“The post-conciliar era has scarcely been a period of undisturbed harmony and tranquility in regard to the way Catholics worship. On the contrary: it seems probable that the last thirty years have been the most liturgically troubled period since at least the era of the Reformation—now nearly half a millennium ago.”

With these words, part of a front-page analysis on the current state of the liturgy in the Church, Adoremus Bulletin officially launched into the deep and often troubled waters of liturgical reform.

Since that time, Adoremus has, according to its founders, become a byword for liturgical wisdom among many Catholics in the pews, rectories, and seminaries across the English-speaking Catholic world.

The first two eight-page issues of Adoremus were published in November 1995 and December 1995; today, Adoremus has expanded to a 12-page format and publishes every other month. Yet the heart of the publication’s mission, as reflected in its name (the Latin call to prayer: “Let us adore”), remains the same: to help bring Catholics to greater holiness through the liturgy.

Adoremus was founded by three people—two priests and a laywoman: Jesuit Father Joseph Fessio, who also founded Ignatius Press in 1976; Father Jerry Pokorsky, co-founder of CREDO, a society of priests committed to promoting a faithful translation of the liturgy; and writer, editor, and passionate Catholic activist, Helen Hull Hitchcock, founder of Women of Faith and Family (WFF). Together, they offered the faithful a periodical that would provide timely and truthful information and analysis on all aspects of the liturgy, seeking to show how the liturgical reform called for by the Second Vatican Council to the Church’s sacred body of communal prayer not only responds to contemporary needs but also finds its roots buried deep in tradition.

The history of Adoremus Bulletin begins not with its first issue in November 1995, however, but in June 1995. At that time, Fathers Fessio and Pokorsky and Mrs. Hitchcock (as she preferred to be known) founded the Adoremus Society for the Renewal of the Sacred Liturgy which, as the masthead of the Bulletin states, “was established…to promote authentic reform of the Liturgy of the Roman Rite in accordance with the Second Vatican Council’s decree on the liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium.” To help execute this mission, Adoremus Bulletin has served as the public face of the Society.

Sadly, Mrs. Hitchcock died in 2014, but to mark her lasting contributions to the success of Adoremus, her name remains on the masthead as a member of Adoremus’s executive committee. The other members of the committee, Fathers Fessio and Pokorsky, and long-time Adoremus contributor and research editor, Susan Benofy, recently spoke with Adoremus about how the paper came to be and how it flourished under Mrs. Hitchcock’s expert guidance as its editor. They also spoke about the significant progress in the Church regarding the liturgy over the last 25 years, and explained why Adoremus needs to continue to share the truth who is Jesus Christ especially as he is encountered in the liturgy.

Troubled Waters

It is perhaps no accident that Adoremus first began publishing in the month and year that the Novus Ordo was itself celebrating 25 years as the liturgy most familiar to the Western Church. Adoremus was founded to promote authentic Catholic liturgy—and its contributors found their work cut out for them in the problems associated with the new Mass.

Promulgated on November 30, 1969, the Mass of Paul VI had begun to stumble almost from the moment it came out of the gate. By 1995, that shaky start had become a crisis for many Catholics who, knowing the liturgy had better to offer than what they were witnessing in their own parishes, were searching for answers to many of the questions they had about the Church’s liturgy, and especially the greatest part of the liturgy, the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass.

As this writer had reported in a December 1 story about the 50th anniversary of the new Mass for the National Catholic Register, according to Monsignor Gerard O’Connor, director of the Office for Divine Worship for the Archdiocese of Portland, OR, and the author of The Archdiocesan Liturgical Handbook for Portland, the new Mass was received with mixed reviews:

“There were two sides to this story,” said Monsignor O’Connor in the Register story, regarding how the Mass was received among the faithful. “One side would say, ‘It was great.’” The other side was left confused, Msgr. O’Connor added, noting, “To a certain extent, what we did, dropping the Latin, turning the priest to face the people and using table altars instead of high altars, we certainly did look more Protestant than ever before, and that became a problem for some people.”

