“‘A living and tender love’ for the written word of God.” So begins Pope Francis with the release of his apostolic letter, Scripturae Sacrae Affectus, his second on the Sacred Scriptures in a year. He published his first apostolic letter on this theme, Aperuit Illis, on September 30, 2019, establishing the 3rd Sunday of Ordinary Time as the “Sunday of the Word of God” (AI, 3).

In the title of the most recent letter, Scripturae Sacrae Affectus, Pope Francis unites the title of this apostolic letter with the text of the collect for the Memorial of St. Jerome: “O God, who gave the Priest Saint Jerome a living and tender love for Sacred Scripture, grant that your people may be ever more fruitfully nourished by your Word and find in it the fount of life.” In this way, Pope Francis combines a renewed invitation to encounter the voice of the Lord in the Sacred Scriptures with a joyful remembrance of the witness of Saint Jerome on the 1,600th anniversary of his death.

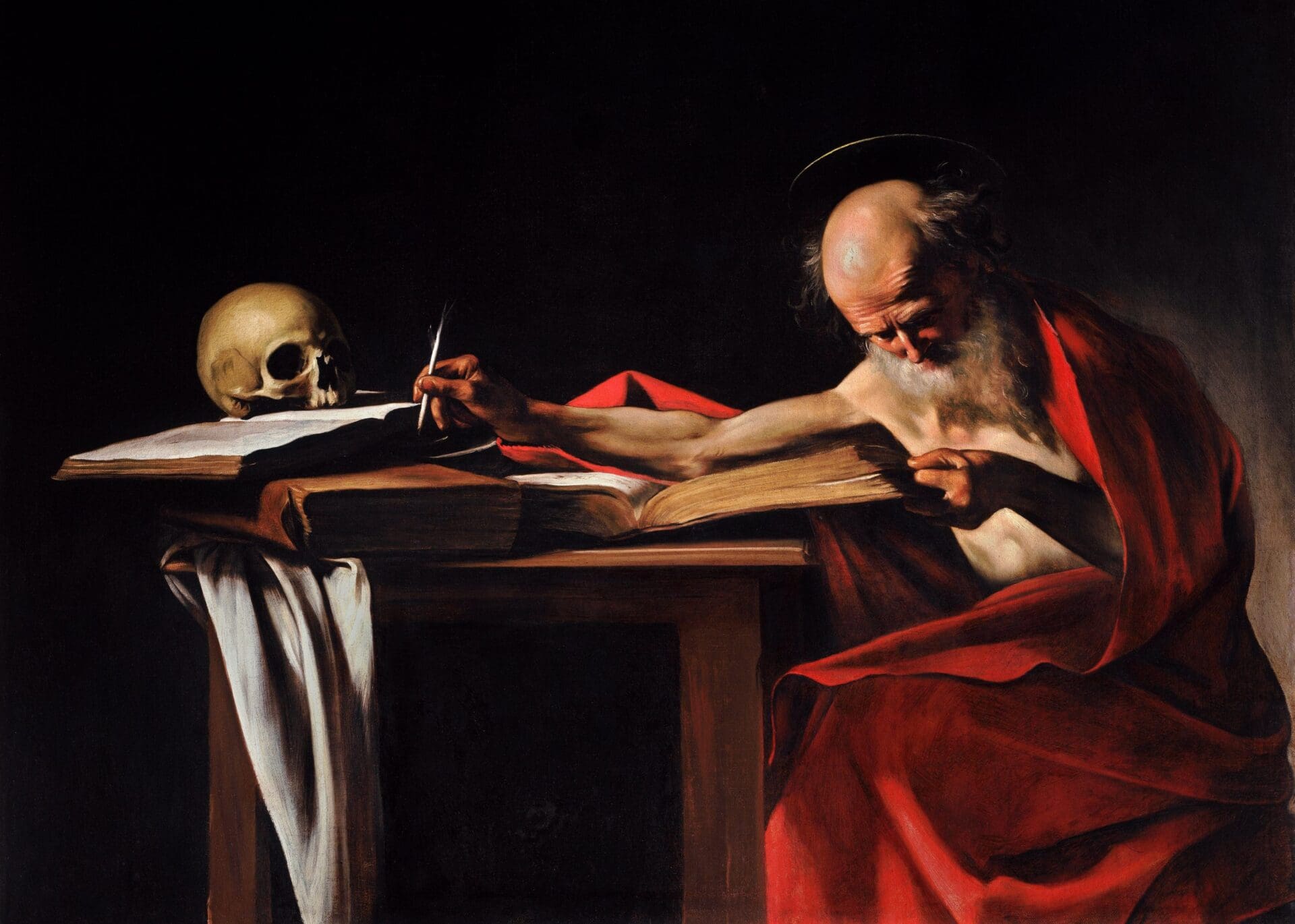

St. Jerome was born around A.D. 347 at Stridon in Dalmatia (modern day Croatia), and early on in his life Jerome “entrusted himself to the Lord whom he had always sought and known in the Scriptures” (Francis, SSA). Indeed, so intense was St. Jerome’s love for the sacra pagina that one of Jerome’s contemporaries observed that “‘he is always occupied in reading, always at his books: he takes no rest day or night; he is perpetually either reading or writing something’” (Francis, SSA). This was not merely some intellectual project for Jerome. Rebuked in a dream for being a “Ciceronian” rather than a Christian—that is, more intent on learning Latin than learning the truth of Christ—Jerome’s studies became “a spiritual exercise and a means of drawing closer to God” (Francis, SSA).

Intertextual Encounter

Reading Scripturae Sacrae Affectus, one is struck by the continued emphasis of Pope Francis on encountering the voice of the Lord in the Sacred Scriptures. Indeed, Pope Francis’ apostolic exhortation on “The Joy of the Gospel,” Evangelii Gaudium, comes back to the theme of “encounter with God’s word” (153) several times (152–3, 249, 262). Such a concern for scripture was also a major theme of Pope Benedict XVI, who released his own apostolic exhortation, “On the Word of God,” Verbum Domini, on the feast of St. Jerome in 2010. At the beginning of his pontificate, Pope Benedict XVI made this prognostication and challenge on the 40th anniversary of the Second Vatican Council document on scripture, “Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation,” Dei Verbum:

