A 2019 Pew Research Study unveiled the unsettling news that only 31% of all Catholics believe in the Real Presence of Jesus Christ in the Holy Eucharist. Among Catholics who attend Mass once a week, 63% believe the bread and wine become the Body and Blood of our Lord. This survey revealed the need for the “dry bones” of Eucharistic faith to receive new life. The Lord exhorts the prophet Ezekiel with these words:

“Prophesy to these bones, and say to them, O dry bones, hear the word of the Lord. Thus says the Lord God to these bones: Behold, I will cause breath to enter you, and you shall live. And I will lay sinews upon you, and will cause flesh to come upon you, and cover you with skin, and put breath in you, and you shall live; and you shall know that I am the Lord” (Ezekiel 37:4-6).

In response to the “dry bones,” Bishop Andrew Cozzens (Diocese of Crookston), in collaboration with other clergy and members of the laity, is in the planning phases of a three-year period of Eucharistic revival that begins on June 19, 2022, the Solemnity of Corpus Christi. According to Bishop Cozzens in an interview with The Pillar, the theme of this revival is “my flesh for the life of the world” (John 6:51).

In November, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) published the document The Mystery of the Eucharist in the Life of the Church, which serves as a succinct summary of the Church’s doctrine on the Eucharist. This document is intended to be a point of departure to reignite catechesis and evangelization on the Eucharist in anticipation of the period of Eucharistic revival.

Three roots have contributed to the “dry bones” of Eucharistic faith: poor catechesis, liturgy poorly celebrated, and the lack of integration between the Eucharist and life.

Pope Benedict XVI offers in his first encyclical, Deus Caritas Est, a helpful framework on how we can contribute to the Eucharistic revival in light of the proclamation of the kerygma, the celebration of the leitourgia, and the exercise of diakonia. Benedict maintains that these “duties presuppose each other and are inseparable.”[1] This threefold responsibility of the Church helps us to address three roots that have contributed to the “dry bones” of Eucharistic faith: poor catechesis, liturgy poorly celebrated, and the lack of integration between the Eucharist and life.

First Things First: The Kerygma

The proclamation of the kerygma is the foundation of the Church’s mission, which from the beginning has been to preach Christ crucified (1 Corinthians 1:23). Pope Benedict notes that the core Gospel, which we are always called to proclaim, has been “the Kerygma of Christ who died and rose for the world’s salvation, the Kerygma of God’s absolute and total love for every man and every woman, which culminated in his sending the eternal and Only-Begotten Son, the Lord Jesus, who did not scorn to take on the poverty of our human nature, loving it and redeeming it from sin and death through the offering of himself on the Cross.”[2] In order for a renewal to take root, we must examine how and when we are proclaiming the kerygma. The kerygma must be the first priority of an authentic Eucharistic renewal.

Pope Francis has emphasized the primacy of the kerygma in his apostolic exhortation, Evangelii Gaudium. The kerygma must be the “center of all evangelizing activity and all efforts at Church renewal.”[3] The public ministry of the Lord began with the first step towards our reception of the kerygma: the call to repentance and conversion (Mark 1:14). Preaching on conversion, sin, and grace, accompanied by a greater availability of the sacrament of reconciliation, form an essential foundation for the reception of the kerygma.

Pope Francis says that catechesis focused on the kerygma should “express God’s saving love which precedes any moral and religious obligation on our part.”[4] Further, this catechesis is characterized by “joy, encouragement, liveliness and a harmonious balance which will not reduce preaching to a few doctrines which are at times more philosophical than evangelical.”[5] We cannot simply begin with Eucharistic doctrine until we have focused and renewed our efforts at the first proclamation of the kerygma. The people of God need to be reminded of the fundamental message that “God loved us first” (1 John 4:19).

Are the messengers who present this foundational truth filled with zeal and motivated by love in their presentation of the kerygma? During the inaugural Mass of his pontificate, Benedict XVI noted: “There is nothing more beautiful than to be surprised by the Gospel, by the encounter with Christ. There is nothing more beautiful than to know Him and to speak to others of our friendship with Him. The task of the shepherd, the task of the fisher of men, can often seem wearisome. But it is beautiful and wonderful, because it is truly a service to joy, to God’s joy which longs to break into the world.”

Preaching on conversion, sin, and grace, accompanied by a greater availability of the sacrament of reconciliation, form an essential foundation for the reception of the kerygma.

