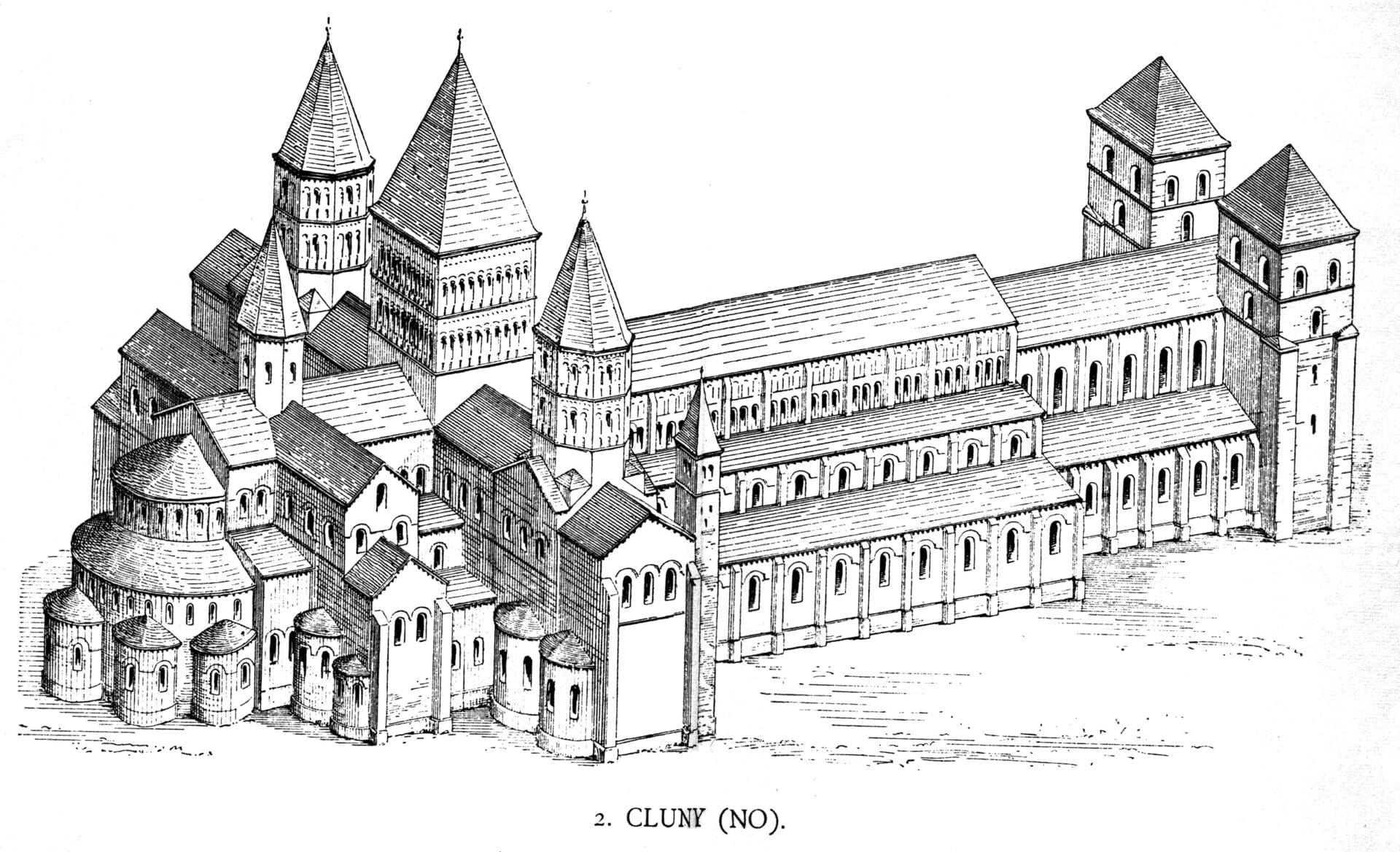

In the late ninth century, the city of Rome entered into a period of crisis, which has with some justification been called a “dark age” (saeculum obscurum) of the papacy, lasting well into the 11th century. Spiritual and cultural leadership was found north of the Alps, and this held for the liturgy too, which flourished in episcopal cities and Benedictine monasteries on both sides of the Rhine, such as Tours, Corbie, Metz, Mainz, Lorsch, Fulda, Reichenau, and St. Gall. New impulses came with the monastic reform movements, above all from Cluny, and with the German emperors of the Ottonian dynasty. Like their Carolingian predecessors, the Ottonians took a vivid interest in ecclesiastical matters, and showed themselves patrons of the liturgy in their realm, which also led to a flourishing of sacred architecture and art.

