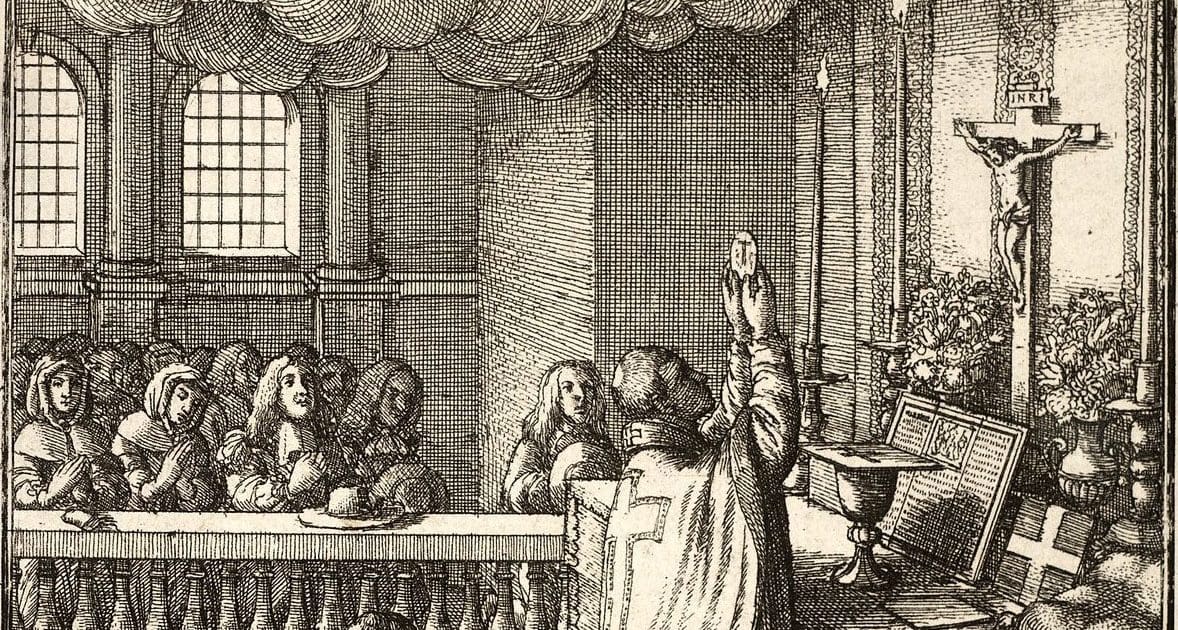

The interplay of doctrinal clarification and popular devotion in the medieval period led to a heightened sense of the real presence of Christ in the liturgy of the Mass.[1] Kneeling during the Eucharistic prayer had become increasingly common among the laity since the ninth century. Starting from France, possibly as a reaction to the Albigensian denial of incarnational and sacramental reality,[2] priests would elevate the consecrated host for the adoration of the faithful, after pronouncing the words of Christ over it. The practice was confirmed by the bishop of Paris, Odo of Sully (d. 1208), and in the course of the 13th century, the elevation of the consecrated chalice was likewise introduced. The elevations could be accompanied by a special candle, by the ringing of a handbell, or even by the tolling of the church bells. St. Francis of Assisi promoted these new forms of Eucharistic devotion enthusiastically and strongly encouraged the lay faithful to kneel at the elevation of the consecrated species at Mass and when the Blessed Sacrament was carried in procession.[3]

Reception of Communion

Fourth- and fifth-century sources indicate that, by that period, the reception of communion by the laity had already become less frequent than in former times. Some Carolingian bishops encouraged the faithful to receive the sacrament more often, but these efforts had little apparent success, and ecclesiastical legislation largely followed the pattern set by the council of Agde in the south of France, held in 506, which obliged general communion three times a year, at Christmas, Easter and Pentecost.[4] The people’s vivid faith in Christ’s presence in the Eucharistic species and the sense of their own sinfulness made the reception of communion a rare occasion. The Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 even saw the need to legislate that the faithful had to receive the sacrament at least once a year in the Easter season (“in pascha”).[5] By that time, the chalice was no longer given to the laity in most churches, and since the eighth or ninth century a thin wafer of unleavened bread, made of water and wheat, had become the norm for use at Mass.[6]

