Ubi caritas gaudet, ibi est festivitas.

“Where love rejoices, there is festivity.”

–St. John Chrysostom[1]

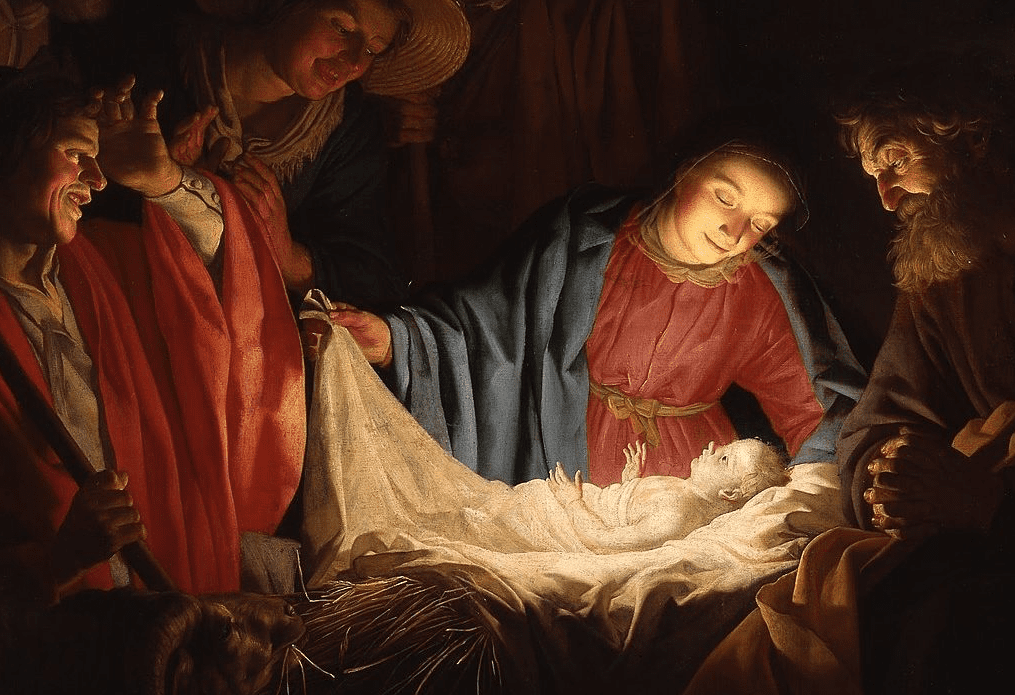

Even in the cold winter snow, the Nativity of the Lord invites us to bask in the glory of the “grace of God [that] has appeared” (Titus 2:11). For, it is in this cradle of redeeming love that we see Love Himself rejoicing…and so are “caught up through him in love of things invisible” (Preface, Christmas I).

Of this day one author wrote, “When we say, ‘It is Christmas,’ we mean that God has spoken into the world his last, his deepest, his most beautiful word in the incarnate Word…And this word means: I love you, you, the world and humankind.” Yet, more than just speaking love, this Word is Love. The Solemn Festival of Christmas is a festive-rejoicing that Love himself has entered the world through the flesh of his mother, Mary. It is a festive-rejoicing that Love himself comes alongside us not to just tell us, but to show us that Love is real and true and beautiful. It is a festive-rejoicing because we are not simply shown this Love, but he himself is present to us and dwells within us.

In a Land of Gloom, Love?

Yet, it is hardly self-evident that love is the meaning of life, that love is the origin from which man buds forth and the end toward which creation is tending. The universe seems to teach otherwise: galaxies grow further apart; emptiness fills the universe; our Sun will stop shining; the earth is growing old; resources are dwindling; people go hungry, starve; addiction runs rampant; murder; rape; slavery; abortion; hatred; violence. Every one of us is dying. But we’ve experienced love, haven’t we?

