The previous post described the manner of walking, kneeling, genuflecting, and bowing according to the traditional practice of the Roman rite (General Instruction of the Roman Missal (GIRM) 42). This post addresses the different postures and gestures of the hands of the celebrant. In either case, such postures and gestures are meant to be exterior manifestations of an interior disposition of prayer during the course of the liturgy. When done devoutly in a recollected way, they deepen the experience of prayer both for the celebrant and those joining him in offering the Eucharistic sacrifice.

The Manner of Holding the Hands

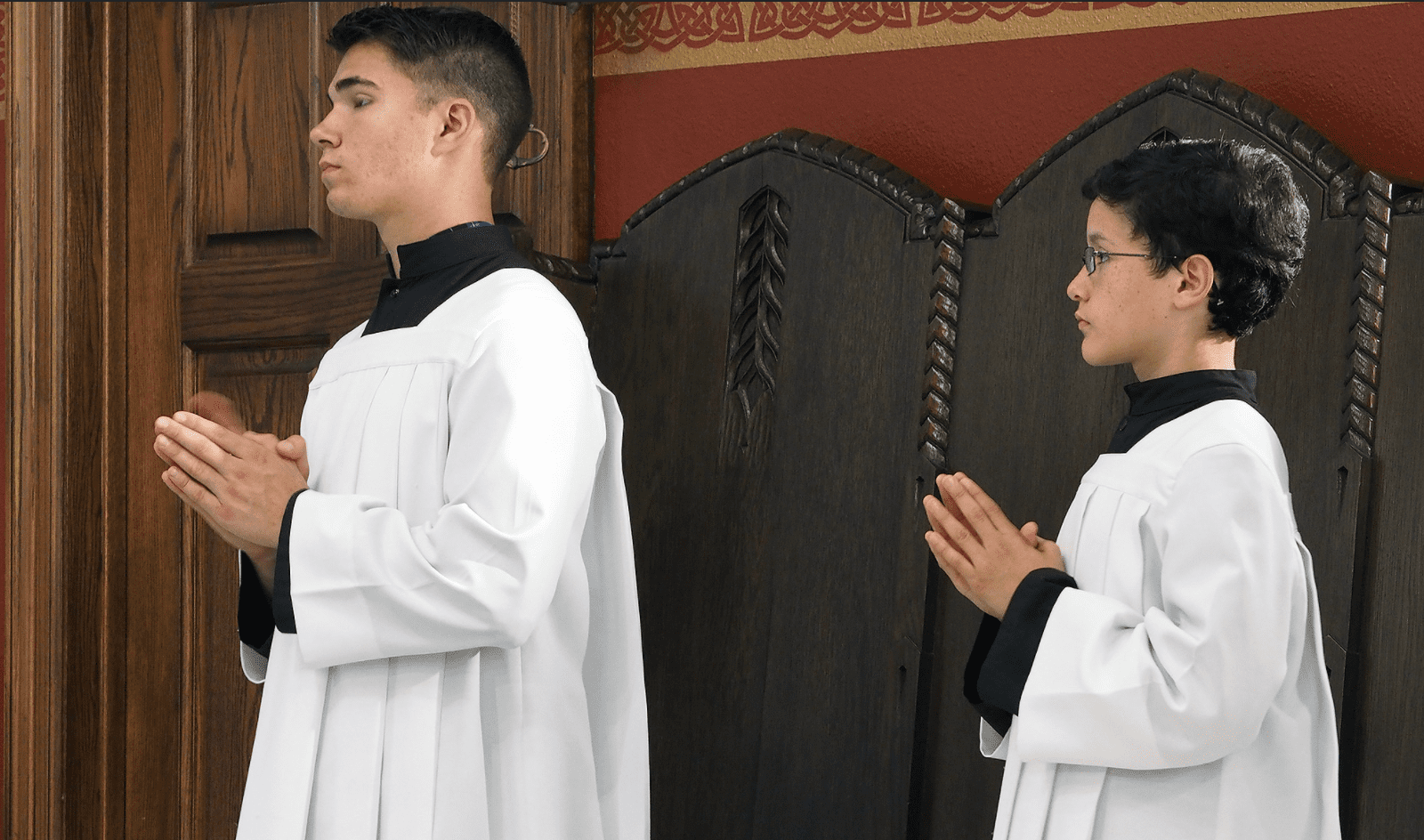

Hands joined means that the hands are held palm open, flat against each other, with fingers joined and the right thumb resting over the left thumb (Ceremonial of Bishops, 107n80). The hands are held this way whenever standing, walking, or kneeling during liturgical celebrations. The hands are held joined before the breast, with the upper arms hanging vertically from the shoulders, and the elbows resting lightly against the torso above the hips. The forearms are raised slightly to the wrist and the hands are raised slightly. The hands are kept joined even when making the genuflection or when bowing. The arms are not lowered when bowing profoundly. Likewise, the hands remain joined when going from standing to kneeling and when rising from kneeling. (It is wise, before rising, to use the right hand to free the heels from the bottom of the cassock or the alb.)