From the 11th century, the use of hosts that were consecrated in another Mass began to spread. Until then, this practice was limited to the Mass of the Presanctified on Good Friday, when the sacrament that had been confected on Maundy Thursday was distributed. If at a Mass consecrated hosts were left over, they were ordinarily consumed by the priest. The administration of Holy Communion outside Mass (apart from communion for the sick or dying) is first attested in the 12th century. Until the 16th century, this practice seemed to happen only at Easter and other major feasts when there were many communicants, and the sacrament was distributed right after Mass so as to maintain a connection with the offering of the sacrifice.[7]

Reservation of the Eucharist

The reservation of the Eucharist to make it available to the sick and the dying has its roots in Christian antiquity. The conditorium mentioned in Ordo Romanus I[8] probably means a cupboard or chest kept in the sacristy (a custom maintained in northern Italy, including Milan, until the 16th century). In the early medieval period (c.600-1000), it was established to keep the consecrated hosts in churches, to protect them from profanation and to prevent superstitious practices, and various places and forms of reservation are attested. The ordinal of the Dominican missal of 1256 and the ceremonial ordinationes of the Augustinian friars of 1290 stipulate that the sacrament is to be reserved on the high altar (altare maius). The common source for the practice of these orders (there is apparently no similarly precise indication in contemporary Franciscan documents) may well be the papal chapel, where the sacrament was customarily (though with exceptions) kept at the high altar.[9]

From the late 13th century, the word tabernaculum (“tabernacle” or “tent”) was employed to indicate the receptacle for the sacrament of the altar. The biblical associations of the term are significant, since the Tent of Meeting was God’s presence among the people of Israel in the desert. The prologue of St. John’s Gospel states that the divine Word “was made flesh and dwelt [literally, “pitched his tent”] among us” (John 1:14). In the Apocalypse the heavenly Jerusalem is evoked with the words: “Behold the dwelling of God is with men,” which reads in the Vulgate: “Ecce tabernaculum Dei cum hominibus” (Revelation 21:3).

Corpus Christi

Medieval veneration of the Eucharist reached its climax with the introduction of the feast of Corpus Christi and the forms of popular devotion associated with it: procession, exposition, and benediction of the Blessed Sacrament. The proximate origins of Corpus Christi are connected with the visions of St. Juliana (d. 1258), a lay sister serving in a leprosarium (leper house) connected with the Premonstratensian (i.e. Norbertine) house of Mont-Cornillon near Liège.[10] The idea of a new liturgical feast dedicated to the Eucharist resonated widely, was promoted especially by the Dominicans, and its observance spread through the Low Countries and Germany. Jacques Pantaleon, Archdeacon of Campines in the Diocese of Liège and a great supporter of Juliana, became pope as Urban IV (r. 1261-1264), and in his 1264 bull Transiturus decreed the celebration of Corpus Christi for the whole Church on the Thursday after Trinity Sunday. The date was chosen to connect the new feast with Maundy Thursday, when the institution of the Eucharist is commemorated, and it was in fact the first available Thursday after the conclusion of the Easter season. Recent research has confirmed the traditional ascription of the Mass and Office for Corpus Christi to St. Thomas Aquinas.[11]

Urban IV died shortly after Transiturus and his immediate successors seemed to have little interest in the new feast; nonetheless, its celebration spread throughout the Western Church thanks to the initiatives of local bishops and religious orders, and in northern Europe it was particularly associated with processions of the Blessed Sacrament. The first Corpus Christi procession is attested in Cologne between 1265 and 1277.[12] At this early stage, the consecrated host was carried in a closed pyxis, but soon a glass-framed monstrance or ostensory (from the Latin monstrare and ostendere, which both mean “to show”) was used that exposed the sacrament for the adoration of the people. The universal observance of the feast was renewed by the Avignon Pope John XXII (r. 1316-1334) in 1317, when he promulgated the collection of canon law authorized by his predecessor Clement V (r. 1305-1314) and known as the Clementine Constitutions (Constitutiones clementinae).