Bishops, priests, deacons, and lay people need to present the kerygma with joy and hope. Above all, it needs to be rooted in the lived encounter with our own friendship with Christ in the Holy Eucharist if we want the message to be received well. “We cannot give what we do not have.” The proclamation of the kerygma must flow out of one’s friendship with Christ in the Holy Eucharist.

Task 1: Eucharistic Kerygma

The Holy Eucharist is a sacramental sign of the core event at the center of the kerygma. According to St. Thomas Aquinas, “All things that are in the Eucharist pertain to represent the same reality, namely, the death of the Lord.”[6] The foundation of the Church’s doctrine of the Eucharist is that it is the premiere sacramental sign of Christ’s sacrifice on calvary. Aquinas argues that the Holy Eucharist, like the death of the Lord, effects “the grace by which the human being is incorporated into the mystical body.”[7] The sacrifice of the Holy Eucharist is ordered to communion. Finally, the Holy Eucharist perpetuates the Presence of Jesus Christ as evidence of his abiding love for humanity.

The USCCB’s document on the Eucharist emphasizes that the celebration of the Holy Eucharist re-presents the sacrifice of Christ on the Cross.[8] The bishops acknowledge that Eucharist is both a sacrifice and a sacrificial meal.[9] While the sacrificial nature of the Mass has primacy, this does not mean that it is opposed to the meal or banquet aspect of the Mass. As affirmed by the Council of Trent, the Catechism of the Catholic Church, St. John Paul II, and Pope Benedict, there is a clear emphasis upon the sacrificial character of the Eucharist. Is the re-presentation of Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross in the Mass clearly taught from the pulpit, in the classroom, and by the manner in which the liturgy is celebrated? The Second Vatican Council teaches that Christ instituted the Eucharistic sacrifice “in order to perpetuate the sacrifice of the Cross throughout the centuries until He should come again.”[10] The Eucharistic sacrifice reaches its culmination in communion.

All things that are in the Eucharist pertain to represent the same reality, namely, the death of the Lord.

–St. Thomas Aquinas

At a time when society seems more fractured and divided than ever, the Eucharist serves as a sign of ecclesial unity that can remind people of what communion can look like. St. John Paul II maintains the “Eucharistic Sacrifice is intrinsically directed to the inward union of the faithful with Christ through communion.”[11] At a time when individualistic autonomy reigns supreme in culture, the message of the communion brought about by the Holy Eucharist needs to be proclaimed with renewed vigor. The gift of sacramental graces, the increase of sanctifying graces, the strengthening of the life of virtue, and the grace offered to conquer sin and temptation are essential teachings that should be highlighted during this period of intentional Eucharistic focus.

Clergy, religious, and the lay faithful should promote the practice of frequent Communion, preparation for Communion, making sincere thanksgivings after Holy Communion, and the neglected practice of spiritual Communion. Awareness of the practice of spiritual communion has been revived as a result of the pandemic. Even beyond the pandemic, every household could find a prominent place to display an act of spiritual Communion in order to cultivate the constant desire for the Holy Eucharist.

Unfortunately, the majority of the discussion on the much-anticipated USCCB document on the Holy Eucharist within the media has centered upon “Eucharistic coherence,” narrowly framed as whether or not politicians in support of abortion should be able to receive Holy Communion. The USCCB, which never intended to focus solely upon this issue, offers the wider context for the Church’s teaching on receiving Holy Communion worthily. St. John Paul II articulates an essential component of the Church’s teaching on Communion. He notes that “the celebration of the Eucharist presupposes that communion already exists, a communion which it seeks to consolidate and bring to perfection.”[12] Holy Communion presupposes ecclesial communion.

On the one hand, the onus is upon each individual Catholic to discern with the aid of a well-formed conscience whether he or she is properly disposed to receive Communion. On the other hand, the Ordinary of a local church is called “to remedy situations that involve public actions at variance with the visible communion of the Church and the moral law.”[13] The bishop is entrusted with the role to “guard the integrity of the sacrament, the visible communion of the Church, and the salvation of souls.”[14] The tension that is delicately outlined here deserves greater clarity not merely in written word and speech. There is obvious confusion about the manner in which the consistent teaching on Holy Communion is implemented in practice. The bishops will need to continue to provide prophetic and charitable clarity as they attempt to accompany all people towards communion without compromising the teaching of the Gospel. The issue at hand is not about politicizing the Eucharist, but the koinonia, the spiritual communion that characterizes the Eucharist and the Church (1 Corinthians 10:16).

