In part I of this article (March 2022), we explored Pope Benedict’s analysis of the state of the liturgy leading up to the Second Vatican Council, his views of the Second Vatican Council’s liturgical reform, and his critique of certain trends and developments in the postconciliar era. In this article, we will study Ratzinger’s solutions to these challenges, known as the “reform of the reform,” and conclude by surveying the liturgical renewal he ushered in during his papacy.

Ratzinger’s “Reform of the Reform”

Ratzinger’s solution to the post-conciliar liturgical crisis is often called a “reform of the reform,” a term whose origin is difficult to trace but has been used by Ratzinger himself to describe his project. At the heart of Ratzinger’s solution to these issues is a proper hermeneutic or lens of interpretation for the Second Vatican Council since the interpretation of Vatican II determines to a great extent the practice of the liturgy. If the Council is imagined as a break in the Church’s history, then the reformed liturgy is seen as a break with the pre-conciliar liturgy. However, if the Council is seen in substantial continuity with tradition, then the reformed rites which it promulgated will be seen in continuity with the older form of the liturgy. Ratzinger believes, therefore, that traditionalists and progressives make the same error: both view the Council as a break in tradition. Ratzinger highlighted both as a cardinal and as pope that the Council did not represent a rupture, but expressed continuity with the Church’s history: “There is no ‘pre-’ or ‘post-’ Conciliar Church,” he writes “There is but one, unique Church that walks the path toward the Lord….”[1]

More recently we have seen increased attacks on the authority of the Second Vatican Council and its liturgical reforms from a vocal minority of radical traditionalists, particularly online and on social media. This renders the balance, nuance, and pastoral sensitivity of Benedict’s approach very timely.

The incorrect way of interpreting the Council, a hermeneutic of rupture, looks at the Council as ground zero for a new beginning, a revolutionary mentality leading to a view of the liturgy as a new product, a fabricated liturgy that can continually be adapted. A hermeneutic of reform in continuity recognizes the given-not-made quality of the liturgy as part of tradition and our inability to manipulate it according to our arbitrary desires or subjective needs. Note that this is not just a hermeneutic of continuity but “reform” in the spirit of continuity. There can be reform, development, and new clarifications, but these must be in harmony with previous Councils, the magisterium of the Church, and the deposit of faith—it must represent, in other words, an organic development. Nor is it merely going back to before the Council, as if we’re now going to try to put the toothpaste back into the tube. Ratzinger writes:

“If by ‘restoration’ is meant a turning back, no restoration of such kind is possible. The church moves forward toward the consummation of history, she looks ahead to the Lord who is coming. No, there is no going back, nor is it possible to go back. Hence there is no ‘restoration’ whatsoever in this sense. But if by restoration we understand the search for a new balance after all the exaggeration of an indiscriminate opening to the world, after the overly positive interpretations of an agnostic and atheistic world, well, then a restoration in this sense (a newly found balance of orientations and values within the catholic totality) is altogether desirable.”[2]

Traditionalists and progressives make the same error: both view the Council as a break in tradition.

With this guiding hermeneutic of reform-in-continuity in the background, Ratzinger’s project of reforming the reform has both internal and external dimensions; that is, he imagines it both as a renewal of an internal dimension consisting of reeducation and renewed catechesis on the nature and spirit of the liturgy, as well as certain external, visible changes in the way the liturgy is celebrated.[3] However, contrary to some who misinterpret Ratzinger’s priorities, I would like to reaffirm at the outset that for Ratzinger this project is not centered on revising the liturgical books themselves or modifying more superficial changes such as certain prayers, ceremonies, gestures, or customs. Instead, Ratzinger’s reform centers on changing our approach to the liturgical books, changing our minds and hearts towards them and the atmosphere and mentality surrounding their celebration—words that we might associate with the notion of liturgical “renewal” rather than the more external dimensions we might associate with the word “reform.” This renewal does not consist in abandoning the postconciliar form of the liturgy but celebrating it with dignity, solemnity, reverence, and beauty. For this reason, Ratzinger calls for a new liturgical movement, a “movement toward the liturgy and toward the right way of celebrating the liturgy, inwardly and outwardly.”[4]

Among the outward and external improvements, Ratzinger begins by advocating for the elimination of liturgical creativity as a central, guiding liturgical goal. On the one hand, this improvement consists in better catechetical explanations which make absolutely clear that the liturgy is “something other than the invention of texts and rites, that it lives precisely from what is beyond manipulation.”[5] On a more practical level, Ratzinger suggests removing certain phrases in the missal that encourage the priest to use “these or other words,” which can be interpreted as leaving too much freedom for celebrants to alter liturgical texts.

