Considering that so much of the debate about liturgy today is concerned with the rite of Mass itself—Ordinary vs. Extraordinary form, or the merits of proposed changes in the rite—the following statement from a book by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI) may be surprising: “The crisis in liturgy (and hence in the Church) in which we find ourselves has very little to do with the change from the old to the new liturgical books.… [T]here is a profound disagreement about the very nature of the liturgical celebration…. The basic concepts of the new view are creativity, freedom, celebration and community.”[1]

Possibly more surprising is that proponents of the “new view” make similar statements. For example, liturgist Ralph Keifer said, “Considered from the perspective of the official texts, liturgical reform has meant only a modest revision of the Roman rite mass.… Yet this modest change of ceremony has helped to precipitate a revolution in our ritual.”[2]

But if changes in the rite did not cause the “revolution,” what did? In his remarks to the Roman Curia in 2005, Pope Benedict XVI spoke of larger interpretive conflicts concerning the Second Vatican Council. “The problems in its implementation,” he said, “arose from the fact that two contrary hermeneutics came face to face and quarreled with each other. One caused confusion, the other, silently but more and more visibly, bore and is bearing fruit.” The first, a “hermeneutic of discontinuity and rupture” saw sharp contrasts between the tradition and the post-conciliar Church, invoking a so-called “spirit of the Council” divorced from the actual texts of the Council. The second hermeneutic, one of “reform and renewal,” read the conciliar texts and the post-conciliar reform in continuity with what came before, even while adapting ecclesial life, when and where possible, to modern conditions.

The liturgy—in its practice, its theology, and its spirit—similarly succumbed to battling hermeneutics. Changes wrought in the liturgy came about through a divergence in focus on what the liturgy essentially is. Two predominant views of the liturgy emerged after the Council, and it is this divergence which has created the unhealthy tension that the faithful experience in “liturgical politics” even today. The first of these views, which is more sympathetic to tradition, holds that there is an objective pattern of worship which all liturgy embraces. The second is more subjective and holds that the liturgy is most perfectly realized when tailored to the communal experience of worship. Benedict and Kiefer both see the “spirit of liturgy”—be it objective or subjective—as the starting point of post-conciliar renewal. To appreciate the quarrelling “spirits of the liturgy,” and to appreciate what the Council Fathers themselves held it to be, we need not go back far in Church history to see that the objective view is the correct view.

