As the papal reform movement was gaining momentum in the course of the 11th century, the papacy resumed its leading role in the development of the Roman Rite. Pope Gregory VII (r. 1073-1085) was crucial in this process—not, however, because of a far-reaching liturgical agenda (which he did not have), but rather because of his theological and canonical initiatives that set the tone for things to come.

Liturgy in the Pontificate of Gregory VII

A good source for Gregory VII’s liturgical ideas is Bernold of Constance, who stayed in Rome from 1079 to 1084 and between 1086 and 1090, and wrote a commentary on the Mass known as Micrologus de ecclesiasticis observationibus, a work that subsequently enjoyed considerable circulation and influence. Bernold reports the pope’s interest in studying apostolic traditions and his aim of restoring what was held to be Roman use in the age of Gregory the Great.[1] Against this backdrop, it may appear ironic that the Mass “iuxtam Romanam consuetudinem” (according to the Roman custom),[2] which Bernold expounds in the Micrologus, shows that the Rhenish Ordo Missae tradition had become an integral part of the rite followed by the pope and his curia. However, despite his repeated insistence on Roman custom (consuetudo), manner (mos), authority (auctoritas), and order (ordo), Bernold was not a naïve observer, and he was aware that not all of the prayers used at Mass were of Roman origin, for instance the Gallican invocation of the Holy Spirit, Veni, sanctificator (“Come, O Sanctifier”), at the offertory.

The Micrologus reports with disapproval that during the canon some priests interpolate prayers in the commemoration of the living (Memento, Domine) and of the dead (Memento etiam, Domine). Priests who insert the Incarnation into the anamnetic section of Unde et memories and extend the lists of the saints are likewise censured.[3] Bernold thus witnesses to the increasing insistence on the written ritual, as well as to priests being inclined to add to the received text.

A committed advocate for the Gregorian reform, Bernold does not seem to be overly concerned with establishing the “purely” Roman tradition, but rather with following the liturgical order of the contemporary papacy. Thus, the Micrologus echoes the policy of Gregory VII, who demanded that the Roman Rite, purged of recently introduced German customs, should be the norm for the whole Latin Church. Still, the pope only enacted very minor liturgical changes to implement this demand. Thus the liturgical sources of the Gregorian period show the continued impact of the Romano-Germanic tradition. However, the strong claim for papal authority, epitomized in the Dictatus papae,[4] was of long-term consequences for the Western Church in general and for the ordering of its divine worship in particular. Moreover, the (then-largely rhetorical) emphasis on investigating apostolic traditions and restoring the purity of ancient Roman observance helped create a mentality that was to have a lasting effect on conceptions of liturgical renewal.

Of immediate impact were the calls for local churches to follow Roman customs and observances, in order to guarantee doctrinal purity and ecclesiastical unity. Reform popes before Gregory VII had already made such demands in Italy with regard to the Ambrosian tradition in the north and the Beneventan tradition in the south. While Gregory refused to concede the use of the Slavonic language in territories he claimed for the Latin Church (Croatia and Bohemia), he did not insist on liturgical conformity in relation to the Greek and Armenian churches. Regarding Eastern Christianity, his main concern was a recognition of the primacy of the papacy.[5]

In continuity with his immediate predecessors, Gregory VII was persistent in his efforts to have the Hispanic (Mozarabic) Rite replaced by the Roman Rite throughout the Iberian Peninsula, with the intention of binding the re-conquered Christian territories to the See of Rome and forging the unity of Latin Christendom. This momentous change had been initiated in the Kingdom of Aragón in the pontificate of Alexander II (r. 1061-1073) through the activities of his legate Cardinal Hugo Candidus, and it was facilitated by Cluniac influence on monasteries in northern Spain. Gregory’s campaign was crowned with success when at the Council of Burgos in May 1080, King Alfonso VI of León and Castile decided to adopt the Roman Rite in his realm.[6] However, the substitution was not complete, and the Mozarabic liturgy continued to be celebrated in some places, especially in Toledo, its traditional center, which Alfonso captured in 1085.[7]

Liturgical Variety in the City of Rome

Present-day historians are inclined to highlight elements of diversity and innovation, and historians of the liturgy make no exception to this trend. However, it needs to be recognized that there are significant differences in the evolution of liturgical forms and genres. For instance, Mary C. Mansfield notes:

