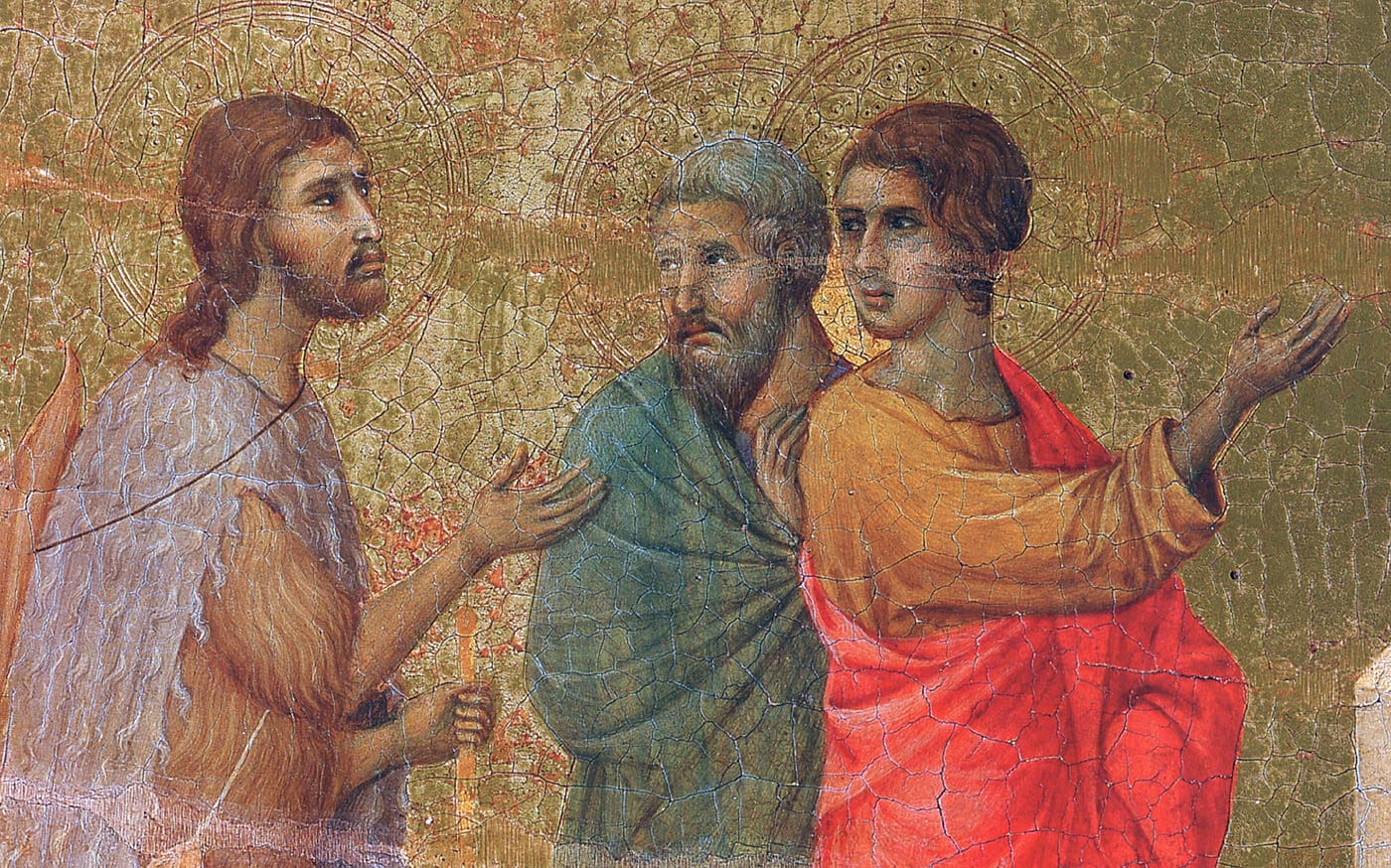

The narrative opens with two disciples travelling away from Jerusalem. Not only was Jerusalem the nexus of Jewish religion, but the Apostles are also gathered in Jerusalem, and so these disciples are distancing themselves from the apostolic community. Even more importantly, their journey takes place “that very day”—that is, on the day of Christ’s resurrection. Although the Gospels highlight the agility of Christ’s resurrected body, which limits what we can conclude about his physical location at various times, nonetheless, the inspired author implies that by departing from Jerusalem on Easter Sunday, these disciples are moving away from the resurrected Christ.

