The Second Vatican Council’s document Lumen Gentium (LG), “The Dogmatic Constitution on the Church,” gives many descriptive names for the Church, but perhaps none took root more widely in the post-conciliar years than “People of God” (LG, 9-17), often used to emphasize a “bottom up” model of the Church, sometimes with a strikingly anthropocentric turn associated with the word “community.”

In 1966, Jesuit Avery Dulles wrote that Lumen Gentium struck a “democratic” tone because it spoke of the Church’s mission in terms of “service rather than domination.”[1] Similarly, the Abbott-Gallagher translation of the documents of Vatican II added an explanatory footnote to the use of the phrase, noting that “People of God” met a “profound desire of the Council to put greater emphasis on the human and communal side of the Church, rather than on the institutional and hierarchical aspects which have sometimes been overstressed in the past….”[2]

This anti-hierarchical bias continued to grow in some quarters, such that in 2011 Notre Dame theology professor Father Richard McBrien could give an interpretation of “People of God” this way: “Who or what is the church? It is first and foremost people. It is also an institution. But it is primarily a community. The church is us.”[3] This “People-of-God principle,” as he called it, was expressed “in parish councils, in base communities, in the multiplication of ministries, and particularly in ministries associated with the liturgy, education and social justice.” This reactionary postconciliar emphasis on the Church as the People of God nearly eclipsed perhaps the most prominent ecclesiological concept leading up to the Council: the Mystical Body of Christ , the notion that the Church is the continuing action of Christ in the world, operating mystically as both Head and Members.

This rediscovery of the theology of the Mystical Body of Christ, then, is not simply a concern of the academic specialists, but an explosive idea which was foundational to the entire concept of lay liturgical participation so universally promoted after the Second Vatican Council, and so frequently understood at only the shallowest level as a mere external busyness.

Denis McNamara

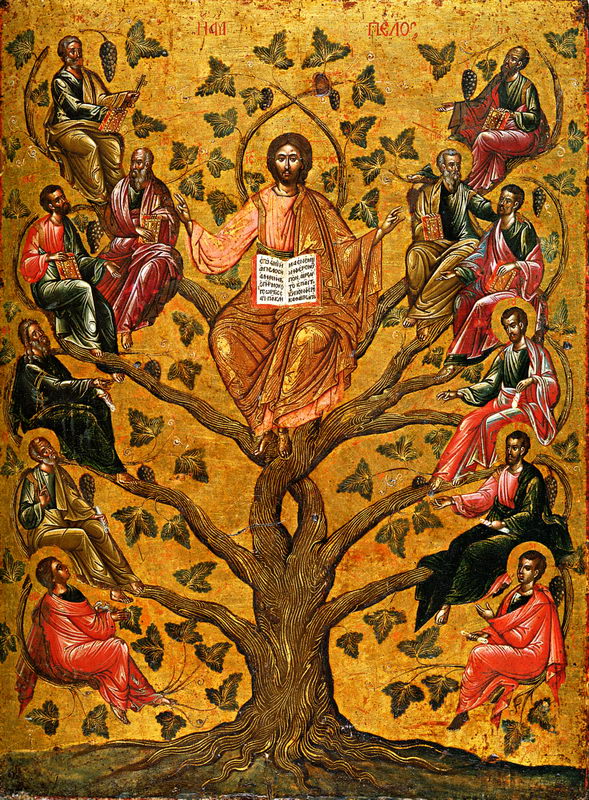

In our day, more than 50 years after the Council, rediscovery of Mystical Body theology provides many helpful insights in understanding what “active participation” really means. Indeed “new People of God” (LG, 9) is an apt and deeply scriptural name for the Church, since God called the chosen people in order to form and save them as a corporate body rather than as individuals. But Christ took this gathered people and raised the stakes, incorporating them into his own body, grafting them on to the vine of his own divine and human natures so that they might live with him, die with him, and rise with him.[4] This Mystical Body, which includes all of the baptized, not simply ordained ministers, celebrates the Paschal Mystery in the Church’s liturgy.

Consequently, when united to the ordained minister in the liturgy, the laity “are” Christ, and therefore the concept of participation takes on profound importance in modern liturgical theology. The lay faithful make a real priestly offering by virtue of their baptismal priesthood, and therefore join their offering of self to that which Christ makes to the Father. They therefore share in the glorification and resurrection that Christ enjoys at God’s right hand. This rediscovery of the theology of the Mystical Body of Christ, then, is not simply a concern of the academic specialists, but an explosive idea which was foundational to the entire concept of lay liturgical participation so universally promoted after the Second Vatican Council, and so frequently understood at only the shallowest level as a mere external busyness. Today’s understanding of Conciliar liturgical theology can be enriched by a second look at Mystical Body theology and the proper understanding of “community” as those who assemble for corporate worship as the mystici corporis Christi.

