By now most of us are surfeited with the canard that the Church must embrace “simple” liturgical language and ceremonies, architecture, and artwork if it is to “speak to ordinary people.” But the unqualified “simple” is more often than not merely a euphemism for bland, banal, immature, casual, and intellectually vacuous.

Rather, we know that elevated language, ritual formality, and high art exert important formative influences over those habitually exposed to them, and that receptivity to these qualities is inherent in human nature rather than the preserve of a cultured elite. I would expect, however, that relatively few of those familiar with such points are also aware that the development and spread of Baroque art, one of history’s most sophisticated and allegedly elitist artistic styles, was largely grounded in the Church’s desire to bring its message to the poorest and least-educated segments of society. In fact, as historical evidence bears out, the Church succeeded in that mission.

A Tuscan Landscape

As the Council of Trent began, artistic life in much of Italy was dominated by the influence of the Tuscan School. Founded by Brunelleschi (d.1446), Donatello (d.1466), and Masaccio (d.1428), perfected by Leonardo da Vinci (d.1519), Michelangelo (d.1564), and Raphael (d.1520), the Tuscan School is often and erroneously treated as virtually equivalent to the Renaissance. This is partly because it constituted a sharper break with the immediate Medieval past than did other artistic schools of the era. Most variants within the Renaissance actually attempted a synthesis of medieval aesthetics with aspects of the rediscovered art and artistic techniques of ancient Greece and Rome. The Tuscan School, in contrast, rejected the artistic heritage of the Middle Ages in favor of rigid conformity to the principles of Greco-Roman classicism. Its approach was then adopted by such arbiters of taste as the first major historian of art, Giorgio Varasi (d.1574); founder and first president of Britain’s Royal Academy of Art, Sir Joshua Reynolds (d.1792); and the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (later the Academy of Fine Arts).

From the perspective of the topic under discussion, the most notable quality of Tuscan art was its attempt to embody what the canons of strict classicism considered ideal beauty—even at the expense of naturalistic depictions of the world as we know it. The best and most famous representatives of the Tuscan School did, it is true, attempt to combine classicism and naturalism through the depiction of real life scenes closely approaching to classical ideals, but it was classicism that was treated as essential, naturalism as ultimately negotiable. Some artists of the Tuscan School (most notably Raphael) even depicted human beings based upon “ideal” proportions of the human body rather than the appearance of live models. True genius largely overcame the impediments such presuppositions placed in the way of artistic success. In the hands of the lesser disciplines and imitators of the great Tuscan artists, it often resulted in works that maintained the weaknesses of those by the masters while lacking their strengths. Human figures placed in grotesque postures and including even more grotesquely bulging muscles (sometimes found in the work of Michelangelo) became particularly popular.

A particularly important aspect of this classicism is that it aimed not just at work of the highest aesthetic caliber but also at work aimed at those educated in and committed to a certain aesthetic philosophy. When this resulted merely in a “classical” arrangement of the figures and objects and colors in, say, a scene of Christ’s birth, it presented no problem to an “ordinary person’s” ability to understand the subject and the meaning of a work of art while those persuaded by classicist aesthetic theories also found added grounds for appreciation. But there was also a tendency, particularly among Tuscan School artists of the second rank, to create scenes with no particular meaning to an ordinary person and whose purpose was merely to embody such classicist notions as proportion and symmetry while showing off the technical virtuosity of the artist.

Commitment to Reality

In contrast to the Tuscan School, the Venetian, Flemish, and Dutch Renaissance schools were more committed to naturalistic depiction of the beauty of the real world. These schools adopted much from the Greeks and Romans because of the undoubtedly high quality of their artistic achievements and because of the excellence and practical value of their techniques—not because they constituted a standard of perfection to be adhered to in all its principles and details. Classicism for its own sake might (or might not) sometimes be incorporated into their works but only to the extent that it did not detract from naturalism. And it was to these schools that the authentic Catholic reform movements of the mid- to late-16th-century Church largely turned for the creation of art that would be as “elite” as any in the aesthetic standards it attained, but whose naturalism would allow it to easily communicate stories from the Bible, Church history, and the lives of the saints to all segments of the populace.

