An interview with Graham Crawley, member of Floriani, reveals the importance of Gregorian chant for the liturgy—and for the soul.

Floriani is a men’s vocal ensemble from Phoenix, AZ, dedicated to serving the Church and saving the culture through the beauty of sacred music. The group first formed in 2013, but officially took for themselves then name Floriani in 2018 before a pilgrimage they took to Rome. Floriani’s beginnings can be traced back to its origin as a “sort of barbershop choir,” but quickly sacred music (and chant, in particular) stole their hearts. They began to sing for weekend Masses, and always heard positive feedback. Many people even expressed that they had never heard such music at Mass before—and wanted more of it. While most members of the group never thought it would be possible to make this a full-time mission, last year they were able to achieve this.

When they were still students at Thomas Aquinas College in Santa Paula, CA, there were around 15 men in the group. Now Floriani consists of four men, but as they continue to fundraise, they hope to grow their numbers. The four current members graduated from Thomas Aquinas College between 2014 and 2020.

The group’s output and educational efforts are remarkable. Each member, and the group corporately, works tirelessly to revive Catholic sacred music in churches around the nation, and thus to open hearts to the Truth through beauty.

Floriani’s life so far has been marked with distinction. On the aforementioned pilgrimage to Rome, they sang for the High Mass on Pentecost, which was celebrated by Cardinal Raymond Burke. Subsequently, they were invited to sing in St. Peter’s Basilica for one of the Sunday Masses at the altar of the Chair of St. Peter. Since moving to Phoenix, they have sung for several Masses for their ordinary, Bishop Thomas Olmsted, plus a Mass celebrated by Cardinal George Pell in a private diocese chapel.

Special contributor for Adoremus, Paul Senz, spoke with Floriani member Graham Crawley about his experiences with Floriani, why sacred music is more important now than ever, and how sacred music will help change the liturgical landscape in the Church. Crawley is a native of Phoenix, and a member of Floriani since his days at Thomas Aquinas College.

Tell me about Floriani. How and why did it start?

The group was founded by Giorgio Navarini at Thomas Aquinas College (TAC) as a sort of barbershop choir. The group was made up of male students who loved to sing and would sing everything from Billy Joel to Renaissance-era polyphonic composer Tomas de Victoria. The group would be asked to sing for Masses in the Ventura, CA, area, near where TAC is located, and so began delving deeper into chant and other forms of sacred music.

We found that everywhere we went, people’s response to us was overwhelmingly positive. Without fail, we would have people come up to us after Mass saying they wanted more of this music, and how it was so beautiful, etc. Many people had never heard anything like it, and some loved it because it reminded them of the chants they heard when they were children growing up in the pre-Vatican II era. Eventually, 15 of us raised money to go on pilgrimage to Rome to sing in as many churches as possible, and we took the name Floriani after Giorgio’s confirmation saint, St. Florian. We sang in each of the four Major Papal Basilicas, including St. Peter’s, where we sang for a Sunday Mass.

In short, we all fell in love with the great musical tradition of the Church and saw a deep desire for its return amongst people of all ages. We would get these requests from people to return to their church to sing, or to do a chant workshop, but since we were in school, our time was limited. A few of us had this dream to sing chant full time, and a few years after we all graduated, things lined up and we made that vision a reality. We quit our jobs and moved to Phoenix to begin the mission full time.

Why is a “revival” of Catholic sacred music necessary?

