The bishop’s role in the liturgical life of the particular Church[1] over which he presides can be considered from three angles: 1) the liturgical life of the Church as the source of his own personal sanctification, 2) his role as chief priest and celebrant of the sacred mysteries entrusted to his stewardship, and 3) his pastoral role in promoting and regulating the Church’s public worship among that portion of the People of God entrusted to his care.

It’s Personal

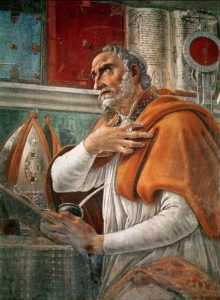

In an oft-quoted passage, St. Augustine once said to the people of the particular Church of Hippo, “For you I am a bishop, with you I am a Christian,”[2] indicating that what he shares first and foremost with the faithful is the spiritual blessings Christ communicates to us through his Church: faith, sacraments, and a grace-filled life. Within his own soul the bishop must live the spiritual life that is made possible through the Church’s corporate worship. Now more than ever, we are acutely aware of how the pastor must first be a faithful disciple before he can begin to lead and form those brothers and sisters in the faith the Lord has given him. The words spoken to blessed Peter also apply to the bishop: “I have prayed that your own faith may not fail; and once you have turned back, strengthen your brothers.”[3] So the bishop’s personal spiritual life must find its own source and summit in the Church’s sacred rites.

In his 2003 Apostolic Exhortation Pastores gregis, St. John Paul II stated that just as the paschal mystery of the Lord’s death and resurrection stood at the very heart of his mission on earth, so the sacramental celebration of that mystery should form the heart and center of the bishop’s life and mission—as it should for every priest.[4] The Holy Father recommended the daily celebration of Mass by the bishop. This counsel, of course, is an explicit application to the bishop of what the Code of Canon Law recommends for every priest: “Remembering always that in the mystery of the Eucharistic sacrifice the work of redemption is exercised continually, priests [sacerdotes] are to celebrate frequently; indeed, daily celebration is recommended earnestly since, even if the faithful cannot be present, it is the act of Christ and the Church in which priests fulfill their principal function.” [5]

Moreover, the bishop is urged to cultivate a love of the Holy Eucharist by devoting a “fair part of his time” [satis longum tempus] during the day to adoration before the tabernacle. In this way he allows his heart to be molded by the Good Shepherd, who laid down his life for the sheep, and he can make constant intercession for his sheep.[6]

The second element of the bishop’s liturgical spirituality is the celebration of the Liturgy of the Hours. This duty, first accepted when he was ordained a deacon, acquires particular force when carried out as an intercession for the flock entrusted to his care. In fact, before the imposition of hands in the rite of episcopal ordination, the candidate is asked: “Do you resolve to pray without ceasing to almighty God for the holy people of God and to carry out the office of High Priest without reproach?”[7] This prayer for his people must become an essential element of his own spiritual life. In this way he will be seen both as a teacher of prayer and as one who promotes prayer by his personal example.

Since it is the bishop’s duty to invite all to conversion and repentance and to point out the destructive presence of sin in personal and social life, the sacrament of Penance must hold a special place in his spiritual life. In order to be an effective minister of the work of reconciliation, “he himself will have a regular and faithful recourse to that sacrament.”[8] He does so not only to set an example to the faithful, but because of his own human frailty:

“Mindful, therefore, of his human weaknesses and sins, each Bishop, along with his priests, personally experiences the sacrament of Reconciliation as a profound need and as a grace to be received ever anew, and thus renews his own commitment to holiness in the exercise of his ministry. In this way he also gives visible expression to the mystery of a Church which is constitutively holy, yet also made up of sinners in need of forgiveness.”[9] Now more than ever, it is important for bishops to acknowledge publicly that they, too, are sinners in need of forgiveness.

The personal spirituality of the bishop includes much more than the points mentioned above. The essential liturgical elements of his spiritual life, though, must be the daily celebration of Mass, Eucharistic adoration, daily celebration of the Liturgy of the Hours, and frequent recourse to the sacrament of Penance. Nemo dat quod non habet (“No one gives what he doesn’t have”), says the Scholastic maxim, so the bishop must have a true liturgical piety if he is to lead his people in the Church’s life of grace.

Mystery Man

One of the distinguishing marks of the last ecumenical council was the attention it paid to developing a fuller theological understanding of the bishop’s pastoral office in the Church. Most of chapter three (about four-fifths) of the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church is devoted to the nature and ministry of the episcopacy in the Church, which is also the subject of an entire document, the Decree on the Pastoral Office of Bishops in the Church.[10] What emerges from these conciliar teachings is the bishop’s distinctive role of acting in the person of Christ as High Priest.