One might object that the disciples’ geographical route is irrelevant, but we quickly learn about their interior state, which confirms that their direction is a symptom of a deeper spiritual disorder. We are introduced to this disorder first through its effect: “While they were talking and discussing together, Jesus himself drew near and went with them. But their eyes were kept from recognizing him.” St. Mark summarizes the whole episode: “he appeared in another form to two of them, as they were walking into the country” (Mark 16:12). Based on this summary alone, we might conclude that the disciples’ inability to recognize Christ was a natural consequence of their not having previously seen anyone of this “appearance,” but the Fathers of the Church knew that some ratio was necessary to explain Christ’s appearing differently, to avoid implicating him in deception; there must have been something in the disciples in need of correction that justified his appearing in a different way.2 St. Gregory explains that Christ “was a stranger to faith in their hearts,” and accordingly he “showed himself in body such as he was in their minds.”3

The inspired author implies that by departing from Jerusalem on Easter Sunday, these disciples on the road to Emmaus are moving away from the resurrected Christ.

St. Augustine likewise attributes the disciples’ inability to recognize Christ to a deficiency in their faith. After joining them on the way, Jesus “said to them, ‘What is this conversation which you are holding with each other as you walk?’ And they stood still, looking sad.” They report that they were discussing the things “concerning Jesus of Nazareth, who was a prophet mighty in deed and word before God and all the people.” St. Augustine observes that they designate Jesus merely as a prophet, and no longer as the Christ and the Son of God; hence they have abandoned genuine Christian faith.4

We also learn about another spiritual disorder connected to their lapse in faith and despondency, namely, despair. They confess that “our chief priests and rulers delivered him up to be condemned to death, and crucified him. But we had hoped that he was the one to redeem Israel.” By admitting that “we had hoped,” they reveal that they no longer have hope.5

Jesus’ death was therefore a scandal to them. The anonymous author of an ancient Christian text long attributed to St. Cyprian proposes that many Jews were convinced that the Christ would not die. He argues this based on the Jewish crowd’s response to Jesus’ prediction of his crucifixion: “‘when I am lifted up from the earth, I will draw all men to myself.’ He said this to show by what death he was going to die.…The crowd answered him, ‘We have heard from the Law that the Christ remains forever. How can you say that the Son of Man must be lifted up?’” (John 12:32-35). Accordingly, Pseudo-Cyprian explains about the two disciples that Christ’s “death had so offended them that they did not believe him to have risen again whom they [thought and] implied ought not to have died.”6 Jesus’ response to the two disciples confirms this interpretation: “O foolish men, and slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken! Was it not necessary that the Christ should suffer these things?” Thus, Jesus identifies the inadequacy of his disciples’ faith—which prevented them from believing in his resurrection and also from recognizing him—precisely on the grounds that they had intentionally overlooked or misinterpreted the prophesies about his sufferings.

Restoration

These two disciples typify Christians today for whom the bishops are concerned in calling for Eucharistic revival. A growing number of American Catholics are absenting themselves from Sunday Mass, just as the disciples on the road departed from the community of the Apostolic Church on the day of the Lord’s resurrection. Relatedly, a disconcerting number of Catholics do not profess faith in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, which suggests a lack of spiritual perception akin to that of the disciples who could not recognize the risen Lord appearing to them in a different form on the road. Without issuing judgments about the moral state of disenfranchised Catholics today, it is certainly conceivable that these have also lost both theological faith and hope and correspondingly live in sadness and despondency, like the disciples on the road. (Perhaps we ourselves are also imperfect in faith, hope, and seeing the Lord as we should.)