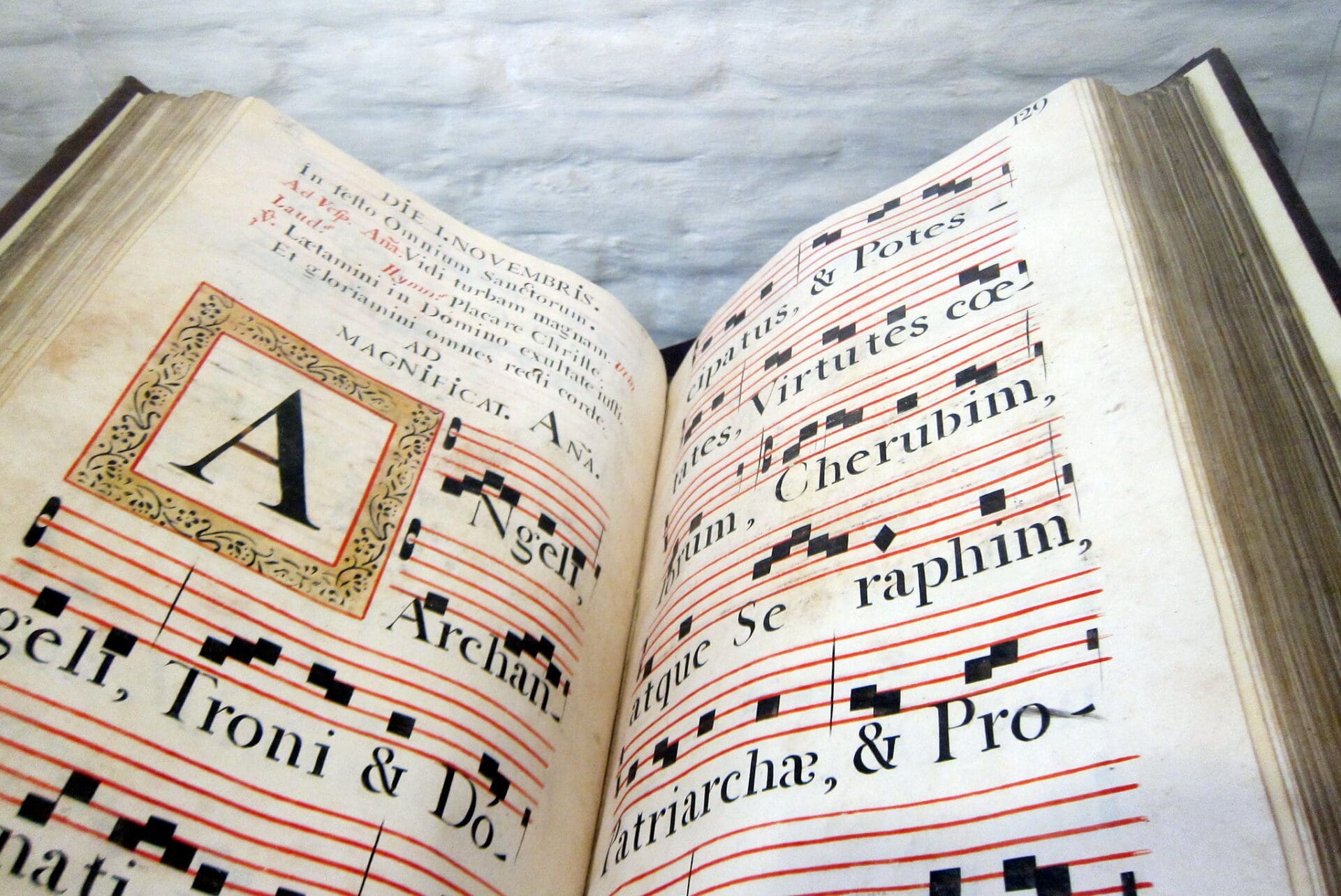

The simple answer: the tradition of Catholic sacred music (especially Gregorian chant) is beautiful and holy, and Vatican II calls for its presence in the liturgy. I would say that, in all the world, there is no tradition of sacred music as vast and diverse as the Church’s. And that’s just it. It is our inheritance as Catholics, and, for the most part, it’s not sung these days in the liturgy at all. Many Catholics hardly know it exists. Yet even the secular world recognizes its beauty, albeit removed from the spiritual dimension that inspired it. Musicians and aficionados around the world still celebrate it as timeless and precious art—this should at least suggest to us its aesthetic value. Within the liturgy, the sacramental power of the music brings with it ages of prayerful contemplation of the scripture and intimates the solemn reality of what is happening on the altar. Its melodies change with the liturgical seasons, and thereby guide our hearts and minds along the story of salvation, from the Incarnation to the Passion to the Resurrection, uniting us in our worship to all Catholics, those living today and those who came before us.

Since the Second Vatican Council, the Church has been in what seems to me to be a sort of identity crisis. The implementation of the Council’s decisions resulted in a wide-scale upheaval, which, in many cases, runs contrary to the Council documents’ stated intention. For instance, the use of Latin in the liturgy was meant to be preserved, yet in most places it was completely scrapped. Another (and more apropos) example is Vatican II’s stance on the tradition of sacred music, especially as regards Gregorian chant. The conciliar document on the liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, calls the musical tradition of the Church “a treasure of inestimable value, greater even than that of any other art,” and that Gregorian chant ought to “be given pride of place in liturgical services.” More than superseded, the chant has been all but forgotten in most parishes.

Lastly, from our experience, there is a growing number of people who thirst for this kind of music and don’t know how to perform it or where to find it. There is certainly a movement towards a more traditional, reverent liturgy, and perhaps this is due to the increasing lack of beauty and sacredness in the world. As modernity seeks to clear the slate for a sterile and manufactured world, it makes sense that more and more people want to return to the roots. It’s in our nature. We long for true expressions of culture, which are beautiful insofar as they reach for Truth. The more beautiful these expressions are, the more they will answer to our innate longing for communion with the Source of Beauty. Truly sacred music does this in a way no other art can, and the liturgy is more deserving of this ornamentation than anything else.

Catholics looking to revive art or liturgy or architecture are often accused of trying to “turn back the clock” or of having rose-tinted glasses about the pre-conciliar Church. How would you respond to that, in the context of Floriani?