The Ordo Missae

The most momentous step in early medieval liturgical development was the organization of the recurring parts of the Eucharistic celebration into what is known to this day as the Ordo Missae (Order of Mass). The earliest vestiges of such an order are already found in many Gregorian-type sacramentaries, which begin with a separate section, “How the Roman Mass is to be celebrated” (Qualiter missa romana caelebratur). This instruction corresponds with the description of the papal stational liturgy in Ordo Romanus I (see installment VII of this series) and may go back to the late seventh century.

A subsequent step was taken with the collections of private prayers to be said by the celebrant at different moments of the rite. The earliest known example of such a collection is attested in the Sacramentary of Amiens (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, lat. 9432), dating from the second half of the ninth century.[1] Most of these texts, some of which consist of a single psalm verse, accompany and elucidate the spiritual meaning of particular ritual actions for the celebrant priest. They thus serve to sustain his personal piety and help the devout offering of the sacrifice of the Mass.

The Ordo Missae as a distinct liturgical genre flourished between the ninth and 11th centuries.[2] Contents and form varied considerably: for prayers, the opening word or phrase or the complete text is given; more or less detailed ritual instructions are sometimes provided,[3] and occasionally musical notation is added. The limits of this article do not allow for an adequate discussion of the widely received classification of the Ordo Missae of Bonifaas Luykx.[4] Some ordines could be excessive in their use of private priestly prayers, above all the ordo produced for Sigebert, bishop of Minden in northern Germany from 1022-1036. The text has achieved some notoriety since it was published in 1557 by the Lutheran theologian and historian Matthias Flacius Illyricus (1520-1575), and it became known as Missa Illyrica. Other ordines, however, are more measured in tone and less likely to overlay the traditional sequence of the rite of Mass. This testifies to an effort of pruning that resonates with views of the chronicler and Gregorian reformer Bernold of Constance (c. 1050-1100), who objects to the length and the private character of such prayers.[5]

Modern liturgical scholarship has tended to interpret the creation of the Ordo Missae as a departure from the “classical form” of the Roman Rite that was determined by the cultural needs of the Franco-Germanic people. Joanne Pierce and John F. Romano offer a balanced version of this critique: “The Roman Mass before this point was known for its soberness, simplicity, and straightforwardness. These [ordines Missae] filled out the framework of the Roman Rite with new prayers, psalms, and gestures, elaborating the ‘soft spots’ of the liturgy that had not previously received full elaboration, especially actions that occur without words. They imbued the Roman Eucharistic liturgy with new embellishment, drama, and allegorical symbolism.”[6]

This assessment is not without problems; first of all, the characterization of the Roman Mass as sober, simple, and straightforward. The ritual shape of the Mass, for which Ordo Romanus I is our key witness, certainly featured lavish and dramatic elements, especially in its processional parts, which were indebted to imperial ceremonial. Secondly, the elaboration of the “soft spots” can be understood as offering genuine development and even enrichment. For instance, the pontiff’s moment of silent prayer before he approached the altar[7] occasioned the recitation of Psalm 42[43], with the evocative antiphon “Introibo ad altare Dei…” (“I will go to the altar of God…”; v. 4).[8]

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, the Ordo Missae, rather than offering drama and embellishment, above all provided a coherent (and memorable) schema that facilitated the success of the “private Mass” with its much-reduced ceremonial. The shift towards the personal devotion of the offering priest gives some credence to the oft-repeated charge that the early medieval period saw a “clericalization” of the Mass and a detachment of the laity from its liturgical enactment.

