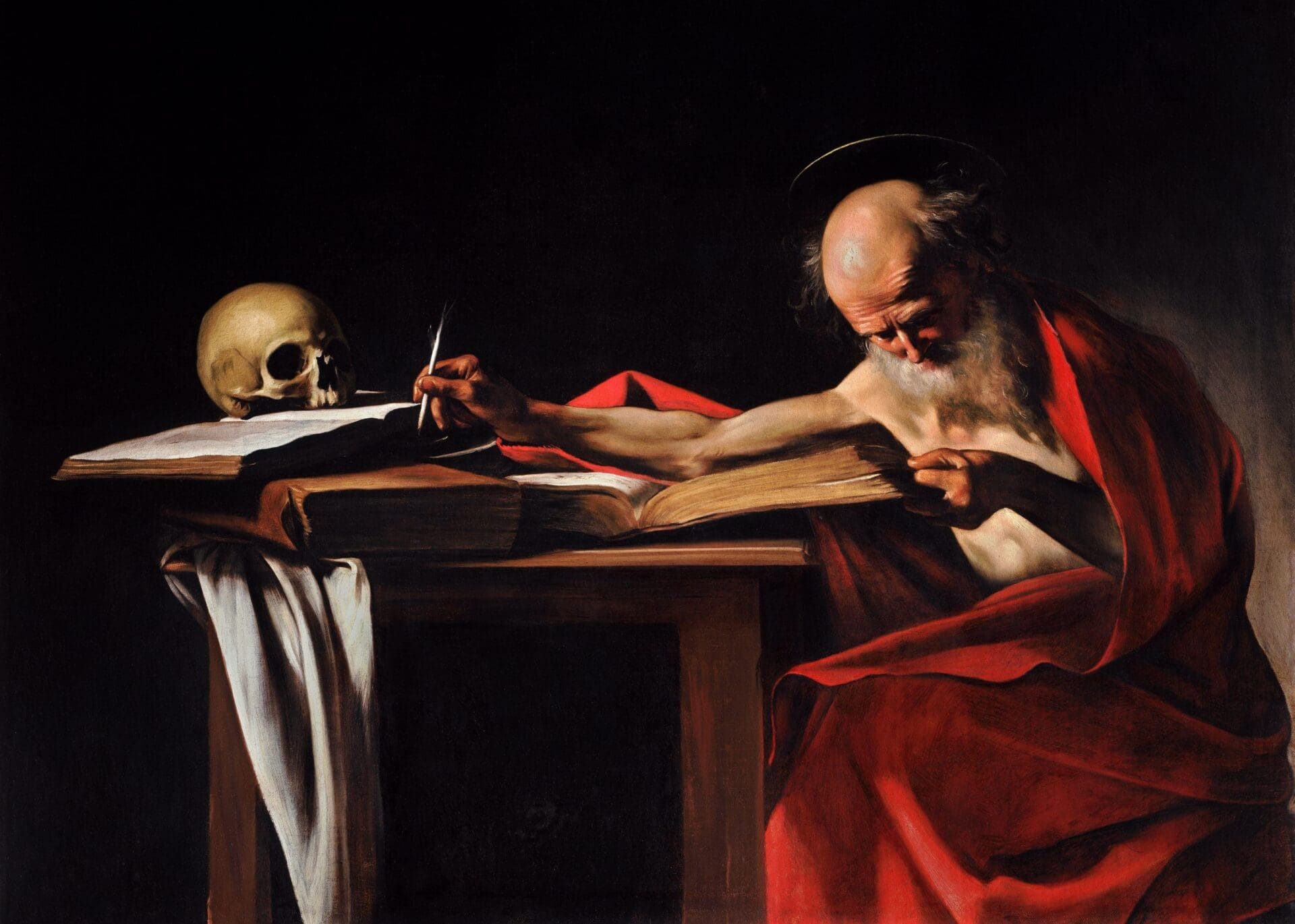

On February 22, the Feast of the Chair of St. Peter, in 1962, the year that the Second Vatican Council began, Pope St. John XXIII put pen to vellum. Before a solemn convocation of cardinals, bishops, and members of the faithful, he signed his new Apostolic Constitution after placing it on the high altar of St. Peter’s Basilica. It was Veterum sapientia, on promoting the study of Latin.