Against the exclusive use of liturgical celebrations celebrated “towards the people,” Ratzinger recommends and encourages celebration ad orientem, towards the East as a symbol of the coming Christ. This turning together of priest and congregation towards the Lord would help to cultivate the Godward orientation of the liturgy and of our lives and serve as an antidote to the notion of a closed-in community gathered for a meal which has afflicted the postconciliar era. With his recommendation, however, Ratzinger shows how he doesn’t simply want to restore a past practice but reform it in a spirit of continuity. He doesn’t advocate that the entire Mass would have to be celebrated ad orientem but only the second half, the Eucharistic liturgy proper, where the priest-celebrant guides the people of God to turn towards the Lord together. However, the first part of the Mass, the Liturgy of the Word, has a proclamatory nature and is still fitting to be celebrated towards the people, versus populum. The preconciliar liturgy was often celebrated as a low Mass with the priest celebrant reading the passages of scripture in a low voice in Latin facing the altar, and Ratzinger viewed this as a deficient practice that was in need of reform.

Ratzinger is also aware of the pastoral difficulties that might accompany celebration ad orientum today. After 50 years of celebrating Mass versus populum, he recognizes the attachment that certain people have to this form and the possible confusion and disruption such an abrupt change could have in the lives of the faithful. For this reason, his own alternative solution has been the introduction of a cross on the center of the altar which can represent a “spiritual East” and orient both priest and people to the true center of the Eucharist celebration, the Cross of Christ. This is consistent with the nature of Ratzinger’s “reform of the reform” as a whole: not as something concerned with dramatic, radical, exterior change, which could possibly further the damage caused by the instability in liturgical practice of the last 50 years, but as a prudent use of legitimate options already present within the current Missal.

Tied with the question of orientation in liturgical prayer, Ratzinger advocates for the reintroduction of certain elements of Latin into the reformed liturgical rites. Once again we find his solution very moderate: he doesn’t advocate for restoration of an entirely Latin liturgy. He recognizes that elements of the Liturgy of the Word are more suitable in the vernacular language, but that the use of Latin in certain parts of the Mass, such as the ordinary (the Gloria, Agnus Dei, etc.), could help emphasize the universal dimension of the Church’s Roman Rite, connecting us with tradition and serving as an antidote to the notion that the liturgy is created by each local congregation. Closely related to this is Ratzinger’s concern for revising the translations of the missals into vernacular languages so that they more faithfully reflect the Latin originals and reflect a liturgical language that is more dignified, solemn, and beautiful. Both of these suggestions reflect Ratzinger’s theology of active participation, which doesn’t rely on everything being simple and immediately intelligible or accessible and understood by everyone. Rather, Latin texts and faithful liturgical translations can still move people through their beauty, and cultivate a spiritual attitude of adoration and prayerful communion to facilitate a true internal participation in the liturgical action.

Latin texts and faithful liturgical translations can still move people through their beauty, and cultivate a spiritual attitude of adoration and prayerful communion to facilitate a true internal participation in the liturgical action.

In addition, Ratzinger consistently has recommended the retrieval of certain devotional forms in the Church’s life outside of the Eucharist, such as the Rosary, the Stations of the Cross, the Corpus Christi procession, and Eucharistic adoration. He lamented that many of these devotional forms fell out of practice in the immediate postconciliar period and contributed to the sense that Vatican II was a dramatic break with the past. While the Council reclaimed the fact that the Eucharist was the source and center of the Church’s life and recovered the notion that the assembly should be participating in the liturgical act rather than their private devotions during Mass, Ratzinger believes devotions outside of the Eucharist have the profound capacity to lead us into a more fruitful celebration of the sacraments and help meet the profound spiritual hunger of our modern world.