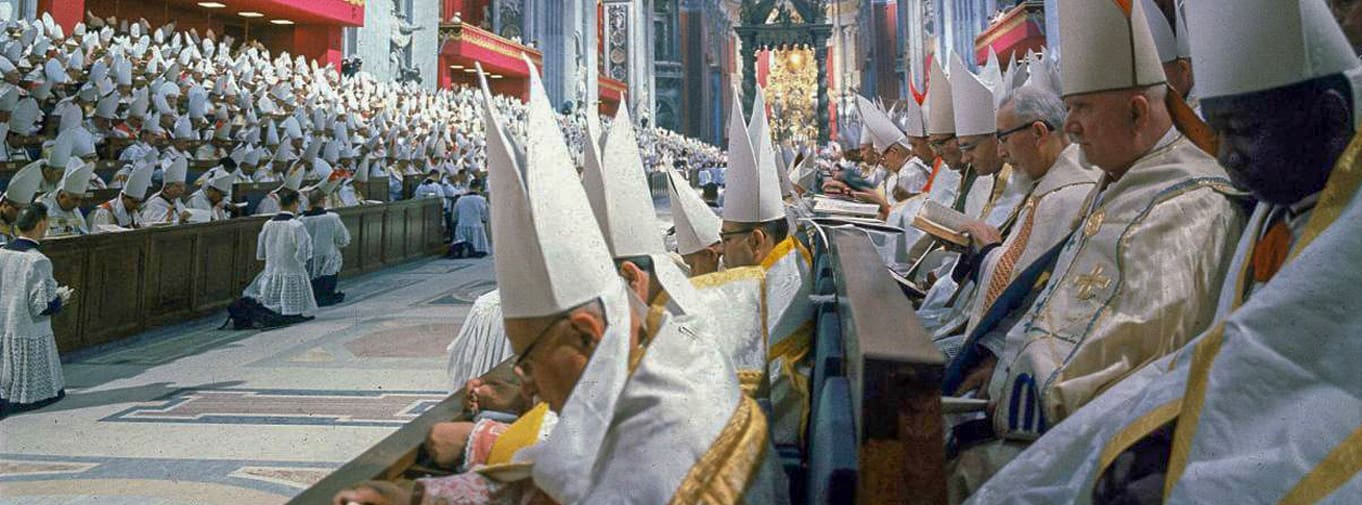

Texts of the Council

Consider what the Council itself, in its Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy (Sacrosanctum Concilium (SC)), saw as crucial to liturgical reform: “In the restoration and promotion of the sacred liturgy, this full and active participation by all the people is the aim to be considered before all else; for it is the primary and indispensable source from which the faithful are to derive the true Christian spirit…. Yet it would be futile to entertain any hopes of realizing this unless the pastors themselves, in the first place, become thoroughly imbued with the spirit and power of the liturgy, and undertake to give instruction about it” (SC, 14).

Though the earlier parts of paragraph 14 are quoted in virtually every discussion of liturgical reform, the second sentence above is rarely cited, even though the Constitution is quite emphatic here.

The Council did not give specific details about what constituted this true “spirit of the liturgy.” The phrase had appeared in Pope Pius XI’s 1928 apostolic constitution Divini Cultus and in Pope Pius XII’s 1948 encyclical letter Mediator Dei. The expression also brings to mind two books of that title. The more recent, a 2000 book by Cardinal Ratzinger,[3] was inspired by Romano Guardini’s 1918 book of the same name.[4] Ratzinger says that Guardini’s book The Spirit of the Liturgy “inaugurated the Liturgical Movement in Germany. Its contribution was decisive. It helped us to rediscover the liturgy in all its beauty…and time-transcending grandeur…as the prayer of the Church, …guided by the Holy Spirit himself….” [5]

Since it is generally agreed that the Liturgical Movement, in turn, influenced the Council’s reform of the liturgy, it seems reasonable to take Guardini’s 1918 book as a guide to the spirit of the liturgy that Sacrosanctum Concilium considered so crucial.

Objective Spirit

Guardini lays great stress on the slow development of the liturgy through time. Though influenced by a variety of cultures, it does not reflect any single one, but “is the supreme example of an objectively established rule of spiritual life.” Furthermore, he states, “The primary and exclusive aim of the liturgy is not the expression of the individual’s reverence and worship of God…. In the liturgy God is to be honored by the body of the faithful…. It is important that this objective nature of the liturgy should be fully understood.”[6] As a consequence of this objectivity, the liturgy “is a school of religious training and development to the Catholic who rightly understands it.”[7]

However, Guardini also says, the liturgy is difficult to adapt to modern man, who often finds it artificial and too formal, and prefers other forms of prayer which seem to have the advantage “of contemporary, or, at any rate, of congenial origin.”[8] But to be appropriate as a prayer for all people, and any situation, the liturgy must be formal, and keep “emotion under the strictest control.”[9]

The direct expression of emotion in prayer is more appropriate in personal prayer or popular devotions. These are rightly intended to appeal to certain tastes and circumstances, and consequently retain more local characteristics and aim more at individual edification, but they must remain distinct from the liturgy. “There could be no greater mistake than that of discarding the valuable elements in the spiritual life of the people for the sake of the liturgy, or than the desire of assimilating them to it.”[10] The liturgy is celebrated by the whole body of the faithful, not simply the assembled congregation. It embraces “all the faithful on earth; simultaneously it reaches beyond the bounds of time.”[11]

Guardini notes that, since the liturgy doesn’t fit any personality type exactly, all must sacrifice some of their own inclinations to properly enter into it. And, though liturgy requires fellowship, this does not mean ordinary social interaction. “[T]he union of the members is not directly accomplished from man to man. It is accomplished by and in their joint aim, goal, and spiritual resting place—God—by their identical creed, sacrifice and sacraments.”[12] Guardini insists that liturgical prayer “must spring from the fullness of truth. It is only truth—or dogma, to give it its other name—which can make prayer efficacious.”[13]

Revolutionary Spirit

Now consider how the “revolution” in the liturgy was brought about. According to Keifer: “The real revolution was that the agents of reform…effectively abolished the distinction between sanctuary and nave.”[14] They relocated “the place of the holy in the midst of the assembly,”[15] placing the people—not God—at the center of the liturgy, and shifting the focus of prayer. Kiefer claims that “liturgical prayer is not simply speech in common addressed to God. Rather it is speech to one another addressed in God’s ‘overhearing.’”[16]