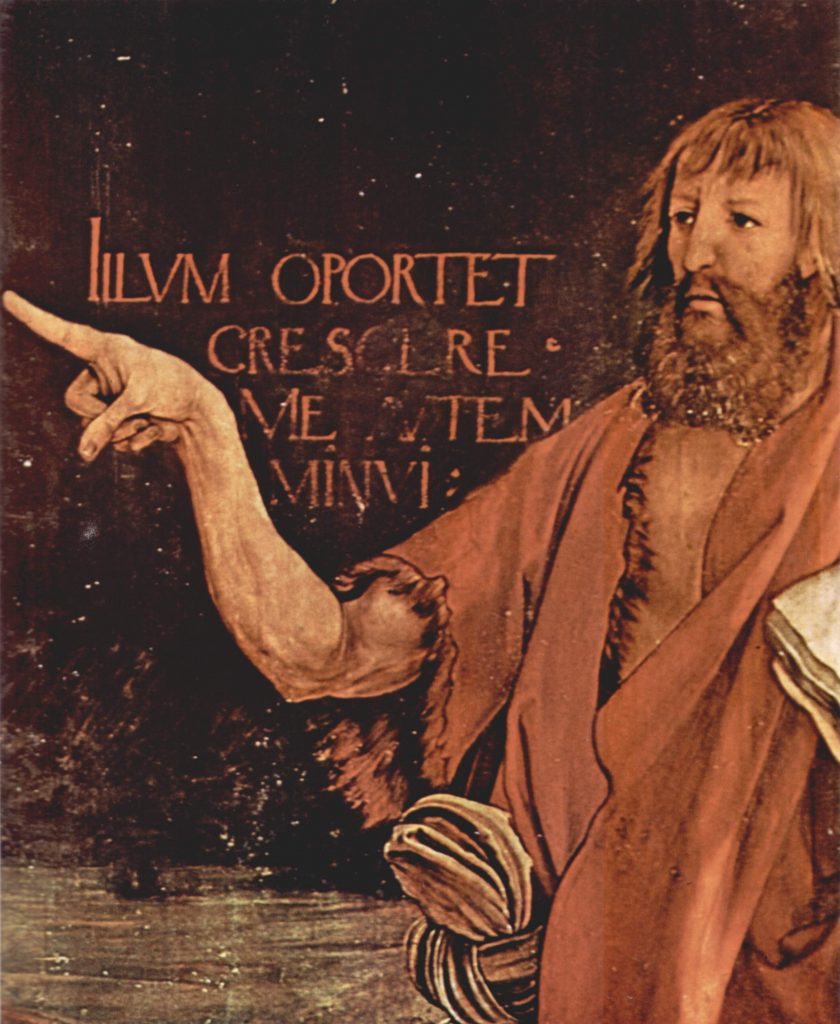

Echoing his predecessors, Pope John asserted that the Latin language, being universal, immutable, and non-vernacular, is uniquely suited for the Catholic Church. In fact, he claimed, it was no accident that the Word became flesh when he did, precisely when the Greek and Latin languages were ready to carry the truth of the Gospel to the nations. This was the design of the same providence that would root the Church’s visible headship not in Jerusalem but in the imperial city of Rome.

Veterum sapientia is not only about the Mass but about the whole life of the Latin Church and, indeed, the Church universal. Pope John directs that seminaries and other academies are to teach in Latin, use textbooks written in Latin, and ensure that their students become proficient in Latin. It is an unambiguous, rigorous document, one that Pope John meant to be taken seriously.

