How to Make Mass More Child-friendly by Re-introducing a Youthful Wonder into the Liturgy

I was with him, forming all things, and was delighted every day,

playing before him at all times, playing in the world,

and my delights were to be with the children of men.

–Proverbs 8:30-31

If you have children who squirm through Mass, who complain on Sunday morning, and make life miserable because they don’t want to go, you’re probably not alone. Mass at most parishes is not a child-friendly event. Priests are aware of the problem, and making Mass more appealing to children is a constant concern for us. Priests have been known to go to extremes, using props and interactive homilies in an attempt to engage young attention spans. I’ve seen it all—puppets that deliver homilies, hand-motions and dancing during songs, and an entire child-specific Eucharistic prayer. None of it works. Or if it does, what the children are learning is not to participate in Mass but to be satiated by what I would call Mass-adjacent entertainment. This is why I don’t use these methods.

We could give in and create a separate Sunday morning experience for the kids—that way the parents could drop their children off before Mass, pick them up after, and have no distractions during an adult-only Mass. Or we could compromise and section off the kids who are repeat offenders into a cry room. These approaches I find equally troublesome, though, because they miss the point of worshiping as a family. They reduce the diversity of the congregation, are prejudicial against a certain age group, and make it all the more challenging for the little ones to learn how to participate once the adults deem them to be ready.

If we want to find a solution for integrating children into the community, we would do far better to stop assuming that it is children who are the problem and take a hard look at ourselves. The problem isn’t the kids. It’s the adults. We have drained the Mass of its imagination and drama, creating a bland, highly intellectualized, auditory experience. Take, for instance, the secret but true motivation of priests: we want the children sent away so parishioners can hear the homily. I admit, there are times when I’m preaching and kids are rattling the very bones of the building with shrieks and cries. It also isn’t unusual to look up from my text mid-homily and observe no less than 50 parishioners staring at a smiling baby instead of paying attention to me. It can be challenging to preach to such a diverse, distractable crowd, but is it so bad? Is it so bad for me to be forced to be more concise during my homily instead of indulgently droning on at length? Further, is it so bad for children to squirm and wiggle through Mass, to hear their off-tune voices drown out everyone else during the Agnus Dei?

There’s a fine line between lawlessly out-of-control toddlers and children who are trying their best but still learning how to be fully present. But I think we more or less agree on where that line is and can extend a certain degree of trust and charity to the parents. If any of us adults are tempted to cast the first stone, perhaps we might recall the times our eyes have glazed over during Mass and we’ve failed to fully participate. Simply because our failures are quieter and more socially acceptable doesn’t mean we don’t struggle with the same issue that the children do. In the meantime, there are, in fact, concrete and simple ways to make Mass more child-friendly in a way that also promotes reverential worship.

Just Imagine

First, we must understand the type of language the Mass is actually speaking. Worship isn’t an intellectual exercise. The purpose of Mass isn’t purely catechetical, the homily is not meant to be a lecture, and even us adults don’t know the full meaning of every action. The impulse of the priest to halt and explain every action or to delete any ritual that isn’t entirely clear is a symptom of the misunderstanding concerning the true language of worship. It’s perfectly acceptable to not understand everything happening at Mass. In fact, a bit of mystification is to be expected because the language of the Mass isn’t prose—it’s poetry. The Mass is a poem, and it uses the language of imagination and hope.

Who speaks this type of imaginative language on a regular basis? Children. In Spirit of the Liturgy, Romano Guardini indicates as much, writing, “The liturgy gives a thousand strict and careful directions on the quality of the language, gestures, colors, garments and instruments which it employs,” and it can only “be understood by those who are able to take art and play seriously.” When he refers to “play,” Guardini means an activity that is undertaken for its own sake with no further motives. It is children who naturally take this type of activity seriously. They spend vast quantities of their day in the world of imagination and play. They speak the language of poetry, which Aristotle teaches is a communication of what might be and what ought to be.

Each action of the Mass is a mediation of the heavenly reality, the ways in which God and Man are connected by Jacob’s Ladder as angels ascend and descend upon it. The air itself is thronged with saints, members of the Church triumphant who pray with us. The priest stands in place of our Great High Priest, Jesus Christ, and sends up an offering to our Heavenly Father, who in turn sends down his blessing upon our sacrificial gifts. This is the poetic, symbolic, and quite seriously playful language of the Mass. It’s a discussion in which children are uniquely qualified to participate.