And it was a problem that Fathers Fessio and Pokorsky and Mrs. Hitchcock (with the support of her husband, renowned Catholic writer and historian, James Hitchcock) sought to remedy.

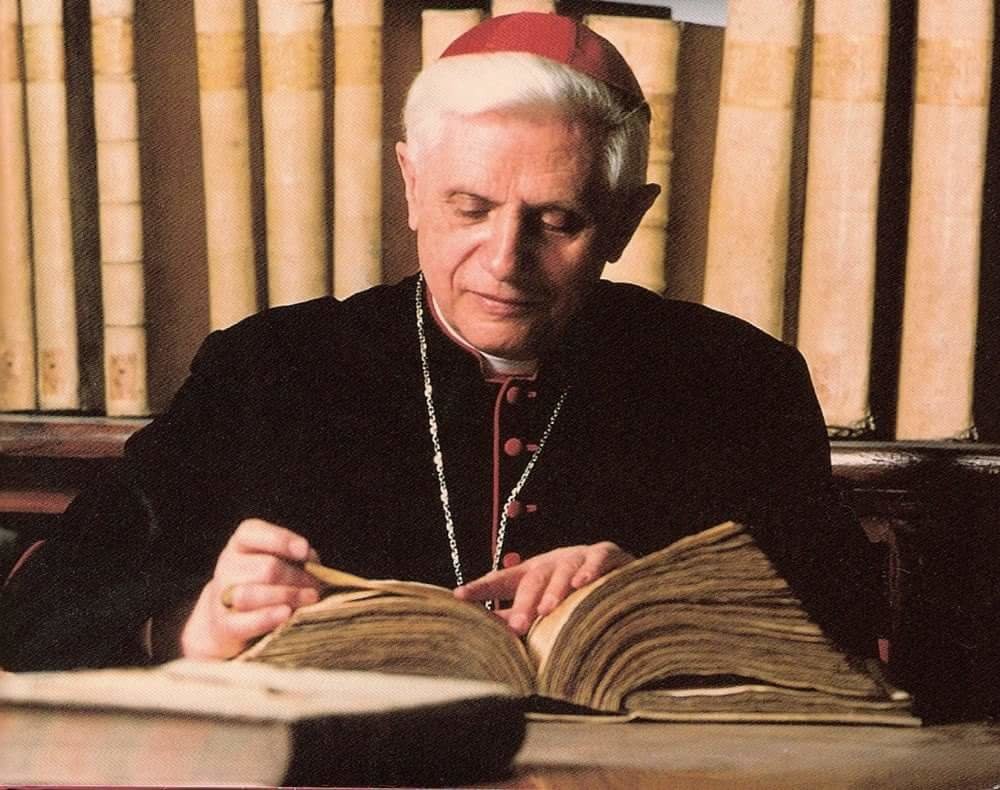

The inaugural November 1995 issue included a Q&A on the Society’s (and the Bulletin’s) purpose and goals, which quoted Pope Benedict XVI (at the time, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger) from his 1981 book Feast of Faith to explain its goals:

“Christian liturgy is cosmic liturgy, as Saint Paul tells us in the Letter to the Philippians,” Ratzinger writes. “It must never renounce this dignity, however attractive it may seem to work with small groups and construct homemade liturgies. What is exciting about Christian liturgy is that it lifts us up out of our narrow sphere and lets us share in the truth. The aim of all liturgical renewal must be to bring to light this liberating greatness.”

With Cardinal Ratzinger’s words serving as a guidepost to the strange land of liturgy run amuck, Adoremus sought to press the issue by helping the faithful see just how exciting the liturgy—as the Church intended it—could be.

Founded in Faith

According to Father Fessio, the idea for Adoremus took shape after a conversation he had with Cardinal Ratzinger, whom the Jesuit would visit once a year in Rome.