While it may be true that the pre-conciliar Church was in great need of change, the implementation of the Council seems largely to have thrown the baby out with the bath water. Is the answer to concerns over the pre-conciliar liturgy to cast aside 2,000 years of liturgical development, passed on and refined by the saints through the ages? Was the tradition of chanting the scriptures in Mass the cause of the problems? Did the beautiful architecture and elaborate stained glass scare people off? If there was liturgical abuse, then obviously that ought to have been addressed. But to flippantly cast aside a tradition rooted in the days of the Apostles is presumptuous, to say the least, and again, according to the Council itself, this was not the stated intention. And further, was the abuse addressed? My point is not at all to deride the Novus Ordo, but simply to point out that though there was abuse before, there is also plenty of it today.

This debate around revival of tradition is not merely about old art vs. new art, or old music vs. new music, or an old, idealized Mass vs. a new, more accessible Mass. The question at stake is fundamental: What is the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass? Is it a community worship session? Or is it a sacrifice, in the Old Testament sense of the word? If the former, then whatever the community’s preference for music, whatever helps them pray, should be the focus of musical choice. But if the Mass is the re-presentation of Calvary, where Christ offers himself to the Father for the sins of the world, then the liturgical act is something beyond a community prayer. Rather than being ordered outwards towards us, it should be ordered upwards to God, and, insofar as the priest is acting in persona Christi, by God.

When we participate in the Holy Mass, we are participating in the redemptive act of the Crucifixion. We are entering a sacramental anticipation of the New Jerusalem. All of our aesthetic choice ought to reflect this reality, such that it would be impossible to mistake it for something other than sacred and otherworldly. Thus, the liturgy is not so much about personal preference as it is about offering God our first fruits, fruits anointed specifically for this purpose. It seems to me we would be remiss to ignore the traditions passed down, which were themselves honed and refined by Mother Church, who was appointed by Christ to safeguard all that is Good, True, and Beautiful. It’s not about returning to the old way: it’s about resurrecting what was worthy then and incorporating it into our current expression.

Is sacred music necessarily tied to the liturgy? Or, alternatively, does sacred music outside the liturgy have some sort of intrinsic liturgical foundation?

Taking plain chant as the gold standard of sacred music, you see that the intrinsic connection of sacred music to the liturgy is clearly the case. The vast majority of chant is scripture put to song. It is unique, because the words were not fit into melody, but rather, the melody arose from the words. That is to say, the melody serves the text, and not vice versa. And just as all of scripture is ordered to Christ as the focal point, so too is the liturgy. I suppose, in a manner of speaking, the Holy Mass is the sacramental reenactment of the culmination of all of scripture, so the two are intrinsically connected. Bishop Thomas Olmsted writes, “Religious music comes from human hearts yearning for God; liturgical music comes from Christ’s heart, the heart of the Church, longing for us.” This is essential to sacred music: that it is beautiful and holy (in an objective sense), and insofar as it is these things, it is incarnate of Christ himself.

What are some of the ways Floriani is “getting out there” to Catholics who may not have heard of Floriani?

We are currently based at St. Anne’s in Gilbert, AZ, singing for a few Masses every Sunday and raising a few choirs. In our spare time we travel to parishes around Phoenix and elsewhere to sing for Masses, perform concerts, and run workshops at any parish or school that will have us. It is our mission to introduce people and educate them in the practice of sacred music, so our goal is to do this for as many people as possible. We put out a podcast every week called Chant School (www.floriani.org/podcast) which teaches people how to chant through hearing and repetition, covering everything from the simple hymns like Ave Maria and Jesu Dulcis Memoria, to the more complex Propers sung at Mass. We are also working on our online presence (Instagram, music streaming sites like Spotify/Apple Music, and YouTube), recording CDs, and composing original music to be used in the liturgy.

Tell me about the Chant School podcast. How did that start, and what are your plans for it?

The Chant School podcast came about as we were trying to find a way to teach people the chant online. Chant was passed on aurally for hundreds of years, so the method is by no means a novel one, though we hadn’t seen any other current sacred music resources doing it this way. The plan is to put out all the Ordinaries, Propers, antiphons and hymns of the Church, week by week. It’s a big task, but it’s been a great way to get to know the chants well. Also, we are planning to expand to do interviews and discussion regarding the subject of chant and sacred music. So, stay tuned! Much more to come.

What can readers do to support Floriani?

First and foremost, please pray for us. Second, we do this full time and rely completely on the patronage of people who support our cause. Currently, we are searching for sustaining financial partners who share our fervor for this important mission. Visit our website, www.floriani.org, to learn more or to donate. Also, subscribe to our YouTube channel, follow us on Instagram (@florianisacredmusic), and tune in to the Chant School podcast! If you want to bring us to your parish or know anyone else who would be interested in this, reach out to us at [email protected].

Paul Senz has an undergraduate degree from the University of Portland, OR, in music and theology and earned a Master of Arts in Pastoral Ministry from the same university. He has contributed to Catholic World Report, Catholics Answers Magazine, Our Sunday Visitor, The Priest Magazine, National Catholic Register, Catholic Herald, and other outlets, and is the author of Fatima: 100 Questions and Answers about the Marian Apparitions (Ignatius Press). Paul lives in Elk City, OK, with his wife and their four children.

Image Source: AB/Wally Gobetz on Flickr