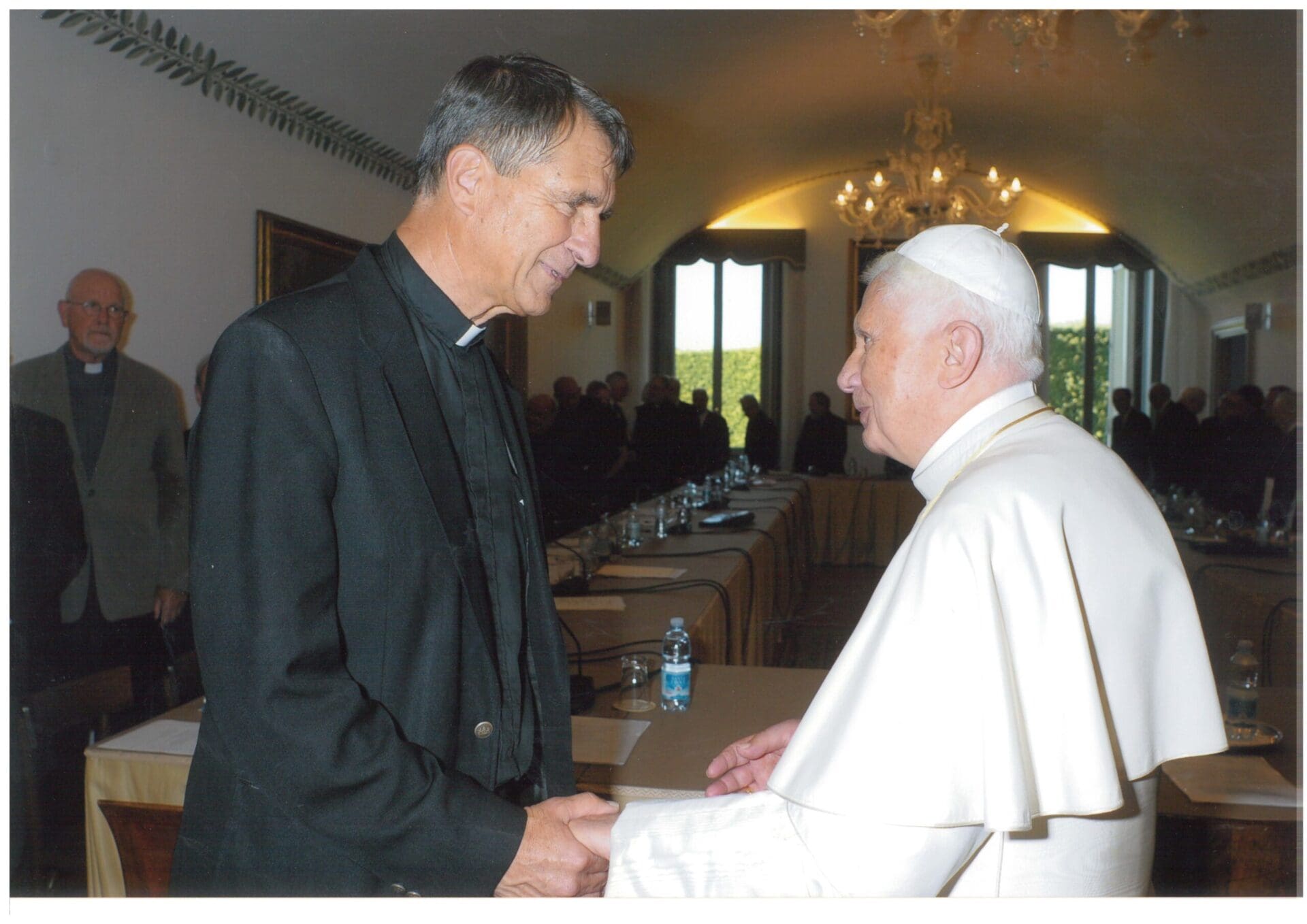

With the passing of Pope Benedict XVI, Adoremus and its supporters have lost one of their founding fathers. Adoremus, now in its 28th year, was in large part founded by the support of then-Cardinal Ratzinger. When Father Fessio, a friend and student of Joseph Ratzinger, first pitched the idea of beginning a liturgical bulletin—one directed not simply to specialists, but to all Catholics interested in celebrating the Church’s liturgical treasure—it was the Cardinal’s response that sealed the deal: “Yes, I agree we need that kind of movement…and I think the time is ripe for the kind of journal you are describing.”