“Lectio divina: the diligent reading of Sacred Scripture accompanied by prayer brings about that intimate dialogue in which the person reading hears God who is speaking, and in praying, responds to him with trusting openness of heart (cf. Dei Verbum, n. 25). If it is effectively promoted, this practice will bring to the Church—I am convinced of it—a new spiritual springtime.”

Likewise, in Evangelii Gaudium, Pope Francis sets forth some excellent questions to ask as one meditates on the Sacred Scriptures: “Lord, what does this text say to me? What is it about my life that you want to change by this text? What troubles me about this text? Why am I not interested in this? Or perhaps: What do I find pleasant in this text? What is it about this word that moves me? What attracts me? Why does it attract me?” (EG, 153). Such questions help draw the hearer into an encounter with the Lord that is the basis from which the sharing of the gospel takes place: God’s word, grasped by the one who hears, is passed along to others. Indeed, all “the Doctors of the Church—particularly those of the early Christian era—drew the content of their teaching explicitly from the Bible” (Francis, SSA). Pope Francis also notes, “as Dei Verbum teaches, the Bible constitutes as it were ‘the soul of sacred theology’ and the spiritual support of the Christian life” (Francis, SSA).

The Word Made Words

As both popes recognize in their own writings, the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy re-emphasizes that in proclamation of the Sacred Scriptures in the liturgy, “it is [Christ] Himself who speaks…in the Church” (SC 7). Many are familiar with Dei Verbum’s teaching that the “Church has always venerated the divine Scriptures just as she venerates the body of the Lord, since, especially in the sacred liturgy, she unceasingly receives and offers to the faithful the bread of life from the table both of God’s word and of Christ’s body” (DV 21). St. Jerome draws us into an examination of conscience on this point:

“For me, the Gospel is the Body of Christ; for me, the holy Scriptures are his teaching. And when he says: whoever does not eat my flesh and drink my blood (Jn 6:53), even though these words can also be understood of the [Eucharistic] Mystery, Christ’s body and blood are really the word of Scripture, God’s teaching. When we approach the [Eucharistic] Mystery, if a crumb falls to the ground we are troubled. Yet when we are listening to the word of God, and God’s Word and Christ’s flesh and blood are being poured into our ears yet we pay no heed, what great peril should we not feel? (Jerome’s Commentary on the Psalms [In Psalmum 147: CCL 78, 337–338]).

