The debate surrounding preconciliar and postconciliar liturgical books did not begin with the Second Vatican Council, but with the Council of Trent. In Pope Pius V’s 1570 promulgation of the Tidentine Missal, Quo Primum, the Holy Father banned any Missals younger than 200 years. Those areas where rites and customs had existed for longer than 200 years could continue to celebrate the Mass according to their tradition, although they could also “celebrate Mass according to its [new] rite, provided they have the consent of their bishop” if they found it “more agreeable.”

Some did not find it more agreeable.

French Catholics, for example, feared that Rome and its Rite would check their Gallican independence—and their Gallican liturgical books. As members of the Sorbonne said at the time about the post-Trent breviary (promulgated 1568): “The adoption of the Roman breviary would diminish the authority of bishops and of dioceses…. The bishops have regulatory and police powers in their diocese, just as the bishop of Rome in his; this great good would be lost by the change in question. This enterprise would be against the liberty of the Gallican church, which, if she submitted on so capital a point, would remain subject to [Rome] in all the rest.”

The Church in France’s independent streak would continue for centuries. But after the French Revolution and its aftermath, French Catholics began to look once again over-the-mountains (thus, the rise of ultramontanism) to Rome and her rites. And as it was bishops and scholars who once rejected the Roman books, it was bishops and scholars who would now seek a reunion. The Bishop of Langres, for example, had come to see firsthand the problems of having five different Gallican missals at use in his one diocese. (And some today think two forms is problematic!) But the main energy in the 19th-century ultramontanist liturgical movement was Dom Prosper Guéranger.

Guéranger was born in 1805—a tumultuous time in France. The French Revolution had ended in 1799; Napoleon had been crowned Emperor in 1804; Pius VII had been kidnapped and brought to France by Napoleon in 1812. Despite (or because of) these times, Guéranger discerned a vocation to the priesthood and was ordained to the Diocese of Le Mans in 1827. An early assignment found him serving a group of religious from Rome where he was introduced firsthand to the Roman tradition, providing an enlightening contrast to his native Gallican traditions, which had existed from before the Council of Trent. A great deal of his subsequent life was spent working for ritual reunion with Rome. After reopening the Priory of Solesmes in 1833 and reestablishing a Benedictine order there, he worked for the restoration and singing of Gregorian Chant; at this time, he also researched and wrote about the Roman liturgy (Thérèse of Lisieux recounts in her autobiography how her saintly parents would read to her and her siblings from Guéranger’s The Liturgical Year).

Ecclesial and liturgical unity did not begin with Guéranger, but he does illustrate this most fundamental of principles in a heroic way (the cause for Guéranger’s beatification began in 2005). Jesus’ high priestly prayer from the Last Supper expresses the desire “that those who will believe in me…may all be one, as you, Father, are in me and I in you, that they also may be in us” (John 17:20-21). You, me, Pope Francis, Prosper Guéranger, Christ—although individuals, are called to unity in God. St. Paul speaks to a similar diversity-in-unity when writing of the Church: “As a body is one though it has many parts, and all the parts of the body, though many, are one body, so also Christ” (1 Corinthians 12:12). Accordingly, despite accidental differences of time and culture, Catholics profess belief in “one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church.”

In our own day, too, the Church continues to balance legitimate diversity within substantial unity. Among the Second Vatican Council’s principal goals were “to adapt more suitably to the needs of our own times those institutions which are subject to change [and] to foster whatever can promote union among all who believe in Christ” (Sacrosanctum Concilium, 1). Even among missales and rituales—and now I speak of Vatican II’s pre- and postconciliar books—the sought-after balance between unity and diversity is a primary concern. Both Pope Benedict and Pope Francis made the decisions they did motivated by unity: Benedict says, “It is a matter of coming to an interior reconciliation in the heart of the Church” (Letter accompanying Summorum Pontificum), while Pope Francis says he is motivated “In order to promote the concord and unity of the Church” (Traditiones Custodes). However the objective is reached—and while methods and opinions differ—the goal of achieving unity-among-diversity remains.

Adoremus: Society for the Renewal of the Sacred Liturgy works for this same goal. A new dimension to our work begins with this May 2022 issue: Adoremus has officially begun printing and distribution from Sydney, Australia, to all present and future readers in Oceania.

Adoremus, thankfully, has had readers in Australia and New Zealand since its start in 1995. But as of now—thanks to current readers in Perth, to Parousia Media in Sydney, and to donors across Australia—the Bulletin will come to local readers from within Australia itself. A component part of this promotion is the opportunity for all in Oceania who desire it to receive the Bulletin—in print and/or electronically—free of charge between now and March 2023. Simply email orders@parousiamedia.com or visit www.parousiamedia.com/adoremus-bulletin/. A final element celebrating our Australia-New Zealand launch features authors from Australia in each of the upcoming issues—which we in North America will be grateful to read, too! In the present issue, see the entry on the nature of mystagogical catechesis by Dr. Gerard O’Shea, a professor of religious education at the University of Notre Dame, Australia, and at Campion College, Sydney. We are grateful to all of our new friends, readers, and collaborators Down Under for making this new endeavor happen.