Who were these “agents of reform” Keifer mentions? Many were speakers and writers, associated with liturgical publications and organizations, especially the Liturgical Conference. This organization was very influential around the time of the Council through its publications, annual conferences (called Liturgical Weeks) and numerous workshops.[17] A series of books, The Parish Worship Program,[18] was planned the very week that Sacrosanctum Concilium was approved by the Council, and according to its then-president, Father Gerard Sloyan, the series was designed to communicate the change in spirit that he believed was the most important impending change in the liturgy. Two prominent members of the Liturgical Conference were Father (later Monsignor) Frederick McManus, who served several terms as its president, and Father Godfrey Diekmann, OSB (of St. John’s Abbey in Collegeville, MN), a member of the Conference’s board and a frequent speaker at Liturgical Weeks.[19] They gave many talks on Sacrosanctum Concilium, especially for priests, between sessions of the Council.[20] Others considered in this article include Clement McNaspy, SJ, another board member of the Liturgical Conference, and Father Robert Hovda of Fargo, ND, editor of its publications from 1965–1978.[21] The contrast between this “new spirit” expressed in their work and Guardini’s is striking.

One revolutionary change in spirit is already evident in a 1963 book of essays, Sunday Morning Crisis: Renewal in Catholic Worship, which proclaimed on its cover: “Here, for the first time, is what liturgical renewal means to you.”[22] In his Introduction, Father Hovda asserts, like Kiefer, that liturgy is primarily communal and only secondarily a matter of the worship owed to God: “[I]t is through relating to one another before God…that Christians properly worship and accomplish the proper purpose of worship. The following essays hope to help make that relating a matter of common Sunday morning experience.”[23]

Likewise, McManus, in his essay in this volume,[24] claims that during the first session of Vatican II the Council Fathers approved a liturgical reform based on three principles: the communal nature of the liturgy, its pastoral purpose, and its adaptability. (Note how closely these correspond to Cardinal Ratzinger’s description of the “new view.”) The pastoral purpose, McManus says, means that changes in the liturgy will be dictated by the needs of the people, and can no longer conform to a universal pattern which looks first to the proper objective worship of God. Therefore, since there is a great diversity of cultures in the world, the liturgy “must match this diversity and be open, always open, to change and growth…. Times and customs change, so must the ways of worship.”[25]

But the emphasis on direct communication between people “radically localizes the liturgy,” as Keifer pointed out. Local languages and styles of music replace worldwide use of Latin and Gregorian chant, for example. “This contributes effectively to a fading of the Roman, and hence, the papal image that the liturgy once carried. This is the reason why appeals to outside authority about details of practice are experienced as so incongruous and inappropriate now.”[26]

In addition, this emphasis on the local produces the very situation Guardini warned against: the loss of the necessary distinction between liturgy and devotions. In fact, contrary to Sacrosanctum Concilium,[27] these liturgists scorned devotions, anticipating their disappearance. Even Eucharistic devotion will decline, McManus predicts in an essay in the 1963 volume The Revival of the Liturgy: “with the devotion of the people now directed to the eucharistic meal, the accidentals in the Eucharistic cult outside Mass will not flourish so widely.”[28]

In contrast to the gradual development of the liturgy in the past, and ignoring the Council’s call for “careful investigation into each part of the liturgy which is to be revised” (SC, 23), these liturgists were in a great hurry to implement their views. In fact, McManus insists that “progressives” must not compromise but “must take more advanced positions from the beginning…to leave room for concession or bargain.”[29] “If too little is sought or attempted, doors now open may be shut.”[30]

Premature Interpretation

Both Sunday Morning Crisis and The Revival of the Liturgy have imprimaturs dating from the summer of 1963, before the second session of Vatican II had even begun. So these essays interpreted Sacrosanctum Concilium before it was eventually promulgated on December 4, 1963, or even fully discussed at the Council. Implementing “advanced positions” arguably changed people’s experience of the liturgy (as the liturgists intended) more than the changes actually authorized by Sacrosanctum Concilium and the earliest implementing documents. Directing the focus of the liturgy to the assembly, they tended to desacralize the liturgy.