The good news is: if the two disciples in our narrative have a spiritual profile that matches that of many Catholics today, then the saving actions of God revealed in this narrative have prophetic and normative value for us. In other words, we can discover in Jesus’ responses to the disciples what he is doing now through his Spirit and wishes to accomplish through his Mystical Body in response to the present crisis.

If the two disciples in our narrative have a spiritual profile that matches that of many Catholics today, then the saving actions of God revealed in this narrative have prophetic and normative value for us.

Attentive to Jesus’ mercy and pastoral wisdom revealed in this Gospel pericope, Archbishop Samuel Aquila of Denver beautifully summarizes the Lord’s approach to the wayward disciples: “He chooses to first listen to them and allow them to articulate where they had strayed. He then shares and initiates them into his own worldview through the scriptures.”7 According to the narrative, after affirming the necessity that the Christ “should suffer these things and enter into his glory,” then “beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them in all the scriptures the things concerning himself.” St. Justin Martyr, as well as the fourth-century apologist Lactantius, encapsulate Jesus’ entire post-Resurrection ministry prior to his Ascension in terms of opening the Scriptures.8 This is expressed symbolically in the Apocalypse: “the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, has conquered, so that he can open the scroll…. And between the throne and the four living creatures…I saw a Lamb standing, as though it had been slain…and they sang a new song, saying, ‘Worthy are you to take the scroll and to open its seals, for you were slain, and by your blood you ransomed people for God’” (Revelation 5:5-9). The Lion-Lamb, the crucified and risen Christ, does not merely offer a conceptual key for the interpretation of the Scriptures, but he himself, crucified and risen, interprets the Scriptures. Thus, for the early Church, it is precisely in the light of the resurrected Christ and through his activity that the Scriptures can be rightly understood.

St. Thomas Aquinas follows the consensus of the Fathers in affirming the death and resurrection of Jesus as the key to unlocking the Scriptures and by presenting Christ himself as the inaugurator of this interpretive method. In fact, St. Thomas considers the Christological interpretation of Scripture so essential that he speaks of it as constituting Christian discipleship: commenting on the “chair of Moses” mentioned in the Gospel of Matthew, he writes, “on the chair sit…the scribes, who consider only the letter [of the Scriptures]; the Pharisees, who consider a small part of its interior sense; [and] the disciples of Christ, who ponder the whole. And they are not called disciples of Moses, but of Christ. [As it says:] … he interpreted to them in all the scriptures the things concerning himself.”9 In other words, for St. Thomas, to be a disciple of Christ means precisely to learn from Christ, who interprets all of the Scriptures in light of himself.10

Most importantly, St. Thomas hints at the reason for the connection between Christ’s Passion and the opening of the Scriptures. He comments on Psalm 22, which Christ invoked on the Cross, and which includes the line “my heart is like wax; it is melted within my breast.” St. Thomas proposes: “this liquefaction [or melting] can be applied to Christ…for this liquefaction is from the Holy Spirit and is in the…affections.” He then offers another interpretation: “by the heart of Christ should be understood the Sacred Scriptures which manifest the heart of Christ. This was closed before the Passion, since it was obscure, but is open after the Passion.”11 If we take both of these interpretations together, we arrive at the following conclusions. Christ’s heart on the Cross was so inflamed with love from the Holy Spirit that he declared that it was melted. The Scriptures, for their part, manifest the heart of Christ, which is full of this love that he displayed on the Cross. Thus, it is only in light of the Cross that the essential meaning of the Scriptures is revealed. Conversely, the meaning of the Scriptures is nothing other than the love of Christ revealed on the Cross. For a Christian, therefore, the study of the Scriptures and the study of the Cross are inseparably the study of the heart of Christ filled with love. To read Sacred Scripture apart from Christ and his Passion, therefore, is to inevitably fail to attain understanding of the most essential meaning of the text. When the heart of Jesus was pierced on the Cross, manifesting his boundless love, the Scriptures were definitively opened.

