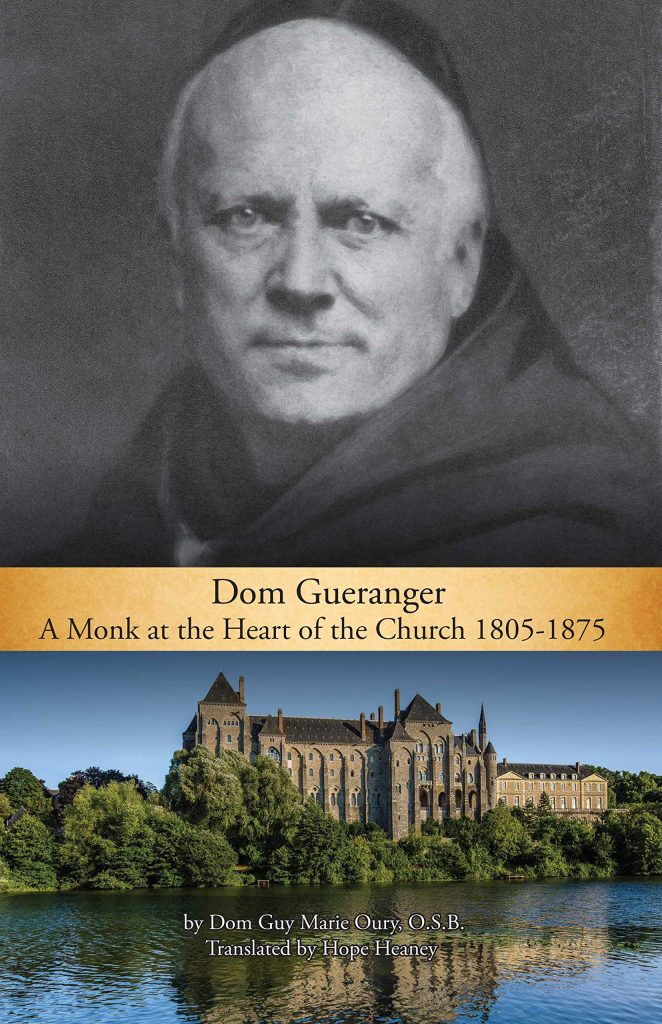

Dom Gueranger: A Monk at the Heart of the Church by Dom Guy Marie Oury, OSB (trans. By Hope Heaney), Fitzwilliam, NH: Loreto Publications, 2020. 526 pp. ISBN: 978-1622921522. $29.95.

Dom Guy Marie Oury’s Dom Gueranger: A Monk at the Heart of the Church is not a perfect book, but it is an important book, if only because it offers our dying culture a road map to recovery.

I say “dying culture.” It should come as a surprise to no one that our culture—and Western Civilization as a whole—is dying. I say this not as a matter of pessimism. Nor am I discounting divine intervention. But there are symptoms enough to show that our culture is very much like the “patient etherized upon a table” in T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.”

What are the symptoms that our patient is dying? We could point to particulars: the broad-scale acceptance of abortion; declining birthrates in most Western countries; the destruction of the family through permissive divorce laws and so-called “same-sex” marriage; and most recently, society’s pandemic confusion over natural gender and the complementarity of the sexes.

As Catholics, believing as we do that God continues to work in and through the world, we cannot simply throw up our hands or throw in the towel. But how do we begin to regenerate a culture so seemingly hopeless? The answer is right before our eyes—and present to our other senses as well—in the sacred liturgy. Benedictine Father Cassian Folsom understands this better than most, having formed an effective Catholic counterculture with his fellow monks at the Benedictine Monastery of Nursia in Italy. As Father Folsom notes in a 2018 presentation at the Avila Institute (and reprinted in the May 2019 issue of Adoremus), liturgy plays an essential role in culture.

“Culture always comes from the worship of something, the veneration of what we care most deeply about,” he says. “In Western civilization, a glorious culture of extraordinary beauty developed from the worship of God in the Catholic liturgy, in particular in the sacrifice of the Mass. Since that culture has gradually and progressively separated itself from its origins in the Catholic cultus, it is no longer sustainable. In many places in Europe, splendid cathedrals which once throbbed with life are now reduced to museums: empty shells of a past no longer understood, no longer loved—indeed, a past that is sometimes hated.”

Father Folsom adds that, while modern culture still has its gods to worship, they are, if we may judge them by their fruits, death-dealing gods, which require a corrective or a “shock to the system.” That shock is found in the liturgically structured life of the Benedictine community. And now, with Dom Oury’s Dom Gueranger available in English (it was originally published in French in 2000), we have another Benedictine’s word for it.