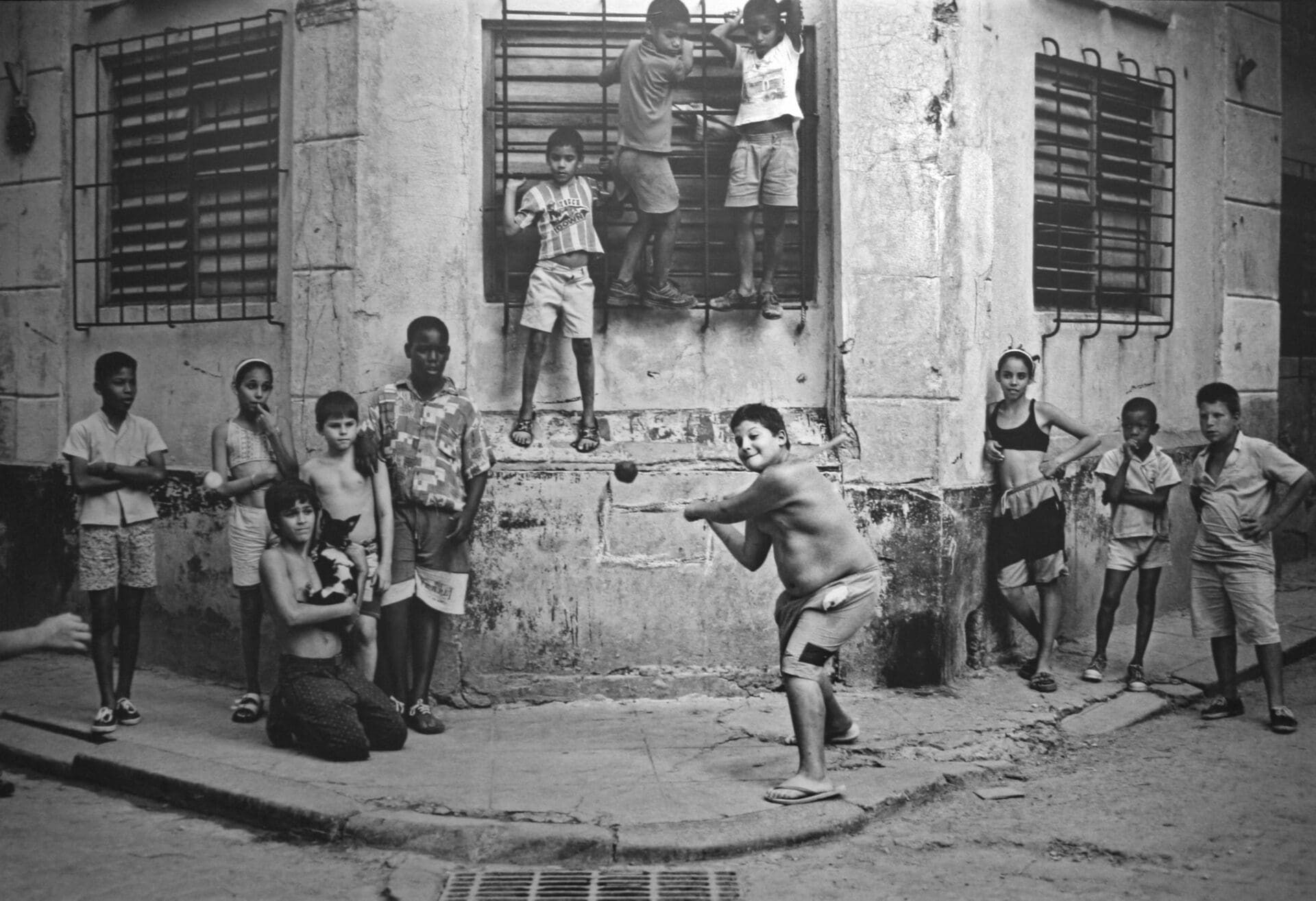

When I was a child, my friends and I would play baseball in the park behind my house. There weren’t enough of us to field complete teams of nine, so we created a strike zone by taping a square on the tennis court fence. We designated a stand of pine trees about two-hundred feet away as the home run marker, created complicated rules about how runners would advance, how outs would be marked, and how hits would be measured. Having our rules delineated, we were ready to play. The first pitch arrived at home plate. And then we argued. Was it a ball or strike? Did it hit inside the square or not? Did the hit transgress the imaginary foul line? Our obviously partisan eyes deceived us, and the seriousness of the game required an extended disputation until finally a compromise would be negotiated. Then the next pitch would arrive and we would do it all over again.

Play It Up

I tell this story from my youth to say that children are serious about playing. Their games seem unimportant but they are earnest. Grave and dour adults may disapprove and, like the adults in Antoine St. Exupery’s The Little Prince, they may attempt to force children to address themselves to more practical pursuits such as balancing account books or counting their possessions. An analogue to the Mass might be the insistence that everything be highly orderly, efficient, and practical. Fancy vestments must be thrown out, the sanctuary simplified, and the shortest, simplest, vernacular prayers pressed into service. But as St. Exupery indicates, this denies a fundamental fact of our existence; the ability to look deeply and see the hidden truth of God’s sacramental presence.