The Holy Eucharist is a precious gift that extends the mystery of the Incarnation. Jesus Christ is sacramentally present in the Eucharist. In the teaching of St. Paul VI, the Eucharist is the real and substantial presence par excellence.[15] Beyond the reaffirmation, emphasis, and clarity on the Church’s doctrine of the Real Presence, parishes and dioceses can promote devotion to Christ in the Eucharist through processions, holy hours, local Eucharistic congresses, and extended periods of Eucharistic adoration. The worship of the Lord in the Blessed Sacrament outside of the liturgy can help the faithful to appreciate the gift of the Real Presence, which is first given through the gift of the Mass. According to Pope Benedict, “The act of adoration outside Mass prolongs and intensifies all that takes place during the liturgical celebration itself.”[16]

Task 2: Participation in Leitourgia

Much of the immediate discussion following the publication of the Pew Research Study has focused on the need for better catechesis. The hope for Eucharistic renewal also depends on how the liturgy is celebrated. Pope Benedict XVI affirms a view espoused by one of the participants in the 2001 synod of bishops on the Holy Eucharist: “the best catechesis on the Eucharist is the Eucharist itself, celebrated well.”[17] The liturgy (lex orandi) itself is an expression of the Church’s teaching (lex credendi), so greater attention should be given to the manner in which the Holy Eucharist is celebrated.

Much of the immediate discussion following the publication of the Pew Research Study has focused on the need for better catechesis. The hope for Eucharistic renewal also depends on how the liturgy is celebrated.

The Fathers of the Second Vatican Council in continuity with previous magisterial teaching and the leaders of the liturgical movement have emphasized the need for the conscious and active participation of the faithful in the liturgy. The best means of fostering active participation is a renewed focus on improving the ars celebrandi. While there has been an attitude that wants to oppose the ars celebrandi and the active participation of the faithful, Benedict XVI considers the ars celebrandi the “best way” to achieve the active participation of the faithful.[18] During this period of intentional Eucharistic renewal, every minister should examine how he prepares for and participates in the Mass: the priest, the deacon, the servers, emcees, the lectors, the sacristan, extraordinary ministers of Holy Communion, ushers, and the faithful. Every gesture, word, and action should be carried out with reverence and focus.

Renewed attention should be given to the role of beauty within the liturgy. Recent popes have highlighted the via pulchritudinis in catechesis, evangelization, and the celebration of the liturgy. Benedict XVI notes that beauty is “an essential element of liturgical action.”[19] Parishes should examine the sacred artwork, the architecture, vessels, and vesture which are integral to their liturgical celebrations. The close connection between beauty and the liturgy demands that we periodically assess whether everything used in relation to the celebration of the Eucharist is beautiful. Denis McNamara, executive director of the Center for Beauty and Culture at Benedictine College, Atichison, KS, constantly emphasizes that something is beautiful when it reveals its ontology. Do all of these items used within the local ars celebrandi direct the faithful to appreciate the beauty of the heavenly Jerusalem or to encounter Jesus Christ, the Incarnation of beauty?