The final major component of Ratzinger’s liturgical reform lies in releasing a wider permission for celebration of the pre-conciliar Missal (called in various circles the traditional Latin Mass, the 1962 Missal, the Tridentine Mass), an idea he advocated for as a cardinal and brought into the Church’s life as Pope through his motu proprio Summorum Pontificum in 2007. This more widespread usage, he believed, would offer two main benefits to the Church. First, it would serve as a bridge in two vital ways. It would help bring unity and reconciliation to the Church, serving as a way of reaching out to those groups that became disaffected with the Church over liturgical transitions or broke communion, such as in the case of the Society of St. Pius X. The use of the older form of the Mass, what Ratzinger calls “the Extraordinary Form,” would also bridge the gap between the pre-conciliar and post-conciliar Church: “There is no contradiction between the two editions of the Roman Missal. In the history of the liturgy there is growth and progress, but no rupture. What earlier generations held as sacred, remains sacred and great for us too, and it cannot be all of a sudden entirely forbidden or even considered harmful.”[6]

The second main benefit is that the two forms—the Ordinary and Extraordinary Forms—could “mutually enrich” and complement one another. The old missal could be used as a point of reference for celebrating the liturgy according to the new missal: “The celebration of the Mass according to the Missal of Paul VI will be able to demonstrate, more powerfully than has been the case hitherto, the sacrality which attracts many people to the former usage,” Ratzinger writes. “The most sure guarantee that the Missal of Paul VI can unite parish communities and be loved by them consists in its being celebrated with great reverence in harmony with the liturgical directives. This will bring out the spiritual richness and the theological depth of this Missal.”[7]

At the same time, Benedict believes that aspects of the new missal, which he called the Ordinary Form of the Roman rite, such as new Saints and new prefaces can and should be inserted into the old missal and that the genuine achievements in participation in the postconciliar era can influence the way the old rite is celebrated and entered into. Above all, Benedict here displays a preference for an authentic liturgical pluralism in the Church’s life, where numerous forms are able to coexist peacefully and bear witness to the undivided faith of the Church.[8]