Since then, Adoremus has gladly followed the liturgical insights of Joseph Ratzinger—first as Cardinal, then as Pope—and promoted his vision of the sacred liturgy. Indeed, one of Adoremus’s founding principles rests upon a short excerpt of this 1986 work, Feast of Faith: Approaches to Theology of the Liturgy: “What is exciting about Christian Liturgy is that it lifts us up out of our narrow sphere and lets us share in the Truth. The aim of all liturgical renewal must be to bring to light this liberating greatness” (p.75).

Not all in the Church, of course, shared such a liturgical vision. Some may wonder, in fact, if such a broad liturgical perspective is relevant today. Can the cares and concerns surrounding the sacred liturgy in 2023 find any solution in a claim from 1986, or a liturgical review founded in 1995, or a Pope whose office ended in 2013?

Much has been written on the liturgical legacy of the late Pope Benedict, from his introduction of the now-eponymous (i.e. “Benedictine”) altar arrangement, to encouraging an interpretation of Sacrosanctum Concilium in continuity with the longer tradition, to the mutual enrichment of liturgical forms in Summorum Pontificum. Each of these instances (and more) exemplify the long-view of the liturgy—and this is a perspective as necessary now as ever.

Consider Ratzinger’s statement cited above: “What is exciting about Christian Liturgy….” What, indeed, is so exciting about it? Most stories today, unfortunately, have little to do with liturgical “excitement” and more to do with liturgical discord and division. The Cardinal continues: liturgy “lifts us up out of our narrow sphere.” Here, too, the liturgical discussions of the day often limit themselves to the “narrow sphere” of ritual forms—books (2002 or 1962?), language (Latin or vernacular?), or law (such as a bishop’s authority to regulate particular liturgical practices).

On the contrary, says Ratzinger, “the aim of all liturgical renewal must be to bring to light [the liturgy’s] liberating greatness.” Speaking personally, far too much of my liturgical energy is mired in anxiety, conflict, and minutiae—hardly “liberating greatness.”

In short, much of the modern liturgical movement and of the Church’s liturgical apostolate is lost in the proverbial trees, with the larger liturgical forest long invisible. And it is for this reason that Cardinal Ratzinger’s long view of history and tradition—as well as it’s forward-looking and eschatological vision—is needed today.

Such a correction cannot, of course, ignore the immediate issues of our time. Much as revelation takes the form of written texts, so the Paschal sacrifice of Christ exists today as liturgical ritual. Consequently, ritual forms—old and new, Latin and vernacular, local and universal, “gathering songs” versus “entrance chants” (see “Gathering Song” or “Entrance Chant”: What’s in a Name?)—are entirely significant. These ritual details are the tangible locus where heaven meets earth. Still, it is only within the larger liturgical vision (Thank you, Pope Benedict!) that liturgical details gain significance. As I have remarked previously in my Bulletin editorials, too much energy is spent in the wrong places: if I were as eager about my divinization as the latest news analysis, I could truly be “excited” to escape my “narrow sphere,” “share in the Truth,” and experience the “liberating greatness” the Church’s liturgy has to offer.

But maybe such a vision is unrealistic in this fallen world. It was, after all, Ratzinger’s own observation that we’re still in a wounded world and living among the shadows: that heavenly Temple in which we wish to abide in today’s liturgy is “still under construction” (The Spirit of the Liturgy, 64). What, then, shall we do?

Here, as elsewhere in the liturgical world, opinions differ—and perhaps they must. For one, none of us (save God) has any idea what tomorrow’s magisterial direction might bring. For another, each of us lives in rather different circumstances with varying liturgical experiences and needs: my small parish in rural Wisconsin differs from the convent in New Mexico which, in turn, is unlike the liturgy at St. Mary Cathedral in Sydney, Australia. Still, while much varies and remains unknown, sound principles do exist for the future of the reform of the sacred liturgy. On this point, I am grateful that Adoremus’s original mission, goals, and principles remain as firm as ever.

As Adoremus’s editor, I will read these from time to time; and I encourage you, our readers, to do the same (see The Mission, Goals, and Principles of Adoremus). Jesuit Father Joseph Fessio, Father Jerry Pokorsky, and Helen Hull Hitchcock have built Adoremus on solid ground. So, too, has Joseph Ratzinger blessed Adoremus with insights that have guided us from the start and that will help us see clearly amidst the liturgical uncertainty in the future. If we adopt this long view, excitement, Truth, liberation, and greatness await.