“We are living here now as aliens and only for a time.”[1] Saint Cyprian’s insight is included in the Office of Readings for the last Friday of the liturgical year. It is a good reminder that in the world we are exiles, living as pilgrims.

That doesn’t mean, however, that Christians pass through the world as if they were immune to it, nor as frenzied tourists, snapping pictures at every monument they come across. Pilgrims pass through the land—on their way to the heavenly homeland, feeling the road beneath their feet, taking in its sights and sounds, its scents and flavors. A peregrinatus (pilgrim) is a grignoteur—a grazer, a nibbler, a gleaner. Christians engage the world, creation, and its culture through the gifts given by the Creator. Thus, the sacramental approach to the religious life—where we encounter divine realities through earthly things—is significant and, so, necessary. In virtue of the mystery of the Incarnation, the love of God is available to us: we recognize in Christ, “God made visible,” and so are “caught up through him in love of things invisible.”[2]

Deep Dig into Mystery

The significance of the senses became evident to me in the summer of 2017, when I had occasion to visit the Villa Romana del Casale in Sicily. It is an amazing archeological site that has its origin as early as the third century BC, though most of the visible construction is from the early fourth century AD. It undoubtedly predates the Edict of Milan (313), which signaled the end of the systematic persecution of Christians in the early Church.

Of particular note is the great meeting hall, the basilica, in which the master of the domus would receive guests, make official pronouncements, and entertain dignitaries. Standing on the main floor of the partially reconstructed building, I had the immediate sense of why Christians of the patristic period chose this majestic style of architecture as appropriate for the worship of Christ, the great King. This insight, it occurred to me, came to me through my senses, and it launched me into a continuing reflection on the impact of sensory feedback in Catholic ritual life.

The height and breadth of the building itself, especially in contrast with the dark, heavy, and squat nature of the surrounding structures, gave a sense of openness and grandeur. The natural sunlight streaming through the clerestory windows suggested heavenly illumination. The marble floor and the woodwork offered a sense of dignity and nobility. The situation of the master’s seat under the dome of the apse created a sonorously sweet spot from which every pronouncement would be clearly heard. The visual perspective, the spatial sense, and even the acoustics seemed to collaborate in an expression of the dignity and grandeur of the place.

The sacramental approach to the religious life—where we encounter divine realities through earthly things—is significant and, so, necessary.

About the same time, I was researching the earliest-known house-church at Dura-Europos, located on the Euphrates River in present-day Syria. I imagined myself accompanying the group of Easter Vigil electi, bowing down, physically humbling themselves, to enter the frescoed baptistery. What did they experience in their bodies, what did they see, smell, touch, as they passed painted vignettes of scripture stories on their way to the font—the healing of the paralytic, Jesus and Peter walking on the water, David defeating Goliath? I asked myself, “To what are people attuned in religious ritual today?”

A Sense of Archetypes

Sensory feedback, of course, is not limited to the realm of religion. In the 21st century, so-called “smart” devices talk back to us. Receive a message, they *ding.* “Type” a word, the keys vibrate with each stroke. Such feedback in the world of technology is called a “haptic.” iOS and Android devices include settings for haptic feedback in their parameter menus.

This type of sensory feedback did not emerge only with the introduction of smartphones in the 1990s. Traditional typewriters gave feedback, too. Human digits felt the relative resistance of the keys of the Royal typewriters on 1950s desks—and that sensation was very different from the advanced touch of the IBM Selectric, preferred in most office pools. The sound of the type striking the carbon, paper, and cylinder assured us that the letter had hit its target. The bell at the end of the line reminded us it was time to swing the carriage return bar from right to left. The smudges on the paper, the grainy erasures, and irregular pattern of a corrected word, the late night tappity-tap-tap of a last-minute term paper are all haptic aspects of the editorial experience.

Image Credit: AB/San Marcos Daily Record Negatives on Flickr

The term is also used in medicine. When a physician pokes and prods to determine our health, it is called a “haptic examination.” The doctor attends to feedback felt through the fingers of the hands and sounds of the lungs and heart conveyed through the diaphragm, bell, tubing, and headset of a stethoscope.

