The longsuffering Job, like so many figures in the Old Testament, is a prefigurement of Jesus. The fourth-century St. Zeno of Verona makes this connection: “As Job sat on a dunghill of worms, so all the evil of the world is really a dunghill which became the Lord’s dwelling place, while men that abound in every sort of crime and base desire are really worms” (see the Office of Readings for Saturday of the Eighth Week in Ordinary Time). The Holy Triduum recounts how Jesus—“a worm, and no man” (Psalm 22:6)—saved this dunghill of a world by suffering and dying, before rising—and ascending.

The Ascension of Jesus into heaven, celebrated 40 days after his Resurrection (or, in many places, on the Seventh Sunday of the Easter Season), completes his Paschal Mystery. Perhaps its relative distance from the Resurrection, at least when compared to Holy Thursday and Good Friday, accounts for it being in many minds a sort of afterthought. Even those who try to live by the liturgy and its mysteries find the life-giving Triduum waning in the first weeks after Easter. In my personal experience, in fact, Lent’s 40 days before Easter certainly seem more significant in my spiritual life and that of my family and parish than do Easter’s 40 days before the Ascension.

This is too bad: Lent recalls our fall and plods through the dunghill of this world, while the Easter season celebrates the divine life—and the divinization it brings—as it gives us a foretaste of heaven (as Father Christiaan Kappas notes in his article on the Ascension of Jesus on page 5).

In addition to the place of the Ascension in our spiritual lives, the Ascension also seems to speak to this current post-COVID situation (at least we hope it’s post-Covid) for liturgical celebrations. For what seems a long time now, our liturgies—every sacramental celebration, in fact—have been adapted to meet the demands of health and safety. Some adaptations have been small, others great; some prudent, others not; some licit, others invalid. Hindsight is 20/20, and each bishop, priest, and layman can look at the past months and judge for himself how well or poorly particular liturgies have glorified God and saved souls. But rather than focusing too exclusively on the past (there are, of course, liturgical lessons to be learned), clearer vision will also look ahead—or, inspired by the Ascension, look up.

Anyone familiar with the Second Vatican Council’s document on the liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, and its preceding liturgical movement knows that “active participation” in the sacred liturgy is the source of the “true Christian spirit” that will transform the fallen world unto God, as Pius X wrote in his 1903 document, Tra le Sollecitudini. But fewer recall the Holy Father’s subsequent stern warning about profaning the household of God and abusing the great gift which is the Church’s liturgy. He gets right to the point: “it is vain to hope that the blessing of heaven will descend abundantly upon us, when our homage to the Most High, instead of ascending in the odor of sweetness, puts into the hand of the Lord the scourges wherewith of old the Divine Redeemer drove the unworthy profaners from the Temple” (see Tra le Sollecitudini, emphasis added).

While our recent liturgies, beset with an extra dose of the world’s fallen effects, have required adaptations, the time is coming when we will need to get back to the books. Are we looking ahead—looking up—and planning to restore the Mass and sacraments to the glory they are meant to have—honoring God with the “ascending odor of sweetness”? Or will we be satisfied with liturgical minimalism, sacramental aberrations, and anemic participation—placing “scourges in the hand of the Lord,” as it were?

The road between Ash Wednesday and the Ascension is tiresome and deadly—but also life-giving and heavenly. Our world may seem like Job’s “dunghill of worms,” but it has been redeemed and made new by Christ risen and ascended. The lesson for our liturgies follows a similar trajectory: from the ashes and dust of a fallen world, we work (or, rather, we assist God in working) to celebrate and participate in the liturgy of heaven. We’ve looked down too long. It’s time that the world asked us at Mass, like the men of Galilee: “Why are you standing there looking at the sky?” (Acts 1:11).