Even those familiar with Veterum sapientia may not know the companion document issued by the Sacred Congregation for Seminaries and Universities to assist in the implementation of Pope John’s mandate.[1] This document delineates requirements for teachers, exercises, examinations, and a full curriculum for Latin studies extending all the way to nine years! It specifies how seminaries and universities around the world should have Latin as their lingua franca for study.

None of this happened. Despite the mandate of the pope who called the Second Vatican Council, despite the stated intention of that same Council,[2] despite the statements of subsequent popes and Church documents,[3] it is not uncommon today for priests never even to have studied Latin at all—never mind the standing canonical requirement of good proficiency (“bene calleant”).[4] The situation among the lay faithful is even worse.

And yet, by the firm and gentle hand of providence, Latin has not yet been lost forever. In fact, there is clear growth in the use of Latin in the Mass and interest in Latin both in Catholic schools, especially those exploring the use of classical curricula, and in the thriving Catholic homeschooling movement. We are far from a revival of Latin on the scale of what was achieved in modern times with Hebrew through the efforts of scholars such as Eliezer Ben-Yehuda (1858-1922) in Israel, but there is interest. I suggest that it is time to accelerate that progress.

Nearly 60 years since Veterum sapientia, we must get serious about reviving Latin in the Latin Church. Despite the near total abandonment of the language, we now have tools that Pope John would have marveled at—the Internet, smart phones, and serious advances in language pedagogy. Actually, the Church has now fallen behind the world of secular Latin.

This is a pity because Pope John was right. The Church needs Latin. We are, after all, a global community, an ancient community, and an everlasting community.

Pope John was right. The Church needs Latin. We are, after all, a global community, an ancient community, and an everlasting community.

A Global Community

In recent years, it has become a common occurrence for disputes to erupt over the exact meaning of a single word or phrase in Church documents. Amoris laetitia, for instance, was scrutizined and debated down to its footnotes for months before the official Latin text was even published.[5] The Church is a global community, and texts are released online, often in as many as eight languages, evoking instant worldwide commentary.

Unfortunately, when that commentary centers on a fine point of interpretation, we have a problem, which is that the standard text of a Church document is not the online version but instead usually that published in the official record of the Holy See, the Acta Apostolicae Sedis AAS)—which is, however, often about two years behind current debates and conversations on a given text. Further, when a Church document is released in eight languages at once, which version is the authoritative document? The English, Italian, and Spanish versions, for instance, may differ in how they express a certain point. No one can debate the meaning of a single word or phrase without first establishing what that word or phrase is. No matter what went into the drafting and editing process, at the end of the day, there has to be a standard version. Latin used to be and remains the obvious choice.

As a standard language for global use, Latin not only avoids favoritism toward any given modern language, it also places current Church documents in line with the great majority of its historical documents. Words and phrases are then contextualized within the rich and refined ecclesiastical vocabulary extant in the Latin language. The Church thought and wrote in Latin for centuries. We are the same Church today, not a different one, so it makes sense that we, too—certainly in our official documents—should think and write in Latin.

An Ancient Community

We are not only a global community of contemporaries but also an ancient community. A sudden rupture in our technical vocabulary would be bad enough, but the abandonment of the very language in which the Church has thought for centuries cuts us off from a conversation spanning generations. When even our official documents, the acts of our synods, and so forth, are fragmented into so many distinct tongues, we risk confusion in the present and rupture from the past.

The same is true, of course, in that “foundation and confirmation of all Christian practice”—Sunday Mass.[6] Language binds culture. It transmits identity. It shapes community. And, the reverse is also true: our sense of culture, identity, and community influence our language. Crucial, then, to the meaning of the Mass is the understanding that it, too, is a global and ancient sacrifice, not just the expression of this particular group of people in this particular town on this particular Sunday morning. The Mass is the pure sacrifice of Christ re-presented “among the nations, from the rising of the sun to its setting” (Malachi 1:11). Through the Mass, the Church, Christ’s Mystical Body, participates in the single self-offering of her Head. This means, in turn, that the community that forms through the Eucharistic sacrifice is the whole Church, in heaven, in purgatory, and on earth.