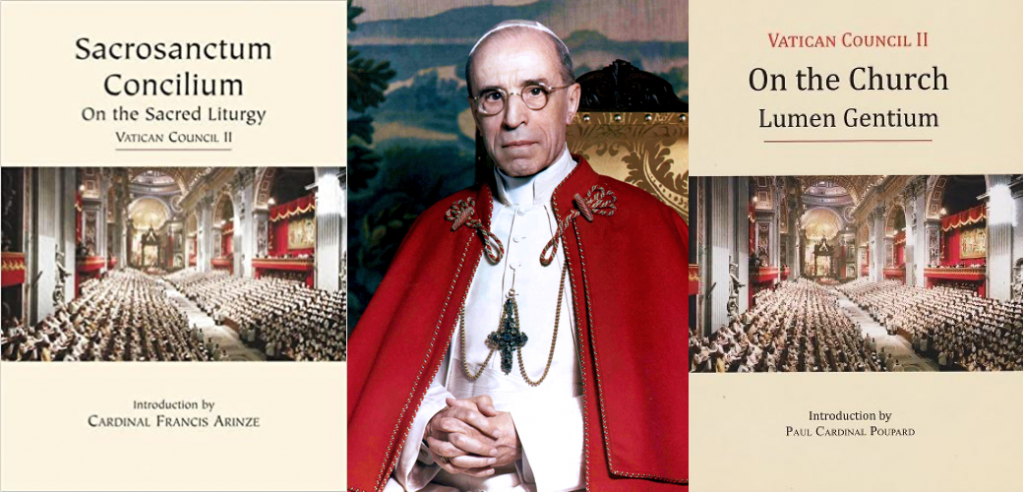

Pius XII and Mystici Corporis

The promotion of Mystical Body theology took a great leap forward in 1943 with Pius XII’s encyclical Mystici Corporis Christi (MC).[5] Teaching authoritatively, the pontiff makes it clear that he is clarifying ideas that are already present in the Church, encouraging that which is true and correcting errors.[6] His text shows a hint of defensiveness, beginning with the claim that the doctrine was “taught us by the Redeemer Himself” (MC, 1), and later he reminds those who think the doctrine “dangerous” that mysteries “revealed by God cannot be harmful to men…” (MC, 10).

Mystici Corporis says surprisingly little about the implications of the doctrine on liturgy, but a few insights can be gleaned which would be developed four years later in its sister encyclical, Mediator Dei (MD). One of his purposes in writing Mystici Corporis, Pius XII notes, is “to bring out into fuller light the exalted nobility of the faithful who in the Body of Christ are united with their head” (MC, 11). Later he makes the point that though the Body of Christ is subordinate to the Head, “they have the same nature” (MC, 46) and then extends that connection to human nature, which Christ took upon himself to make “His brothers according to the flesh partakers of the divine nature” (MC, 43). This divinization of the members of the body occurs through sacred rites of the Church, what Pius XII identifies as “participation in the same Sacrifice” of Christ (MC, 69).

Pius XII calls the earthly priest one who “acts as the viceregent not only of our Savior, but of the whole Mystical Body and each one of the faithful” (MC, 82). But then he strikes the salient point which begins to establish the role of the laity in worship: united with the priest in prayer and desire, the faithful as well “offer to the Eternal Father a most acceptable victim of praise and propitiation…” (MC, 82). This earthly worship by the full Mystical Body, then, allows lay participation in Christ’s perfect self-offering, since he offers not only himself, but “in Himself, His mystical members as well.” The laity’s important role in worship here finds its foundation while preserving the liturgy’s hierarchical nature and the uniqueness of the ordained priesthood.

Mediator Dei and the Mystical Body

In Pius XII’s 1947 encyclical Mediator Dei, this pontiff addressed the growing interest in liturgy during the previous decades, known collectively as the Liturgical Movement. The first encyclical in the history of the Church completely dedicated to liturgy, it clearly positions worship in relation to the Mystical Body, a phrase used 25 times through the text. He begins by defining the priestly life of Christ continuing “down the ages in His Mystical Body, which is the Church” (MD, 2-3), and later gives a remarkably succinct and complete definition of the sacred liturgy as “the public worship which our Redeemer as Head of the Church renders to the Father, as well as the worship which the community of the faithful renders to its Founder, and through Him to the heavenly Father. It is, in short, the worship rendered by the Mystical Body of Christ in the entirety of its Head and members” (MD, 20).

