September 13, 2021, marks the centennial of the birth of Alexander Dmitrievich Schmemann. If you have never heard of him, it is probably because he inhabited a world little known to people in the West, including the religiously observant; yet, this individual and his world have much to offer us in an understanding of God and his Kingdom.

Schmemann was a Russian Orthodox priest and theologian who turned the conventional approach to liturgical study inside out. His work spawned a great deal of liturgical and pastoral renewal in the Orthodox Church, especially in North America. This article will give a brief account of his life and sketch out the basic features of his vision of the liturgy. It will become plain that, although Schmemann deals with the Byzantine Rite, his key insights remain significant for Christians of all traditions.

A Liturgist’s World

Alexander Schmemann was born in 1921 in Estonia into a Russian family, with Baltic German ancestors on his father’s side. When he was a young child, the Russian Revolution forced his family to leave home. They eventually settled in Paris, at that time home to tens of thousands of Russian emigrants. Young Alexander received his primary education at a Russian military school in Versailles and then transferred to a gymnaziya (high school). Not wanting to remain in isolation from the surrounding culture, he completed his education at a French lycée and at the University of Paris.

From his teenage years Schmemann was involved in Paris’s St. Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, where he served as an altar boy and subdeacon. During the Second World War he studied at the Orthodox Theological Institute of St. Sergius in Paris (1940-45). It was there that Schmemann’s worldview was essentially shaped.[1] In 1943 he married the German-born Juliana Ossorguine (1923-2017), a student at the Sorbonne whose family, like his, were emigrant Russians.[2] Upon graduation he remained at St. Sergius to teach Church history and was ordained a priest in 1946.

Real liturgical theology is theology that springs directly from the liturgy, that is implicit in the Church’s liturgical experience. Its practitioners, the real “liturgists,” are not academic theologians in their studies but ordinary people in the pews.