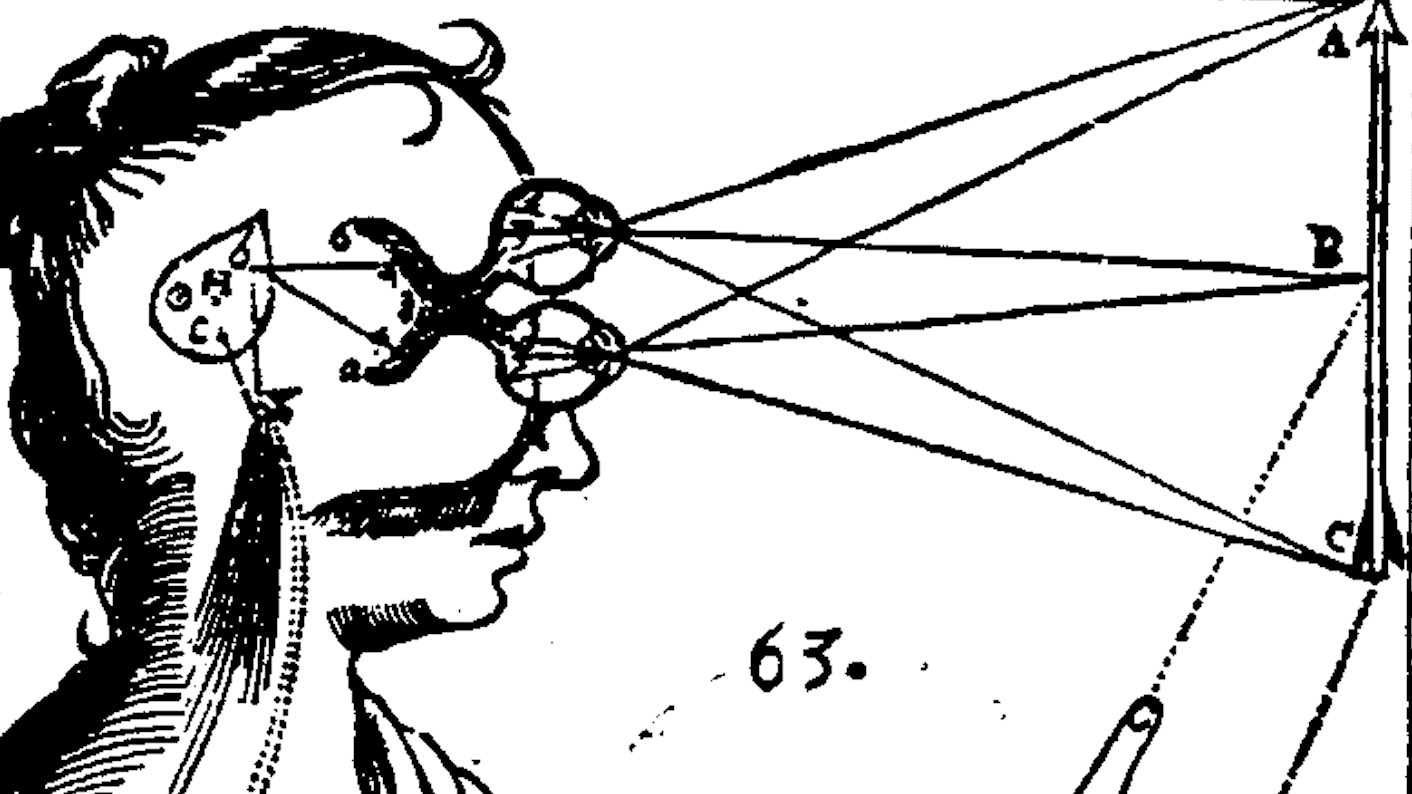

The word “haptic” has its origin in the Greek word hapto which means “to take hold of,” or “to touch.” In the world of computer technology, it refers to the audible or tactile sensations of an electronic device. When applied to the world of ritual, haptic includes all the stimuli received by our five senses: vision, olfaction (smell), audition (hearing), gustation (taste) and somatosensation, tactition (feeling).

