Our current Roman Missal was “Renewed by Decree of the Most Holy Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican” (front matter to the current bound Missal). And of the Second Vatican Council’s 16 documents, the first was Sacrosanctum Concilium, the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy. “It was no accident,” one commentator noted, “that the first completed work of Vatican Council II proved to be the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy…. For decades, a vigorous liturgical movement had been going on…. Thus, when the Council addressed itself to the liturgy, all the basic spadework had been done.” So, if we wish to understand as fully as possible our current Missal, then we must also read accurately the Second Vatican Council—which entails also an appreciation of the great minds of the modern liturgical movement. In this quiz on the liturgical movement, we’ll see how the Liturgical Movement can assist our reading of the Council and its Missal through what Pope Benedict XVI called “a hermeneutic of reform” and renewal. How well do you know the Liturgical Movement that helped form the Missal used each day?

Dorothy Day

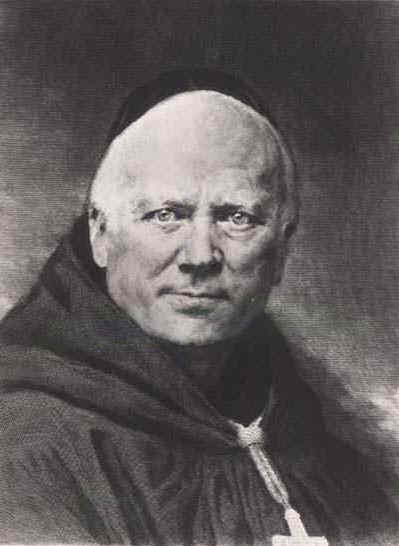

Dom Lambert Beauduin

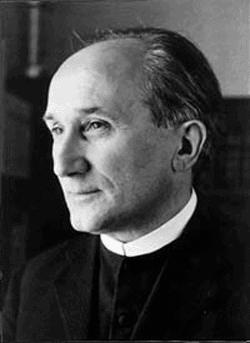

Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius X

Dom Guéranger

Romano Guardini

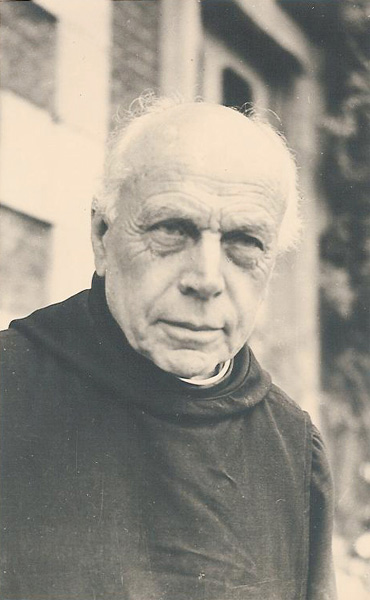

Virgil Michel

- The “Liturgical Movement,” as its name implies, desires to move or change something. What is it that the movement’s key figures wished to change?

- People’s generally unfavorable opinions about liturgists.

- The Mass.

- The people who attend liturgical services.

- Liturgical dances.

- Liturgical law and tradition.

- What event is most commonly associated with the beginning of the modern Liturgical Movement?

- Dom Prosper Guéranger’s reestablishment of the Benedictine Priory of Solesmes in 1833.

- The First Vatican Council (1869-70).

- Pius XI’s 1928 apostolic constitution, Divini Cultus, “On Divine Worship.”

- Pius XII’s 1947 encyclical, Mediator Dei.

- The Second Vatican Council (1962-1965).

- True or False: The founders of the modern liturgical movement thought it necessary to downplay the importance of the ordained priest in order to elevate the common priesthood of the faithful—and thus facilitate the latter’s “active participation.”

- Which liturgical movement figure claimed that “many years will have to pass before this type of [reformed] liturgical edifice…can appear purified of the squalidness brought by time, newly resplendent with dignity and fitting order”?

- Pope Paul VI.

- Annibale Bugnini.

- Pope Pius X.

- Louis Bouyer.

- Romano Guardini.

- Which Liturgical Movement figure did Pope Benedict XVI claim to have “perhaps the most fruitful theological idea of our century”?

- Romano Guardini.

- Pius Parsch.

- Louis Bouyer.

- Hans Urs von Balthasar.

- Odo Casel.

- On the heights above the Bavarian town of Rothenfels stands a castle. Which Liturgical Movement figure discussed liturgy, culture, and social issues with college students in this castle?

- Dietrich von Hildebrand.

- Maurus Wolter, OSB.

- Columba Marmion, OSB.

- Romano Guardini.

- Ildefons Herwegen, OSB.

- To many minds today, devotion to the liturgy and service to those in need are mutually exclusive: you can do one or the other, but not both. True or False: This perceived divorce between liturgical worship and social action finds its roots in the Liturgical Movement.