Cultured Approach

Dom Prosper Gueranger was one of the greatest Churchmen of the 19th century and a case study in how to provide the necessary “shock” to recapture the mystery of the Christian faith. Consider: he founded the first Benedictine community in post-revolutionary France in 1836, now known as St. Peter’s Abbey, at the priory of Solesmes after it was abandoned during the French Revolution. Gueranger also restored Gregorian chant within the Church, culminating in the Second Vatican Council’s pronouncement that it deserves “pride of place” in all liturgies (Sacrosanctum Concilium, 116); and he renewed a love for and knowledge of the Roman liturgy in France—leading his successors to spread that same love and knowledge throughout the rest of the Western world.

In the preface to Dom Gueranger, Dom Philip Anderson, abbot of Clear Creek Monastery in Oklahoma (which claims its roots in Solesmes), sums up Gueranger’s life and contributions succinctly: “The abbot of Solesmes was a man of a great and single idea. He had from the start the genial intuition of his mission, and he devoted himself entirely to it: that of restoring to our disinherited age all the scattered treasures of the thousand-year tradition of Christianity, and above all the forgotten riches of antiquity that the Church preserves in her liturgy.”

Abbot Philip also recounts the great abbot’s particular accomplishments regarding the liturgy. “Many Catholics know Dom Guéranger as the author of The Liturgical Year, a guide to the Church’s liturgy that has helped them understand and appreciate the riches of the Roman Catholic liturgy. Many have also heard of the work accomplished by his monks at the Solesmes abbey in France for the restoration of Gregorian chant.” He adds that “this incomparable liturgist was also a saintly monk, whose cause of beatification has begun [in 2005] in the Diocese of Le Mans, France, where he lived and died. He is now given the title of ‘Servant of God.’”

In addition, Abbot Philip notes, Gueranger “was the friend of saints and of popes. Pope Blessed Pius IX…wrote, along with many other high praises of Dom Gueranger, the following words: [‘]By his virtue, piety, zeal, knowledge, and by the work of a lifetime, he showed himself to be a true disciple of Saint Benedict and a perfect monk.[’]” The dynamic Benedictine father of Solesmes had also “contributed written works ‘full of faith and sacred learning’ that served to uphold the Holy See in making…ex cathedra pronouncements” defining the Immaculate Conception in 1854 and Papal Infallibility in 1870.

And yet, except within liturgical circles, it seems that knowledge of Gueranger’s accomplishments is often eclipsed by other equally important figures in the Church at the time, including most notably his contemporary across the Channel, Cardinal John Henry Newman (whom, as Oury relates, Gueranger met during a visit which was both brief and awkward as the Churchmen were stymied by a language barrier—Newman knew little French and Gueranger less English).

So it is that Dom Oury has done a great service in providing a meticulously researched and wide-ranging biography of Dom Gueranger. In doing so, he also provides the Catholic reader with a working account of how to restore culture—beginning, as Father Folsom notes, with a keen focus on the liturgy.

Old: the New New

If we consider the secular forces at work in France—and they were legion—after the bloody revolution had decimated the faith in that country, it is clear why Gueranger saw the liturgy as the best possible antidote to the moribund state of the French Church and the liberal waywardness of French society. Oury cites Gueranger writing in his autobiography that the liturgy transcends any particular culture both in its mystery and in its history: “Liturgy is the language of the Church, the expression of its faith, its vows, its tributes to God: thus, antiquity must be chief among its main characteristics. Any liturgy that comes into being having nothing to do with the liturgy of our fathers is unworthy of the name…. A civilization does not achieve seventeen centuries of existence without a sufficient language to express its thought….”

For Gueranger, the liturgy was not merely what one did on Sundays; rather, it was the clearest and most powerful way that the faithful could achieve sanctity and make manifest to the rest of the world the four marks of the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church. “Starting with the current state of the liturgy,” Oury writes, “Dom Gueranger planted the ideas of unity and a return to unity among the primary objectives of his teachings and his battle [with secular French society and a compromised French Church]. Beyond these objectives, he formed a theology of the Church and a theology of the liturgy…. Dom Gueranger considered the liturgy as the primary visible manifestation of the Church and of its true nature; in a way, it could be said that the liturgy was the basis for the life of the Mystical Body.”

But if liturgy was the lodestar by which Gueranger sought to renew the faith of France—and the world—he also saw the liturgy necessarily within the context of a society in but not of the world—the Benedictine ideal. “One key notion held by Dom Gueranger,” Oury writes, “which he repeated constantly as the basis for his thinking and the source of his other teachings, was that the essence of monastic life did not differ from Christian life. Monastic life was a Christian life in its fullest state of perfection, lived in accordance with every demand.”

The liturgy was not simply reserved, in other words, for the spires and clerestory of monasticism but was to transform all members of society—from the inhabitants of the rudest cottage to the denizens of the most regal castle. “In Dom Gueranger’s mind,” Oury writes, “Christian life as a whole had a liturgical and sacerdotal character, both participation and pre-figuration of the eternal liturgy…. Liturgical assemblies on earth were the reflection and imitation of the heavenly liturgy eternally celebrated by angels and saints; liturgical assemblies were a communion with the heavenly liturgy.”