Liturgy’s Sensitive Soul

The Catholic religion is founded on the mystery of the eternal God taking on human flesh; we call this the dogma of the Incarnation. It follows that the in-fleshed-ness of prayer is inseparable from faith. We are able to pray more fruitfully when we are aware of the way in which our bodies, our senses engage with prayer to the Divine. Reminders of this are prevalent in the Church’s teaching: “In the liturgy the sanctification of the man is signified by signs perceptible to the senses, and is effected in a way which corresponds with each of these signs; in the liturgy the whole public worship is performed by the Mystical Body of Jesus Christ, that is, by the Head and His members.”[3]

To what are people attuned in religious ritual today?

In the sacramental system we use material things, perceptible things, like water and oil, bread and wine, light and fragrance. These signs work through our human senses. The application of haptic experience to Catholic ritual is, thus, a natural and even necessary one—though in my estimation, an approach that has not received the attention it deserves. The better attuned we are to the liturgical and sacramental sensations, the more likely we are to appreciate the grace that is offered in our ritual prayer. When speaking of catechesis in Sacramentum Caritatis, Pope Benedict XVI reminds us, “More than simply conveying information, a mystagogical catechesis should be capable of making the faithful more sensitive to the language of signs and gestures which, together with the word, make up the rite” (64, emphasis added).

This is why, in the rite of ordination, the bishop says to the newly-ordained priest at the traditio, the handing over of the prepared chalice and paten, “Understand what you do, imitate what you celebrate, and conform your life to the mystery of the Lord’s Cross.”[4] But the bishop does not merely mean “know what’s necessary for the valid and licit celebration of the sacraments.” A network of meaning is at play: “A sacramental celebration is woven from signs and symbols.”[5]

Sacrosanctum Concilium, the Second Vatican Council’s Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, urges: “in order that the liturgy may be able to produce its full effects, it is necessary that the faithful come to it with proper dispositions, that their minds should be attuned to their voices, and that they should cooperate with divine grace lest they receive it in vain. Pastors of souls must therefore realize that, when the liturgy is celebrated, something more is required than the mere observation of the laws governing valid and licit celebration; it is their duty also to ensure that the faithful take part fully aware of what they are doing, actively engaged in the rite, and enriched by its effects.”[6] In so instructing their flock, pastors are not doing so merely in order that the faithful can judge whether the sacrament was properly celebrated. A conscious, aware Christian is able to pray more deeply, fully, and fruitfully—and sensibly.

When the Roman Missal at the beginning of the Sacred Paschal Triduum instructs the people to enter in fully, it is not merely to check a box in a spiritual “To-Do List.” “Pastors should, therefore, not fail to explain to the Christian faithful, as best they can, the meaning and order of the celebrations and to prepare them for active and fruitful participation.”[7] These exhortations apply to the fullness of the sacramental and liturgical expression in signs and symbols: to be aware of the scriptural foundation, perhaps to patristic allusions, and also to enter in with the whole human body. We carry around in our bodies the dying and rising of Christ.[8]

A Good Feel for Ritual

We should also be clear. An appeal for the recognition of haptics in the liturgy—to the sensory feedback the ritual provides—is not a call for the creation of new sensations or innovative experiences, or even of modifying the rites. The haptic feedback is already written into Catholic rites. Ours is a plea that they be noticed, followed, and appreciated—precisely because they communicate sacramental meaning and can make us more receptive to sacramental grace. Ritual gradually, gently forms us to worship, pray, and think with the mind of the Church.

At Marmion Abbey, the tower bells call us to prayer. The pattern of the peal corresponds to the solemnity of each liturgical day: on ferial days only two bells ring, three bells on certain feast days, five bells for solemnities. The largest bell is heard only when announcing the death of a member of the community or Church leader. It tolls at funerals. The haptic experience of genuine cast bronze bells is markedly different even from digitally sampled electronic bells. The click of mechanisms is heard, the tower vibrates, the sound resonates around the buildings.