“Undoubtedly some rites hardly altered over many centuries. The canon of the mass, to take the most obvious example, remained stable because of its central importance from ancient times. Generally, as one moved outward from the canon first to the rest of the liturgy of the mass, then to the daily office, and finally to occasional rites like penance, one finds at each step more tolerance for alteration.”[8]

The core of the Eucharistic liturgy, inherited from its formative period between the fifth and the seventh centuries, showed remarkable continuity throughout the Middle Ages. Local variations concerned more peripheral aspects of the celebration of Mass, such as the choice of readings or the sanctoral calendar. Nonetheless, the importance of ritual in medieval society ensured that such disparities could provoke tension and even conflict.[9]

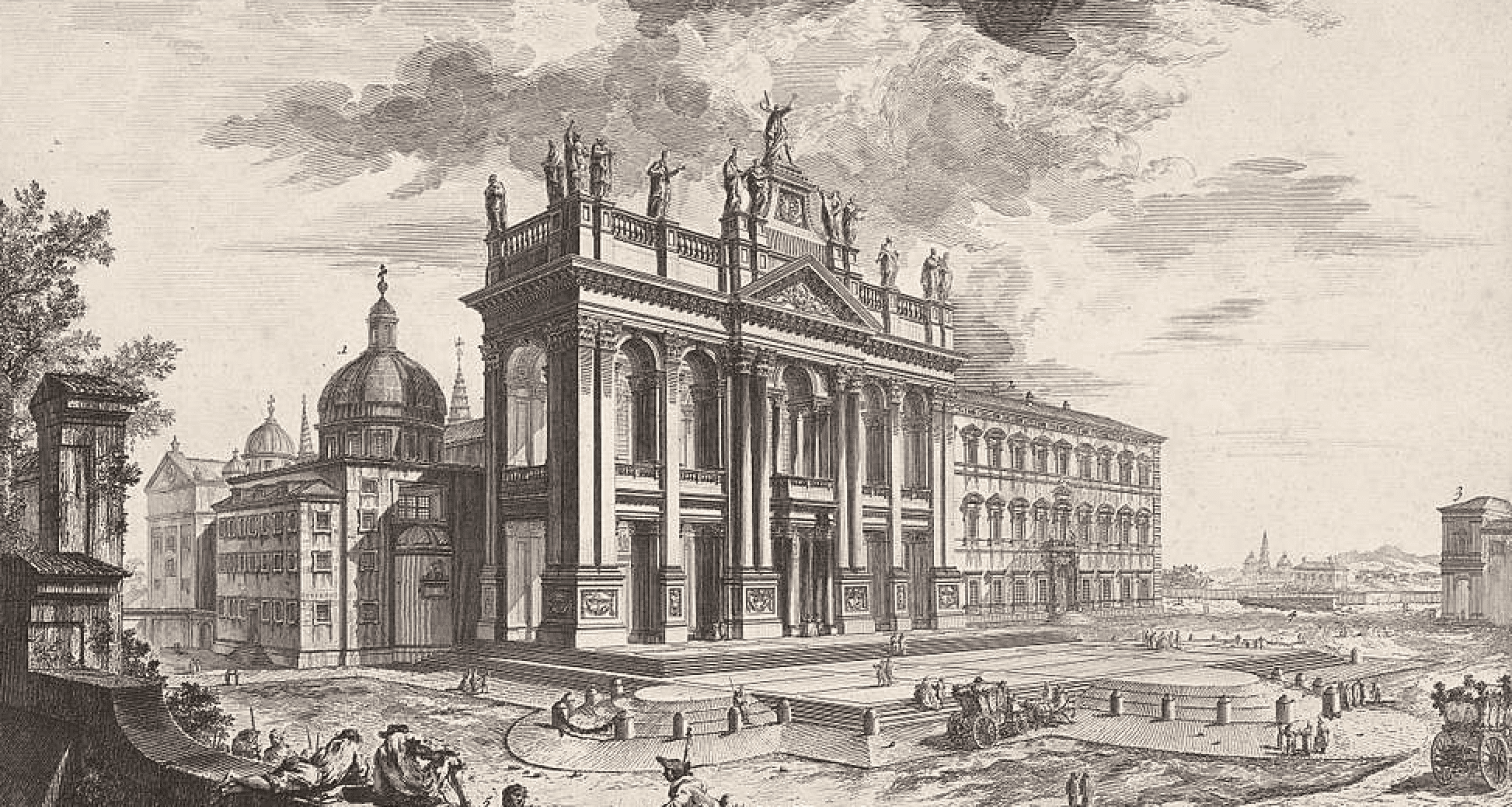

Within the stable framework established by the rite of Mass, there was no strict uniformity in particular ceremonies and observances even within the city of Rome. The Lateran basilica, the cathedral of the pope as bishop of Rome, which held the title “mother and head of all the churches in the city and the world” (omnium urbis et orbis ecclesiarum mater et caput), had no claim to impose its use on the many churches and monasteries of the city, and certainly not on St Peter’s in the Vatican, its rival for honor and prestige. At the time, the cycle of papal stational Masses was still a living reality, and proper customs (as well as local prerogatives) were maintained with tenacity.[10]