Pius XII is careful to maintain the essential distinctiveness of the ordained priesthood, noting that not all in the Body have the same powers (MD, 39); that ministerial priesthood does not “emanate from the Christian community” (MD, 40); and that ordination leaves an “indelible ‘character’” (MD, 42) which “sets the priest apart from the rest of the faithful” (MD, 43). He even goes so far as to say that the laity “can in no way possess sacerdotal power” (MD, 84) as does the ordained priest because they are not mediators between themselves and God (MD, 84). But Pius XII’s understanding of the Mystical Body means that he asked the faithful to understand that “to participate in the eucharistic sacrifice is their chief duty and supreme dignity,” urging them to be “united as closely as possible with the High Priest,” and in “union with Him…offer up themselves” (MD, 80). Though it is done “in a different sense” from the ordained priesthood, he notes, “it must be said that the faithful do offer the divine Victim” (MD, 85). Evidence for this claim was found in the “orate fratres” of the liturgy itself, where the priest asks the people to pray that “my sacrifice and yours may be acceptable” to the Father (MD, 87). By the waters of baptism, the people “are made members of the Mystical Body of Christ,” and “by the ‘character’ which is imprinted upon their souls” are “appointed to give worship to God. Thus they participate, according to their condition, in the priesthood of Christ” (MD, 88).

To participate in the eucharistic sacrifice is the laity’s chief duty and supreme dignity.

Pope Pius XII

Liturgical participation for the laity, then, is not only partaking in the external ceremonies of the rite, but in offering the “oblation” in which “Christ is made present upon the altar in the state of a victim” together with the earthly priest, and through him, Christ the High Priest (MD, 92). And to make this offering most effective, that is, to best participate in the sacrifice of Christ, Pius XII notes that the lay faithful should include “the offering of themselves as a victim” (MD, 98).

Through external participation in the rites and free internal participation in the oblation of Christ, the laity do more than simply wait for the priest to confect the Eucharist with powers they do not have. Rather, they participate in the action of Christ externally through the liturgical rites, and internally by exercising the powers and duties of their baptismal priesthood. The phrase “active participation,” then, takes on layers of nuance frequently forgotten in the years that followed Pius XII’s encyclicals. And the goal was much more than generating feelings of hospitality and inclusion. Rather, it was to act with Christ and as Christ, with the goal of participating in God’s own divine nature (MD, 155).

Vatican II in a New Light

When seen in light of Pius XII’s encyclicals, the Second Vatican Council’s Sacrosanctum Concilium (SC) and Lumen Gentium stand out as a great clarion call for the laity’s participation in the victimhood of Christ by virtue of their membership in the Mystical Body. Indeed, Lumen Gentium’s very chapter entitled “The People of God” claims that this people “has for its head Christ” (LG, 9) and then discourses on the hierarchical nature of the Church, noting that the ministerial priesthood and common priesthood differ “in essence and not only in degree” (LG, 10). As in Pius XII’s writings, the lay faithful are said to “join in the offering of the Eucharist by virtue of their royal priesthood” and are “consecrated by baptismal character to the exercise of the cult of the Christian religion” (LG, 10). Moreover, lay participation in the “Eucharistic Sacrifice” is to “offer the divine Victim to God, and offer themselves along with it” (LG, 10). One could say, then, that the People of God are gathered by the Lord precisely so that they may assemble as the Mystical Body and act as Christ, offering themselves together with the Immaculate Victim to die and rise again with him.

Sacrosanctum Concilium confirms and develops the idea that the sacred liturgy is not as an action of the People of God per se but is an action of Christ exercising his priestly office.

Sacrosanctum Concilium confirms and develops this idea, clearly defining the sacred liturgy not as an action of the People of God per se, but as an action of Christ exercising his priestly office (SC, 7). And since Christ’s nature includes his Mystical Body, consequently “in the liturgy full public worship is performed by the Mystical Body of Jesus Christ, that is, by the Head and His members” (SC, 7). Now the subsequent claims of the document become clear. Mother Church desires “that the faithful be led to that full, conscious and active participation in liturgical celebrations” precisely so that they may share in the action of Christ.

Since this is God’s chosen method to sanctify his people, their participation in the liturgy is, both obviously and profoundly, “the aim to be considered before all else” (SC, 14). Participation in liturgy is participation in Christ’s own perfect self-offering, and because the laity are members of Christ’s Mystical Body, they can be offered to the Father as a perfect offering as well. And sharing sacramentally in this seamless sacrifice, they are made holy as Christ is holy and, by extension, become perfect as their heavenly Father is perfect.