In a 1964 essay, Father McNaspy notes that all known religions distinguish between the sacred and the profane. The sacred is “apart, separate…. The holy is what one does not touch, does not discuss, often…does not even pronounce.”[31] But since in modern times we stress rationality over mystery, he cautions against “too casual an acceptance of the terms ‘sacral’ or ‘holy’”[32] and rejects the traditional forms that express it. For example, Romanesque and Gothic architecture and Gregorian chant are, he admits, “apart” today. But instead of considering these ancient forms, as Guardini does, to be part of a gradually developing objective pattern, McNaspy associates them exclusively with the past and believes their use today is actually a danger: “Does it not suggest that religion is simply quaint, archaic, and irrelevant?”[33]

Diekmann also rejects traditional forms of architecture in an essay on this subject. Although not published until 1965, it is clear from the text that the essay was written before September 1964 in anticipation of the Vatican instructions on the arrangement of churches found in Inter Oecumenici. Diekmann even admits that it may seem premature to offer details, as he does, before the official document is promulgated. But he believes his procedure is justified since he intends simply to “draw what seem reasonable deductions from the altiora principia (“higher principles”) contained in the Constitution.”[34] He argues that ecclesia, meaning church, was first applied exclusively to the assembly, and only later to the church building: “The ecclesia, as worshiping People of God, most effectively manifesting the infinite mystery of the Church, ranks among the altiora principia of the Constitution.”[35] From this he concludes that the primary purpose of a church building is to facilitate the “common experience of community.”[36]

Consequently, he insists that churches must not be “grandiose ‘monuments to God’s glory,’”[37] but rather designed so that each person can experience “a meaningful function in the common action. This would unquestionably rule out the long rectangle, the one shape of a church that has been most customary.”[38]

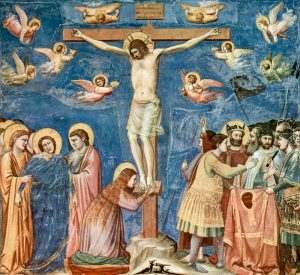

He also interprets a second higher principle—emphasis on the paschal mysteries—as requiring personal and communal experience. This can be facilitated, he suggests, by a standing posture after the Consecration and during the reception of Holy Communion. Since he believes that the Communion rail “has come to connote…a wall of separation from the sanctuary,” he recommends distribution to standing communicants at Communion “stations” as “paradoxically, both more reverent and swift.”[39] He also believes the altar should be free-standing with the priest facing the people. Visually obstructive objects, including the crucifix, should be removed. As to other images, he tells us: “it may be ‘the better part’ for the present to be prudently and orthodoxally iconoclastic.”[40]

The Vatican’s Instruction, entitled Inter Oecumenici, when it was promulgated on September 26, 1964, lacked many of the provisions Diekmann anticipated. It did provide that the main altar “should preferably be free-standing to permit celebration facing the people” (§ 91, emphasis added). But it spoke of the “cross and candlesticks required on the altar” (§ 94, emphasis added). It said nothing about removing the Communion rail, standing for Holy Communion, or the need for the church building to facilitate the experience of community.

Even though Deikmann’s 1964 predictions so often went beyond, or even contradicted the subsequently released Inter Oecumenici, McManus praised Diekmann’s essay in a 1965 address to 500 architects and church building commission members. Diekmann was writing before the promulgation of the 1964 Instruction, McManus said, but added that “it is valid now and will be as valuable in the future. The meaning of norms must be sought in the supporting reasons, for which we must look to the commentators.”[41] While the Instruction’s norms may seem legalistic, McManus said, they allow “for the greatest creativity,” aim “to restore the meaning of the Eucharist as community action,” and recognize that “there should be diversity, adaptation to local circumstances and occasions.”[42] That is, he insists this Instruction supports the “new view.”

Liturgical Changes

Inter Oecumenici also included some changes in the rite of Mass. Among the most obvious were permission for vernacular recitation (or singing) of most prayers said by the people and priest (together or in dialog) and the new formula for distributing Holy Communion (Corpus Christi). A few of the prayers said by the priest—formerly said in silence—were to be said aloud, and readings were proclaimed in the vernacular at a lectern facing the people. Laymen could read those scriptural selections before the priest proclaimed the Gospel. Some texts from the Mass were altogether omitted, such as Psalm 42 (from the Prayers at the Foot of the Altar), the Last Gospel (John 1:1-14) and the Leonine prayers recited after Mass by priest and people. There also were a few ceremonial changes concerning the sung Mass and incense.

In the U.S. the instruction was implemented on November 29, 1964,[43] and that implementation should have entailed only the changes in the rite mentioned above. However, the optional practice of celebrating Mass facing the people also became almost universal.The addition of receiving Communion standing, the removal of Communion rails and statues, as well as the singing of four vernacular hymns (none of which were even mentioned by the Council or the instruction) tended to convey the “new spirit” and made the experience seem more like a “new liturgy.”