- Who wrote the first encyclical devoted entirely to the topic of the Liturgy?

- Pius X.

- Pius XI.

- Pius XII.

- John Paul II.

- Benedict XVI.

- The Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, echoing Pope Pius X, placed which as the “aim to be considered before all else” in the restoration and promotion of the sacred liturgy?

- Sacred music.

- Active participation.

- Lay ministry.

- Frequent reception of Holy Communion.

- Catechesis.

- What were some of the goals successfully achieved by the Liturgical Movement?

Readers’ Quiz Answers:

- c. The people who attend liturgical services. As the 1930 pamphlet, “The Liturgical Movement,” explains: “The word ‘movement’ is rightly understood to indicate an endeavor ‘to bring about a change.’ The false notions in this matter are due principally to a misunderstanding as to the subject of the proposed change…. [W]hat is really being striven for is a change in the spiritual orientation of the faithful…. The Liturgical Movement, therefore, as the words indicate, is a movement—a movement towards the liturgy” (Popular Liturgical Library, Series IV, No. 3, Liturgical Press in Collegeville, MN, 5). While the work of the Liturgical Movement turned its focus to ritual changes in the 1950s, the initial goals of the Movement were principally geared toward moving the people into the depths of the liturgy. Joseph Ratzinger subscribed to this same principle, as he explains in his 2000 book, The Spirit of the Liturgy: “If this book were to encourage, in a new way, something like a ‘liturgical movement’, a movement toward the liturgy and toward the right way of celebrating the liturgy, inwardly and outwardly, then the intention that inspired its writing would be richly fulfilled” (8-9).

- a. Dom Prosper Guéranger’s reestablishment of the Benedictine Priory of Solesmes in 1833. Prosper Louis Pascal Guéranger (1805-1875) was ordained in 1827 a priest of the Diocese of Le Mans, France. In 1833 he purchased the property and buildings of the former Benedictine Abbey at Solesmes, which had been shuttered with the French Revolution. There, with a handful of other men, he turned Solesmes into a center of Roman liturgy (versus Gallican liturgy), historical and liturgical studies (St. Thérèse of Lisieux recalls her parents reading Guéranger’s Liturgical Year to her and her sisters as children), and Gregorian Chant (Solesmes versions of chant fill the Church’s official sacred music books to this day). Besides Guérenger’s 1833 reopening of the Solesmes Priory (later named an Abbey), other possible answers include Pius X’s 1903 motu proprio, Tra le Sollecitudini, or Dom Lambert Beauduin’s presentation at the 1909 Liturgical Conference in Malines, Belgium.

- False. Dom Lambert Beauduian, OSB (1873-1960), called the ministerial priesthood the “fundamental principle” to the restoration of the liturgy in his 1914 “manual” on the Liturgical Movement, Liturgy: The Life of the Church. He writes: “The superabundant source of all supernatural life is the sacerdotal power of the High Priest of the New Covenant. But this sanctifying power of Jesus Christ does not exercise here below except through the ministry of a visible hierarchy…. [Thus, liturgical piety] derives its transcendent character above all from what we can call this hierarchical character. It procures the full sanctifying influence of the visible priesthood of the mystical body of Jesus Christ for the members of this body. The life of God is in Christ; the life of Christ is in the hierarchy of the Church” (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1926, 1, 7).

- c. Pope Pius X. In his 1911 apostolic constitution, Divino Afflatu, Pope Pius X (reigned 1903-1914) established a new (and controversial) psalter for use in the Divine Office for the entire Church. In this same 1911 letter, he wrote, “As the arrangement of the psaltery has a certain intimate connection with all the divine office and the liturgy, it will be clear to everybody that by what we have here decreed we have taken the first step to the emendation of the Roman breviary and the missal, but for this we shall appoint shortly a special council or commission.” In 1913, two years later (literally, in Latin, abhinc duos annos), the Holy Father gave an update on the work, saying that the intervening years had been occupied with other more pressing tasks that hadn’t allowed him to move forward on liturgical reform. Thus, “in the judgment of wise and learned persons, all this would require considerable work and time. For this reason, many years will have to pass before this type of liturgical edifice, composed with intelligent care for the spouse of Christ to express her piety and faith, can appear purified of the squalidness brought by time, newly resplendent with dignity and fitting order” (Abhinc Duos Annos).

