Ignatius Note-Taking and Journaling Bible. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2020. 1,290 pp. ISBN: 978-1621641902. $39.95 Paperback.

Of the printing of Bibles, there is no end (cf. Ecclesiastes 12:12). Whether it’s a new translation, a new typeface, the inclusion of study notes, or a fancy cover, the Bible continues to be the bestselling book in the world—and publishers know it. While digital books and Bible software abound, the reading of the Sacred Scriptures is nevertheless an experience where tangible contact with a physical volume (dedicated solely to the Biblical text) is irreplaceable.

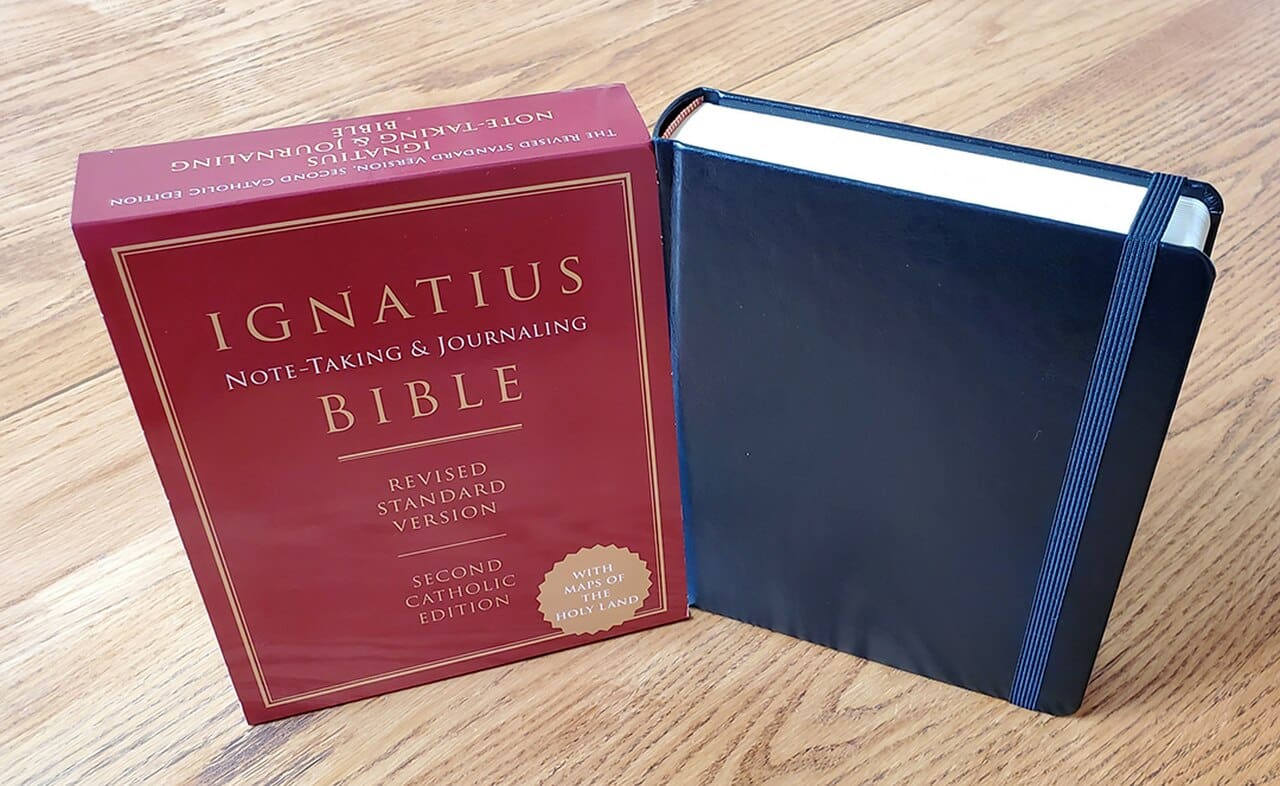

While new Bibles abound, the Ignatius Note-Taking and Journaling Bible published by Ignatius Press (2020) stands out in the midst of the Bible-publishing crush. Firstly, this Bible is gorgeously crafted. The Smyth-sewn binding holds the pages together in nearly-square dimensions (6.25” x 7.25”) and allows the Bible to lay flat whether you’re reading Genesis, Revelation, or anything in between. A synthetic soft black leather cover allows the nearly 1,300 pages of this volume to fit neatly and comfortably in the hand. Surprisingly, the cover is really quite remarkable in its feel, soft to the touch. A sturdy elastic band is built into the cover to keep the volume closed tight in transit, making it wonderfully portable.

The pages of the new Ignatius Bible are thin so as not to make the volume too bulky, but sufficiently thick for writing notes with a ballpoint pen. While the font used for the biblical text is small (7 point, Palatino), the cream-colored paper helps the sharply printed text catch the eye of the reader. The small font provides room for the two inches of lined writing space for taking notes on each page. While some may scoff at writing on the Sacred Page, such ample writing space harkens back to the “thick margins” which “became more and more crowded with the glosses of [medieval] scribes who prayed, studied, memorized, and recopied—in a word, celebrated—the text inexhaustibly.”[1]

