Unity and Diversity in the Development of the Missal

The later Middle Ages witnessed a liturgical standardization according to the model of the Roman curia, which increasingly shaped local diocesan uses. Despite such tendencies towards unification, variations in the missals of dioceses and religious orders remained and were noteworthy in certain respects: in the formal presentation of liturgical formularies (such as the names for of the Mass propers); in the prayers, readings, and chants assigned to feasts; in the sanctoral cycle of the calendar; and in the structure and sequence of sections within the missal. Even where the Order of Mass essentially followed the use of the Roman curia (“Ordo missalis secundum consuetudinem Romane curie”), there were differences in the texts and rubrics of the introductory and the concluding rites. Likewise, the ritual shape and the prayers of the offertory were by no means uniform. Liturgical diversification increased with the addition of new saints’ feasts, the proliferation of prefaces, tropes and sequences (of uneven quality), and the multiplication of votive Masses.

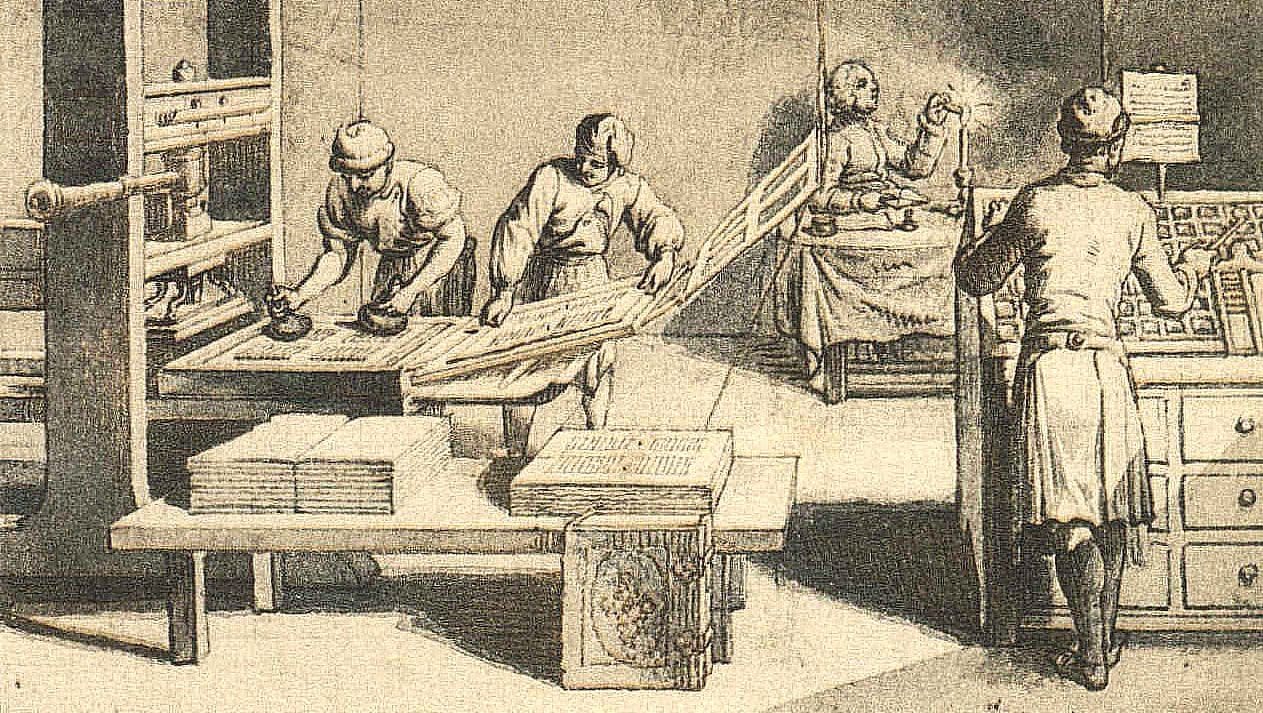

In general during this time, diocesan bishops did not have effective control over the making of liturgical books in their territories. Before the invention of printing, manuscripts for liturgical use were usually copied at the initiative of local churches and their clergy, who would engage scribes for this particular purpose.[1] Local nobility or other patrons would often donate missals and be involved in their production. Episcopal leadership was mostly reactive, and its limits are illustrated by the largely unsuccessful efforts of Nicholas of Cusa, who as bishop of Brixen (modern day Italy) tried to enforce the correction of missals in use according to approved normative manuscripts at two diocesan synods in 1453 and 1455.[2] The new, fast-growing and largely unregulated printing industry dramatically simplified the production of liturgical books and gave printers an important role in this process. Printers would confidently supply their editions with Mass formularies that corresponded to devotions popular at the time, perhaps with the collaboration and the advice of local clergy.