“It really crystalized for me during the time that Cardinal Ratzinger was writing his book, The Spirit of the Liturgy, from 1990 to 1999,” he said. During one of his visits with the cardinal, Father Fessio said, “I asked him what he was doing and he mentioned this book. Of course, it piqued my interest in what he was going to say in the book because he was a prelate with such a strong interest in the liturgy.”

After returning home and being further inspired by a presentation on the reform of the liturgy given at a conference in Colorado Springs, CO, by Father Brian Harrison, O.S.—the same presentation which would become in edited form the page-one article of Adoremus’s first issue—Father Fessio wrote a letter to Cardinal Ratzinger, dated April 19, 1995, “to ask your counsel on something which has been developing in my own mind for the past two or three years. Generally, it has to do with the reform of the Roman Liturgy, and more precisely with a ‘reform of the reform.’”

The Jesuit related to the cardinal how he had received “letters and phone calls from people who are distraught with the liturgies they are subjected to in their parishes,” but, he adds, they “are not just complaining about the state of the liturgy, but are asking what, if anything, can be done for the sake of future generations in the Church.”

In the same letter, he sketched out an idea for a liturgical journal of sorts which eventually emerged as the Adoremus Bulletin.

“One thought that occurred to me,” Father Fessio writes, “was that Ignatius Press might begin publishing a journal of liturgical renewal—not directed specifically at experts, but for all interested Catholics, without excluding specialists.”

More generally, Father Fessio sought Cardinal Ratzinger’s advice in his letter on whether it was appropriate to begin “a new liturgical movement,” but he was particularly interested in the cardinal’s opinion about a new publication dedicated to liturgical renewal. He was encouraged by its prospects, in part, because John Paul II had recently promulgated the Catechism of the Catholic Church, in 1992.

“Now that the Catechism is here, and with that as a base, I wonder if I should make a commitment of my own time and energy…towards promoting genuine liturgical renewal.”

According to Father Fessio, Cardinal Ratzinger’s response was both positive and encouraging.

Cardinal Ratzinger “wrote back a letter within a month,” Father Fessio told Adoremus, “and he said, basically, ‘Yes, I agree we need that kind of movement…and I think the time is ripe for the kind of journal you are describing.”

But if Father Fessio brought the idea for the project to the fore, he said that Father Pokorsky and Mrs. Hitchcock brought invaluable experience to make the project a success.

“You could say I was the pioneer and Father Pokorsky and Helen were the settlers!” he noted with a laugh.

Father Pokorsky’s work with CREDO—and his experience in business and finances prior to being ordained a priest—and Mrs. Hitchcock’s talent as a writer and editor provided Adoremus with its financial and editorial backbone. Both also had experience in liturgical matters.

“CREDO was a society of priests dedicated to the faithful translation of the liturgy,” Father Pokorsky said. “At the time, I coordinated the organization. We had over 2,000 priest members, and we advocated accurate liturgical translations and the recovery of the sacral vocabulary of the Mass.”

Likewise, he said, Mrs. Hitchcock founded WFF to “promote the authentic view of women in the Church and the culture. She was a fierce opponent of feminism and saw the ideological threat posed by so-called ‘inclusive language’ in the liturgy.”

Helen Hull Hitchcock

According to Benofy, Helen did not contribute only as an editor and writer; she wanted to use the Adoremus Society and its Bulletin as a way for the faithful to voice their concerns about the liturgy to their bishops.

“Helen was well aware that, although much could be done to encourage better celebrations by publications like Adoremus, any official revisions in the liturgical books depended on the Bishops’ Conference,” Benofy said. “So, in addition to publishing the Bulletin, [the Adoremus Society] supplied as much background information as possible on proposed innovations in the liturgy, translation, etc. to bishops who were trying to improve the proposed translation and adaptations. Helen called this ‘Holding up the arms of Moses.’”

According to Father Pokorsky, Mrs. Hitchcock also wanted the Adoremus Society to be a force for good among priests.