An important feature of the Ignatius Note-Taking and Journaling Bible is that it employs the Second Edition of the Revised Standard Version (RSV-2CE), modified in accord with Liturgiam Authenticam in 2001. To “rephrase the Preacher’s melancholy observation…, ‘Of the making of many translations of the Bible there is no end!’” (Ecclesiastes 12:12). Indeed, “between the publication in 1952 of the Revised Standard Version and the publication in 1990 of the New Revised Standard Version, 27 English renderings of the entire Bible were issued.”[2] While one can certainly lament the dizzying deluge of translations,[3] each translation highlights how the handing on of the Scriptures from generation to generation enriches the Church through the “different ways by which the word of God is proclaimed, understood and experienced” (Pope Francis, Sacra Scripturae Affectus).

In this line, the RSV-2CE represents not only a deeply faithful translation, but an effort to pass on the patrimony of the Catholic tradition. The readers of this translation of the Bible will not only find a consistent word-for-word (formal equivalence) translation of the biblical text from the original languages, but with additional care being taken to consult the traditional Latin Vulgate “as an auxiliary tool…in order to maintain the tradition of interpretation that is proper to the Latin Liturgy” (Liturgiam Authenticam, 24). As the editors put it in the introduction to the 1966 RSV-CE, “critical evidence being evenly balanced, considerations of Catholic tradition have favored a particular rendering” of the Biblical text. The concrete payoff of such an approach is glimpsed, for example, when we read the traditional appellation given to the Blessed Mother in Luke 1:28: instead of “favored one,” as in the New American Bible, Revised Edition (NAB-RE), the RSV-2CE renders the Greek κεχαριτωμένη with the traditional, “full of grace.” This is not only an exegetical decision based on the sense of the utterly unique Greek verb, κεχαριτωμένη, but also a choice to take into account the longstanding Latin translation of this word by the phrase, gratia plena, which dates back to the second century—paralleling the Syriac translation. As the late Abbot Denis Farkasfalvy writes, the “interpretation of this choice of words [“full of grace”] is a matter of exegesis and theology and cannot be debated on purely grammatical grounds as a correct or an incorrect rendition.”[4] That said, the rendering of this Greek word into English by the phrase “full of grace” represents a consistent theological and exegetical understanding of the Catholic tradition for almost two millennia. Readers of the RSV-2CE can be confident in reading a text that incorporates the received tradition of the Latin West.