Liturgical Renewal of Benedict XVI

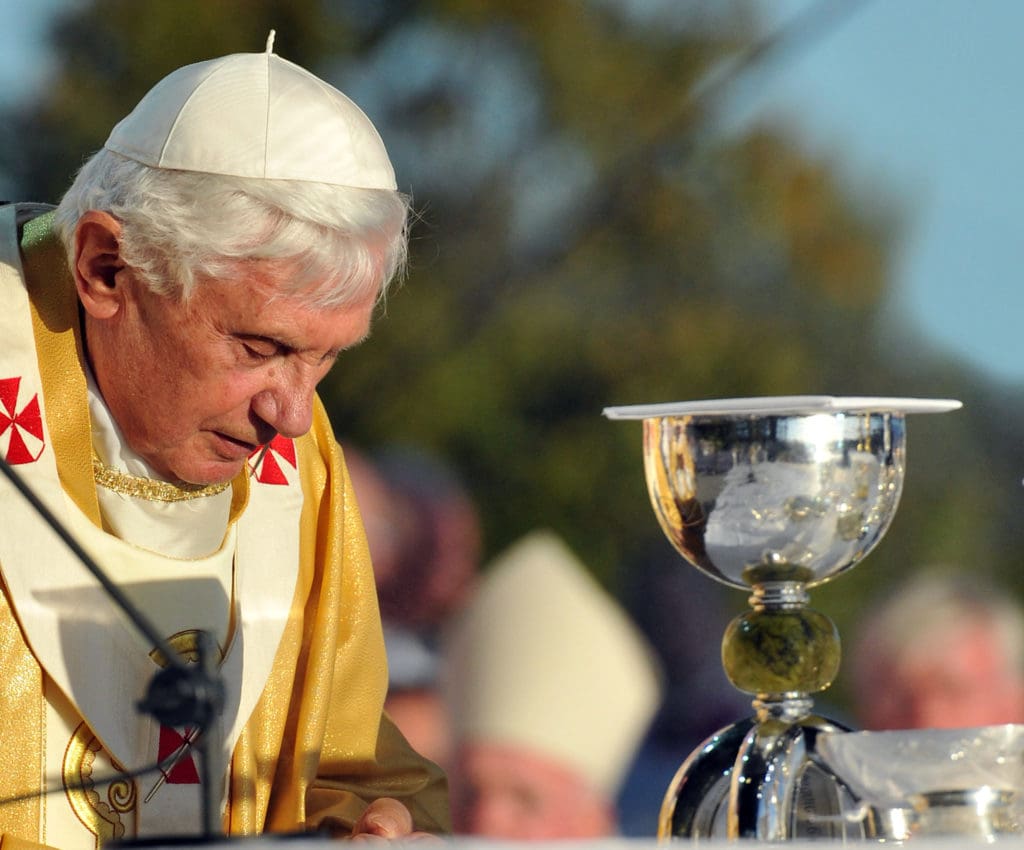

Instead of initiating major structural reforms to the liturgy as pope, Benedict focused on his role as a liturgical catechist and educator; in this role it was especially important that he led by personal example in his own celebrations of the liturgy. His teaching as pope highlights common themes throughout his career as a theologian and cardinal—the centrality of God in the liturgy and its nature as being first and foremost opus Dei, the work of God; the nature of the liturgy as given-not-made; the cosmic dimensions of the liturgy; the orientation of liturgical prayer; the importance of the gesture of kneeling and the adoration of the Eucharist; among others. Central features of Benedict’s liturgical teaching can be found in a clear and profound way in his post-synodal exhortation Sacramentum Caritatis (2005). Among the many rich aspects of Benedict’s liturgical teaching I wish to highlight two: his notion of the ars celebrandi and advocacy for the way of beauty.

Benedict describes the ars celebrandi as the “fruit of faithful adherence to liturgical norms in all their richness” and the foundation for authentic active participation: “The primary way to foster the participation of the People of God in the sacred rite is the proper celebration of the rite itself. The ars celebrandi is the best way to ensure their actuosa participatio. The eucharistic celebration is enhanced when priests and liturgical leaders are committed to making known the current liturgical texts and norms…. The ars celebrandi should foster a sense of the sacred and the use of outward signs which help to cultivate this sense, such as, for example, the harmony of the rite, the liturgical vestments, the furnishings and the sacred space.”[9]

For Benedict, it is not primarily a matter of changing the rites again (for this would in many ways repeat some of the errors of the last 50 years) but of changing ourselves and our own attitudes towards the liturgy.