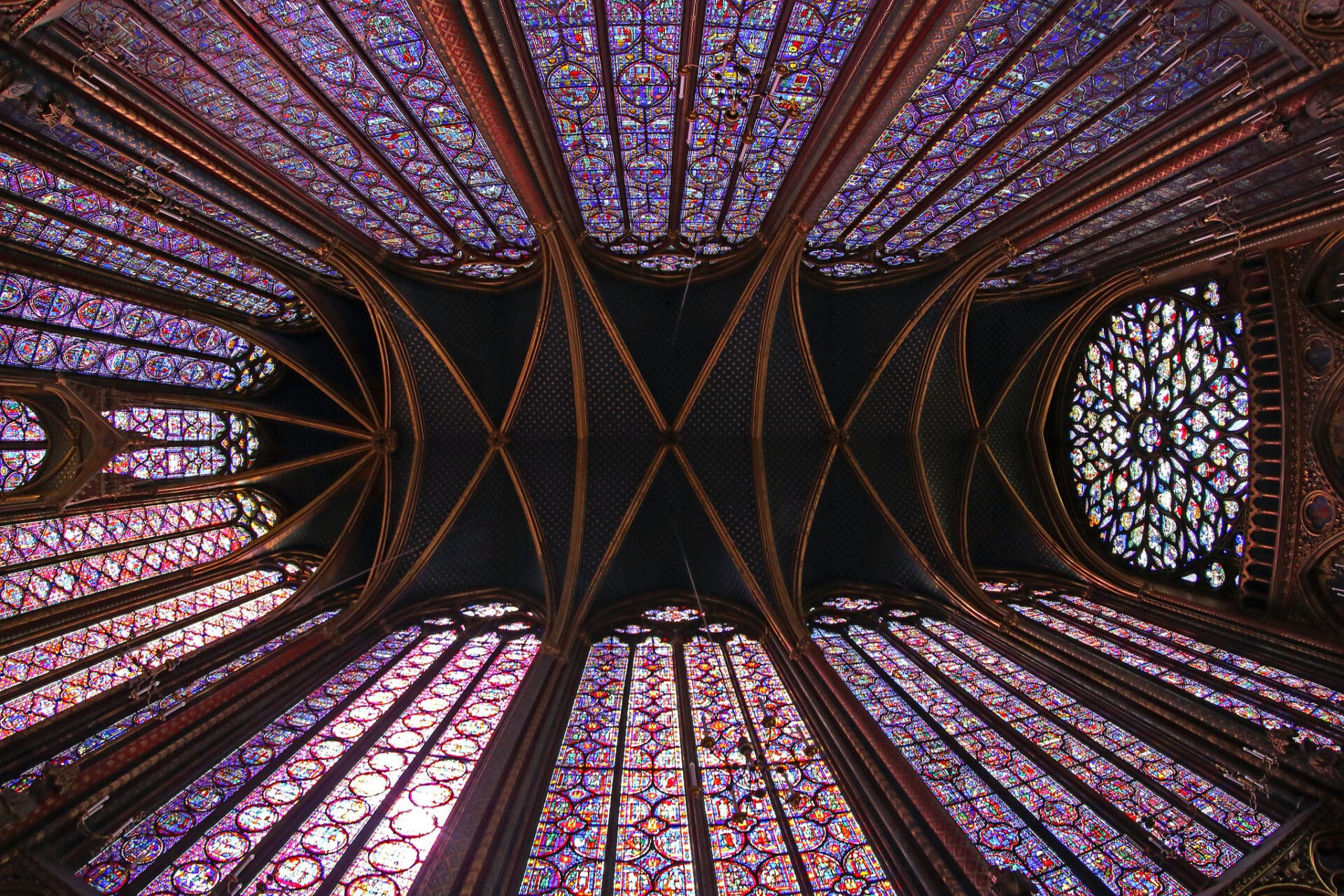

Our response as Catholics should reflect not that we have our heads in the clouds, lost in abstractions and anxieties, but that we are waiting with joyful gaze for the coming of the Lord again in glory. We may be, as the trite saying goes, “an Easter people,” but we are also “an Ascension people,” rising with Christ to the Heavenly Jerusalem—not only joyous in anticipation but also celebrating the joy of Christ’s heavenly glory, here and now.