So, while there are benefits to using vernacular languages in the liturgy, particularly when these vernacular languages are themselves keyed to a hieratic register, it is also important to maintain a sense of continuity. In the Latin Church, this means the Latin language. A global and ancient community grows in solidarity through a global and ancient language. What a pity when Latin in the Mass strikes Roman Catholics as utterly foreign and incomprehensible when it should evoke instead a sense of belonging and ancestral pride!

What a pity when Latin in the Mass strikes Roman Catholics as utterly foreign and incomprehensible when it should evoke instead a sense of belonging and ancestral pride!

Imagine an immense library containing the only records of western Catholic thought and experience. Now imagine that library engulfed in flames and burning to the ground. Just a few volumes here and there survive. This is what losing Latin means for Catholics. And what’s worse, keeping Catholics in ignorance of Latin means that they will not even know what has been lost! It is a damnatio memoriae of the worst kind. Ironically, only those who know Latin can know what is at risk of being lost. Those who can’t read Latin and claim that it isn’t worth preserving quite literally don’t know what they’re talking about. How could they?

Those who can’t read Latin and claim that it isn’t worth preserving quite literally don’t know what they’re talking about. How could they?

An Everlasting Community

If it is foolish to judge the past without knowing it, we might say something analogous about the future. You and I will most likely not be on this earth till Christ comes again, but the Church will. English is widespread today, but for that very reason it is always changing. Where will it be in a century? A millennium? Will Catholics of the 31st century look back at our present era as a lost age, an age with unreadable records in an otherwise consistent stream? If destroying knowledge of the past is a damnatio memoriae, we damn ourselves to obscurity—and thereby sell future generations short—by divorcing our most important thoughts from the grand record of the Western Church. It is much more likely that Catholics a millennium from now will be able to read Latin rather than 21st-century English, Italian, Spanish, or any of the other languages in which Church documents are being published. What injury are we prepared to inflict on the poor theologian a thousand years hence who opens his catena of Church documents to find that the Magisterium of our own day has fractured, at least linguistically, into a thousand pieces?

What should we do?

Now is the time for the Church to recover Latin, but how might this be done? I suggest that the first step is nothing other than fidelity to Church law and the Second Vatican Council’s stated intentions. This includes the following:

- Seminaries should require serious study of Latin to the point that when a man is ordained a priest he can at least read and write Latin competently.[7]

- Seminaries should ensure that newly ordained priests are able to celebrate Mass in Latin and sing Gregorian chant.[8]

- Pastors should teach their parishes the basic prayers (e.g., the Pater Noster, Ave Maria, etc.) in Latin and the basic Gregorian chants, particularly those contained in the booklet Iubilate Deo, which Pope St. Paul VI issued as a minimum repertoire for Roman Catholics.[9] There is a reason this book bears the subtitle: Easier Gregorian Chants That the Faithful Are Supposed to Learn in Conformity with the Intention of the Second Vatican Council’s Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy.

Practically speaking, these initial tasks might be accomplished by:

- Ensuring that seminarians start their study of Latin when they begin their course of studies and continue with it throughout.[10]

- Using modern language pedagogy with proven effectiveness for a greater number of students than formal grammar and translation alone.

- Requiring proof of an appropriate level of Latin proficiency before seminarians are admitted to the study of theology.[11]

- Having Catholic grade schools and high schools teach Latin whenever possible, or at least basic prayers and chants. The same goes for religious education and homeschooling curricula.

- Having children sing at Sunday Masses the chants that they have learned. The chants should be coordinated with the liturgical calendar (e.g., the Rorate caeli during Advent, the Attende, Domine during Lent, the Ave maris stella on Marian feasts). This will integrate the next generation of Catholics into the Eucharistic celebration and create an experience of using Latin in worship.