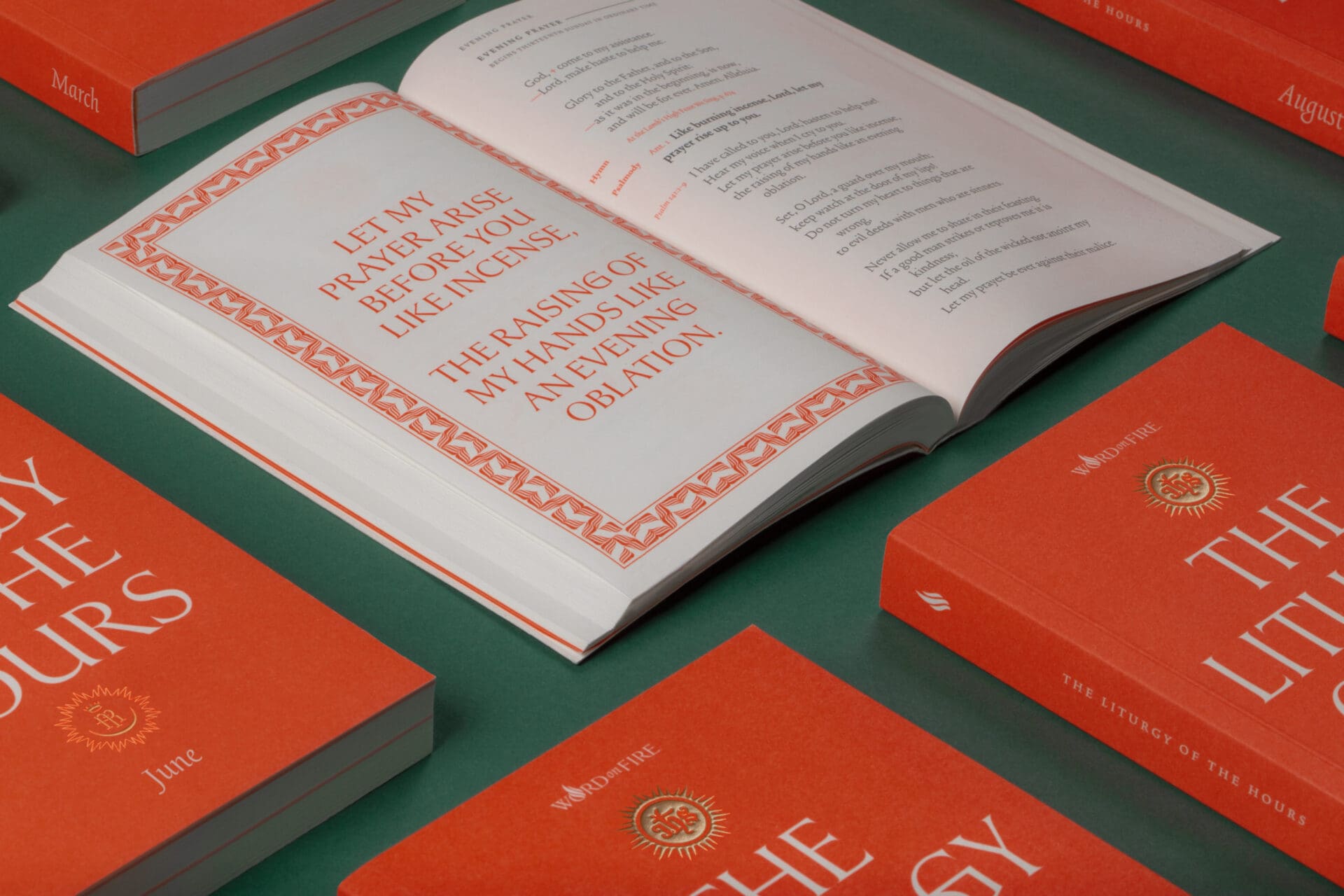

Closely related to this encouragement of ars celebrandi is his affirmation of beauty as a key to contemporary liturgical renewal: “[T]he liturgy is inherently linked to beauty: it is veritatis splendor…. [Because] in Jesus we contemplate beauty and splendor at their source, [the care for beauty in the liturgy] is no mere aestheticism, but the concrete way in which the truth of God’s love in Christ encounters us, attracts us and delights us.”[10]

“Everything should be marked by beauty,” Benedict reminds us as he encourages special respect and care in the construction of vestments, liturgical furnishings, sacred vessels, the altar, etc., “so that by their harmonious and orderly arrangement they will foster awe for the mystery of God, manifest the unity of faith, and strengthen devotion.”[11]

This concern for beauty was not just theoretical, a mere matter of nice words in an official Church document, but something visibly lived out in his own liturgical style. His ars celebrandi as pope served as an example for the entire Church. Pope Benedict was noted as a humble, restrained, and dignified celebrant of the liturgy, giving witness to his teaching that the liturgy should be centered on God, not the idiosyncrasies of the priest-celebrant. The papal liturgies under his master of ceremonies, Msgr. Guido Marini, were noted for their solemnity and beauty and displayed many aspects of Benedict’s liturgical teaching. Benedict occasionally celebrated Mass ad orientem publicly and used the altar cross arrangement he recommended in his The Spirit of the Liturgy, such that this practice has been called the “Benedictine arrangement.” This new arrangement places the crucifix at the center of the altar and three high candlesticks at each side with the body of Christ on the crucifix facing the celebrant as his point of reference. Benedict’s teaching on the importance of kneeling was given concrete expression in his decision in 2008 to introduce the practice of distributing communion to the faithful at a kneeler, preferably on the tongue, in papal masses. Benedict even visibly manifested his “hermeneutic of continuity” in his choice of liturgical vestments, using papal staffs and historical garments used by his papal predecessors as well as modern vestments, all in an attempt to model the “uninterrupted continuity” of the Church’s life.

But this is not to say that Benedict did not make any disciplinary attempts to correct certain erroneous practices. For example, in 2006 Pope Benedict called for the translation of pro multis as the more literal “for many” rather than “for all,” a move consonant with his desire for more faithful and literal translation from the Latin originals. In addition, Benedict also sought to correct liturgical abuses and what he considers inappropriate practices: rescinding the indult permission for extraordinary ministers of holy communion to purify sacred vessels after Mass, and restoring this action to the priest or deacon; removing Eucharistic prayers for children from the missal, which had “failed to adequately convey a sense of the sacred”; abandoning the use of the tetragrammaton (the Hebrew name of God, YHWH) in the liturgy, in light of “immemorial tradition”; and correcting some liturgical practices of the Neocatechumenal Way by insisting they return to the prescribed liturgical books without “omitting or adding anything.”[12]

Benedict’s Vision of Re-Catholicizing the Liturgy

More recently we have seen increased attacks on the authority of the Second Vatican Council and its liturgical reforms from a vocal minority of radical traditionalists, particularly online and on social media. This renders the balance, nuance, and pastoral sensitivity of Benedict’s approach very timely. While Benedict has expressed his critique of postconciliar developments in strong language, he nevertheless remained convinced of the many positive developments emerging from the Second Vatican Council and its liturgical reforms. In Sacramentum Caritatis he claims that “the difficulties and even the occasional abuses which were noted…cannot overshadow the benefits and the validity of the liturgical renewal, whose riches are yet to be fully explored.”[13] Overall, I would judge that Benedict’s liturgical reforms are not truly reforms in the strictest sense. They are concerned with how the liturgy is celebrated rather than mere superficial ritual changes or substantive structural alterations. For Benedict, it is not primarily a matter of changing the rites again (for this would in many ways repeat some of the errors of the last 50 years) but of changing ourselves and our own attitudes towards the liturgy. True active participation consists of an “awareness of the mystery being celebrated and its relationship to daily life.”[14] Even Benedict’s external reforms—such as celebrating ad orientum or with an altar cross, reception of communion kneeling, and more Latin and Gregorian chant—are compatible with and foreseen by the Missal of Paul VI.