- e. Odo Casel. Odo Casel (1886-1948) was a Benedictine Monk of the Maria Laach Abbey in the Rhineland area of western Germany. The “theologian” of the Liturgical Movement, Casel articulated what he called Mysterientheologie, or “Mystery Theology.” This mystery-in-the-present claims that Christ and his saving work—and not simply his grace—are in some way present and manifest to the baptized of every age through the liturgy and the sacraments. That is, the entirety of God’s “plan of the mystery” (Ephesians 3:9), the pinnacle of which is the saving action of Christ, reveals itself in our liturgical presence. Of this Mystery Theology, Pope Benedict says: “[O]ur age has been called the century of the Church; it could just as well be called the century of the liturgical and sacramental movement…. Perhaps the most fruitful theological idea of our century, the mystery theology of Odo Casel, belongs to the field of sacramental theology, and one can probably say without exaggeration that not since the end of the patristic era has the theology of the sacraments experienced such a flowering as was granted to it in this century in connection with Casel’s ideas” (Ratzinger, Collected Works (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2016) 153).

- d. Romano Guardini. The Italian-born Romano Guardini (1885-1968) taught at the University of Berlin from 1923-1939, holding the Chair of Philosophy of Religion and Catholic World View. During these same years, he continued his work among college-aged students at the Castle Rothenfels, where he and students engaged religious, liturgical, and social questions of the day. The Nazis confiscated the Castle in 1939, along with relieving Guardini from teaching in the same year. Pope Benedict XVI, in his interview book Last Testament, recalls meeting Guardini at Burg Rothenfels: “In 1956 we [Benedict and his brother, Georg Ratzinger] went with a friend to Franconia, where an uncle lived, one of my mother’s brothers. So when we passed through Rothenfels, we thought, now we have to go up to the castle where Guardini had been bringing young people for decades. It was of course highly fitting that Romano Guardini walked out of the castle gate just then. We go up there, and what’s going on? Guardini walks out of the castle gate! [Laughs loudly] It was like a dream. He showed himself to be most delighted. ‘It’s strange who you bump into just because you’re there!’ Then we had a little chat” (London: Bloomsbury, 2017, 85).

- False. Dom Virgil Michel, OSB (1890-1938), “Father” of the American Liturgical Movement, best summarizes the relation between liturgy and Catholic Action (the social apostolate in the world) at the conclusion of his 1935 article, “The Liturgy the Basis of Social Regeneration.” He says: “Pius X tells us that the liturgy is the indispensable source of the true Christian spirit; Pius XI says that the true Christian spirit is indispensable for social regeneration. Hence the conclusion: The liturgy is the indispensable basis of Christian social regeneration.” Consider, too, the Catholic Worker Movement founded and developed by Dorothy Day (1897-1980), who writes, “You cannot receive the Blessed Sacrament without becoming sensitive to the inspirations of the Holy Spirit, and these inspirations are to be put into practice…. We can link up liturgy and sociology, in other words” (The Catholic Worker, February 1935, 7).

- c. Pius XII. Pope Pius XII (reigned 1939-1958) wrote Mediator Dei in 1947, the first encyclical on the topic of the sacred liturgy. The Holy Father begins, “Mediator between God and men, and High Priest who has gone before us into heaven, Jesus the Son of God quite clearly had one aim in view when he undertook the mission of mercy which was to endow mankind with the rich blessings of supernatural grace. Sin had disturbed the right relationship between man and his Creator; the Son of God would restore it…. [T]he Church prolongs the priestly mission of Jesus Christ mainly by means of the sacred liturgy” (1, 3).

- b. Active participation. In his 1903 motu proprio Tra le Sollecitudini, Pope Pius X wrote: “Filled as We are with a most ardent desire to see the true Christian spirit flourish in every respect and be preserved by all the faithful, We deem it necessary to provide before anything else for the sanctity and dignity of the temple, in which the faithful assemble for no other object than that of acquiring this spirit from its foremost and indispensable font, which is the active participation in the most holy mysteries and in the public and solemn prayer of the Church.” In making “this full and active participation by all the people…the aim to be considered before all else” (Sacrosanctum Concilium, 14), the Fathers of the Second Vatican Council should also be understood as having Pius X’s mind on what constituted active participation, namely, the worthy and attentive participation in the liturgy. Pius X, for example, is identified as “Pope of the Eucharist” since he encouraged frequent, even daily, communion in 1905. In 1910, he lowered the age of First Communion to about the age of discretion. These pastoral acts reveal his thinking on active participation.

- Success can be measured in many ways, but the ultimate measure is holiness, which honors God to the fullest. Apart from the holiness that many Liturgical Movement figures helped Christ’s faithful to attain, there are a number of figures who have been declared saints or whose cause for canonization has begun, such as: Pope St. Pius X, Pope St. John XXIII, Pope St. Paul VI, Pope St. John Paul II, Blessed Columba Marmion, Venerable Pius XII, Servant of God Prosper Guérnager, Servant of God Romano Guardini, and Servant of God Dorothy Day. All you saints, blesseds, and holy men and women: pray for us!