When seated, the open palms of the hand are placed on either knee with the fingers fully extended and joined. When wearing vestments in the sanctuary, one never crosses one’s arms or one’s legs or feet, nor should the hands be placed under the dalmatic or the chasuble (Mutel and Freeman, Cérémonial de la sainte messe, 43). When standing at the altar, when blessing with the right hand, the left hand rests on the altar. When standing elsewhere, when blessing with the right hand, the left hand rests on the chest (Ceremonial of Bishops,108). Similarly, when standing at the altar and using the left hand to turn the pages of the Missal, for example, the right hand rests on the altar.

Making the Sign of the Cross on Oneself

The hands are joined before and after making the Sign of the Cross. When making the sign of the Cross, the left hand is placed on the chest. The right hand, with the palm open and the fingers extended and joined, begins by touching the forehead with the right hand before the face. Then one draws a vertical line with the right hand from the forehead to a point above where the left hand is held. Then, one makes a horizontal line from the left should to the right shoulder before joining the hands once again (Mutel and Freeman, 44). One signs oneself with the Cross when standing or kneeling. Both hands are joined before and after signing oneself with the Cross (Mutel and Freeman, 44).

Imparting a Blessing

When blessing the deacon or the faithful at the end of Mass, for example, the celebrant first joins his hands and then raises his right hand to the height of his face. The fingers of the right hand are fully extended and joined, and pointed upwards. The palm of the right hand faces left and the little finger of the right hand is closest to the person(s) being blessed. The celebrant lowers the right hand vertically to the level of his chest and then raises the hand to the level of his shoulders to trace a second horizontal line from his left to his right. In general, the celebrant limits the gesture of blessing to the same points of his body as when he makes the sign of the cross on himself. He then joins the hands together once again (Mutel and Freeman, 179; Elliott, Ceremonies of the Modern Roman Rite, 71-72).

When blessing an object, the celebrant directs the gesture over the object being blessed. The palm of the right hand still faces left. The little finger of the right hand is closest to the object being blessed. The celebrant begins by tracing a line over the object, beginning at a point at a distance from himself and drawing the hand toward himself in the same horizontal plane. The celebrant returns the right hand along the same horizontal line to a position immediately over the object being blessed. Then the hand draws a line from left to right over the object, always remaining in the same horizontal plane. The celebrant draws his right hand directly over the object and then joins both hands once again (Mutel and Freeman, 73-74).

Signing Oneself at the Gospel

The hands are joined before the breast. The deacon or the priest who proclaims the Gospel first traces a Greek cross at the first word of the text with the thumb of the right hand, the left hand resting on the Gospel book. Then with the left hand resting on the chest, he raises the right hand, fully extended with fingers together, and separates the thumb from the rest of the hand. Holding the hand parallel to the face, he traces a Greek cross with the right thumb on the forehead, the lips, and over the heart (customarily over the left breast) before joining the hands once again (Mutel and Freeman, 44). It is best to avoid making the sign of the cross on the lips while one is speaking.

Taking Holy Water

At the door of the church or of the sacristy, one takes holy water from the stoop by dipping the index and middle finger of the right hand, the left hand resting on the chest. If two persons are walking side by side in procession, the one closest to the stoup, before signing himself, presents these same two fingers to his companion who touches them with his index and third finger of the right hand to receive the Holy Water (Mutel and Freeman, 76). Both then sign themselves as indicated above.

Striking the Breast

Both hands are joined. Then the left hand is placed below the breast. With the right elbow near the body, the right forearm swings slightly away from the body before being drawn toward the chest. One strikes the chest with the open palm of the right hand, fingers extended and joined. Then one joins both hands (Mutel and Freeman, 45). When striking the breast at the altar, as during “To us, also, your servants…” during Eucharistic Prayer I, the left hand rests on the corporal, not on the chest (Mutel and Freeman, 142).

Conclusion

This concludes the summary of postures and gestures of the Mass in the Ordinary Form according to the traditional practice of the Roman rite. These brief descriptions are offered to priests, deacons, seminarians, and all those responsible for the careful preparation and execution of parish liturgies and the training of the Church’s liturgical ministers. In offering the indications described in these posts, this author has hoped that the beauty and grace of the Church’s liturgical celebrations inspire more and more men and women to seek with their whole heart the One who is Beauty itself. The next, and final, post will offer a few last notes on why these traditional actions will only serve to beautify and deepen celebrations of today’s Mass for years to come.