In the face of such evil, how can we believe in the love we think we’ve seen? In his play, The Jeweler’s Shop, Pope St. John Paul II has an exasperated Adam exclaim to Anna, who has lost any sense of love in her marriage, “Ah, Anna, how am I to prove to you that on the other side of all those loves that fill our lives—there is Love?” (64). How, indeed? The Collect for the Fourth Sunday of Advent makes this clear:

Pour forth, we beseech you, O Lord,

your grace into our hearts,

that we, to whom the Incarnation of Christ your Son

was made known by the message of an Angel,

may by his Passion and Cross

be brought to the glory of his Resurrection.

It is the “Passion and Cross” of the Incarnate Son that bring us to the “glory of his Resurrection.” In this way, the fullness of the mystery of Christ is invoked to show forth the “love of things invisible” (Preface, Christmas I). Indeed, the “grace sought [in this collect] is not simply the grace that attaches in a limited way to the incarnation,” but the grace obtained “through the passion and cross of Christ to the glory of resurrection—not to the Pasch [only] but to the vision of the resurrected Christ and, ultimately, to the resurrection of our own bodies.”[2]

The Cross at Christmas?

At this point we might object, “Why think about the Cross and such ugliness at Christmas?” Yet, Christmas is not the antithesis of the Cross, but rather the first manifestation of the Love poured out on the Cross. Jesus is conceived in circumstances that raised moral eyebrows; born in poverty, in the dirtiness and filth of the stable; placed in a common animal trough; greeted by the shepherds who were considered among the most untrustworthy and dirtiest individuals of the region; visited by the magi, essentially pagan idolaters; cut by the knife of circumcision; and hunted mercilessly by the territorial sovereign.

Love on the Cross makes clear the Love in the cradle: in the cross, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ resounds the proclamation that death, destruction, betrayal, and hatred are all spineless nothingness. Love has triumphed through the Cross in His resurrection! And this is a love that doesn’t stand aloof from suffering or settle for niceties, fluffiness, or cotton ball sentimentality. Rather, this Jesus who is Love enters into the very depths of evil in all its horror. Only in the light of the resurrection of the Crucified One does the light of Christmas fully shine forth and its meaning become clear. As the Collect for Mass During the Night reads:

O God, who have made this most sacred night

radiant with the splendor of the true light,

grant, we pray, that we, who have known the mysteries of his light on earth,

may also delight in his gladness in heaven.

And the Light Shines in the Darkness

Indeed, it is only in the midst of that first-century “land of gloom” (Isaiah 9:2) and with eyes of faith that the beauty, the glory, the festivity of Love Himself rejoicing in the arms of Mary and Joseph come to light. And mankind rejoices in seeing his day because “many prophets and righteous men longed to see what [we] see, and did not see it, and to hear what [we] hear, and did not hear it” (Mt. 13:17). It is here in the Holy Mass that we see the Word made flesh come to dwell among us and where he himself rejoices to be lovingly received into our bodies in the Holy Eucharist. Yes, “Where love rejoices, there [indeed] is festivity.”

Jeremy J. Priest is the Director of the Office of Worship for the Catholic Diocese of Lansing, MI, as well as Content Editor for Adoremus. He holds a Licentiate in Sacred Theology (STL) from the Liturgical Institute of the University of St. Mary of the Lake, Mundelein, IL. He and his wife Genevieve have three children and live in Lansing, Michigan.

Notes:

[1] John Chrysostom, De Sancta Pentecoste, hom. Migne, PL 50, 455. Cited in Josef Pieper, In Tune with the World: A Theory of Festivity (South Bend, IN: St. Augustine’s Press, 1999), 23. Many of St. John Chrysostom’s homilies have been preserved through Latin translation. See Sever J. Voicu, “John Chrysostom (Latin Collection),” ed. Angelo Di Berardino and James Hoover, trans. Joseph T. Papa, Erik A. Koenke, and Eric E. Hewett, Encyclopedia of Ancient Christianity (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic; InterVarsity Press, 2014), 2:434.

[2] Lauren Pristas, The Collects of the Roman Missals: A Comparative Study of the Sundays in Proper Seasons before and after the Second Vatican Council (London: T&T Clark, 2013), 55.