The hymn-singing, however, was a continuation of a preconciliar practice which permitted hymns in the vernacular during a low (read) Mass.[45] The low Mass was the most common form before the Council, and often preferred by influential liturgists for its “flexibility.” The pattern of four hymns at low Mass was promoted particularly by the Liturgical Conference in the 1950’s,[46] and their influential Parish Worship Program[47] recommended this as the preferred form of Mass after the Council. So, though singing by the people was emphasized and occurred at almost all Masses after the Council, the sung (high) Mass, which required the singing of liturgical texts themselves, virtually disappeared.[48]

At first the hymns were fairly traditional, but soon they were replaced by a secular style of music. This development was promoted by Diekmann in an address to the annual convention of the National Catholic Education Association (NCEA) in April 1965. According to press reports Diekmann “spelled out the task of teaching the Mass to students through participation geared to their way of communicating with each other.”[49] Asking how teachers could help the Mass become “subjectively, in the thinking and living of our pupils…, the fount of all holiness…?” he answered: “Quite frankly, I wish I knew.”[50] Yet he does not hesitate to make concrete suggestions.

Diekmann seems most concerned that students, allegedly impatient with formality, are bored at Mass, which Sacrosanctum Concilium calls a “celebration.” This word choice, he says, means it should be a “shared festivity” so he suggests that the “experiment and variety” allowed by the “new liturgy” be used to make the student Mass a “lived faith experience” and a “meaningful pleasure to be looked forward to.” Contrary to Guardini’s thoughts on the matter, Diekmann does not suggest that students learn to see the Mass as a “school of religious training,” as Guardini explicitly says,[51] nor that they be instructed in the Church’s heritage of sacred music. Instead students must have maximum input on the details of the Mass, including the music. He anticipates the sort of music the students will request, asking, “Are we perhaps sinning against our high-schoolers, depriving them of lawful celebration which, according to their culture…would foster faith, if we exclude folk song [and] spirituals—or ‘Kum ‘ba Ya’”?[52] He implicitly answers in the affirmative by proposing what he calls the “hootenanny Mass” for student liturgies in high schools.

The audience of 3,000 Catholic educators, it was reported, responded to this talk with “thunderous applause.”[53]

That’s All Folk!

Another enthusiast for the folk Mass, Ken Canedo, in his history Keep the Fire Burning,[54] traces the early development of liturgical “folk” music by Catholic composers (often seminarians) and the spread of this music (and the idea of congregational input) as it replaced more traditional hymns in schools and colleges throughout the country. This early folk-style music is often rightly criticized for its poor quality,[55] but rarely mentioned is the additional problem of the attitude and the “spirit” it introduced into the Mass.

Canedo notes that in the early twentieth century “folk music took root in the cities as a medium of radical thought.” Some folk singers wrote original songs in folk style, which “directly challenged the establishment.” This eventually “blossomed into the protest-laden radicalism” of the 1960’s.[56] Consequently, Canedo writes, the folk Mass “sometimes became a worshipful act of defiance in dioceses that banned it.”[57]

But the “establishment” being defied here was legitimate Church authority, and the defiance soon extended beyond worship. On January 31, 1966, the New York Times reported: “A group of University of Detroit students demonstrated yesterday in front of the Archdiocese of Detroit chancery against a ban of a folk-music-style Mass.… Some 50 students marched in freezing weather in front of the Chancery, carrying a sign: ‘We want our Mass.’”[58]

This music (and the “new spirit”) soon spread to parishes. Instead of the promised experience of community, however, it resulted in the division of the parish into factions, each saying, in effect: “We want our Mass.”

Sense and Sentimentality

Guardini, decades before, had warned against these very approaches to the liturgy. Diekmann contended that liturgical participation would be enhanced by adaptations intended to increase personal pleasure. But Guardini considers this “sentimentality,” i.e., “the desire to be moved,” as an obstacle to participation. Adapting the Mass to the congregation’s tastes blocks participation because the form of the Mass is “that which obedience to the Lord’s command has received from His Church.… He who really wishes to believe—in other words, to obey revelation—must obey also in this, schooling his private sentiments on that norm.”[59]

Furthermore, Guardini warned that when a believer is no longer concerned with fundamental principles, but only with his own personal faith experience, “the one solid and recognizable fact is no longer a body of dogma…but the right action as a proof of the right spirit.… Religion becomes increasingly turned towards the world, and cheerfully secular.”[60] Soon dogma itself became a matter of protest, most prominently in the reaction to Humanae Vitae in 1968.