Codification of Ritual

The move of the papacy to Avignon in 1309 brought the cycle of stational liturgies in Rome to a definite halt. In Avignon, papal liturgical celebrations were also held in the setting of the palace. Even after the return of the pope to Rome in 1378 and the end of the Western Schism in 1417, the intimate link of the papal liturgy with the urban churches was never resumed.[3] The Vatican palace became the pope’s preferred residence, and major liturgical celebrations were held in its “great chapel” (capella magna), known as the Sistine Chapel since its rebuilding under Pope Sixtus IV (r. 1471-1484).

In the course of the 15th century, the papacy regained momentum, and its liturgical celebrations once again began to be imitated by bishops throughout the Latin Church. The papal masters of ceremonies Agostino Patrizi Piccolomini (d. 1495), Johann Burchard (d. 1506) and Paride Grassi (also referred to by his Latinized name Paris de Grassis (d. 1528)), were responsible for organizing both liturgy and court ceremonial, and left extensive written records of their work (prescriptive ceremonial books, descriptive diaries, and treatises).

These masters of ceremonies were working in a tradition going back to the Ordines Romani of the early medieval period. From the late 13th century onwards, ceremonial instructions became more systematic and specific, and they had considerable impact beyond their immediate purpose throughout the Latin Church.[4] The work that was to become decisive for the further development of the ritual shape of the Roman Mass was the Ordo Missae of Johann Burchard. The first edition of 1496 is presented as an “Order to be observed by a priest in the celebration of Mass without chant and without ministers according to the rite of the holy Roman church,” which is compiled for the purpose of “the instruction of newly ordained priests.”[5] The scope of the second edition, printed in 1502 with a letter of approval from Pope Alexander VI, is much broader than its predecessor: Burchard insists that its ceremonial instructions also apply to cardinals and prelates, including the Supreme Pontiff, when they celebrate Mass not pontifically but in private.[6]

The papal master of ceremonies thoroughly reworked his earlier ordo for the new edition, which offers much more detailed and comprehensive rubrical instructions. At this point, the ritual performance of gestures and movements became precisely regulated and meticulously explained. By contrast, the Ordinarium Missae (named after its incipit “Paratus sacerdos”), which was integrated into the Roman Missal and contained the recurring parts of the rite, was largely limited to prayer texts and only had room for very few rubrics. Thus the ordo of 1502 can be best understood in continuity with the 13th-century ordinal Indutus planeta. Burchard offers important specifications at three stages of the rite: First, in the introductory rites, Psalm 42 (Iudica me) is recited at the foot of the altar (which was the Roman practice at least since Indutus planeta), rather than in the sacristy or in procession to the sanctuary, as was common in diocesan uses. Second, while the offertory rite is fixed in its curial form, the 1502 ordo (but not the earlier edition) includes an offertory procession, which still had some currency at the time. Third, in the concluding rites the final blessing follows after the prayer Placeat tibi sancta Trinitas (“May it please you, O holy Trinity…,” which precedes the kissing of the altar), not vice versa, as in some diocesan uses and in early printed Roman Missals. The Last Gospel (John 1:1-14), which was not yet in general use and is not included in early printed Roman Missals, is to be read at the altar rather than said in a low voice from memory as the celebrant returns to the sacristy (as was the practice in the Roman pontifical high Mass and in some diocesan uses). The rationale for this particular change may have been to focus on the meaning of the sacred text, and to avoid a perfunctory recitation.