“In the person of the bishops…, the Lord Jesus Christ, supreme High Priest, is present in the midst of the faithful.… [I]t is above all through their signal service that he preaches the Word of God to all peoples and administers without ceasing to the faithful the sacraments of faith.”[11] This exercise of the supreme priesthood is carried out “above all in the Eucharist, which he himself offers, or ensures that it is offered,”[12] since “the Church draws her life from the Eucharist,”[13] which is “the source and summit of the Christian life.”[14]

This high priestly function is seen most clearly when the whole People of God of a particular Church gather around their bishop in his cathedral “in the same Eucharist, in a single prayer, at one altar at which the bishop presides, surrounded by his college of presbyters and his ministers.”[15] Church law takes this theological principle and translates it into specific obligations for every diocesan bishop: he is to celebrate Mass frequently in his cathedral or another church of his diocese, especially on holy days of obligation and other solemnities.

In addition, he is strictly obliged—even if he does not do so publicly—to celebrate and apply a Mass personally for his people on Sundays and on the holy days of obligation observed in his region. If he is legitimately impeded from fulfilling this duty of the Missa pro populo, he is either to apply the Mass on the same day through some other celebrant or to offer the Mass himself on another day.[16]

Since preaching is the pre-eminent function of the bishop[17] and the homily is an integral part of the liturgy, the bishop should see his Eucharistic homily as the “most excellent” of all forms of preaching. He “should seek to expound Catholic truth in its fullness, in simple, familiar language, suited to the capacities of his hearers, focusing—unless particular pastoral reasons suggest otherwise—on the text of the day’s liturgy. He should plan his homilies so as to elucidate the whole of Catholic truth.”[18] Effective preaching also includes the duty of personal integrity, for his teaching is prolonged by his own witness of an authentic life of faith. “Were he not to live what he teaches, he would be giving the community a contradictory message.”[19] No one today can fail to see the importance of that observation.

The bishop’s exercise of the munus sanctificandi extends to the other sacraments of the Church as well. As the chief steward of the divine mysteries, he has responsibility for the entire process of Christian initiation, for he regulates the celebration of Baptism and is the original minister of Confirmation.[20] In particular, his involvement in Christian initiation means that he should “celebrate its principal steps. And he should exercise his ministry in the sacraments of initiation for both adults and children at the solemn celebration of the Easter Vigil and, as far as possible, during pastoral visitations.”[21]

It is also his responsibility to regulate and promote the pastoral formation of catechumens, as well as to celebrate the rite of election if possible.[22] Moreover, the Baptism of adults who have completed their fourteenth year is to be referred to the bishop, so that he himself may confer it if he judges it appropriate.[23] As a matter of practice, though, the bishop often does not reserve the Baptism of adults to himself but directs that the sacrament be celebrated in the parish where the catechumen resides.

On the other hand, the Confirmation of those previously baptized in the Catholic Church (usually in infancy) is to be administered by the diocesan bishop himself or he is to ensure that it is administered by another bishop. Priests may be granted the faculty (required for validity) only in cases of necessity.[24]

Among the bishop’s many tasks, great care should be given to proclaiming the mystery of God’s boundless mercy and the gift of the Holy Spirit for the forgiveness of sins. This divine grace is made available especially in the sacrament of Penance, in which the faithful “obtain from God’s mercy pardon for the offense committed against him, and are, at the same time, reconciled with the Church which they have wounded by their sins.”[25]

While the bishop should be an exemplary minister of the sacrament himself—St. John Paul II gave the Church a vivid image of that ministry by his personal example for many years—the bishop provides for the needs of his people particularly by exhorting “his priests to hold in high esteem the ministry of reconciliation which they received at their priestly ordination, and he should encourage them to exercise that ministry with generosity and supernatural tact,”[26] since the majority of the faithful receive the grace of this sacrament from the ministry of their priests. The bishop should also exercise vigilance in ensuring that the norms on general absolution are followed and remind his priests that “individual and integral confession and absolution constitute the only ordinary means by which members of the faithful conscious of grave sin are reconciled with God and with the Church.”[27]

Since Christ instituted in his Church a variety of ministries for the growth of God’s People and the good of the whole body, the bishop has the duty to provide ministers endowed with sacred power for the spiritual care of the flock entrusted to him. Thus his “ministry as both head and servant of the community of the faithful is exercised especially when he confers the Holy Orders of diaconate and priesthood.”[28] The ministry of ordination is reserved to a bishop, and each candidate to the priesthood or diaconate should be ordained by his proper bishop or with dimissorial letters authorizing another bishop to ordain him. So important is this ministry in the life of the particular Church, that the bishop is himself to ordain his own subjects unless he is impeded by a just cause. [29]

Temple Guard

Within the particular Church, primary responsibility for promoting and regulating the sacred liturgy belongs to the bishop as high priest of his people. The Second Vatican Council said that bishops are “the principal dispensers of the mysteries of God and are the moderators, promoters, and guardians of the liturgical life of the Churches entrusted to their care.”[30] Not only should the bishop be an exemplary celebrant of the liturgy, he must also promote the liturgical life of the Church by exercising his teaching office in such a way that his clergy and people have an ever fuller understanding of the Church’s worship. Thus he “should elucidate the inherent meaning of the rites and liturgical texts, and nourish the spirit of the liturgy in the priests, deacons and lay faithful.”[31]