The Fire of the Word

Not surprisingly, the disciples “said to each other, ‘Did not our hearts burn within us while he talked to us on the road, while he opened to us the scriptures?’” The Fathers interpret this burning as a fire of love;12 and likewise in the lives of the saints, the extraordinary mystical phenomenon of burning in the heart is associated with excessive love.13 Nonetheless, we should pause to consider how the disciples would have understood this experience, since they appeal to it as though it should have been for them a sufficient proof of the Lord’s resurrection.

It is only in light of the Cross that the essential meaning of the Scriptures is revealed.

On the one hand, the disciples may have recalled listening to Jesus on previous occasions. A distinctive effect of the divine Word is that it communicates the Spirit. St. Thomas writes: “the Son is sent…according to the intellectual illumination, which breaks forth into the affection of love, as is said…In my meditation a fire shall flame forth.”14 And so, perhaps these disciples, reflecting on the breaking forth of the fire of love in their hearts that resulted from this Mysterious Man’s teaching, recognized an effect in themselves that they had previously experienced only from Jesus of Nazareth, whom they should have realized by this very fact was teaching them again in person and therefore must have risen from the dead.

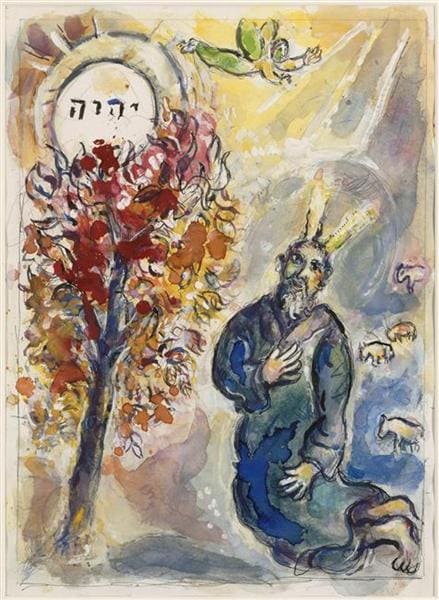

On the other hand, it seems significant that the disciples do not specify that their hearts were burning with love but only report that their hearts were burning, as if the experience of fire alone was sufficient to indicate the resurrection. We are perhaps too quick to associate fire with love, without adequately considering what the perception of an extraordinary fire would have meant for first-century Jewish Christians. Specifically, the Dictionnaire de Spiritualité relates: “in the religion of Israel, fire is the preeminent sign of the divine presence. It is generally the principal element of theophanies or manifestations of God on the earth.”15 This is easy to confirm: fire had a conspicuous place in the great theophanies to Moses, Isaiah, Ezekiel, etc.

The question immediately arises, however: why does the spiritual interpretation of Scripture have the effect of an interior theophany? St. Thomas offers a clue in the first question of the Summa: “The author of Holy Scripture is God, in whose power it is to signify his meaning, not by words only…but also by things themselves.”16 When Scripture is understood Christologically, that is, in its unity, two things are made clear: first, that God must be the Author of the Scriptures, since only divine omniscience can be the source of prophetic knowledge of the future; second, God must be the Author of the historical events recorded in the Scriptures, since only divine omnipotence can direct being itself to signify truth. And so, the typological interpretation of Scripture—or demonstrating the fulfillment of Biblical prophecy—necessarily manifests the Author of the Scriptures as the Lord of history, who both transcends history by his infinite knowledge and power, and who also acts intimately within history on the level of being and human knowledge.

Furthermore, since Sacred Scripture centers on Jesus Christ, who is the very transcendent Lord who entered history personally in order to reveal through his sufferings on the Cross the love that is the source of creation, there is no greater manifestation of the true God possible through the mere signification of words than interpreting the inspired Scriptures in light of the death and resurrection of Christ. Once again, it is no surprise that the disciples’ hearts were burning! In all the theophanies of the Old Covenant, material fire was ultimately a sign of the spiritual fire that would burn first of all in the heart of Christ on the Cross and then in the hearts of those disciples who were introduced by him into this very truth.