This turn to naturalism received a special impetus from the Society of Jesus—whose emphasis on the use of visual imagination in meditation stood contrasted with some other methods and whose impact on the whole of life in the second half of the 16th century was considerably broader than most people today are likely to suppose. On the one hand, Jesuit efforts to enlist the elite segments of society in the mission of the Church led them into close and influential relationships with creators and arbiters of high culture. On the other hand, they were able to capture the popular imagination through the processions and other large-scale devotional exercises which they (and those influenced by them) organized, and which became major public events in a society that took the truth of Christianity for granted and lacked the popular entertainment of the present day. Even the less than devout, in the manner of some of Chaucer’s pilgrims, joined in an activity which provided a rare diversion from the routine of life. Thanks to these multifarious activities, the Jesuits attained a wide and subliminal influence over people’s minds that can in some ways be compared to that exercised today by televisions, movies, and popular music.

Of particular importance to the current topic is the aspect of traditional Jesuit meditation known as “composition of place.” The person meditating chooses a particular historical, symbolic, hypothetical, or future scene—stories from the Gospels or mysteries of the rosary for example—and imagines himself living through the scene, creating as realistic a mental impression as possible of its exact sights, sounds, smells, and so on. This then leads into reflections upon the moral messages the scene can convey, resolutions about our future conduct and prayers of adoration, atonement, thanksgiving, and petition. In areas under strong Jesuit influence, this creation of realistic, vivid images could become instilled in people as a normal part of life even if they were not particularly devout. Not only were the laity instructed in composition of place, but some of the only artwork most people would ever see was painted with the Jesuit approach to meditation in mind. Outdoor religious plays aimed at the same type of realistic visual depiction and were among the most widely watched dramatic performances.

The Other Michelangelo

It was in just such an atmosphere that one of the founding geniuses of the Baroque spent his childhood and his artistic apprenticeship.

When Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (not to be confused with Michelangelo Buonarroti) was born in Milan on the 29th day of September in 1571, St. Charles Borromeo had been the city’s archbishop for seven years and would remain so for another 13. Constanza Colonna, who later became one of the artist’s most important personal patrons, was waiting for news of her father—then one of Don John of Austria’s chief subordinates in the fleet that would soon win the Battle of Lepanto. Her brother was married to Borromeo’s sister. Her husband was a marquis who worked professionally with Caravaggio’s maternal grandfather and likely employed the future artist’s father. If that was not enough to put Caravaggio into a milieu close to the heart of Catholic reform, one additional detail of his family certainly would: one of his own brothers became a Jesuit.

During Caravaggio’s formative years, the Archdiocese of Milan was in the middle of a wide-ranging reform largely grounded in the spirituality of the Jesuits, under whose influence Borromeo’s own life had been transformed. As a reforming archbishop he emphatically believed that ecclesial art ought to aid the meditations of the common people. As a member of one of Italy’s oldest aristocratic families, he had been educated to appreciate the artistic excellence he knew could be put at the disposal of his apostolic purposes. His efforts included publication of a book on ecclesiastical art and insistence upon strict adherence to its principles in the churches of his archdiocese. The works created upon these principles not only contributed to the intended spiritual renewal but also had a real impact on the broader development of artistic style in the region. Because the Church was a lead employer of artists, those in Milan would have fallen under Borromeo’s guidance—the stylistic developments they embraced to obtain commissions for ecclesial art in time influencing their secular works. The archbishop’s personal relationships with some of Milan’s most important secular artistic patrons served to enhance this tendency.