Benedict himself desired that we see his own contributions less in terms of his concrete recommendations on external matters but as a retrieval of the spirit of the liturgy, and its central role in the life of the Church and, by extension, in our own daily walk with the Lord. Much of Benedict’s liturgical vision advances what liturgical scholar Msgr. M. Francis Mannion calls the “recatholicization” of the liturgy—a renewal of the “spiritual, mystical, and devotional dimensions of the revised rites” in order to vitally recreate the “ethos that has traditionally imbued Catholic liturgy at its best—an ethos of beauty, majesty, spiritual profundity, and solemnity.”[15]

In the closing words of his personal introduction to the volume on the liturgy in his Collected Works, Pope Benedict states that the essential purpose of his work on liturgy is “to go beyond the often petty questions about one form or another and to place the liturgy in its larger context…. I would be happy if the new edition of my liturgical writings could help others see the greater perspectives of our liturgy and put petty quarrels about external forms in their proper place.”[16] Let us rejoice in the wisdom of this profoundly liturgical pope by following his example and allowing the liturgy to transform and renew us today.

For the first part of this article, see Benedict XVI and the Reforms of the Second Vatican Council: Re-Catholicizing the Liturgy—Part I

Kevin D. Magas holds an MTS and PhD in theology from the University of Notre Dame. He currently serves as an assistant professor of dogmatic theology and director of intellectual formation for the Liturgical Institute at the University of St. Mary of the Lake/Mundelein Seminary. He lives in Mundelein, IL, with his wife and children.

Notes:

Joseph Ratzinger with Vittorio Messori, The Ratzinger Report. An Exclusive Interview on the State of the Church (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1985), 35. ↑

- Ibid., 37-38. ↑

Cf. Bilniewicz, Liturgical Vision of Benedict XVI, 107-149. ↑

Ratzinger, Spirit of the Liturgy, 8-9. ↑

Ratzinger, Salt of the Earth. Christianity and the Catholic Church at the End of the Millenium. An Interview with Peter Seewald. (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1997), 177. ↑

Pope Benedict XVI, Letter to Bishops accompanying Summorum Pontificum (Juy 7, 2007). ↑

Ibid. ↑

This article was written in advance of Pope Francis’ Motu Proprio Traditionis Custodes, which substantially reverses the liturgical legislation on the wider liberalization of the 1962 Missal found in Summorum Pontificum. While ensuing discussions of this document have left unanswered questions and often generate more heat than light, a helpful and irenic analysis contextualizing this development can be found in the two-part article series by William Johnston: “Traditionis Custodes: How Did We Get Here?” (Church Life Journal, Oct. 1, 2021); “Traditionis Custodes Challenges Everyone” (Church Life Journal, Nov. 5, 2021). We should also attend to the points of continuity between Traditionis Custodes and Summorum Pontificum. In the letter accompanying Traditionis Custodes, Francis cites Summorum Pontificum when he asserts that he is “saddened by abuses in the celebration of the liturgy on all sides. In common with Benedict XVI, I deplore the fact that ‘in many places the prescriptions of the new Missal are not observed in celebration, but indeed come to be interpreted as an authorization for or even a requirement of creativity, which leads to almost unbearable distortions.’” See https://adoremus.org/2021/07/accompanying-letter-to-traditionis-custodes/ ↑

Pope Benedict XVI, post-synodal Exhortation Sacramentum Caritatis 38; 40. ↑

- Ibid., 35. ↑

- Ibid., 110. ↑

See Bilniewicz, The Liturgical Vision of Pope Benedict XVI, 195-203. ↑

Sacramentum Caritatis, 4. ↑

Ibid., 52. ↑

M. Francis Mannion, “The Catholicity of the Liturgy: Shaping a New Agenda,” in Masterworks of God: Essays in Liturgical Theory and Practice (Chicago/Mundelein, IL: Hillenbrand Books, 2004), 216-217. ↑

Pope Benedict XVI, Collected Works, xvii. ↑