The better attuned we are to the liturgical and sacramental sensations, the more likely we are to appreciate the grace that is offered in our ritual prayer.

An appeal for the recognition of haptics in the liturgy—to the sensory feedback the ritual provides—is not a call for the creation of new sensations or innovative experiences, or even of modifying the rites. The haptic feedback is already written into Catholic rites.

A priest from the south of France comments on the way that care for the church building, its furnishings, vessels, and linens can foster our awe and reverence: “Let your church be sparkling, so that the beauty of Jesus can bathe eyes and hearts. Cleanse, polish, and shine. Grace passes through that.”[9] Furthermore, he says, “Let there be beautiful chalices, just as there are beautiful cups for the Jewish Passover!” [10] He insists on clean, fresh linens, purificators, corporals, and altar cloths, vestments that are beautiful and well maintained. Such attention to detail contributes to the beautiful celebration of the sacred mysteries and communicates the value of what is being celebrated.

A triple example can illustrate how the careful celebration of the sacraments and sacramental rites can carry meaning over time—over the long-haul. Let’s follow a special couple, Sarah and Brandon, on their life’s journey together, beginning in Holy Matrimony. Keeping in mind that haptics are related to the feedback that comes through our senses, let us pay attention to what they (and we) feel, see, hear, smell, and taste at three privileged moments.

The Order of Celebrating Matrimony begins at the door of the church.

The minister “goes with the servers to the door of the church, receives the bridal party, and warmly greets them, showing that the Church shares in their joy.”[11] It is perhaps true that most wedding ceremonies do not begin like this. Our interest, however, in highlighting the meaning of these rites, must focus on what the Church asks us to do, rather than on what is most common or practical. In Catholic ritual, the meaning of the sacramental signs nearly always takes precedence over the pragmatic.

What do we notice as we are gathering at the door of the church? Undoubtedly, the people that have arrived are from different walks of life, different generations, perhaps even with different political persuasions. From a scattered world, they begin to gather here, at this meeting point. They even crowd in as the beginning of the ceremony nears. For St. John Chrysostom, the crowd itself was an essential part of the haptic: “Once again a feast! Once again a solemnity! Once again the Church adorns herself with a throng of children, the Church is filled with her children, the Church who loves her children!”[12] And soon they will join in the act of worship of God which the sacrament of Matrimony entails.

As these friends and family gather, their bodily bearing, their faces and voices, express excitement and joy, and perhaps some, too, in a more discreet manner manifest regret. They are dressed for the occasion, wearing cosmetics and fragrance. There are hugs, kisses, handshakes, and slaps on the back. Common news is spoken; secrets whispered. Laughter is heard: perhaps the characteristic cackle of Aunt So-and-So, not to be outdone by the humorous howl of Uncle Untel. No one outdoes the beauty, however, of bride and groom, with their special clothes, polished appearance, radiance, and mix of emotion.

The voice of the minister breaks through all of this commotion and calls the people together to enter in, to join hearts and voices. He puts this “local” joy into a universal context: “The Church shares your joy…in the presence of God…. May the Lord fulfill every one of your prayers.”[13]

As they enter into the church, the door itself is a sign of the liminal experience, the event that changes forever the lives of Sarah and Brandon, about to be united in Holy Matrimony: it is the crossing of a threshold. At the end of the ceremony, the couple passes this threshold again as witnesses to the world of what God has done for them.

The Order of Baptism of Children begins at the door of the church.

The celebrant “goes with the ministers to the door of the church…. The celebrant greets those present, especially the parents and godparents, recalling in a few words the joy with which the parents received their children as a gift from God, who is the source of all life and who now wishes to bestow his own life on them.”[14]

Sarah and Brandon return, perhaps a year after marriage, infant at the breast. Having entered into the public proclamation of their love for each other in this very spot, having received the blessing and prayer of the Church, they return now with the visible sign that their love has borne fruit. The life and love they share in Christ is now passed on to their offspring.