The impact of the new feast on later medieval society can hardly be overestimated. Miri Rubins’s acclaimed study offers a lively account of how Corpus Christi “became the central symbol of a culture”[13] that was universally shared in Western Christendom until c. 1500. In the next installment, I will discuss elements of decline and of vitality in the Catholic liturgy in the period preceding the great rupture of the Protestant Reformation.

For previous installments of Father Lang’s Short History of the Roman Rite of Mass series, see:

- Part I: Introduction: The Last Supper—The First Eucharist

- Part II: Questions in the Quest for the Origins of the Eucharist

- Part III: The Third Century between Peaceful Growth and Persecution

- Part IV: Early Eucharistic Prayers: Oral Improvisation and Sacred Language

- Part V: After the Peace of the Church: Liturgy in a Christian Empire

- Part VI: The Formative Period of Latin Liturgy

- Part VII: Papal Stational Liturgy

- Part VIII: The Codification of Liturgical Books

- Part IX: The Frankish Adoption and Adaptation of the Roman Rite

- Part X: Monastic Life and Imperial Patronage

- Part XI: Reform Papacy and Liturgical Unification

- Part XII: The Impact of the Franciscans on the Roman Mass

Image Credit: AB/Wikimedia – Wenceslas Hollar – Elevation of the Host

Notes:

See the excellent overview of Helmut Hoping, My Body Given for You: History and Theology of the Eucharist (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2019), 175-210. ↑

See Gerard G. Grant, “The Elevation of the Host: A Reaction to Twelfth-Century Heresy”, in Theological Studies 1 (1940), 228-250. ↑

See Augustine Thompson, Francis of Assisi: A New Biography (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012), 62 and 83-86. ↑

Council of Agde (506), can. 18: CCL 148,202. See Andreas Amiet, “Die liturgische Gesetzgebung der deutschen Reichskirche in der Zeit der sächsischen Kaiser 922–102”, in Zeitschrift für schweizerische Kirchengeschichte 70 (1976), 1-106 and 209-307, at 82-84. ↑

Fourth Lateran Council, Constitutiones, 21. De confessione facienda et non revelanda a sacerdote et saltem in pascha communicandos (30 November 1215), in Enchiridion symbolorum definitionum et declarationum de rebus fidei et morum, ed. Heinrich Denzinger and Peter Hünermann, 43rd ed. (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2012), no. 812. ↑

There is some evidence for the use of unleavened bread in the Eucharist from the Christian East in the late sixth century. This has been the practice of the Armenian church practice since at least the synod of Dvin in 719 and may go back to the seventh century. See Jean Michel Hanssens, Institutiones liturgicae de ritibus orientalibus, Tomus II: De missa rituum orientalium, Pars prima (Rome: Apud Aedes Pont. Universitatis Gregorianae, 1930), 133-141. ↑

On these and related questions, see the outstanding contributions of Peter Browe which have been re-published in the volume Die Eucharistie im Mittelalter: Liturgiehistorische Forschungen in kulturwissenschaftlicher Absicht, ed. Hubertus Lutterbach and Thomas Flammer, Vergessene Theologen 1, 7th ed. (Münster: Lit Verlag, 2019). ↑

Ordo Romanus I, 48: ed. Andrieu, vol. II, 83. ↑

See Stephen J. P. van Dijk, O.F.M. and Joan Hazelden Walker, The Origins of the Modern Roman Liturgy: The Liturgy of the Papal Court and the Franciscan Order in the Thirteenth Century (Westminster, MD – London: The Newman Press – Darton, Longman & Todd, 1960), 369-370. ↑

On the institution of the feast, see Miri Rubin, Corpus Christi: The Eucharist in Late Medieval Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 164-199. ↑

See Jean-Pierre Torrell, Saint Thomas Aquinas, Vol. I: The Person and His Work, trans. Robert Royal (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1996), 129-136. ↑

See Theodor Schnitzler, “Die erste Fronleichnamsprozession: Datum und Charakter”, in Münchener Theologische Zeitschrift 24 (1973), 352-362. ↑

Rubin, Corpus Christi, 347. ↑