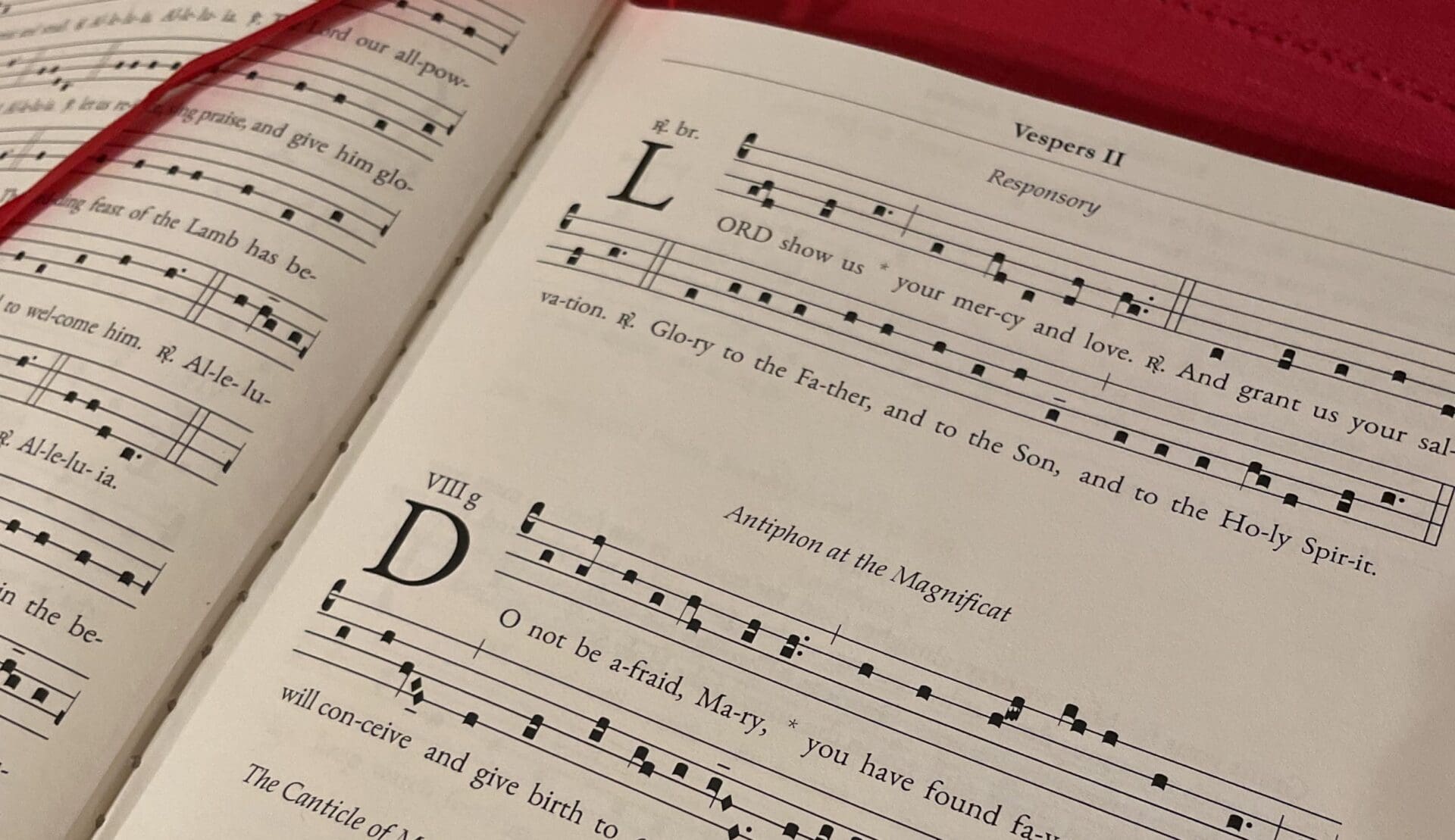

Particular attention should be given to sacred music because it is the supreme art within the ars celebrandi. Benedict XVI emphasizes that the “texts, music, and execution” demand particular attention because they “ought to correspond to the meaning of the mystery being celebrated, the structure of the rite and the liturgical seasons.”[20] Does the current repertoire of music used during the liturgy lead people to worship in accordance with the Church’s teaching on sacred music? Is there an effort to implement the use of more Gregorian chant with the liturgy?

Finally, greater efforts need to integrate more mystagogical catechesis. The faithful would all benefit from an increased understanding of the relationship between the liturgical rites and salvation history, the meaning of the varying signs and symbols of the liturgical rites, and finally the implications of the rite for one’s own life.[21] Preaching, catechesis, and ongoing faith formation are varying forums that could be utilized to assist the faithful to understand the liturgical year, liturgical gestures, and varying aspects of the liturgical rite with greater clarity. Greater understanding of the mysteries being celebrated can foster greater love for them.

Task 3: Diakonia, the Love that Fulfills the Law

Sacrifice is not the destruction of something within the context of the Eucharist. Sacrifice is ultimately about divinization—the transformation of the faithful by self-giving love.[22] The pioneers of the early liturgical movement emphasized the unity between the celebration of the liturgy and social action. Benedict XVI maintains the bold statement that a Eucharist that does not lead to charitable actions towards one’s neighbor is “intrinsically fragmented.”[23] A renewed emphasis upon the unity between the lex credendi and lex orandi ought to inform the lex vivendi.