- Regularly using Latin in the Mass in every parish. For example, a parish might rotate through parts of the Order of Mass in Latin throughout the year and use seasonal antiphons. This could also bring multi-lingual parish communities together, allowing them to sing and respond in unison.[12]

- Encouraging priests to take part in ongoing Latin education. The annual Veterum Sapientia Latin workshop (www.veterumsapientia.com) exemplifies an unintimidating, modern, and effective approach.

There are also steps that the Church could take on higher levels, such as:

- Increasing the staff of the Holy See dedicated to working with the Latin language.

- Publishing Church documents in Latin first, with the goal of returning to the point where they are composed in Latin.

- Holding synods and other international gatherings in Latin.

- Providing scholarships for Latin teachers in Catholic schools to learn methods with the greatest proven effectiveness.

- Fostering religious orders and associations of the faithful especially dedicated to Latin.

- Providing scholarships for Catholic students from around the world to study Latin intensively. Ideally, this would mean having students come to Vatican City in Rome to live for a significant period of time in a spoken-Latin environment.

Some of these suggestions would require significant funding. Others would be free and could even save money (e.g., on licensing fees for music). All of them would take effort, a commitment not to give up on Latin, and patience. Rome wasn’t built in a day—and neither was its language. It will take time to revive Latin, but it can be done, and any steps we take are better than none.

Rome wasn’t built in a day—and neither was its language. It will take time to revive Latin, but it can be done, and any steps we take are better than none.

Answering Objections

Given the situation of the world and the Church herself these days, the revival of an ancient language may seem like the last thing we should be worried about. There are bound to be objections to my proposal. Allow me to reply briefly to some of them.

Doesn’t the Church have more pressing needs?

Undoubtedly. It is my hope that those needs will also be served by the revival of Latin. To take a timely example, the present crisis with the novel coronavirus has led to a variety of responses and opinions about the rights and responsibilities of bishops, priests, and the lay faithful. When must a priest administer the Eucharist? Can a bishop forbid public Masses? What about confession or the last rites? Given that the Church has encountered epidemics in the past, there exists significant literature—in Latin—with carefully considered replies to questions such as these.[13] Unfortunately, these sources are rarely consulted. In any case, it is hard to imagine how keeping Catholics ignorant of Latin will help the Church address her other problems.

Couldn’t we be helping the poor instead?

It is a crime when we Catholics fail in our duty to the poor. Still, such failures are not because of Latin but because of indifference and selfishness. There is no reason we can’t dedicate resources both to the Latin language and to outreach to those in need. In fact, education itself is a service to the poor. Why should Latin be the privilege of the wealthy?

Okay, fine, so let’s revive Latin—but why stop there? Why not go back to Greek, Hebrew, or Aramaic while we’re at it?

These languages are also important and worth recovering! After all, they are the original languages of Scripture. However, in terms of liturgical language, the Roman Rite was only solidified in conjunction with Latin. While Greek was once used for the Eucharistic sacrifice even in the West, the Roman Rite had not yet concretized and matured. For as long as the Roman Rite has truly existed, certainly since the time of the Gregorian Sacramentary, Latin has been its language. In terms of non-liturgical usage, the vast majority of Catholic thought and experience in the West has come down to us in Latin. It is simply a fact that Latin has remained in continuous usage in Western Catholicism in a way that other languages have not.

Are you saying that you want to eliminate vernacular languages in Mass or other prayers?

Not at all. There is a difference between preserving Latin and eliminating other languages. By analogy, just as the Church says that Gregorian chant is especially suited to the Roman Liturgy and should hold the “first place” in liturgical celebrations while not excluding other musical forms, so also giving greater attention to Latin does not mean eliminating the vernacular.[14]

Why do you want the Church to use a language no one understands?

I don’t. I want Latin, the historic language of the Latin Church, to be understood. This is not about the imposition of some arbitrary foreign language but about empowering Catholics so that Latin will no longer be foreign to them. If children grow up with general use of Latin in their parishes, it will be familiar to them, not alien.

Isn’t this just a form of clericalism?

