In early October 2003, the Vatican announced that Mother Teresa was to be beatified later that month on October 19. I happened to be in Innsbruck, Austria, with fellow Notre Dame students on a year of study abroad. My American classmates, on October 18, floated the idea that we attend the beatification and, almost before I knew it, I was on the Via della Conciliazione outside St. Peter’s Square participating in the Mass. I have seen estimates that there were 250,000 people at that Mass, placing me near number 225,000. I could barely make out the whitish speck that was the pope at the altar, but thanks to the enormous video screens and speakers I was able to follow along. And despite many forgotten details, I remember well the satisfaction of joining with all those people in a single act of prayer. For all the limitations of praying in such a horde, I was there.

Or so I thought.

That’s not quite fair. I still do think I was at Mass with John Paul II; yet now, almost 20 years later, I also find it odd that my fellow worshipers and I took for granted that we were participating in the same Mass, celebrated so far ahead of us on the square. Remember: I was so far away from the altar that I was in a different country, beyond the borders of Vatican City and into Italy.

This adventure came back to mind as the Church in the United States groped its way through the coronavirus pandemic. Eucharistic celebrations made their way outside, priests and penitents pushed the maximum distance for effective absolution, and streaming became, for a while, a ubiquitous adjunct to Sunday liturgy. Creative solutions quickly allowed the faithful to see and hear the Church’s common prayer, but often these solutions seemed to stop short of asking how remote “participation” relates to the sort of participation required to fulfill one’s Sunday obligation or receive sacramental grace. And as some were content to rely on common sense and liturgical instinct to solve “unprecedented” problems, did anyone really believe the questions posed by this pandemic were entirely new or sui generis?

Yes, COVID did present unique challenges in the celebration of the liturgy, but, no, these challenges were not so unprecedented that the Church and her faithful could not—and cannot today—determine a prudent and principled course when it comes to celebrating the liturgy in times of duress.

The answer, in short, is yes and no. Yes, COVID did present unique challenges in the celebration of the liturgy, but, no, these challenges were not so unprecedented that the Church and her faithful could not—and cannot today—determine a prudent and principled course when it comes to celebrating the liturgy in times of duress.

Granted, we have no patristic treatise on how sacramental signification works via Zoom or Facetime, but certainly some weighty theologians in past centuries had addressed the fundamental question of what is required for an individual, body and soul, to be united to the liturgy and thus to participate fully in its graces. If we could identify a consensus from which to branch out into debates still unsettled, we could ensure that our present reasoning was organically developed from the previous tradition.

Traditional manuals of moral theology provide just such a resource from which to gain perspectives on liturgy in the information age. Such resources have, of course, their limits. The manuals are not exhaustive; they are not magisterial; they do not account for more recent discussions in theology. And yet despite all this, the orientations sketched out by the manuals invite us into conversation with the broader tradition. By taking our bearings from past thinkers we can chart the safest paths for future endeavors. Eschewing the temptation to stake out definitively proscriptive “no”s in understanding the proper celebration of the liturgy, we can consider what would be best to pursue with our “yes” in such matters. Because liturgy is vast and space is limited, I will focus on participation in Mass, first summarizing traditional requirements for participation, then evaluating modern experiments in that light.

Ligourian Measure

How do we know, from a physical standpoint, whether we’re actually participating in a Mass or other liturgical action? Do we measure this question in terms of physical distance? What about when there are obstacles to our viewing the liturgy? These and similar questions are the same which many priests and bishops have had to grapple with in the past two years of pandemic.

In responding to the basic question of participation, St. Alphonsus Liguori[1] constitutes the touchpoint for all other authors examined here. Since the Sacred Penitentiary declared all his moral opinions safe to follow, it is no surprise that Gury,[2] Lehmkuhl,[3] Slater,[4] Prümmer,[5] and Jone[6] do not venture too far afield from Ligouri’s distillation of our subject. This question was treated under moral theology because it dealt with a grave canonical obligation, namely that, in the current wording, “the faithful are obliged to participate in the Mass” (Canon 1247), or to “assist” at Mass (Canon 1248) on Sundays and holydays. Neither of those verbs can be accomplished by the faithful unless they are somehow present. But that raises another question: since we as composite beings may be present to a liturgy in more than one mode, which of these modes are necessary for full participation?