Transformed Hearts

The Fathers, when discussing the fire ignited in the disciples’ hearts, emphasize the transformative effect of God’s Word. St. Athanasius, for example, writes that “our Lord Jesus Christ…came that he might cast this [fire] upon earth…so that the soul, being purified, might be able to bring forth fruit.”17 St. Jerome asks, “Where should we seek this saving fire?” and concludes: “No doubt in the sacred volumes, reading from which all vices are purged.”18 St. Augustine argues that the fire which Christ came to set on the earth was himself, the Word of God, a consuming fire, “for the love of God consumes our old life and renews our being.”19

Even though the disciples experience a fire of love that evidences the presence of God in the risen Christ, they do not yet identify him. Still, his transformative word has a decisive effect on their dispositions and actions: “they drew near to the village to which they were going. He appeared to be going further, but they constrained him, saying, ‘Stay with us…So he went in to stay with them.” Archbishop Aquila comments, “When we genuinely love someone, we do not want to leave them or them to leave us.”20

The Catechism of the Catholic Church defines the human heart as “our hidden center, beyond the grasp of our reason…. The heart is the place of decision.”21 The fact that Christ’s interpretation of Scripture generated a fire in their hearts that issued in changed behavior means that the principal work of their conversion has been accomplished. The disorder of disbelief (and despair) that previously reigned in their hearts due to the false interpretation of God’s plan for history—on account of which they formerly could not recognize the risen Christ—was corrected through his teaching, such that they are now disposed to recognize him. And this is what occurs next: “when he was at table with them, he took the bread and blessed, and broke it, and gave it to them. And their eyes were opened and they recognized him.”

Christ’s repeating for these disciples what he did at the Last Supper was the final step in their coming to recognize him.22 They must have perceived the intrinsic relation of the Eucharist with Christ’s Passion, which it signified, and which they now properly understood in light of the Scriptures. And so, they report to the Apostles that “he was known to them in the breaking of the bread.” It is noteworthy that among the actions of taking, breaking, blessing, and giving, they chose breaking to refer to the crucial moment. This conveys most clearly the connection that Christ himself established between this Sacrament and his sacrificial death when he said, “take this all of you and eat of it, for this is my body, which will be given up for you.”

Immediately upon recognizing him, “he vanished from their sight.” Christ was teaching the disciples that he is truly present in this Sacrament. It is as if he was playing a game of peek-a-boo—disappearing in one form to foster recognition of himself in another form—treating the disciples as spiritual children, giving them a lesson in “supernatural object permanence.” The Real Presence is a doctrine about which the disciples needed to be convinced, because this is the manner in which he would remain substantially present to the Church on earth after his ascension. He does not permit the disciples even a moment to rest in the sensible enjoyment of his glorified body: he immediately departs, leaving a strong impression linking his risen presence with this sacrament.

It is noteworthy that among the actions of taking, breaking, blessing, and giving, the disciples chose breaking to refer to the crucial moment. This conveys most clearly the connection that Christ himself established between the Eucharist and his sacrificial death.

We should also notice that this narrative presents the Sacrament in relation to the resurrection. Not only is Christ known to be present in the Eucharist, but above all the Eucharist makes known his risen presence: “He was known to them in the breaking of the bread.” This corresponds to the central point of the narrative, which possesses a clearly chiastic structure.23 The sacred author’s presentation of the Emmaus story, which takes place on Easter Sunday, focuses on the announcement of the resurrection by the women: “they had even seen a vision of angels, who said that he was alive.” The truth about the Sacrament is therefore contextualized: above all, the disciples identify the person of Jesus of Nazareth, who is alive, and who communicates himself through both word and Sacrament.

Authentic love is never inactive, and, accordingly, the two disciples “rose that same hour and returned to Jerusalem…and they found the eleven gathered together…. Then they told what had happened on the road.” Archbishop Aquila observes that “they immediately go and witness to their experience of the Risen Christ. They go on mission.”24 We should add that the disciples specifically seek the Apostles, and so their knowledge and love of the risen Christ leads them to apostolic communion.

Orientations

To the many proposals for fostering Eucharistic revival, I only wish to add a few in light of this Gospel pericope. First of all, we can imitate Christ who travels with discouraged and disbelieving disciples and attentively listens to their concerns.