No. While I suggest prioritizing the education of seminarians and priests in Latin, I also encourage all Catholics to become familiar with and even to learn Latin. Prioritizing the formation of clergy is meant to have a trickle-down effect, but there is also need of a concurrent grassroots movement among the laity, especially in the education of children. Those children will be our future bishops, abbots, and parents. They will be our future Catholics, period. Reviving Latin is about empowering clergy and laity alike. Better educated clergy will be better equipped to serve the laity, and better educated laity will be more empowered to engage Catholic thought directly. Shirking the responsibility to give people access to their own tradition and instead deliberately fostering ignorance in the laity is the real clericalism.

Good Doesn’t Mean Perfect

As Dr. Nancy Llewellyn, accomplished teacher of Latin and champion of its revival, has observed, we can have dead perfection or living imperfection. Christians will not become Ciceronians overnight—or maybe ever. Re-familiarizing Latin Catholics with their language will be messy, but life is messy. We need the courage and decisiveness of Pope John XXIII’s vision. The Church should not lock her treasures up like old china, to be looked at on occasion but never touched. Instead, let us open the cabinet and set out our very best—even if we break a few dishes in the process. Let us give the faithful their inheritance to use.

- Acta Apostolicae Sedis 54 (1962): 339–68. ↑

- Sacrosanctum Concilium, no. 36. ↑

- E.g., Musicam sacram, no. 47; Notitiae 9 (1973): 153–154; Voluntanti obsequens (1974); Dominicae coenae, no. 10; Code of Canon Law, can. 249; Sacramentum caritatis, nos. 42 and 62. For a much fuller catalogue of papal statements on Latin since Vatican II, see Yorick Gomez Gane, Pretiosus thesaurus: La lingua latina nella Chiesa oggi (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2012). ↑

- Code of Canon Law, can. 249. ↑

- See, for example, Fr. D. Vincent Twomey, SVD, “What’s wrong with an Amazonian Rite?”, at The Catholic World Report, May 20, 2020. URL: https://www.catholicworldreport.com/2020/05/20/what-wrong-with-an-amazonian-rite/#sdfootnote12anc [accessed October 20, 2020]. ↑

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, no. 2181. ↑

- Optatam totius, no. 13; and Code of Canon Law, can. 249. ↑

- Sacramentum caritatis, no. 62. ↑

- Sacrosanctum Concilium, no. 36; Musicam sacram, no. 47; and Sacramentum caritatis, no. 62. As for the obligation to teach the faithful Latin prayers and chants as repeated by Pope Benedict XVI’s Sacramentum caritatis, no. 62, it is important to note that the English translation available from the Holy See does not accurately render the authoritative Latin text. The Latin says neque neglegatur copia ipsis fidelibus facienda ut notiores in lingua Latina preces ac pariter quarundam liturgiae partium in cantu Gregoriano cantus cognoscant, which is better rendered “and there should be no failure to empower the faithful themselves to know the more common prayers in Latin as well as the chants of certain parts of the liturgy in Gregorian chant.” The English translation provided by the Holy See says only that “the faithful can be taught.” ↑

- Cf. the Congregation for the Clergy’s 2016 document on priestly formation, The Gift of the Priestly Vocation, no. 183. ↑

- Cf. the Congregation for Catholic Education’s 1985 Ratio fundamentalis institutionis sacerdotalis, no. 66. ↑

- Cf. Sacramentum caritatis, no. 62; and the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, Guida per le grandi celebrazioni (2014), no. 12. ↑

- One example is the Tractatus de sacramentis administrandis tempore pestis by Francesco Maria Villa (published in 1657), a work is specifically dedicated to the question. But more recent sacramental manuals, such as Felice Cappello’s Tractatus canonico-moralis de sacramentis, include sections on ways to administer sacraments in time of epidemic as well as detailed analyses of the rights and obligations surrounding the sacraments in those circumstances. ↑

- Sacrosanctum Concilium, 116. ↑