Faithful Art

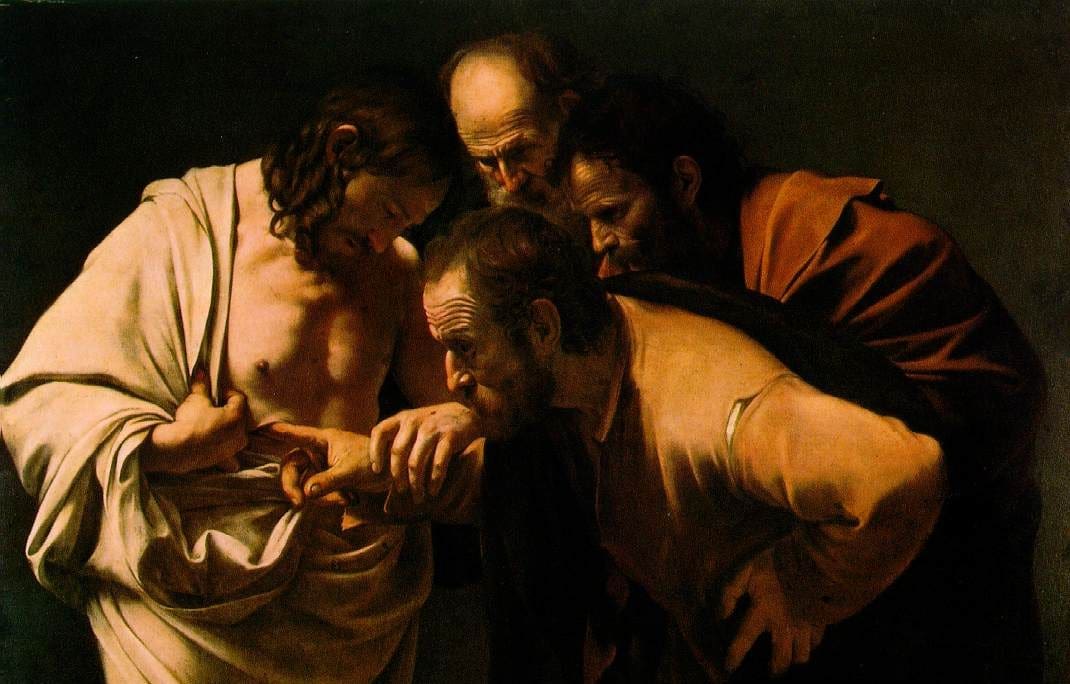

The Milanese master under whom Caravaggio served as an apprentice, Simone Peterzano, in some ways exemplified the synthesis of Venetian and Jesuit influences. Peterzano professed himself a follower of Titian (d.1576), the greatest of the Venetians, and was also an admirer of that artist’s two closest rivals, Tintoretto and Veronese. His tendencies towards Mannerism (a sort of superficial, at times even caricatured, imitation of the styles of earlier Renaissance artists) were largely overcome by his need to conform with St. Charles Borromeo’s requirements. Caravaggio was not only to rise far above the minor painter under whom he studied but to produce works equaled by only a fraction of those of the Venetian masters. Among his key accomplishments was the development of a dramatic quality that is easier understood than explained but which parallels Jesuit meditation’s focus on creating mental images of a scenes of action. Venetian work often has a sort of “static” naturalism, with the look of humans posed motionless as though for a photograph. Figures in Caravaggio’s work (and that of much subsequent Baroque art) are more likely to look as though they have been caught in a moment of motion, like the image on a screen when a DVD has been paused.

By the mid-1590s, Caravaggio was in Rome, where he established himself as the city’s preeminent living artist and where his influence was joined to that of the Carracci (the brothers Annibale and Agostino and their cousin Ludovico). These three men had already been initiating developments with important parallels to Caravaggio and though they never took these as far as he did—and never reached the same heights of artistic brilliance—they nevertheless played a key role in the advancement and propagation of Baroque aesthetics through their founding of an art academy. The result was a transformation of Roman art that played a role in the spiritual transformation of the city that was taking place after its descent into an abyss of corruption. This spiritual renewal was being led by the Congregation of the Oratory, whose founder, St. Philip Neri, had himself been a friend of St. Ignatius and whose methods of prayer owed much to Jesuit influence.

Aside from the rather obvious fact that it could not have played more than a subordinate role in the spiritual renewal of the Counter-Reformation, it is naturally impossible to quantify the extent of the influence exercised by ecclesial art, a difficulty exaggerated by the fact that the spread of such art was both in part a cause and in part of consequence of the revivification of Catholic life. What the historical record does demonstrate is that the least educated and least cultured segments of the population—not just in Milan and Rome—but throughout 16th-century Europe, embraced what many would now dismiss as “elitist art.” Their instinctive reaction was to find in it an aid to and an expression of religious devotion, rather than to view it as “upper class.” Some, perhaps, might have been more tepid, but negative reactions were confined to those with preexisting commitments to Protestant doctrine and to generic malcontents.

A Common Patrimony

Today we see the attitudes of the “common people” of 16th-century Europe replicated among Catholics of Third World countries. Catholic converts from rural Africa might not be able to construct Gothic cathedrals or Baroque basilicas, but they certainly try to beautify their humble churches as much as their circumstances allow, and those who are able to go to Rome are positively impressed by the beauty of its churches and the devotion which inspired them. First-world Catholics imbued with Protestant or politically leftist attitudes are the ones who find such beauty appalling. They are also the ones who tried to drag the lower classes in Latin America out of their tendencies towards elaborate devotion, with the result that the region’s people are leaving the Catholic Church for Evangelical Protestant groups whose plain approach to worship is focused on God rather than political activism.

Ironically enough, it is the opponents of ecclesial high art who prove to be the true elitists by rejecting ordinary and poor people’s instinctive love of beauty on the basis of doctrines that could only be invented by those who are both sufficiently privileged in their education and sufficiently detached from human normality to spend their time cooking up bizarre theories.