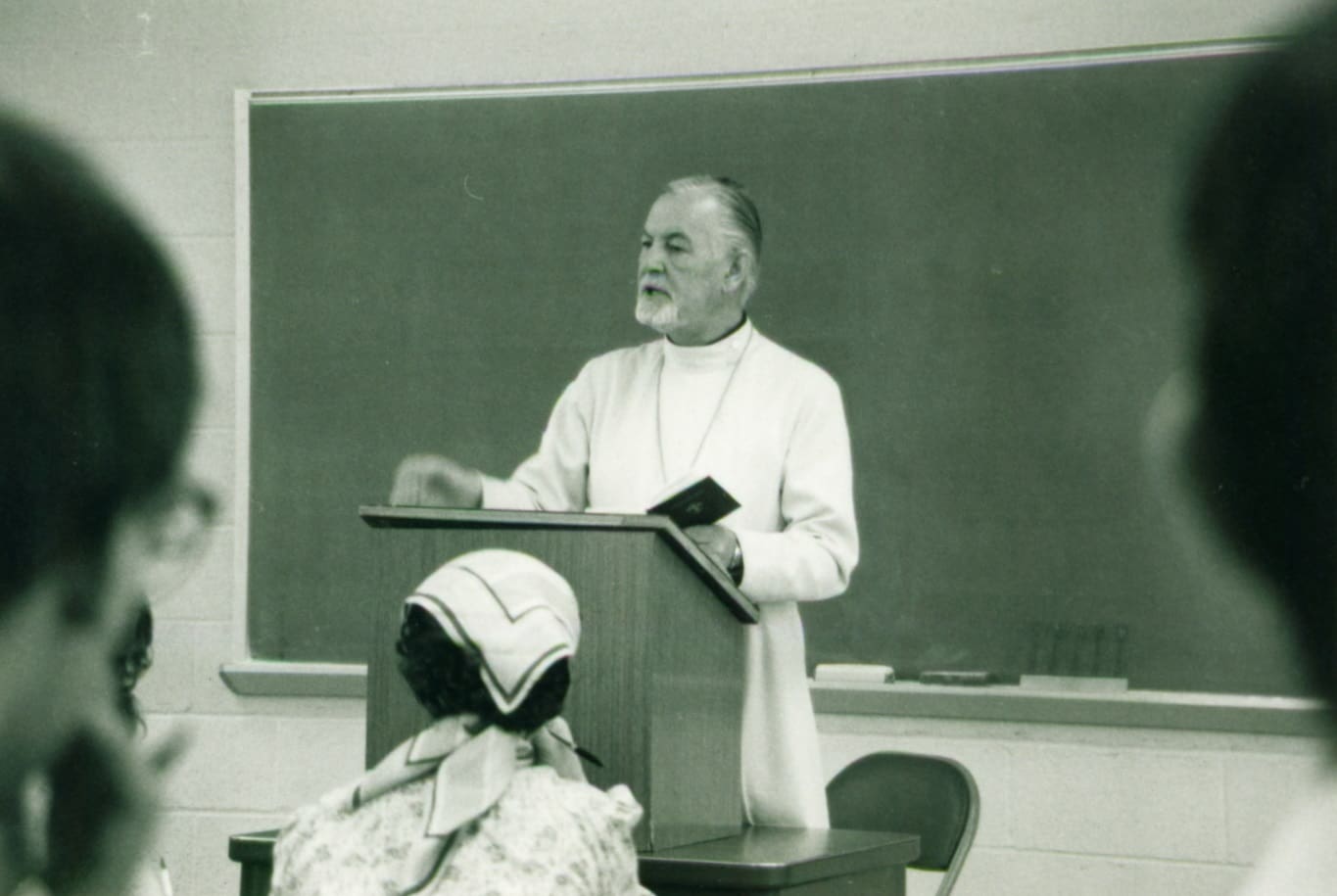

In 1951 Father Alexander accepted an invitation to join the faculty of St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary, which at that time was ensconced in a few modest apartments in Manhattan. Soon he became recognized as a leading authority on Orthodox liturgical theology. Having maintained ties in Paris, he earned a doctorate from St. Sergius in 1959. When St. Vladimir’s relocated to the Crestwood section of Yonkers, New York, in 1962, Schmemann accepted the post as dean, which he held until his death from cancer on December 13, 1983.

Many activities occupied Schmemann’s time in America: family life, teaching, seminary administration, ecclesiastical politics,[3] weekly sermon broadcasts in Russian on Radio Liberty (which gained a broad audience in the Soviet Union, including the famous dissident Alexander Solzhenitsyn), speaking engagements at pan-Orthodox and ecumenical gatherings, and, of course, writing numerous articles and books. His major liturgical studies are: Introduction to Liturgical Theology (1966), For the Life of the World (1973), Of Water and the Spirit (1974), and The Eucharist (posthumous, 1988), all published by St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press. As time moved on, Schmemann became less and less interested in academic theology, preferring instead “to write for the people, not for theologians.”[4] The memoirs of his last ten years, published in 2000, are scattered with comments about how pleased he was when ordinary people complimented his writings.

Visionary Look at Prayer

Liturgical theology, as the term is generally understood, has its roots in the collaboration and mutual influence of Russian and Western (especially French) scholars in the 20th century. The Orthodox theologians who settled in “Russian Paris,” including Schmemann, engaged with the great Catholic figures of Ressourcement, a theological movement of the 1930s to 1950s that set the stage for the Second Vatican Council. Its principal exponents, many of them noted Dominicans and Jesuits, sought to breathe new life into the soul of Catholic theology by returning to its sources, particularly the Church Fathers, both Western and Eastern.[5] At that same time, another movement of renewal, the Liturgical Movement, was underway in the West.[6] Its members mobilized Ressourcement concepts, drawing from old, significant wells long forgotten. “It was from that existing milieu,” writes John Meyendorff (Schmemann’s successor as dean of St. Vladimir’s), “that Father Schmemann really learned ‘liturgical theology,’ a ‘philosophy of time’ and the true meaning of the ‘paschal mystery.’”[7]