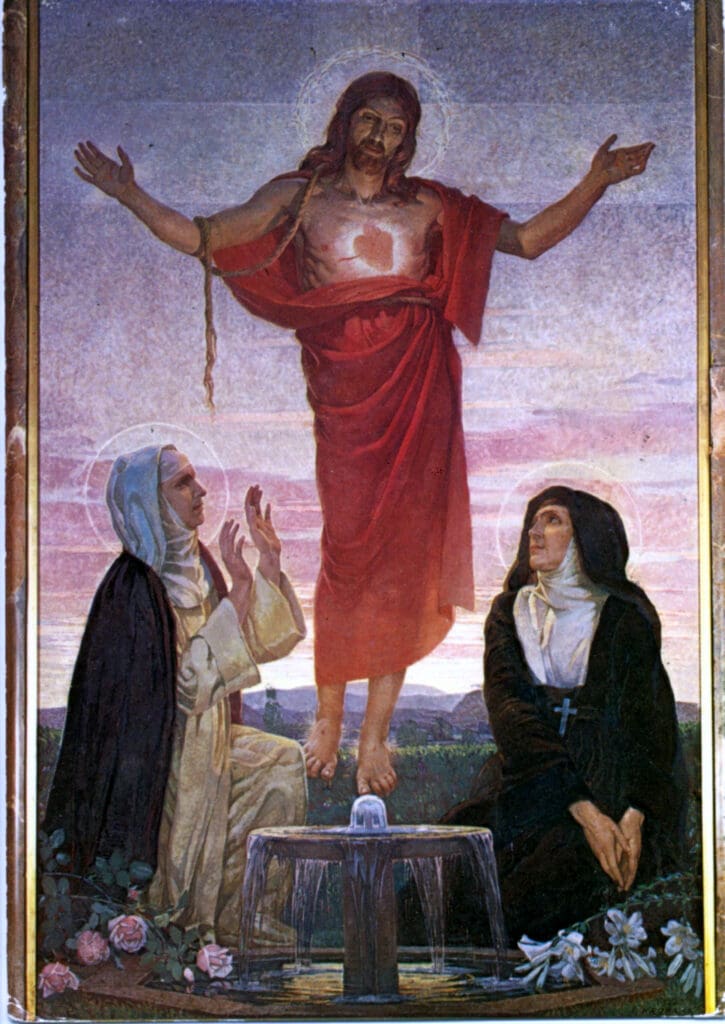

Second, we can emphasize the redemptive death of Jesus Christ. To the degree that we are ignorant of the love of Christ manifested in his death on the Cross, we cannot understand the meaning of the Eucharist, which represents this sacrifice. In the 17th century, it was precisely to counteract indifference and ingratitude toward himself in the Holy Eucharist that Jesus enjoined devotion to his Sacred Heart, directing the world to “Behold…this Heart which has so loved men that it has spared nothing, even to exhausting and consuming itself, in order to testify its love.”25

Third, we should principally proclaim the resurrection of Jesus Christ. Faith in the Eucharist depends on belief in the divinity of Christ, which was most clearly manifested in his resurrection.26 And celebration of this Sacrament does not commemorate a mere prophet who died but deepens communion with the living God in the person of the risen Lord Jesus.

Faith in the Eucharist depends on belief in the divinity of Christ, which was most clearly manifested in his resurrection.

Fourth, we should return to announcing Jesus Christ as the fulfillment of prophecy and the primary typological referent of Scripture. This was the method that Christ himself used in order to dispose his disciples to recognize himself, and it was accordingly the method of the Fathers.27 Typological teaching manifests the divine presence, precisely in Jesus; and through his being revealed as the center of the divine plan, he appears as the destiny of every human person. The Fathers emphasize the transformative power of the Scriptures, which cause the human heart to burn with desire to be with the Lord. Without handing on the truth about Christ that is conveyed in the Scriptures, we should not expect any conversion toward the Eucharist. I could announce the real presence of my friend Tom in the next room until I am blue in the face, but I should not expect anyone to visit the next room who lacks personal knowledge of him. Through the opening of the Scriptures, the heart of Christ in the Eucharist is revealed as the heart of God who is love, and the natural outcome is increased devotion to the Eucharist.