The inability to view the world as a child limits us to observing only the outer, physical shell. It misses the miraculous reality within. What is invisible to the eye is most important, but without the imagination of a child we are unable to see it. When this happens, the Mass becomes a shadow of itself as the focus turns away from its symbolic heart. It’s a patrimony squandered, a revolt of fathers against their very own children. Perhaps this is why Our Lord is so insistent that his apostles, later to become the first spiritual fathers of the Church, freely bring the little children into his presence. It’s a reminder we desperately need.

It is, in fact, the children who do the apostles the favor. It is the children who lead the adults back to Our Lord and reveal to them the language of wonder. In the prayers at the foot of the altar in the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite, it is made abundantly clear that it is still the children who lead their priests to the place of worship. The priest pauses, and after acknowledging the Triune God, the first words out of his mouth are, “Introibo ad altare dei/ I will go unto the altar of God,” to which his server responds, “Ad Deum qui laetificat juventutem meum/ To God who giveth joy to my youth.” The priest, as he steps up to the altar to offer the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, does so with childlike wonder.

Wonder, says Socrates, is the beginning of wisdom. It is not immature or unsophisticated for us to speak the language of children, and a reverent Mass won’t dispense with their presence. In fact, the presence of children at Mass is of great assistance to us jaded adults, and the only conclusion I can reach is that children are not only to be tolerated at Mass, but they are to be positively encouraged to participate because they lead us to Our Lord.

Children of Men

But children still need to be integrated into the community in such a way that they play by the rules. To that end, there are a number of ways to make a Mass more child-friendly. I have implemented a number of these in my parish and the result has been a noticeable increase in the number of children in our parish. I know a number of other priests who have done the same with similar results.

Minimize Cry Rooms

If children are having trouble sitting still, it may be as simple as the fact that they cannot see what’s happening. I encourage young children to sit as close as possible. Even better, I encourage our children to jump into the thick of the action by becoming altar servers as soon as they can. There is no age minimum. Even if they’re simply standing next to the older children while wearing cassock and surplice, the responsibility is invigorating. All of this is lost in a cry room, which often feels like sitting in a fishbowl. Cry rooms are only for screaming infants.

Maximize Incense

Use generous amounts of incense and use it often. Mass should appeal to all five senses, including smell. Children are quite impressed with the effect of incense and the way it wafts up to heaven. The smell of it creates a strong association in the memory. Best of all, for the altar boys, it adds a strong element of danger (Matches! Charcoal! Fire!)—and responsibility.

Utilize Plainchant

Plainchant is easy to teach to children and it requires very little music theory. Mostly it’s an understanding of relationships between notes that are sung with the fluidity of the way we would naturally speak. Teaching children to chant, especially the young children who cannot read, is a much more effective way to draw them into active participation in worship than hymns, which are difficult for children to read along with and sing.

Catechize the Tongue

When the language we use to describe something doesn’t match the reality, children immediately notice the disconnect. If I teach that the Blessed Sacrament is a precious treasure to be treated with reverential care but then behave in a casual fashion with it, children lose interest. They sense the falsehood and realize the adults aren’t as serious as they claim. I encourage all our parish children to receive on the tongue. We also use communion patens and I do the ablutions carefully and prayerfully at the altar. Bringing our actions in line with our words brings credibility to the Mass and keeps children interested.

Emphasize Processions

Children love processions. Processions are physical, impressive, and imaginative. Processions for Palm Sunday, to bury the Alleluia in the front garden, the Vidi Aquam, and getting out a canopy to march down the street while chanting the Pange Lingua for Corpus Christi: all of this speaks to the sensibilities of children.

Colorize Devotions

Colorful and vivid images, like music, serve as a universal language—and no less so for children—and no less so in liturgical and devotional life. Celebrate a May Crowning and have the children bring flowers from the garden at home, veil statues in Passiontide, burn palms after Mass to get ready for Lent. We recently restored the devotion of veiling our statues and the children all had questions. One child asked, “Why is Jesus hiding?” Intuitively, the child had caught onto the precise meaning of the veiling.

The Joy of Youth

Making a Mass child-friendly is actually fairly easy, and it’s all right there in our Catholic heritage. Give children a Mass that is serious but playful, imaginative and impressive, full of life and color, dangerous and mysterious, and they will absolutely fall in love. They’ll go home and make their own vestments and have processions at home and play Mass with every snack you give them.

Speak to them in the language of poetry, of heaven, and open up for them greater vistas within which they can dream. Not only will your Mass become more child-friendly, it will also be of great benefit to us adults as we do our earnest best to approach the altar with the joy of our youth.