We might say that a Catholic is spiritually united to a liturgical action. This spiritual union can admit of various degrees but is arguably operative in the plenary indulgence (Handbook of Indulgences, particular grant §4) offered “to the faithful who devoutly receive” the pope’s blessing urbi et orbi “even if, because of reasonable circumstances, they are unable to be present physically at the sacred rite, provided that they follow it devoutly as it is broadcast live.” One might also consider providing an “offering to apply the Mass for a specific intention” (Canon 945) or appointing a proxy to contract marriage (Canon 1105) as types of spiritual union. (Though two parties must be present together to contract marriage, the exceptionally legal nature of matrimony allows a bride or groom to empower someone else to express consent on his or her behalf.) Yet the sense operative in the manuals’ discussions of the Sunday obligation is far closer to that of the urbi et orbi example. It consists of being able to direct one’s attention to the ceremonies and follow their progress.

Consequently, taking up a seat beside the altar would not matter if one then spent the Mass asleep, or painting, or teaching (Liguori §312). But this attention must always be tied to physical (i.e., bodily) presence at the rite being celebrated in order to fulfill the obligation to participate in Mass. “One would not hear Mass so as to satisfy the precept if he were stationed apart at a considerable distance from the place where it was being celebrated, even though he might be able to see and hear what was being done. He must be morally present so as to form one of those who are together hearing and offering up the Holy Sacrifice” (Slater, 171). This moral union with the liturgy demands that someone be physically “present in the place where the sacred action is taking place in such a way that he can be called one of those who are assisting and offering the sacrifice” (Gury, 341). In other words, moral presence combines with other criteria of physical proximity “such that one may be reckoned among the attendants at divine service” (Jone, 197).

Bodily nearness can, nonetheless, cover many deficiencies in a participant’s ability to perceive the flow of Mass directly. “For it suffices to hear Mass in the choir behind the altar, or through a window which leads into the church, even if one cannot make out the priest, provided that by means of the others assisting at Mass one can direct one’s attention to what is taking place” (Liguori). “Similarly, someone can assist at Mass from everywhere inside a church, provided that he can discern in some manner what is being done at the altar” (Lehmkuhl, 335); the building unites its occupants despite any space between them. “Even those who stand outside the church close to the door (even if it is shut) or who are in some neighbouring building” participate if they can follow the action through their own senses or through observation of others (Prümmer, 422).

But once outside the church, distance from other worshipers is far more likely to break their moral unity. Liguori, Gury, and Lehmkuhl posit at least 30 paces from the church or crowd without severing one’s bond with the liturgy, whereas a street or square might break the bond sooner (Slater), and a busy street more so than an empty one (Lehmkuhl). Jone’s more rigorous allowance of 60 feet is still generous for the onlooker who can see or hear through a door or window, though he also explicitly rules out radio as one’s means of perceiving the ceremonies. But a large crowd or army can unite one to the altar (Slater) thus ignoring limitations imposed by empty space.

Altogether, then, by requiring that the faithful be “physically and morally present” to participate in the Mass, the moralists are demanding that we be 1) bodily stationed within a certain range of the liturgy (physically present) but that we are also 2) attentive to the sacred action as 3) a reasonably identifiable part of the group physically present around that altar (morally present).

Ultimately, these considerations of physical and moral presence are trying to determine the limits of our ability to be “participants in a human mode.”

COVID Test

Ultimately, these considerations of physical and moral presence are trying to determine the limits of our ability to be “participants in a human mode” (Lehmkuhl). This human mode will not rest exclusively upon the powers of body or soul but will encompass the whole of the embodied spirit who is the human person. And with that as our goal we can examine various responses to pandemic conditions to test how well they manage to provide opportunities for full participation in body and soul.

Live streamed Masses were already on offer before the pandemic, and they proliferated quickly as bishops stopped public celebrations. As attempts to remain connected to the Church at large or even one’s parish church, various means of broadcasting the Mass certainly do allow one to unite in spirit with prayer conducted elsewhere. But whatever benefit is derived from that spiritual union, those too physically remote to form a moral union with the priest at the altar should not be said to participate in the full sense expected of Catholics each Sunday and holyday. This judgment is reinforced by the fact that Catholics unable to be present in a church are not canonically bound to view a Mass online in substitution for physical attendance.