Finally, we should pray for illumination. The disciples on the road suffered from insufficient spiritual perception. St. Thomas Aquinas, in his treatment of the Holy Spirit’s gift of understanding, explains that “there are many kinds of things that are hidden within;” for example, “under words lies hidden their meaning” and “under the accidents lies hidden the nature of the substantial reality.”28 Inasmuch as the gift of understanding enables us to perceive the mystical sense of the words of Scripture that disclose Christ and the substantial reality of his presence hidden under the accidents of bread and wine, we ought to pray for the whole Church, that God would strengthen our minds with the light of understanding to know the risen Christ. “For it is God who said, ‘Let light shine out of darkness,’ who has shone in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Christ” (2 Corinthians 4:6).

Joshua Revelle is an Assistant Professor of Dogmatic and Spiritual Theology at St. John Vianney Theological Seminary in Denver, CO. He holds a BA and MA from Franciscan University of Steubenville, OH, and a PhD from The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C.

Footnotes

- As an introduction to the Church’s Year of the Eucharist in 2004, Pope St. John Paul II presented “the image of the disciples on the way to Emmaus…as a fitting guide for…when the Church will be particularly engaged in living out the mystery of the Holy Eucharist.” John Paul II, Apostolic Letter “Mane Nobiscum Domine,” https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_letters/2004/documents/hf_jp-ii_apl_20041008_mane-nobiscum-domine.html. More recently, for the launch of the diocesan phase of the Eucharistic revival in the United States, Archbishop Samuel Aquila offered a similar recommendation and his own reflections on the Gospel pericope. Samuel Aquila, Advent 2022 Pastoral Note “Were Not Our Hearts Burning,” https://archden.org/pastoral-notes/advent-2022-were-not-our-hearts-burning/

- For example: “The mistake which held them was not to be attributed to the Lord’s body.” St. Jerome, “To Pammachius Against John of Jerusalem,” trans. W. Fremantle, G. Lewis and W. Martley, NPNF, Second Series, vol. 6 (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature, 1893), §35.

- St. Gregory the Great, “Homilia XXIII” in Gregorius Magnus: Homiliae in Evangelia, CCSL, vol. 141 (Turnhout: Brepols, 1999), 194. My translation.

- St. Augustine, “Sermon 236A,” trans. Edmund Hill, WSA, vol. 3/7 (New Rochelle, NY: New City Press), §3.

- St. Augustine, “Sermon 26A,” §4.

- Pseudo-Cyprian, De Rebaptismate, in CCSL, vol. 3F: Sancti Cypriani Episcopi Opera, Pars IV; Opera Pseudo-Cyprianea, Pars I (Turnhout: Brepols, 2016), §9. My translation.

- Aquila, “Were Not Our Hearts Burning.”

- St. Justin Martyr, The First Apology, in Writings of Saint Justin Martyr, trans. Thomas Falls, The Fathers of the Church: A New Translation (New York: Christian Heritage, 1948), chap. 50; Lactantius, The Divine Institutes: Books I-VII, trans. Mary McDonald, The Fathers of the Church: A New Translation (Washington D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1964), 4.20.

- St. Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew, Chapters 13-28, trans. Jeremy Holmes, Latin/English Edition of the Works of St. Thomas Aquinas, vol. 34 (Lander, WY: The Aquinas Institute), par. 1833. Emphasis added; Biblical quotation replaced with ESV.

- In a text that closely resembles the Emmaus road narrative, St. Thomas comments on John 1:26: “there is one standing in your midst i.e., in the Sacred Scriptures…whom you do not recognize, because your heart is hardened by unbelief, and your eyes blinded, so that you do not recognize as present the person you believe is to come.” St. Thomas explicitly links unbelief in the heart, blindness preventing recognition of Jesus, and the failure to interpret the Scriptures with respect to him. St. Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on the Gospel of John: Chapters 1-5, trans. Fabian Larcher (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 2010), §246.