“Helen had an admirable and sincere respect for the priesthood,” he told Adoremus. “She also had a mature Catholic understanding of the distinction between the priests and laity. Helen truly wanted priests to understand their dignity as servants of the liturgy and mediators in Christ. But she would not be intimidated by the clericalism that presumed to violate liturgical norms for various purposes.”

Mrs. Hitchcock was well situated as Adoremus’s editor because of her talents and her passion for pursuing the truth and seeking to share it with others, said Father Fessio, adding that her base of operations was a sight to see.

The Hitchcocks “have a nice four-story house in St. Louis,” he said, “but in the basement, Helen and Jim had the most complete system of records on anyone of any importance in the U.S.” In her role as an activist in Catholic ecclesial politics, Father Fessio added, “she had documents, letters, articles, essays, reports on bishops and priests, and lay movements, and she was the repository of the most complete intelligence on the Church in the U.S. of anyone, I believe, in the whole country.”

“She did a yeoman ’s job in helping bishops who had questions, putting people in contact with each other, and being aware of things,” he added. “There wasn’t anything that happened that she didn’t know about.”

As editor and a writer for Adoremus, Father Pokorsky said, Mrs. Hitchcock produced news and analysis that was as impeccable as it was indisputable.

“If Helen wrote or reviewed it, fairness and accuracy were guaranteed,” he said. “She was uncommonly formidable, and I cannot remember a single instance where anybody challenged her facts.”

But even the greatest editors can make a slip of the blue pencil every now and then, Father Pokorsky added.

“I can think of only one mistake that got through under the radar,” he said. “But it wasn’t Helen’s fault. In email correspondence, she playfully identified the architect of a rather prominent Soviet-style, costly, church-related structure as ‘Hugh Cheatim Hall.’ (‘You cheated them all.’ Get it?) The typist didn’t recognize the joke, and we published the issue with the picture of the building with a humorous ID of the edifice. Helen (like all of us) thought the mistake was hilarious. But we received no complaints.”

Politics of Translation

If there was one central concern that Mrs. Hitchcock had while helming Adoremus, it was the question of an accurate and sacral translation of the liturgy into English. This concern began long before her involvement with Adoremus, though, said Father Pokorsky, noting that she served as editor of The Politics of Prayer (Ignatius Press, 1993), “a compendium of essays by various authors, describing the theological distortions inherent in imposing the feminist language on the sacred liturgy. It remains an essential historical record of the terms of the debate.”

But with Mrs. Hitchcock and her army of contributors itching for a fight, it wasn’t long before Adoremus entered the fray. For, while Adoremus sought to bring clarity to all aspects of the liturgy in the years after its founding, among the many challenges that the liturgy faced during those early years, Father Pokorsky told Adoremus, the “translation wars”—the struggle to produce an accurate and sacred English translation of the Mass—proved one of the most formidable.

“In the 1990s, we fought for an accurate translation more or less expecting to fail,” he said. “But we—or at least I—wanted to say to future generations, that at least we tried.”

According to Benofy, Mrs. Hitchcock worked tirelessly on the frontlines of that battle and she was among the first journalists in the U.S. to spread the word when the Vatican issued the 2001 document that many hoped would—and in fact did—resolve many of the issues surrounding the translation of the liturgy—the instruction Liturgiam Authenticam (“On the Use of Vernacular Languages in the Publication of the Books of the Roman Liturgy”).

“When Helen knew that Liturgiam Authenticam was due to be posted one night on the Vatican website, she stayed up checking the site until it was posted,” Benofy recalled. “Then she read the whole document and immediately wrote a commentary and posted it on the Adoremus website. She wanted a positive reaction to be available as soon as possible. And it was, as I recall, about the earliest commentary available.”