The importance of culture remained a keystone for Gueranger’s teachings on the liturgy; it was not to exist in a vacuum, nor was it to be condemned as an outdated and esoteric practice with no real-world application. As Oury notes, “Father Gueranger heralded the advent of a new type of post-Christian society: ‘Another era is approaching, one that is faithless and indifferent to truth and error….’ But he remained convinced that the permanent confusion of minds would never be the norm. ‘I have no doubt that one day Catholicism will return to its place in this world, to which it alone holds the secret.’”

St. Cecilia at Solesmes

While Gueranger did not live long enough to see his plans come to full fruition, he did accomplish a few momentous steps toward realizing a world newly enamored with and informed by the liturgy. One of these steps was the Abbey of St. Cecilia in Solesmes, a monastery for Benedictine nuns, which he founded nine years before his death. Named for the third-century martyr to whom Gueranger had an ardent personal devotion (not surprisingly, since she is the patron saint of music), the abbey was formed on the same model he used for his monks at Solesmes. According to Oury, St. Cecilia’s served as a great comfort in Gueranger’s declining years, but it also served as an opportunity to further spread his ideas about the liturgy.

“The work of the foundation and the training at Sainte-Cecile had taken precedence over the abbot of Solesmes’ other tasks, ones he had started or planned,” Oury writes. “At the same time, Sainte-Cecile forced him to clarify his thoughts and apply his monastic ideas. He had before him a breeding ground that was particularly receptive to his ideas.”

Throughout his struggle to gain support for the Roman liturgy in a country still in the throes of Gallicanism and habituated to the Gallican Rite, Gueranger always sought supra-legal means to reintroduce the Roman Rite into France.

“I tried to express my feelings of respect and affection for the Roman liturgy,” Gueranger states, quoted by Oury, “and I set forth the need for the liturgy to be ancient, universal, sanctioned, and pious—principles that were in direct conflict with the French liturgies. I did not attack the abuse from a legal perspective; it seemed all too obvious to me that Rome had yielded on that point. But I laid siege to obstructing the French position and by compromising the disastrous Gallican liturgy in a simple comparison between it and the foundations of the Catholic institution.”

Thus, with St. Cecilia’s, Gueranger found a perfect second laboratory for his ideas about the liturgy—a laboratory full of women devoted to Christ their bridegroom whom he hoped would help his monks foster a love for the liturgy throughout French society. Both St. Cecilia and the monastery she patronized embodied Gueranger’s view of the liturgy as a force for good in secular society. “The establishment of Christianity in Rome, the first generations, and the developing influence of the apostolic See over the entire Church were subjects that had impassioned Dom Gueranger since his youth,” Oury writes. St. Cecilia figured largely in Gueranger’s fascination for the early Church; in fact, he had written a biography of the saint, and he saw her as an avatar of his ideas.

Indeed, Gueranger’s ideas and achievements regarding the liturgy at both St. Peter’s and St. Cecilia’s were embodied by this third-century martyr. “The church for [St. Cecilia’s],” Gueranger writes, quoted by Oury, “whose arches resound with nothing but the ancient and sweet Gregorian melody, is a powerful draw to the heart and eyes of the pilgrim. We feel that Cecilia truly chose […] this sight as one of her dwellings.”

Revise and Renew

It is hoped that the wealth of resources which Dom Oury provides in his book will help introduce Dom Prosper Gueranger to the wider English-speaking world. It is also hoped, however, that with a second printing, the editors at Loreto Publishing will correct the great many editorial flaws within the text itself. For example, the text notes that the author of a pamphlet addressing the fate of the Papal States was “correcting the the proofs himself” [sic]. Alas, that the publisher and editor of the Oury translation did not take such pains in their own work! In fact, there seems to be a double irony here—magnified by the great number of editorial flubs—that a publishing house should overlook such editorial details in a work on the life of Gueranger, whose lifework was to ensure that every detail of the liturgy was correct and correctly understood.

Likewise, in a future edition of the book, the editors ought to consider employing footnotes to provide a greater sense of the various contexts in which Gueranger lived and operated. Oury presupposes a working knowledge of post-revolution France, especially in the years which chronicle Gueranger’s life (1805-1875). The major events and figures of this period are touched on but inadequately explained for those unfamiliar with French history during this period. Footnotes would go far to help the reader better understand, for example, references to Gallicanism, Ultramonatism, and Jansenism and to such figures as Robert Lamennais, Charles Montalembert, and Jean-Baptiste Lacordaire, all of whom played an important role in Gueranger’s life.

Editorial issues aside, however, Dom Gueranger: A Monk at the Heart of the Church provides a fully drawn (if imperfect) portrait of the man who had almost singlehandedly renewed the liturgy as the cultural heart of the Church. It also provides a living example of how Catholics can save civilization, one celebration of the Holy Mass at a time.