- St. Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on Psalms, trans. Sr. Albert Marie Surmanski and Sr. Maria Veritas Marks, in Commentary on the Psalms, Rigans Montes, Hic est Liber, Latin/English Edition of the Works of St. Thomas Aquinas, vol. 29 (Green Bay, WI: Aquinas Institute, 2021), §186. Emphasis removed; translation slightly amended.

- Origen, Second Homily [on the Song of Songs], trans. R. P. Lawson, in Origen: The Song of Songs, Commentary and Homilies, Ancient Christian Writers, vol. 26 (Westminster, MD: Newman Press, 1957), §8; St. Ambrose, Isaac, or the Soul, in St. Ambrose: Seven Exegetical Works, The Fathers of the Church: A New Translation (Washington, D.C. The Catholic University of America Press, 1972), 8.77; St. Thomas Aquinas, The Commandments of God, trans. Laurence Shapcote (London: Burns, Oates & Washbourne), prol.

- Jordan Aumann, Spiritual Theology, (London: Sheed & Ward, 1982), 431. For many examples, see Herbert Thurston, The Physical Phenomena of Mysticism, ed. J. Crehan (London: Burns Oates, 1952), chap. 8, “Incendium Amoris.”

- St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province, 3 vols. (New York: Benziger Brothers, 1947), I, q. 43, a. 5, ad. 2.

- Friedrich Zoepfl, “Feu,” in Dictionnaire de Spiritualité, vol. 5 (Paris: Beachesne, 1964), col. 247. My translation.

- St. Thomas, ST I, q. 1, a. 10, co. Translation amended.

- St. Athanasius, “Letter III,” trans. R. Payne-Smith, NPNF, Second Series, vol. 4 (New York: Christian Literature, 1892), §4.

- St. Jerome, “Epistula XVIIIA Ad Damasum,” in Sancti Eusebii Hieronymi Epistulae, Pars I, CSEL (Vindobona: Tempsky, 1910), §6. My translation. He also recommends the reading of Scripture since the fire of love that it generates replaces sensual desire; St. Jerome, “Letter XX,” NPNF, vol. 6, §17.

- St. Augustine, Answer to Adimantus, WSA, vol. 1/19, 13.3.

- Aquila, “Were Not Our Hearts Burning.”

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, no. 2563.

- It is not clear whether these disciples had heard about the institution of the Eucharist from the Apostles during the previous day or two—nor how their memory was involved in this stage of the process of recognition.

- John Noland, Word Biblical Commentary, vol. 35c (Dallas: Word Books, 1993), 1177-8. Some examples of the nested parallels include: the disciples speak with one another in verses 14 and 32; their eyes are closed, then opened in verses 16 and 31; they recall the “things concerning Jesus,” and Jesus explains “the things concerning himself” in verses 19 and 27; Christ’s sufferings are discussed in verses 20 and 25; his tomb is mentioned in 22 and 24; etc. These center on the announcement of his resurrection.

- Aquila, “Were Not Our Hearts Burning.”

- Bougaud, Revelations of the Sacred Heart to Blessed Margaret Mary, and the History of Her Life, trans. A Visitandine of Baltimore, 2nd ed. (New York: Benziger Brothers, 1890), 176.

- That Eucharistic belief corresponds to faith in the divinity of Christ, see for example John 6:68-69: after many disciples depart from Christ on account of his teaching about the Bread of Life, St. Peter responds with a profession of faith in Christ, “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life, and we have believed, and have come to know, that you are the Holy One of God.” That Christ’s divinity is manifested especially by his resurrection, see Rom. 1:3-4 and Catechism of the Catholic Church, no. 653.

- The First Vatican Council declared that “miracles and prophecies…demonstrating…the omnipotence and infinite knowledge of God, are the most certain signs of revelation and are suited to the understanding of all.” “Dei Filius–The Dogmatic Constitution on the Catholic Faith,” Nova et Vetera, English Edition, 20, no. 3 (2022): 947 (chap. 3).

- St. Thomas, ST II-II, q. 8, a. 1, co.