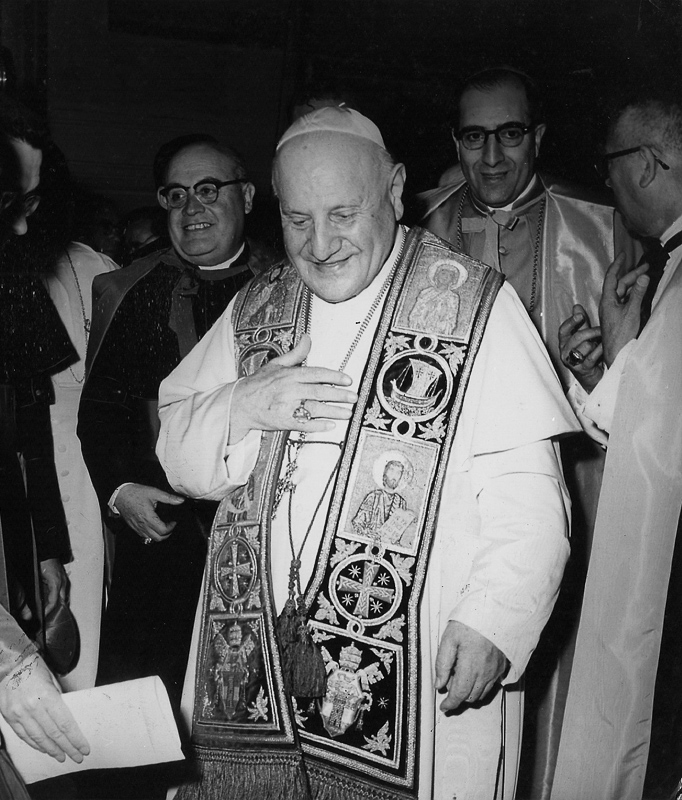

The Council and earlier Liturgical Movement intended something very different from what the “new view” had in mind. On December 25, 1961, Pope John XXIII officially convoked the Second Vatican Council with the Apostolic Constitution Humanae Salutis, in which he expressed the hope that the Council “imbues with Christian light and penetrates with fervent spiritual energy not only into the depths of souls but also into the whole realm of human activities.” Similarly, 25 years earlier, the American liturgical pioneer Virgil Michel, OSB expected that a Christian who “drinks deep at the liturgical sources of the Christ-life,” would “spare no effort to Christianize his environment,” resulting in “a true reflourishing of Christian culture, of the arts and literature, of social institutions formed after the mind of Christ.”[61]

But today, as Cardinal Gerhard Müller, former Prefect of the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith, has recognized: “We are experiencing conversion to the world, instead of to God.”[62] Why? Recall that the Council itself told us that it “would be futile to entertain any hopes of realizing” the goal of active participation and liturgical renewal unless priests and people were first “thoroughly imbued with the spirit and power of the liturgy” (SC, 14).

Spirit of the Liturgy Revisited

By the end of 1965, years before the Novus Ordo Missae was promulgated, only a few changes had been mandated for the rite itself. Yet the introduction of other practices not mentioned in Sacrosanctum Concilium had already changed people’s experience of the liturgy. They were designed to imbue priests and people with a “new spirit,” contrary to the one Guardini had proposed. Fifty years later the liturgical reform has not reached its goal, and we experience ever more strongly what Cardinal Ratzinger called “the crisis in liturgy (and hence in the Church).” This suggests that the new spirit was not what Sacrosanctum Concilium 14 meant.

Re-examining post-conciliar liturgical practices, guided by Guardini and Sacrosanctum Concilium, would perhaps allow today’s Catholics to become imbued with the true spirit of the liturgy as the Council urged. Eliminating those practices not in accord with Sacrosanctum Concilium and this spirit could help people to experience a time-transcending, beautiful liturgy as well as congregational unity which is not merely social but “is accomplished by and in their joint aim, goal, and spiritual resting place—God—by their identical creed, sacrifice and sacraments.”[63] And it would no longer be futile to hope, with Pope John XXIII, that through the restored liturgy fervent spiritual energy would penetrate souls, and lead to the transformation of the whole realm of human activities.

[1] Joseph Ratzinger, Feast of Faith: Approaches to a Theology of Liturgy, trans. Graham Harrison, (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1980), 61.

[2] Ralph A. Keifer, The Mass in Time of Doubt: the Meaning of the Mass for Catholics Today (Washington, DC: National Association of Pastoral Musicians, 1983), 56. Keifer was professor of liturgy at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago, acting executive secretary (1972-1973) and general editor (1971-1973) of the International Commission on English in the Liturgy (ICEL).