Another advantage of using the RSV-2CE is that its immediate predecessor, the RSV-CE, has the distinction of being the translation that was used in the Catechism of the Catholic Church (1997). That said, the RSV-2CE is slightly different from the RSV-CE. The move from the RSV-CE to the RSV-2CE did little more than to update the idiom of the English language. For example, the many thees and thous in the Old Testament, have been changed to a more modern form of expression, as seen in these verses from 2 Samuel 7:

“28 And now, O Lord GOD, art God, and thy words are true, and thou hast promised this good thing to thy servant; 29 now therefore may it please thee to bless the house of thy servant, that it may continue for ever before thee; for thou, O Lord GOD, hast spoken, and with thy blessing shall the house of thy servant be blessed for ever.” – RSV-CE

“28 And now, O Lord God, you are God, and your words are true, and you have promised this good thing to your servant; 29 now therefore may it please you to bless the house of your servant, that it may continue for ever before you; for you, O Lord God, have spoken, and with your blessing shall the house of your servant be blessed for ever.” –RSV-2CE

Practically speaking, the updating of language in the RSV-CE was done so as to prepare the text of the RSV-2CE for lectionary use in the English-speaking portions of dioceses in India. Translations made for liturgical use are “characterized by a certain manner of expression that differs from that found in everyday speech,” but consideration should also be taken to “employ the full possibilities of the vernacular language skillfully in order to achieve as integrally as possible the same effect as” the base language (Liturgiam Authenticam, 59). While many laud this updating of archaic language, others lament the loss of the traditional language of King James’ Authorized Version, from which the RSV derives its lineage. Nevertheless, the revision of the RSV-2CE was, strictly speaking, limited to updating language for liturgical use. The 2006 RSV-2CE remains the fruit of translators working from the best manuscript evidence of the 1940s and 50s, nearly 80 years ago. This also means that infelicities in the previous text went unchanged. For example, in the RSV-2CE, Genesis 3:6 states that Eve “also gave some to her husband.” This clause is “followed in the Hebrew text by the phrase ‘with her,’”[5] captured well in the ESV, the NABRE, the NRSV, and the Nova Vulgata: “she also gave some to her husband who was with her, and he ate” (ESV-CE, emphasis added). While the RSV-2CE is following the Vulgate in its translation, such a noteworthy difference should at least have a footnote indicating its omission. This is especially the case since the Nova Vulgata Editio is the volume to “be consulted as an auxiliary tool” (Liturgiam Authenticam, 24).

As St. Josemaria Escriva wrote, “How I wish your bearing and conversation were such that, on seeing or hearing you, people will say: This man reads the life of Jesus Christ” (The Way, n. 2). Ignatius Press’s contribution to biblical publishing will certainly provide such an opportunity. While no translation or edition of the Bible provides for every need, the Ignatius Note-Taking and Journaling Bible is a wonderful contribution to the life of the Church in the English-speaking world. This edition is well-suited for “the diligent reading of Sacred Scripture accompanied by prayer” that “brings about that intimate dialogue in which the person reading hears God who is speaking, and in praying, responds to him with trusting openness of heart (cf. Dei Verbum, n. 25)” (Benedict XVI, Address on the Occasion of the 40th Anniversary of Dei Verbum). For those who practice Lectio Divina with a Bible to hand, this edition of the biblical text offers ample space to jot down insights received in prayer that will endure for the lifetime of the Bible and beyond. As Pope Benedict XVI said, if Lectio Divina “is effectively promoted, [it] will bring to the Church—I am convinced of it—a new spiritual springtime.”

- Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis, Fire of Mercy, Heart of the Word: Meditations on the Gospel according to Saint Matthew, Chapters 1–25, vol. 1 (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1996–2012), 20. ↑

- Bruce Manning Metzger, The Bible in Translation: Ancient and English Versions (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2001), 117.↑

- See Bible Babel by Rev. Richard John Neuhaus. ↑

- Denis Farkasfalvy, The Marian Mystery: The Outline of a Mariology (New York: St Pauls, 2014), 58. ↑

- Scott Hahn and Curtis Mitch, Genesis: With Introduction, Commentary, and Notes, ed. Revised Standard Version and Second Catholic Edition, The Ignatius Catholic Study Bible (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2010), 22. See also David E.S. Stein, “A Rejoinder concerning Genesis 3:6 and the NJPS Translation,” Journal of Biblical Literature 134 (2015): 51–52. ↑