And if completely remote viewing is insufficient to merely participate in a Eucharistic liturgy, we ought to consider it insufficient to remotely perform a ministry at Mass. Just as some clerics allowed designated godparents to speak their parts via phone or Skype, some tried to increase diversity of ministries and participation at Mass by patching in remote readers or musicians. Though better than a recording because at least synchronic with the sacred action, it is hard to see how someone could serve the liturgical assembly without assembling in the same place.

For instance, if the second reading or the Sanctus is entrusted to a non-participant, it seems that those who are physically and morally present are deprived of the opportunity to participate fully, for the parts that have been phoned in are in some sense lacking from the celebration. It would have been better to have a liturgical act clearly unified and complete than to prioritize diverse forms of union in a potentially incomplete set of diffuse actions.

Alert, perhaps, to the need to gather physically, others offered the creative solution of Mass in a parking lot or field. At its most cautious, this sort of celebration meant all attendees remained within their vehicles, windows up, to limit contagion. Worshipers might listen on an FM frequency or even follow a stream on electronic devices. This meant they were able to meet the benchmark of following the sacred action, even when perhaps none but the first row had a direct view of Mass. Yet Jone’s dismissal of radio aligns with my own suspicion that electronically mediated perception is not sufficient to connect us to the liturgy in a human mode—fully engaging body and spirit—without further elements to knit us into an assembly.

For example, someone sitting in the back seat of a car in the last row of the parking lot might have no direct means of perception and, with everyone sealed in separate vehicles, others’ reactions (such as bowing the head or making the sign of the cross) as the Mass progresses will also be unseen. Indeed, with so many steps to separate the congregation, the moral component of the physical assembly is undermined, perhaps irreparably. The effort to organize and attend parking lot Masses of this most extreme sort was certainly salutary, and an opportunity to receive Communion is no mean benefit. But wherever possible it would seem better to invite attendees to worship, distanced, outside their cars. This would degrade, perhaps, the ability to follow by electronic means. Still, by increasing the ability to perceive Mass through other participants’ actions, this alternative form of parking-lot worship would engender greater confidence that worshipers were truly gathered together, morally present with a group stretching to the altar.

Alone Together

When worship moved back indoors from the parking lots, many dioceses capped attendance at a certain percent of usual capacity within a church building. While some parishes added Sunday Masses to welcome all comers despite restrictions, others sought to accommodate more attendees in auxiliary or “overflow” locations, allowing the faithful to sit as a group and watch a live broadcast of the Mass.

Sometimes these auxiliary locations were immediately connected to the main body of the church and the audio/video feeds only made it easier to follow what one could have, with greater difficulty, perceived without them. For instance, people seated in a narthex could have heard the organ and seen when to stand, sit, or kneel, so the technology helped them unite more intentionally to an action in which even our traditional criteria would have said they were already participating.

But in other cases the overflow seating was in a completely separate section of the parish complex, like a parish hall or gym, sometimes even across the street from the church itself. In those cases, where attendees were connected to the sacred action by nothing but electronic means, it would seem the parish had not found a way to welcome them to Mass but had welcomed them instead to a place where they could view a livestream.

The ability to gather even for this opportunity is not to be discounted if the alternative is not assembling at all. Yet would it not be a more human form of gathering, and more in line with traditional views on participation, to sacrifice some audibility or visibility for the sake of maintaining a continuous congregation that extends from sanctuary to last worshiper?

The Church doubtless wants us to see and hear the liturgy. All the same, before worrying about the best vantage or following each prayer as the celebrant offers it, the Church requires that we gather, bodily, around an altar and join with all those standing round in offering ourselves with Christ.