Family and friends gather again from all corners. New memories crowd into the vestibule or press around the doors of the church. We hope this experience includes the memory of the first time the couple paused at these doors, committing themselves to each other, witnessing love to the Church, hopeful of the future. They took their first steps into a new life which now bears life in turn. This family is different now, the circle of friends has expanded. The focus of prayer shifts from bride and groom to the future generations represented by their infant. This group is more familiar, more tactile, more knowing.

The baby is passed from arm to arm and embrace to embrace, uniting the group as never before. The newborn carries his own fragrance, and softness of skin, and unique sounds—gurgling and cooing and crying, too. In this spot, the child receives the Sign of the Cross for the first time, traced on the forehead by priest and parents as a pledge of eternal life. When he passes the door again, back into the world, he will carry the chrism-ed odor of Christ as a witness to the world.

The Order of Christian Funerals makes one final stop at the door of the church.

“The priest, with assisting ministers, goes to the door of the church” and greets those present with words of consolation.[15] It is many years later, we hope, that Sarah and Brandon mark a final moment at the door of the church. A life of regular sacramental participation has seen them pass this threshold many times, pausing briefly to scoop water from the font and tracing the Sign of the Cross over their bodies, as they enter to be nourished by the Word of God and the Bread of Life. Carried by loved ones for Baptism in the beginning of life, the beloved is carried to church a final time and entrusted to the merciful arms of God. The heaviness of the casket borne by pallbearers reflects the heaviness of heart.

The grieving family carries a different spirit on this day: a mixture of sorrow and gratitude. The hushed tones are subdued and reflective, the voices gentle and dignified. Memories wash over them: they are carried back in time. They ruminate over other days. They cling to one another in gestures of support and comfort. This family huddles together, not setting out alone, pursuing their own paths. Death, too, brings a unity of heart and shared experience.

Holy water is sprinkled on the coffin, reminiscent of that first baptismal bath, reminiscent of each blessing with holy water, each Eastertide renewal of Christian promises. Some droplets go astray, mingling with the tears of the family. Does God grieve, too? The white pall is spread over the body, recalling the purity of the baptismal garment. It is the original security blanket, a Christian security blanket—reminding those who see it that salvation, comfort, and protection have been promised by the Savior. These doorway rites are crowned with a final, dignified procession, through the nave to the altar: the meeting place of the human and divine.

Divinity Detailed

Every moment of liturgical prayer should be approached in this way; the effects of it are limitless precisely because the sacramental approach begins with what is genuinely human and weds it to the divine. The rituals of the Church are not contrived, fabricated, or invented. They are natural, lasting, and indelible.

Careful attention to details already written into our sacramental celebrations can help foster a richer, more meaningful experience. It can help us to be more attentive, more present, and more receptive. Engaging the senses of wonder and awe can lead to a greater response of thanksgiving for the marvels God has done, and a greater share in the grace the sacramental life offers.

Notes:

Cyprian of Carthage, On Man’s Mortality. ↑

Roman Missal (RM), Preface I of the Nativity of the Lord. ↑

Sacrosanctum Concilium (SC), 7. ↑

Roman Pontifical. ↑

Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1145. ↑

SC, 11. ↑

RM, Sacred Paschal Triduum, 2. ↑

2 Corinthians 4:10. ↑

“Que ton église soit rutilante pour que Jésus de sa beauté lave les yeux et les cœurs. Nettoie, frotte, et fais briller, par là s’immisce la grâce.” Michel-Marie Zanotti-Sorkine, Au diable la tièdeur, Paris: Editions Robert Laffont, 2012, 70. ↑

“De beaux calices et de belles coupes comme pour la Pâque juive!” Zanotti-Sorkine, 71. ↑

Order of Christian Marriage (OCM), 45. ↑

Homily 1 on Pentecost. PG 50, 453. ↑

OCM, 53. ↑

Order of the Baptism of Children, 35-36. ↑

Order of Christian Funerals, 159; see also 82. ↑