[3] Joseph Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy, trans. John Saward, (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2000).

[4] Page references for Guardini in this paper refer to a reprint edition combining two of Guardini’s books: The Church and the Catholic and The Spirit of the Liturgy, trans. Ada Lane, (New York: Sheed and Ward, Inc, 1953).

[5] Ratzinger, Spirit of the Liturgy, 7.

[6] Guardini, Spirit of the Liturgy, 121-122.

[7] Ibid., 155.

[8] Ibid., 156.

[9] Ibid., 129.

[10] Ibid., 123.

[11] Ibid., 141.

[12] Ibid., 147.

[13] Ibid., 126.

[14] Keifer, The Mass in Time of Doubt, 56.

[15] Ibid., 65.

[16] Ibid., 87.

[17] For more on the Liturgical Conference see Susan Benofy, “The Day the Mass Changed–Part I,” Adoremus Bulletin, February 2010. A very large number of people participated in the workshops. In Chicago alone “an initial six-week training program for commentators, lectors and leaders of song involved no less than 11,400 laymen.” See Godfrey Diekmann, “Liturgical Practice in the United States and Canada” in Consilium: The Church Worships, Vol. 12 (1966), 157-166, quotation on 164.

[18] These books were said to be “the first and for a long time the only aids made available to guide the celebration in the new rites.” See Gordon E. Truitt, “Gerard Sloyan: Bridge of the Spirit” in How Firm a Foundation: Leaders of the Liturgical Movement, compiled and introduced by Robert L. Tuzik (Chicago: Liturgy Training publications, 1990), 222-299. See especially 295.

[19] Both served as liturgical periti (experts) at Vatican II, and long-term members of the ICEL Advisory Committee. McManus was also the first director of the Secretariat of the Bishops’ Committee on the Liturgy (1965–1975).

[20] In a letter to J. B. O’Connell dated March 3, 1964, Diekmann wrote: “Fred [McManus] and I have been very busy lecturing to groups of priests throughout the country ever since returning from Rome. And the list of such engagements stretches through the next months, until September. Actually, it has been very edifying to discover how willing, and even eager, priests of advanced years are to listen and to learn. If only we can reach enough of them.” Quoted in Kathleen Hughes, RSCJ, The Monk’s Tale: A Biography of Godfrey Diekmann, OSB (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1991), 252.

[21] Hovda was also principal author of the U.S. Bishops’ Committee on the Liturgy 1978 statement “Environment and Art and in Catholic Worship.” McNaspy was a musicologist and an editor of the Jesuit magazine America.

[22] Sunday Morning Crisis: Renewal in Catholic Worship, (Baltimore: Helicon Press, 1963), ed. Robert Hovda (imprimatur dated July 17, 1963).

[23] Robert Hovda, “Introduction” in Sunday Morning Crisis, 4 (original emphasis).

[24] Frederick McManus, “What is Being Done?” in Sunday Morning Crisis, 45-58.

[25] Ibid., 55.

[26] Keifer, Mass in Time of Doubt, 60.

[27] “Popular devotions of the Christian people are to be highly commended, provided they accord with the laws and norms of the Church…. But these devotions should be so drawn up that they harmonize with the liturgical seasons, accord with the Sacred Liturgy, are in some fashion derived from it, and lead the people to it….”

[28] Frederick McManus, “The Future: Its Hope and Difficulties,” in The Revival of the Liturgy, ed. Frederick R. McManus (New York: Herder and Herder, 1963), 203-224 (imprimatur August 8, 1963) Cited passage, 209.

[29] Ibid., 212-213.

[30] Ibid., 218. Yet as late as 2004, McManus, though regretting that recent Vatican documents had narrowed “the openness of the great council to adaptation and inculturation,” still asserted “no door has been closed.” See Pastoral Music. October-November 2004, 45-47.

[31] Clement J. McNaspy, SJ, “The Sacral in Liturgical Music,” in The Revival of the Liturgy, 163-190. See particularly, 166.

[32] Ibid., 167.

[33] Ibid., 178.

[34] Godfrey Diekmann, OSB, “The Place of Liturgical Worship” in The Church and the Liturgy in Consilium: Church and the Liturgy, vol. 2 (1965), 67-107. See particularly 68. He does not specify where in SC he finds these higher principles. If, in fact, the suggestions he makes in this essay depend on SC it is odd that they were already featured in a church built in the 1950’s: the Abbey Church of St. John’s, which Diekmann helped to plan. See Hughes, Monk’s Tale, 169-175.