Until the mid-20th century, the study of the liturgy in Orthodox religious schools was largely focused on liturgical rubrics. The case was not very different in the Catholic Church: liturgical studies were assigned to moral theology, canon law, and, for the history of the liturgical rites themselves, Church history. With the impact of the Liturgical Movement, the liturgy became a specific area of theological studies. Schmemann perceived a danger in this. He thought it bad enough that theology had become confined to academia and thus cut off from both worship and piety, but now the liturgy becomes just one among many objects to evaluate or resources to mine. Liturgical theology, as Schmemann conceives it, is neither liturgiology—the study of the development of liturgical rites, usually liturgical books—nor a theology of liturgy. Rather it is theology that springs directly from the liturgy, that is implicit in the Church’s liturgical experience.[8] Its practitioners, the real “liturgists,” are not academic theologians in their studies but ordinary people in the pews, as personified by Aidan Kavanagh’s “Mrs. Murphy.”[9]

The liturgy, to Schmemann’s mind, is the very condition for theology; it is what makes “talk about God” possible. That is because God reveals himself and acts in the liturgy.

This notion of liturgical theology as a true method of doing theology, rather than one branch of theology among others, did not originate with Schmemann.[10] It was Schmemann, however, who contributed most to working out the concept and spreading it beyond the Orthodox world. Few, if any, liturgical scholars in Schmemann’s time (or now) would have disputed that the liturgy is a main source of theology, indeed theology’s source par excellence, but for Schmemann even that is not saying enough. The liturgy, to his mind, is the very condition for theology; it is what makes “talk about God” possible. That is because God reveals himself and acts in the liturgy.[11] Useful though it may be, say, to compare the Greek and Slavic ways of celebrating the Eucharist, or to trace the evolution of initiation rites, hymnography, liturgical feasts, etc., Schmemann’s concern goes deeper: What can these things teach us about a proper worship of God, about what it means to give thanks, to bless, to lament, to consecrate, to offer sacrifice? Hence his definition of liturgical theology as “the elucidation of the meaning of worship.”[12] From this perspective, it becomes clear that the object of liturgical theology is not any particular liturgical rite or liturgy in general but theology, that is, the revelation of Christ as believed and understood in the Church, in the actual practice of her worship, where Scripture and Tradition come alive.[13] Because its ultimate concern is with what lies behind the words, forms, gestures, and symbols (both old and new), liturgical theology has its place even beyond the historically “liturgical churches.”[14]

Sacramentally Real

Schmemann had what is sometimes called a sacramental imagination. One sees this in his running polemic against “religion,” meaning “one part of life, one sacred compartment as opposed to all the rest considered as profane.”[15] In this respect we might call him a mystic, ever attuned to the spiritual realities that underlie the commonplace. This way of looking at the world, of seeing the “natural” infused with the “supernatural”—or better: all reality “charged with the presence and promise of Christ”[16]—formed Schmemann’s challenge to contemporary secularism.[17] It also explains why his liturgical theology has been succinctly described as “a lived eschatology.”[18] It is always focused on the future Kingdom of God that is already experienced in this world. Schmemann defines the Church as the “place of the revelation of the Kingdom”[19] and “the Kingdom of God among and inside us.”[20]

The Christian experience of the Kingdom should foster the goal of liturgical theology as Schmemann describes it: to reintegrate theology, liturgy, and piety within one fundamental vision.[21] David Fagerberg deftly lays bare what is at stake: “Separate liturgy from theology and piety, and we get human ritual; separate theology from liturgy and piety, and we get a religious philosophy; separate piety from liturgy and theology and we get idiosyncratic religiosity.”[22]

The most concrete manifestation or “epiphany” of the Church as the Kingdom is the celebration of the Eucharist, in which we experience a foretaste of the Messianic banquet that awaits us with the fulfillment of all things in Christ. In this fashion, Schmemann calls the Eucharist the “sacrament of the Kingdom,” a relationship signified by the opening proclamation of the Divine Liturgy: “Blessed is the Kingdom of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, now and ever and unto ages of ages.”[23] Expanding on this point, he bemoans the longstanding neglect in sacramental theology of the eschatological dimension of the Eucharist, that is to say, the Eucharist seen as “the Church’s entrance into heaven, fulfillment at the table of Christ, in his Kingdom.”[24]