The Gregorian reform strengthened the power and prestige of the papal curia (often rendered “household” or “court”), and gradually the papal chapel, rather than the Lateran basilica, became the model for liturgical observance in Rome and beyond.[11] The curial liturgy was conducted with solemnity, especially in the splendid 13th-century setting of the chapel of St. Laurence in the Palace, known as the Sancta Sanctorum for its outstanding collection of relics. Beginning with the pontificate of Innocent III (r. 1198-1216), popes increasingly used the Vatican palace as a residence and its “great chapel” (capella magna) for liturgical celebrations. However, these ceremonial spaces were relatively small and did not allow for the processional elements that characterised stational liturgies in the churches of the city. Moreover, the papal court often travelled in this period and, for reasons of expediency, its liturgical use was given a standard form that could also be transferred to places with fewer resources, such as Anagni or Orvieto.

Still, the impact of the papal chapel remained geographically limited, and general conformity with Roman liturgical practice began to be observed throughout the Latin Church only with the rapid expansion of the new Franciscan Order in the 13th century, which will be the topic of the next instalment.

For previous instalments of Father Lang’s Short History of the Roman Rite of Mass series, see:

- Part I: Introduction: The Last Supper—The First Eucharist

- Part II: Questions in the Quest for the Origins of the Eucharist

- Part III: The Third Century between Peaceful Growth and Persecution

- Part IV: Early Eucharistic Prayers: Oral Improvisation and Sacred Language

- Part V: After the Peace of the Church: Liturgy in a Christian Empire

- Part VI: The Formative Period of Latin Liturgy

- Part VII: Papal Stational Liturgy

- Part VIII: The Codification of Liturgical Books

- Part IX: The Frankish Adoption and Adaptation of the Roman Rite

- Part X: Monastic Life and Imperial Patronage

Image Credit: AB/Rijksmuseum on picryl.com (CCO 1.0 Dedication)

Notes:

See Bernold of Constance, Micrologus de ecclesiasticis observationibus, 5, 14, 17, 43 and 56: PL 151,980CD, 986B, 988B, 1010AB and 1018BC. ↑

- Ibid., 1: PL 151,979A; see also the brief description of a priest’s Mass, ibid., 23: PL 151,992B-995C. ↑

- Ibid., 13: PL 151,985B-986A. ↑

- The Dictatus papae is a list of 27 brief statements of papal power, which are included in the register of letters of Gregory VII for the year 1075. ↑

- See H. E. J. Cowdrey, “Pope Gregory VII (1073-85) and the Liturgy,” in Journal of Theological Studies NS 55 (2004) 55-83, at 79-81. ↑

- See ibid., 78-79. ↑

- See Ludwig Vones, “The Substitution of the Hispanic Liturgy by the Roman Rite in the Kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula,” in Hispania Vetus: Musical-Liturgical Manuscripts: From Visigothic Origins to the Franco-Roman Transition, 9th-12th Centuries, ed. Susana Zapke (Bilbao: Fundación BBVA, 2007), 43-59. ↑

- Mary C. Mansfield, The Humiliation of Sinners: Public Penance in Thirteenth-century France (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1995), 160. ↑

- Vittorio Peri, “‘Nichil in ecclesia sine causa’: Note di vita liturgica romana nel XII secolo,” in Rivista di archeologia cristiana 50 (1974), 249-273, on uncompromisingly conservative attitude of the Roman deacon Nicola Magnacozza (Latinised: Maniacutius) in the 12th century. ↑

- See Cowdrey, “Pope Gregory VII (1073-85) and the Liturgy,” 57-58. ↑

- See Stephen J. P. van Dijk, O.F.M. and Joan Hazelden Walker, The Origins of the Modern Roman Liturgy: The Liturgy of the Papal Court and the Franciscan Order in the Thirteenth Century (Westminster, MD – London: The Newman Press – Darton, Longman & Todd, 1960), 80-87. ↑