[35] Ibid., 73-74.

[36] Ibid., 75.

[37] Ibid., 76.

[38] Ibid., 85.

[39] Ibid., 98.

[40] Ibid., 105.

[41] Frederick McManus, “Recent Documents on Church Architecture” in Church Architecture: The Shape of Reform: Proceedings of a Meeting on Church Architecture Conducted by The Liturgical Conference February 23-25, 1965, in Cleveland Ohio (Washington, DC: The Liturgical Conference, 1965), 86-95. Cited passage, 87.

[42] Ibid., 94-95.

[43] Not only was this interval between promulgation and implementation (September 26-November 29) quite short, but the bishops, who were to direct this implementation, were absent from their dioceses for most of it. They were in Rome attending the third session of the Council, which ran almost exactly concurrent with this interval – from September 14 to November 21.

[44] In most places this involved an arrangement not apparently envisioned by the 1964 Instruction: placing a new table-style altar in the sanctuary in front of the old main altar. Since the new altar could appear insignificant contrasted with the older abandoned, but more impressive, main altar this could seem to diminish the significance of the Mass.

[45] See the 1958 Instruction from the Sacred Congregation for Rites, De musica sacra et sacra liturgia §14b.

[46] See Eugene A. Walsh, SS, “Making Active Participation Come to Life” in People’s Participation and Holy Week: 17th North American Liturgical Week (Elsberry, MO: The Liturgical Conference, 1957), 45-63.

[47] See the volume in this program: A Manual for Church Musicians (Washington, DC: The Liturgical Conference, 1964), especially 47-50. See also, Susan Benofy, “The Day the Mass Changed–Part II” in Adoremus Bulletin, March 2010.

[48] There was, in fact, an obstacle to having a sung Mass with English liturgical texts at this time. Melodies for texts to be sung by the priest or ministers required approval from the conference of bishops (See Inter Oecumenici §42). Yet it was not until November 17, 1965, that the U.S. Bishops’ Conference approved such settings, which could not be used until March 27, 1966. (See Thirty-Five Years of the BCL Newsletter 1965-2000, (Washington, DC: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2004), 34.

[49] See, for example, in the diocesan paper of the Archdiocese of Indianapolis: “‘Hootenanny Mass’ defended by liturgist,” The Criterion, May 14, 1965, 7.

[50] “Liturgical Renewal and the Student Mass,” (An address delivered at the 62nd annual NCEA Convention, April 19-22, 1965) Bulletin: National Catholic Education Association 62, #1 (August 1965), 290-300. See particularly 295.

[51] Guardini, Spirit of the Liturgy, 155

[52]Diekmann “Liturgical Renewal and the Student Mass,” 297.

[53] See “‘Hootenanny Mass’ defended by liturgist,” The Criterion, May 14, 1965, 7. About the same time Father McNaspy promoted the ‘folk Mass’ for college students. See “America editor defends ‘folk Mass’” on the same page.

[54] Ken Canedo, Keep the Fire Burning: The Folk Mass Revolution, (Portland, OR: Pastoral Press, 2009). There are podcasts which summarize the book and give samples of the compositions in it at https://kencanedo.com/podcasts Canedo is currently a liturgical composer and music development specialist at Oregon Catholic Press.

[55] Yet it was performed at Carnegie Hall. Canedo explains that McNaspy organized a concert of Liturgical “folk” music at this venue “to introduce to the public the new musical innovations going on in the Church at the time.” Keep the Fire Burning, 81. A live recording was made of this concert and released on LP. Some tracks from this recording can be heard on Canedo’s podcast “Chapter 9B.”

[56] Canedo, Keep the Fire Burning, 18-19.

[57] Ibid., 72.

[58] Ibid., 71, citing a New York Times article from Feb 1, 1966, “Detroit U Students Protest Ban of Folk-Music Mass.”

[59] Romano Guardini, Meditations Before Mass. (Manchester, NH: Sophia Institute Press, 2013), 101.

[60] Guardini, Spirit of the Liturgy, 205.

[61] Virgil Michel, OSB, “The Scope of the Liturgical Movement,” Orate Fratres (Worship) 10 (1935-36), 485-490. See particularly 488. Michel was a monk of St. John’s Abbey in Collegeville, MN and the first editor of Orate Fratres.

[62] Cardinal Gerhardt Müller in Catholic World Report www.catholicworldreport.com/2018/06/26/

[63] Guardini, Spirit of the Liturgy, 147.