Another aspect of Schmemann’s liturgical theology is derived in part from the work of St. Sergius’s Nicholas Afanasiev, namely, eucharistic ecclesiology.[25] This model of the Church unites into a single concept two definitions of the body of Christ as found in the teaching of St. Paul. On the one hand, the body of Christ is the sacrament of Christ’s Body and Blood, partaken by the faithful, thus uniting them into one ecclesial body (1 Corinthians 10:16-17); on the other hand, the body of Christ is the Church (1 Corinthians 12:27-28). The Fathers of the Church were particularly occupied with the relationship between the eucharistic body and the mystical body of Christ, with how the Eucharist makes the Church. In the transition from patristic to scholastic theology in the early medieval period, attention shifted to the question of how Christ becomes really present in the sacrament through the action of the priest, that is, how the Church makes the Eucharist.[26] In consequence, as Schmemann notes with regret, both the “ecclesiological meaning of the Eucharist” and the “eucharistic dimension of ecclesiology” fell into general oblivion.[27]

Ecclesial Trinity

Eucharist, Church, and Kingdom are inseparable, indeed triune. In keeping with his distaste for “religion” (as opposed to a real Church and a real liturgy), Schmemann criticizes the “‘sacralization’ of Christian worship” whereby the Eucharist “was celebrated on behalf of the people, for their sanctification—but the Sacrament ceased to be experienced as the very actualization of the Church.”[28] Furthermore, he writes, “The whole history of the Church has been marked by pious attempts to reduce the Eucharist, to make it ‘safe,’ to dilute it in piety, to reduce it to fasting and preparation, to tear it away from the church (ecclesiology), from the world (cosmology, history), from the Kingdom (eschatology).”[29] Thus he expresses his vocation as a liturgical theologian in terms of a “fight for the Eucharist” against the reductionist assaults of clericalism and secularism.[30] The Eucharist is the sacrament of the Church and therefore of the Kingdom, not “one of the means of sanctification”[31] subject to clerical gatekeeping, on the one hand, or, on the other, to “such principles as the famous ‘relevance,’ or ‘urgent needs of modern society,’ ‘the celebration of life,’ ‘social justice.’”[32]

The Fathers of the Church were particularly occupied with the relationship between the eucharistic body and the mystical body of Christ, with how the Eucharist makes the Church.

This intuition led Schmemann to strive to improve the standard of liturgical celebration at the parochial level: “The liturgy is, before everything else, the joyous gathering of those who are to meet the risen Lord and to enter with him into the bridal chamber. And it is this joy of expectation and this expectation of joy that are expressed in singing and ritual, in vestments and in censing, in that whole ‘beauty’ of the liturgy which has so often been denounced as unnecessary and even sinful.”[33] The bane of Christian worship has been minimalism in its various forms, whether by doing the bare minimum necessary for a “valid” sacrament (an idea inherited from the “theology of liturgy”), or by reducing the liturgy’s essentially corporate nature to private family events. Schmemann deplores the “liturgical decadence” whereby, for example, “today it takes some fifteen minutes to perform [Baptism] in a dark corner of a church, with one ‘psaltist’ giving the responses, an act in which the Fathers saw and acclaimed the greatest solemnity of the Church….”[34]

Reform vs. Rediscovery

For all his efforts to highlight the deeper themes of the liturgy which had suffered eclipse, Schmemann does not advocate broad ritual reform. On the contrary, he repudiates the view of other scholars who interpret him as preparing the grounds for a liturgical reform that would restore the “essence” of the liturgy: “Yes, our liturgy, to be sure, carries with it many non-essential elements, many ‘archaeological’ remnants. But rather than denouncing them in the name of liturgical purity we must strive to discover and to help others discover the lex orandi, which none of these accidental ingredients has managed to obscure. The time thus is not for external liturgical reform but for a theology and piety drinking again from the eternal and unchanging sources of liturgical tradition.”[35]

Here we may pause to note a significant difference between the application of liturgical theology in the Western and Eastern Churches. In the West, ideas that scholars conceived in their studies have had a direct influence on the liturgy, notably with the reform of the Roman Rite after Vatican II. Old rites were abandoned and replaced by new, revised rites. The experience of the East has been different: the manner of liturgical celebration has changed—the music is often simpler and less intrusive, the “secret” prayers are sometimes said audibly (this was Schmemann’s practice), the laity receive the Eucharist more often than in the past—but the prayers and ceremonial remain largely untouched. Liturgy is still thought of as received from tradition rather than planned and imposed from above.