Sacrosanctum Concilium called for reforms which allow the corporate and sacrificial nature of the liturgy to shine refulgently so that the Mystical Body may act most perfectly. Rubrics were to take the role of the people into account (SC, 31). The rites were asked to shine forth without harmful accretions, or as the Council called it, with a “noble simplicity” (SC, 34, 48). Increased familiarity with scripture and liturgy-based homilies (SC, 35) were requested to increase people’s capacity to enter into the sacrifice. Even questions regarding the use of vernacular languages (SC, 36) and adaptations to the “genius and traditions of peoples” (SC, 37-40) were meant to allow the realities of the liturgy to penetrate the minds and heart of the faithful, making them participants rather than “strangers or silent spectators” (SC, 48).

By exercising their newly-discovered dignity as members of the Mystical Body of Christ, they would participate in Christ’s own action “by offering the Immaculate Victim, not only through the hands of the priest, but also with him…[and] offer themselves, too” (SC, 48). With a careful reform of the liturgy, the document implies, the People of God would not be inertly gathered like a pious crowd of individuals, but act as a Mystical Body. As Lumen Gentium notes, “it pleased God to bring men together as a people” (LG, 9), but this gathering was not an end in itself. Rather, it was a preparation for the “new and perfect covenant, which was to be ratified in Christ,” making humanity a “royal priesthood” (LG, 9) which could then offer true and acceptable sacrifice when united to the headship of Christ.

Vatican II hoped to transform the world by strengthening the Church grace, the Christ-life which would make human-life ever more divine.

Denis McNamara

Vatican II hoped to transform the world by strengthening the Church grace, the Christ-life which would make human-life ever more divine. The fountain of this Christ-life, of course, was the sacred liturgy, and self-offering as a member of Christ’s Mystical Body joined to Christ’s self-offering was the recommended remedy for this great need for divinization. Without an understanding of Mystical Body theology before the Council, the laity were often compared to deer yearning for running streams of Christ’s own life. It seems reasonable to ask, a half century after the Council, if the same can be said of great portions of the laity today. The rich theology of participation is laid like a feast in Vatican II, but it would not be hard to argue that in people’s lived experience of worship, it frequently suffers under the weight of liturgical trivialities and poor catechesis.

God’s goal is clear; he desires to share his own divine life with his creatures so that he might “be all in all” (SC, 48; 1 Cor 15:28). All he asks is that his people exercise the very “exalted nobility” which Pius XII proclaimed and surrender to his merciful love in the liturgy offered by the Church he gave us. Here is the clarion call to a new liturgical evangelization. Here is the true hope of Vatican II.

[1] Avery Dulles, SJ, in “Introduction to Lumen Gentium,” Walter M. Abbott and Joseph Gallagher, The Documents of Vatican II (Chicago: Association Press, 1966), page 12.

[2]Walter M. Abbott and Joseph Gallagher, The Documents of Vatican II, Lumen Gentium, footnote 27, page 24.

[3] Richard McBrien, “Vatican II Themes: The People of God,” National Catholic Reporter, July 25, 2011. Accessed July 28, 2020: https://www.ncronline.org/blogs/essays-theology/vatican-ii-themes-people-god

[4] The theology of the Mystical Body finds its foundation in the writings of St. Paul, especially Colossians 1:18 (“He is head of the body, the Church”) and Romans 12:4-8 (“For as in one body we have many members, and all the members do not have the same function, so we, though many, are one body in Christ, and individually members one of another.”)

[5] Though Pius X’s 1903 motu proprio Tra le sollecitudini is widely known as a foundational document for modern liturgical reform because it was the first papal document to use the phrase “active participation,” its emphasis proved largely on the externals of ritual worship and only implicitly acknowledged the liturgical assembly as a Mystical Body. He hoped that the restoration of chant would allow the faithful to “again take a more active part in the ecclesiastical offices, as was the case in ancient times” without specifically commenting on the nature of the laity’s liturgical participation.

[6] The bibliography of the Mystical Body before Vatican II is vast and was foundational in many areas including religious life, liturgy, social reconstruction and race relations. Romano Guardini’s The Spirit of the Liturgy addressed the notion of corporate worship in chapter 2, “The Fellowship of the Liturgy” as early as 1918. Influential also is Emile Mersch’s, 1938 book The Whole Christ: The Historical Development of the Doctrine of the Mystical Body in Scripture and Tradtion and the popularizing writing of Fulton Sheen through his 1934 book The Mystical Body. For a more recent work on the topic, see Timothy Gabrieli, One in Christ: Virgil Michel, Louis-Marie Chauvet and Mystical Body Theology (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2017).