The Creed at Mass

The last Ottonian ruler, the devout Henry II (king 1002, emperor 1014, died 1024), who took great interest in ecclesiastical matters, is known to liturgical historians above all for his initiative to insert the creed into the Roman Mass. The creed in question was that of the first two ecumenical councils of Nicaea (325) and Constantinople (381), which had been used as a baptismal profession of faith in the Christian East since the fourth century. Peter the Fuller, anti-Chalcedonian patriarch of Antioch (r. 471-488), is credited with the introduction of the creed into the Eucharistic liturgy, to be recited after the kiss of peace. In the Latin West, the creed became part of the Mass first in Visigothic Spain, after the conversion of King Reccared and his nobles to Catholic Christianity. At the third synod of Toledo in 589, it was decreed that the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed should be said with the filioque clause, affirming the procession of the Holy Spirit from the Father and the Son (filioque), at every Mass, in preparation for Holy Communion, preceding the Lord’s Prayer.[9] The Stowe Missal (c. 792-803), an important source for Irish liturgical use, places the creed after the gospel. Towards the end of the eighth century, Charlemagne had the singing of the creed (including the filioque) inserted after the gospel at the celebration of Mass in his Palatine chapel at Aachen. This decision was part of the Carolingian struggle against Adoptionist Christology in Spain. Pope Leo III (r. 795-816) approved of the use of the creed at Mass, though without the filioque, and he did not adopt the practice in Rome itself. The new custom spread slowly throughout the Carolingian realms and was commonly accepted in Franco-German churches by the 10th century.[10]

Staying in the city of Rome in 1014 for his coronation as emperor, Henry was surprised to find that, unlike in Germany, the creed did not form part of the rite of Mass and petitioned Pope Benedict VIII (r. 1012-1024) to add it. Subsequently, the creed was adopted in Rome on Sundays and major feasts in the liturgical year.

Conclusion

The shift from an oral to a written culture in the high medieval period gave the codified liturgical text a renewed importance. The pruned form of the Ordo Missae became normative for the celebration of the Eucharist and was incorporated into the 13th-century missal of the Roman curia. The next installment will show how the papacy, strengthened by the 11th-century reform movement, took charge again of the development of the Roman Rite.

For previous instalments of Father Lang’s Short History of the Roman Rite of Mass series, see:

- Part I: Introduction: The Last Supper—The First Eucharist

- Part II: Questions in the Quest for the Origins of the Eucharist

- Part III: The Third Century between Peaceful Growth and Persecution

- Part IV: Early Eucharistic Prayers: Oral Improvisation and Sacred Language

- Part V: After the Peace of the Church: Liturgy in a Christian Empire

- Part VI: The Formative Period of Latin Liturgy

- Part VII: Papal Stational Liturgy

- Part VIII: The Codification of Liturgical Books

- Part IX: The Frankish Adoption and Adaptation of the Roman Rite

Image Source: AB/Cluny Abbey at Wikipedia

Notes:

The digitized manuscript is accessible at https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9065879n. ↑

See Alain-Pierre Yao, Les “apologies” de l’Ordo Missae de la Liturgie Romaine: Sources – Histoire – Théologie, Ecclesia orans. Studi e ricerche 3 (Naples: Editrice Domenicana Italiana, 2019), 355-358. ↑

Because of the red ink commonly used for such instructions, they have become known as “rubrics” (from “ruber,” the Latin word for red). ↑

Bonifaas Luyxk, “Der Ursprung der gleichbleibenden Teile der heiligen Messe (Ordinarium Missae)” in Liturgie und Mönchtum 29 (1961), 72-119. ↑

Bernold of Constance, Micrologus de ecclesiasticis observationibus, 18: PL 151,989BC. ↑

Joanne M. Pierce and John F. Romano, “The Ordo Missae of the Roman Rite: Historical Background”, in A Commentary on the Order of Mass of the Roman Missal, ed. Edward Foley et al. (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2011), 3-34, at 21. ↑

Ordo Romanus I, 50. ↑

This psalm verse was already employed by Ambrose of Milan in his mystagogical catecheses for the newly baptised to evoke the approach to the altar of the Eucharist: De sacramentis IV,2,7, and De mysteriis 8,43. ↑

The Latin translation of the creed used in Mozarabic sources is different from the version later introduced in the Roman Rite. Interestingly, the loanword “homusion” is used, where the Roman version translates “consubstantialis”; see Marius Férotin, Le Liber Mozarabicus Sacramentorum et les manuscrits mozarabes, Monumenta Ecclesiae Liturgica 6 (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1912), 773. ↑

See the excellent documentation of Andreas Amiet, “Die liturgische Gesetzgebung der deutschen Reichskirche in der Zeit der sächsischen Kaiser 922–1023”, in Zeitschrift für schweizerische Kirchengeschichte 70 (1976), 1–106 and 209–307, at 222-228. ↑