Less than three months after the instruction’s promulgation, on June 15, 2001, Adoremus ran an article on its website featuring responses from Catholic and secular news sources to Liturgiam Authenticam, prefaced by an unsigned editorial that Mrs. Hitchcock no doubt had a hand in crafting:

“Initial responses to the Holy See’s strong statement on liturgical translation were varied and revealing. Although Liturgiam Authenticam has been called a ‘victory for conservatives,’ this is not a political struggle for control (‘conservative’ Vatican vs. ‘liberal’ Bishops) as some insistently portray it. The comments that follow, gleaned from both secular and Catholic press accounts, though their viewpoints are diverse, reveal surprising agreement on the key importance of translation in the transmission of thought, of ideas. Lex orandi, lex credendi.”

“The dispute over translation is about ideas in this case,” the editorial continues, “the core teachings of the Catholic Church. Liturgiam Authenticam makes it clear that Scriptural and liturgical translations affect the very heart of the Catholic faith itself; and that the words used to express that faith matter deeply. What underlies the conflict over liturgical translation is, finally, authentic vs. inauthentic belief.”

According to Father Pokorsky, the instruction had a direct bearing on the 2010 revised translation of the Mass in English.

“In the early 1990s, liturgical authorities planned for the release of a new translation by 1995,” he said. “But the translation wars resulted in a 15-year delay. So the new English translation of the Latin typical edition (by a reformed ICEL) was promulgated in 2010. For the most part, the new translation was free from most of the ideological accretions the old ICEL proposed in the 1990s.”

While the victory ultimately belonged to God and his Church as a whole, Father Pokorsky sees that Adoremus’s part in ensuring proper translations of the liturgy shows that the publication has more than justified its existence.

“I’m pleasantly surprised we effectively won the translation wars,” he said. “The victory means that a few thoughtful, orthodox, and organized Catholics can be very effective in making positive contributions to the Church today.”

The Mission Continues

After Mrs. Hitchcock’s death in 2014, Adoremus’s executive committee tapped Christopher Carstens to take over the work begun 25 years ago. According to Father Pokorsky, the new blood at Adoremus is upholding the legacy that Mrs. Hitchcock left upon her death.

“Chris Carstens, the new editor, is doing a great job in keeping the body and soul of Adoremus together,” he said. “I particularly appreciate his ability to identify new young writers and expanding competent and orthodox interest in the liturgy.”

Today, the challenges facing the liturgy may be of a different sort, but Adoremus’s overall mission contributes to addressing those challenges, said Benofy.

“In essence, the needs are still the same: a reverent and beautiful liturgy,” she said. “Also proper liturgical catechesis so the people understand the purpose of the liturgy and why reverence and beauty are necessary.“

For a quarter of a century, Adoremus has been providing thoughtful and faithful reflection on the liturgy, and Father Fessio said there has been much progress in bringing about the restoration of the liturgy which the publication was founded to help achieve.

“In the last 25 years, there have been a lot of positive steps and improvement in the liturgy,” he said. “One reason for that is the ebullience for change—here, there, and everywhere—has died down. We also have a whole new generation of priests who are John Paul II and Benedict XVI priests, and—especially in the last 10 to 20 years—a large number are well versed in liturgy. We have bishops who are more liturgically oriented as well.”

The liturgy seems in much better shape today, Father Pokorsky acknowledged; yet, it is paramount that the faithful continue to learn about—and learn to love—the liturgy.

“There is a continuing need to rediscover the ‘spirit of the liturgy’ in every generation,” he said. “There is much work to be done, especially in the formation of seminarians who sometimes find it difficult to appreciate what a ‘normal’ liturgy means.”

“The laity also needs encouragement to ‘pray always and never lose heart,’” he added. “The Mass is the source and summit of our existence, for experts and non-experts alike.”

As for the original mission of Adoremus, begun with that first issue of November 1995, Father Fessio said, it hasn’t changed one iota from then to now.

“Until we really achieve what the Second Vatican Council intended,” Father Fessio said, “and we have a liturgy that is contemporary and sacred, rooted in tradition and fulfilling the fundamental desires of the Council, Adoremus Bulletin needs to continually work toward that end.”