In the words of Pope Francis, “Without an understanding of what was written by the inspired authors, the word of God itself is deprived of its efficacy (cf. Mt 13:19) and love for God cannot spring up” (Francis, SSA). As Jerome writes to the priest, Nepotian: “the word of the priest must be flavored by the reading of Scripture. I do not wish that you be a disclaimer or charlatan of many words, but one who understands the sacred doctrine (mysterii) and knows deeply the teachings (sacramentorum) of your God” (Jerome, Letter 52.8). Jerome’s advice “to the Roman matron Leta about raising her daughter was this: ‘Be sure that she studies a passage of Scripture each day…. Prayer should follow reading, and reading follow prayer…so that in the place of jewelry and silk, she may love the divine books’” (Benedict XVI, Verbum Domini, 72; Jerome, Letter 107.9,12).

Model Translation

While taking St. Jerome as a model of hearing the Lord’s voice in the Sacred Scriptures dominates much of Pope Francis’ Scripturae Sacrae Affectus, he also sets forth Jerome as a model for inculturation through his monumental work of translation: “By his translation, Jerome succeeded in ‘inculturating’ the Bible in the Latin language and culture. His work became a permanent paradigm for the missionary activity of the Church” (Francis, SSA). It is through his translation of the Bible from Greek and Hebrew into the Latin language, into what we know as the Vulgate, that “Medieval Europe learned to read, pray and think from the pages of the Bible translated by Jerome” (Francis, SSA). It is for this reason that the norms on principles of liturgical translation set forth in Liturgiam Authenticam (2001) state that while the Sacred Scriptures are to be translated from the original languages, the “Nova Vulgata Editio…is normally to be consulted as an auxiliary tool…in order to maintain the tradition of interpretation that is proper to the Latin Liturgy” (LA, 24), so that what has taken on “new accents and new resonances throughout the centuries” can be preserved (Francis, SSA).

Devoted Student

The Bible is a hard book to read. St. Jerome’s genius was to combine an “absolute and austere consecration to God” with a “commitment to diligent study aimed purely at an ever deeper understanding of the Christian mystery” (Francis, SSA). Jerome sought the Lord on his knees, at prayer, always with a book at hand. He spent long years studying to acquire facility in biblical languages, historical study, philological expertise, and textual criticism in order to hear the Lord’s Voice and be a guide for so many people who were not able to unlock the meaning of the biblical texts themselves. One might recall here the story St. Augustine tells of beginning to read the Scriptures: St. Ambrose recommended that he read the Book of the Prophet Isaiah. Unfortunately, Augustine read the “first part of this book” and it “was incomprehensible” to him “and, assuming that all the rest would be the same, [he] put it off, meaning to take it up again later, when [he] was more proficient in the word of the Lord” (Boulding, Confessions 9.5.13).

In all this struggle to understand the Scriptures, what is most essential is to seek the Lord through prayer and asceticism so as to become familiar with his manner of speech through diligent study. This is the two-fold pattern that Jerome sets out for us. Those like St. Jerome can exercise a certain “‘diaconal’ function on behalf of the person who cannot understand the meaning of the prophetic message” (Francis, SSA). Nevertheless, it was “by assiduous reading and constant meditation that [Jerome] made his heart a library of Christ” (Francis, SSA: quoting Nepotianus), and so it must be for us. Pope Francis puts forth the 16th centenary of Saint Jerome’s death “as a summons to love what Jerome loved, to rediscover his writings and to let ourselves be touched by…the advice that Jerome unceasingly gave to his contemporaries: ‘Read the divine Scriptures constantly; never let the sacred volume fall from your hand” (Francis, SSA).