The most significant innovation in Burchard’s ordo concerns the reverential gesture for the consecrated Eucharist: when the celebrant has pronounced the dominical words over the bread, he is instructed to genuflect as a sign of adoration (“genuflexus eam adorat”). Then he elevates the consecrated host and after having placed it on the corporal again he genuflects a second time. In the same manner, the consecration of the chalice is followed by a genuflection before and after the elevation. The genuflection replaces the “medium bow” that is indicated in Indutus planeta for the adoration of the body of the Lord. Until the later Middle Ages, bowing towards the consecrated species remained the priest’s liturgical gesture of adoration, while kneeling in the presence of the sacrament was a characteristic expression of lay piety. The new practice was gaining currency in the late 15th and early 16th century. Burchard’s ordo of 1502 systematically stipulates genuflections, not only for the double consecration of bread and wine but also in subsequent moments of the rite when a sign of reverence to the body and blood of Christ is called for (when the priest uncovers or covers the chalice with the pall, and when he takes the consecrated host).

Conclusion

At the dawn of the early modern period, while a variety of diocesan and religious uses persisted, the Ordo Missae after the model of the Roman curia had been widely adopted throughout the Western Church. The tendency towards codification of ritual culminated in Johann Burchard’s detailed ordo of 1502, which became influential in the period leading up to the Council of Trent. In the next instalment I will look at the shape of the “Tridentine Mass.”

For previous instalments of Father Lang’s Short History of the Roman Rite of Mass series, see:

- Part I: Introduction: The Last Supper—The First Eucharist

- Part II: Questions in the Quest for the Origins of the Eucharist

- Part III: The Third Century between Peaceful Growth and Persecution

- Part IV: Early Eucharistic Prayers: Oral Improvisation and Sacred Language

- Part V: After the Peace of the Church: Liturgy in a Christian Empire

- Part VI: The Formative Period of Latin Liturgy

- Part VII: Papal Stational Liturgy

- Part VIII: The Codification of Liturgical Books

- Part IX: The Frankish Adoption and Adaptation of the Roman Rite

- Part X: Monastic Life and Imperial Patronage

- Part XI: Reform Papacy and Liturgical Unification

- Part XII: The Impact of the Franciscans on the Roman Mass

- Part XIII: Eucharistic Devotion of the High Middle Ages

- Part XIV: The Later Middle Ages: All Decay and Decline?

Father Uwe Michael Lang, a native of Nuremberg, Germany, is a priest of the Oratory of St. Philip Neri in London. He holds a doctorate in theology from the University of Oxford, and teaches Church history at Mater Ecclesiae College, St. Mary’s University, Twickenham, and Allen Hall Seminary, London. He is an associate staff member at the Maryvale Institute, Birmingham, and on the Visiting Faculty of the Liturgical Institute in Mundelein, IL. He is a Corresponding Member of the Neuer Schülerkreis Joseph Ratzinger / Papst Benedikt XVI, a Member of the Council of the Henry Bradshaw Society, a Board Member of the Society for Catholic Liturgy, and Editor of Antiphon: A Journal for Liturgical Renewal.

Notes:

Natalia Nowakowska, “From Strassburg to Trent: Bishops, Printing and Liturgical Reform in the Fifteenth Century”, in Past & Present, no. 213 (November 2011), 3-39, at 24, points to the evidence provided by contracts from fifteenth-century Poland and England. ↑

See Hubert Jedin, “Das Konzil von Trient und die Reform des Römischen Meßbuches”, in Liturgisches Leben 6 (1939), 30-66, at 40-41. ↑

See John F. Romano, “Innocent II and the Liturgy”, in Pope Innocent II (1130-43): The World vs the City, ed. John Doran and Damian J. Smith, Church, Faith and Culture in the Medieval West (Abingdon – New York: Routledge, 2016), 326-351, at 344-345. ↑

The papal ceremonials have been edited by Marc Dykmans, S.J., Le cérémonial papal de la fin du Moyen-Âge à la Renaissance, 4 vol., Bibliothèque de l’Institut Historique Belge de Rome 24-27 (Brussels – Rome: Institut Historique Belge de Rome, 1977-1985). ↑

Johann Burchard, Ordo missae secundum consuetudinem Romanae ecclesiae (Rome: Andreas Fritag and Johann Besicken, 1496) (ISTC ib01284400). The 1498 reprint has been digitised by the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana and is accessible at https://digi.vatlib.it/view/Inc.IV.528.. ↑

Johann Burchard, Ordo missae (Rome: Johannes Besicken, 1502); cited after Tracts on the Mass, ed. John Wickham Legg, Henry Bradshaw Society 27 (London: Harrison, 1904), 126. ↑

Image Source: AB/Wikimedia