Many communicants seem to reduce the Holy Eucharist to receiving an obligatory vitamin: the Eucharist is passively received because it is supposed to be good for my spiritual health. Exceptional catechesis and evangelization focused on unpacking the doctrine of the Holy Eucharist and a renewal of reverent, intentional, and beautiful liturgy can help provide a clearer revelation of Jesus Christ. When this occurs, it becomes easier for a person to be transformed actively by our encounter with the Eucharist. Benedict describes the radical transformation brought about by the Eucharist: “The Eucharist draws us into Jesus’ act of self-oblation. More than just statically receiving the incarnate Logos, we enter into the very dynamic of his self-giving.”[24] Through the Incarnation, God has become man and, via the divinization that can occur within the Eucharist, the human person enters into the life and love of God.

The ultimate fruit of a Eucharistic renewal is a Eucharistic life, which is marked by a selfless and loving diakonia.

The ultimate fruit of a Eucharistic renewal is a Eucharistic life, which is marked by a selfless and loving diakonia. Saints and Blesseds such as Teresa of Kolkata, Damien of Molokai, Vincent de Paul, Pier Giorgio Frasatti, Chiara Corbella Petrillo, or Carlo Acutis (patron of the USCCB revival’s first year) are witnesses to lives transformed by their encounter with the incarnate Logos. Their love for the Eucharist committed them to love others generously. Ratzinger characterizes charity as an essential companion to worship: “‘Caritas,’ care for the other, is not an additional sector of Christianity alongside worship; rather, it is rooted in it and forms part of it. The horizontal and the vertical are inseparably linked in the Eucharist, in the ‘breaking of the bread.’”[25] The Church’s teaching on the Eucharist is not simply abstract doctrine. The core of the Eucharistic doctrine focused on sacrifice is best translated into concrete self-giving love.

From Bones to Body and Blood

A fruitful Eucharistic revival needs to assist people in bridging the gap between Sunday worship and daily life. The mysteries of Christ’s life, which we encounter within the liturgy, ought to be translated into the daily rhythm of life. Through work, friendships, and interactions with family members, the Lord offers people opportunities to make sacrifices of themselves. There are ample opportunities to bring about communion through kindness, forgiveness, and mercy day in and day out.

Each member of the Body of Christ is invited each and every day to be a living witness to the Lord’s loving presence in the world. The new worship of Jesus Christ invites us to enter into his sacrificial love and become “bread that is broken” for others. Charity is essential to putting Christ’s flesh on these dry bones in need of revival. We need consistent and interconnected kerygma, leitourgia, and diakonia to make this clear.

Notes:

- Pope Benedict XVI, Deus Caritas Est (DCE), §25. ↑

- Pope Benedict XVI, Message for World Mission Day 2012, 6 January 2012. https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/messages/missions/documents/hf_ben-xvi_mes_20120106_world-mission-day-2012.html ↑

- Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium, 164. ↑

- Ibid., 165. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on the Sentences, book IV, d. 8, q. 1, a. 1, quaestiuncula 2, sed contra 2. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- USCCB, The Mystery of the Eucharist in the Life of the Church, §§8, 14, 16, and 25.↑

Ibid., §15. ↑

Sacrosanctum Concilium, §47. ↑

St. John Paul II, Ecclesia de Eucharistia, §16. ↑

Ibid., §35. ↑

USCCB, The Mystery of the Eucharist in the Life of the Church, §49. ↑

Ibid. ↑

Paul VI, Mysterium Fidei, §39. ↑

Sacramentum Caritatis (SCar), §66. ↑

Ibid., §64. ↑

Ibid., §38. ↑

Ibid., §35. ↑

Ibid., §42. ↑

See SCar, §64. Also see Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium, §166. ↑

See Joseph Ratzinger, Theology of the Liturgy: The Sacramental Foundation of Christian Existence, ed. Michael J. Miller, trans. John Saward, Kenneth Baker, S.J., Henry Taylor, et al., Collected Works 11 (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2014), 15. ↑

DCE, §14. ↑

Ibid., §13. ↑

Joseph Ratzinger, Jesus of Nazareth, Part Two. Holy Week: From the Entrance into Jerusalem to the Resurrection, trans. Vatican Secretariat of State (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2011), 129–30. ↑