I am no modern-day Guéranger, and the geographic ocean between the United States and Australia is not the same as the political mountains separating 19th century France from Rome. Still, all involved in today’s endeavor will continue to implement, celebrate, and love the Roman Rite liturgy in the years ahead. And, if God so blesses our work, we “may be brought to perfection as one” (John 17:23).

Christopher Carstens is director of the Office for Sacred Worship in the Diocese of La Crosse, Wisconsin; a visiting faculty member at the Liturgical Institute at the University of St. Mary of the Lake in Mundelein, Illinois; editor of the Adoremus Bulletin; and one of the voices on The Liturgy Guys podcast. He is author of A Devotional Journey into the Mass and A Devotional Journey into the Easter Mystery (Sophia), as well as Principles of Sacred Liturgy: Forming a Sacramental Vision (Hillenbrand Books). He lives in Soldiers Grove, Wisconsin, with his wife and eight children.

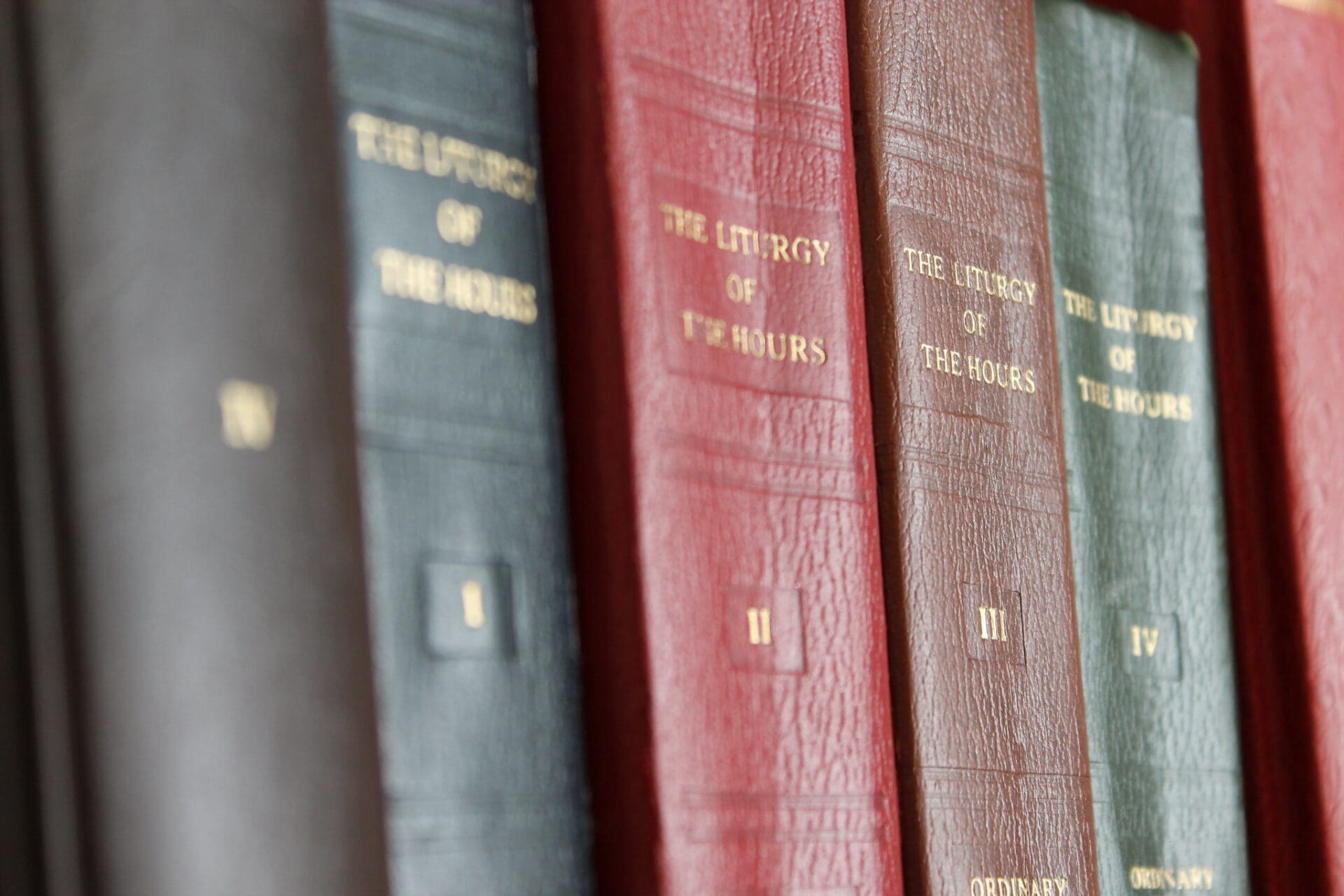

Image Source: AB/Wikimedia