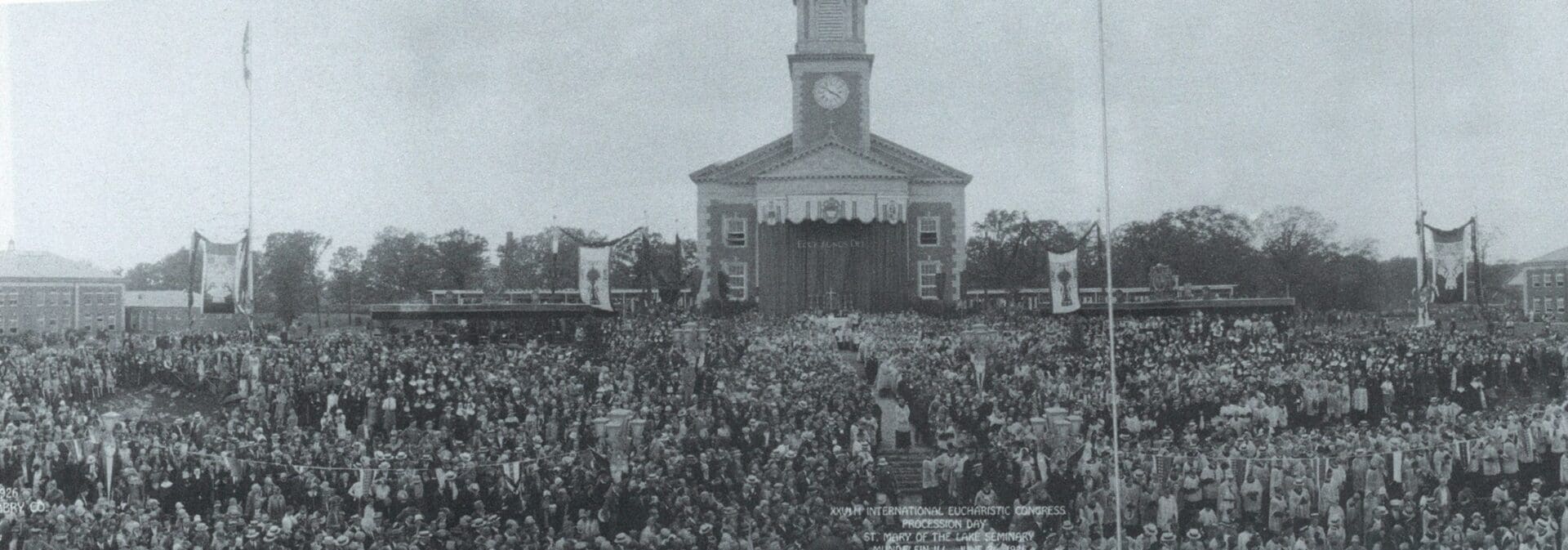

We should, then, prioritize physical gathering over technologically mediated perception. But standing “together” begins to lose its own plausibility after a certain point, even if our perception of Mass through our neighbors’ actions is assisted by microphones and screens. To return to my experience of Mother Teresa’s beatification, it seems that 250,000 people would constitute a large army. Recording-breaking papal crowds, on the other hand, estimated at 6 or 7 million, exceed worldwide American forces in the early years of World War II.

Where attendees were connected to the sacred action by nothing but electronic means, it would seem the parish had not found a way to welcome them to Mass but had welcomed them instead to a place where they could view a livestream.

At that point the criteria devised for the scale of a parish church simply break down. To reduce to the absurd, a congregation of 6 million spaced at 3-foot intervals in single file could begin at an altar in Paris and stretch most of the way to Moscow, with each person in line able to “follow” the flow of Mass as it rippled down the line. Yet checking off traditional criteria of moral and physical presence would not prevent credible participation from failing well before crossing the Rhine. Eventually a giant crowd loses its ability to unite in a single action in a way that we as tiny, limited creatures can truly soak in the significance of a liturgy through body and soul.

Keep It Together

Though I cannot challenge a pope’s judgment that a crowd of millions has fulfilled its obligation to attend Mass, I can question whether such large gatherings are the best way to promote fully human interaction with the liturgy and with one another.

As we set our sights past the pandemic we ought to keep this goal of human connection in mind so that our physical and moral presence is neither merely notional nor minimal but allows each of us to know, quite clearly, that we have gone to the altar of God.

Notes:

- de Ligouri, Alphonsus. Theologia moralis, rev. ed. Turin: Hyacinth Marietti, 1879.↑

Gury, Jean Pierre. Compendium theologiae moralis, 8th ed. expanded by Antonio Ballerini. Rome: Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith, 1884. ↑

Lehmkuhl, August. Theologia moralis. 5th ed. Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder, 1888. ↑

Slater, Thomas. A Manual of Moral Theology, 5th ed. London: Burns, Oates, and Washbourne, 1925. ↑

Prümmer, Dominic M. Handbook of Moral Theology, 5th ed. Transl. Gerald W. Shelton. Cork: Mercier, 1956. ↑

Jone, Heribert. Moral Theology, 18th ed. Translated by Urban Adelman. Westminster, MD: Newman, 1962. ↑