The Liturgical Movement impressed Schmemann with its attention to the liturgy as a real participation in the Paschal Mystery, prefigured in the Old Testament and accomplished in Christ’s life, death, Resurrection, and Ascension. This is possible because the Incarnation of the divine Son brought eternity into time, thereby transcending time and giving it new meaning. Schmemann speaks of the liturgical experience of time as “time that is eschatologically transparent.”[36] As the sacrament of the Kingdom, the Eucharist manifests the Church “as the new aeon; it is participation in the Kingdom as the parousia, as the presence of the Resurrected and Resurrecting Lord.”[37]

“The only real fall of man is his noneucharistic life in a noneucharistic world.”

Eucharistic Heart

This real entrance into the Kingdom or life in the coming age should inspire the faithful to share in the work of God here and now. Schmemann speaks of a “movement of ascension” intrinsic to the liturgy that draws us up to the throne of God in his Kingdom, as well as a “movement of return” that transforms the Church into mission, a mission of service to the world, drawing the world into the Kingdom: “The Eucharist is always the End, the sacrament of the parousia, and yet it is always the beginning, the starting point: now mission begins.”[38]

Even if until now you had never heard of Father Alexander Schmemann, the odds are very good that you would have heard that the word “Eucharist” derives from the Greek word for thanksgiving. With respect to Schmemann’s liturgical contribution, a Byzantine Catholic priest writes, “We are made to feel that we truly do want to worship.”[39] Higher praise for a liturgical scholar is hard to imagine, and Schmemann himself tells us why: “The only real fall of man is his noneucharistic life in a noneucharistic world.”[40]

Notes:

John Meyendorff, Afterword to The Journals of Father Alexander Schmemann, 1973-1983, trans. Juliana Schmemann (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2000), 347. ↑

- Their marriage bore the fruit of three children. Juliana would have a long career teaching in New York girls’ schools. ↑

One of Schmemann’s proudest achievements was helping to secure autocephaly, or self-governance, for the Orthodox Church in America, which until 1970 had been part of the Moscow Patriarchate. ↑

Schmemann, Journals, 93. ↑

Ressourcement (loosely, a “re-sourcing”) was a reaction against traditional Neo-scholasticism, perceived as a distortion of the legitimate method of St. Thomas Aquinas, characterized by a narrow intellectualism that diminishes the glory and mystery of revelation to rationalistic categories. A good introduction is Ressourcement: A Movement for Renewal in Twentieth-Century Catholic Theology, ed. Gabriel Flynn and Paul D. Murray (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2012). At the same time, Orthodox theology was undergoing its own version of ressourcement called the “neo-patristic synthesis.” ↑

See Thomas M. Kocik, Singing His Song: A Short History of the Liturgical Movement, Revised and Expanded Edition (Hong Kong: Chorabooks, 2019). ↑

Meyendorff, Afterword to Journals, 347. ↑

An analogy can be made between the liturgical theologian and the religious poet. The religious poet is not a poet who treats of religious matters only (a poet of religion), but one who treats the whole subject of poetry in a religious spirit. ↑

Aidan Kavanagh, On Liturgical Theology (New York: Pueblo, 1984). ↑

See Job Getcha, “From Master to Disciple: The Notion of ‘Liturgical Theology’ in Fr. Kiprian Kern and Fr. Alexander Schmemann,” St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 53, nos. 2-3 (2009): 251-72. Kern was Schmemann’s mentor and spiritual father at St. Sergius. Among Catholic theologians of the Liturgical Movement, the Italo-German priest Romano Guardini (d. 1968) had argued as early as 1921 that liturgical science is ultimately theology and not, as previously thought, merely a study of rubrics or of the liturgy’s historical development. ↑

See David W. Fagerberg, “The Pioneering Work of Alexander Schmemann” (Chapter 3) in Theologia Prima: What Is Liturgical Theology? Second Edition (Chicago: Hillenbrand Books, 2004). ↑

Schmemann, Introduction to Liturgical Theology, trans. Asheleigh E. Moorhouse (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1966), 14. ↑

Schmemann, “Liturgical Theology, Theology of Liturgy, and Liturgical Reform,” in Liturgy and Tradition: Theological Reflections of Alexander Schmemann, ed. Thomas Fisch (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1990), 40. ↑

See, for example, the contributions from scholars of non-liturgical or low-church backgrounds in We Give Our Thanks Unto Thee: Essays in Memory of Fr. Alexander Schmemann, ed. Porter C. Taylor (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2019). ↑

Thomas Hopko, “Two ‘Nos’ and One ‘Yes,’” St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 28, no. 1 (1984): 45-48, at 46. ↑

- Richard John Neuhaus, “Alexander Schmemann: A Man in Full,” First Things 109 (2001): 57-63, at 57. ↑

The problem with secularism, as Schmemann sees it, is that it has stolen what rightly belonged to God through claiming the natural world as its own and then circumscribing the spiritual life to a small subset of our experience. His book, For the Life of the World (first published in 1963), is an invitation to recover this holistic vision of the world as opposed to “a disincarnate and dualistic ‘spirituality’” that characterizes modern Christianity (p. 8). This and subsequent references are to the second, revised and expanded edition: For the Life of the World: Sacraments and Orthodoxy (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1973). ↑

- Robert Slesinski, “Alexander Schmemann on the Divine Liturgy as an Epiphany of the Kingdom: A Liturgical Apriori,” Communio: International Catholic Review 34, no. 1 (2007): 76-82, at 77. ↑

Schmemann, Journals, 9. ↑

Ibid., 19. ↑

- Schmemann, Of Water and the Spirit (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1974), 12. He repeats this in several other works. ↑

https://www.svots.edu/blog/copernican-revolution-liturgical-theology (accessed June 10, 2021). ↑

Schmemann, The Eucharist: Sacrament of the Kingdom, trans. Paul Kachur (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1988), 40. ↑

Ibid., 27. ↑

See Nicholas Afanasiev (d. 1966), The Church of the Holy Spirit, ed. Michael Plekon, trans. Vitaly Permiakov (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2007). The recovery of eucharistic ecclesiology in the West is at one with the name of Henri de Lubac, SJ (later Cardinal; d. 1991), who memorably said, “the Eucharist builds the Church, and the Church makes the Eucharist.” The Splendor of the Church, trans. Michael Mason (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1986), 134. Here is another example of the ecumenical cross-pollination between Catholic ressourcement and Orthodox theology in its post-1917 émigré period. ↑

Eucharistic controversy, particularly surrounding the views of Berengar of Tours (d. 1088), played a crucial role in the shift. The underlying problem, says Schmemann, is a false opposition in post-patristic theology between the “symbolic” and the “real.” The Fathers knew no such distinction; for them, the symbol (mysterion) manifests and communicates what is manifested. See “Sacrament and Symbol” (Appendix 2) in For the Life of the World; also The Eucharist, 38. ↑

Schmemann, The Eucharist, 12. ↑

Schmemann, Introduction to Liturgical Theology, 99. ↑

Schmemann, Journals, 310. ↑

Schmemann’s image of clericalism is the priest as “a ‘master of all sacrality’ separated from the faithful, dispensing grace as he sees fit” (Journals, 311). This separation, he notes, accounts for the opposition by some clergy to frequent reception of Holy Communion by the laity. See also For the Life of the World, 92-93. ↑

Schmemann, Journals, 311. ↑

Fisch (ed.), Liturgy and Tradition, 46. ↑

Schmemann, For the Life of the World, 29-30. ↑

Schmemann, Of Water and the Spirit, 11. ↑

Fisch (ed.), Liturgy and Tradition, 29. ↑

Schmemann, Introduction to Liturgical Theology, 56. ↑

Ibid., 57. ↑

Schmemann, Church, World, Mission: Reflections on Orthodoxy in the West (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1979), 214-15. ↑

Slesinski, “Alexander Schmemann,” 76-77. ↑

Schmemann, For the Life of the World, 18. ↑