No religious leader relishes the role of enforcer, yet in liturgical matters the bishop is obliged to “be vigilant that the norms established by legitimate authority are attentively observed.”[32] He should pay special attention to the general principle laid down in Sacrosanctum Concilium that no one, “even if he be a priest, may add, remove, or change anything in the liturgy on his own authority,”[33] since true liturgical worship can only be “offered in the name of the Church, by persons lawfully deputed, and through actions approved by ecclesiastical authority.”[34] A proper, dignified, and spiritually fruitful celebration of the Church’s worship must have the highest priority in the pastoral care of his flock.[35]

In addition to urging the observance of those liturgical laws established by higher authority, “it also belongs to the diocesan bishop, within the limits of his competence, to lay down liturgical regulations which are binding on all in the Church entrusted to his care.”[36] The various liturgical books and instructions from the Holy See spell out in greater detail what falls within the competence of the diocesan bishop, and there is an overview of his responsibilities in the Directory for the Pastoral Ministry of Bishops.[37]

At the same time, the bishop “must take care not to allow the removal of that liberty foreseen by the norms of the liturgical books so that the celebration may be adapted in an intelligent manner to the Church building, or to the group of the faithful who are present, or to particular pastoral circumstances.”[38] Thus, the bishop has authority to publish norms, for example, on concelebration, service at the altar, communion under both species, the construction and renovation of church buildings, posture, liturgical music, and days of prayer, but with the exception of those modifications assigned by law to the diocesan bishop, “no additional changes to liturgical law may be introduced to diocesan liturgical practice without the specific prior approval of the Holy See.”[39] Choices or options foreseen by liturgical law may be selected by the celebrant according to his prudent judgment, while variations not foreseen by the liturgical books may not be added on one’s own authority.

Pray, Protect, Promote

The bishop’s lofty calling to act in the person of the Christ, the High Priest, must be reflected in his own life of liturgical prayer, in the way he celebrates the Church’s sacred mysteries, and in his promotion and regulation of ecclesial worship in the particular Church entrusted to him. In this way he will fulfill the “duty of offering to the divine majesty the worship of the Christian religion and of administering it in accordance with the Lord’s commandments and the Church’s laws,”[40] so that the sacred liturgy may truly be the source and summit of the Christian life. This is a high calling: let us pray for our bishops.

[1] For convenience sake, the terms “particular Church” or “diocese” will be used interchangeably, but they are meant to include all those jurisdictions that are equivalent in law (i.e., territorial prelature, territorial abbacy, vicariate apostolic, prefecture apostolic, permanently erected apostolic administration; see CIC, canon 368), and everything said of a Latin-rite diocese applies congrua congruis referendo to eparchies and exarchies in the Eastern Churches.

[2] St. Augustine, Sermo 340, 1 (PL 38:1483).

[3] Lk 22:32.

[4] John Paul II, Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation Pastores gregis on the Bishop, Servant of the Gospel of Jesus Christ for the Hope of the World, 16.

[5] Canon 904; when the Code uses the word sacerdos, it is meant to include both bishops and presbyters.

[6] Pastores gregis, ibid.

[7] Roman Pontifical, “Ordination of a Bishop,” 40, 70.

[8] Pastores gregis, 39.

[9] Ibid., 13.

[10] Second Vatican Ecumenical Council, Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Lumen gentium, 18-27; Decree on the Pastoral Office of Bishops in the Church Christus Dominus.

[11] Lumen gentium, 21.

[12] Ibid., 26.

[13] John Paul II, Encyclical Letter Ecclesia de Eucharistia on the Eucharist in its Relationship to the Church, 1.

[14] Lumen gentium, 11; cf. Second Vatican Ecumenical Council, Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy Sacrosanctum Concilium, 10.

[15] Sacrosanctum Concilium¸ 41; this form of Mass, which should be sung, is called the “Stational Mass of the Diocesan Bishop” in the Ceremonial of Bishops, 119, 121.

[16] Canons 388-89; a parish pastor has the same obligation for his parishioners (canon 534).

[17] Lumen gentium, 25, citing Council of Trent, session V, Decree on Reform, c. 2, n. 9; and session XXlV, can. 4.

[18] Congregation for Bishops, Directory for the Pastoral Ministry of Bishops Apostolorum Successores, 122 a).

[19] Pastores gregis, 31.

[20] See Lumen gentium, 26.

[21] Ceremonial of Bishops, 404.

[22] Ibid., 406

[23] Canon 863.

[24] Canon 884.

[25] Lumen gentium, 11.

[26] Pastores gregis, 39.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Apostolorum Successores, 144.

[29] Canons 1012, 1015.

[30] Christus Dominus, 15; cf. canon 835, §1, and Apostolorum Successores, 145.

[31] Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, Instruction Redemptionis Sacramentum on Certain Matters to Be Observed or to Be Avoided Regarding the Most Holy Eucharist, 22.

[32] Apostolorum Successores, ibid.

[33] Sacrosanctum Concilium, 22, §3; cf. canon 846, §1.

[34] Canon 834, §2.

[35] Since the bishop must safeguard the unity of the Church, he should promote her common discipline by exercising “vigilance so that abuses do not creep into ecclesiastical discipline, especially regarding the ministry of the word, the celebration of the sacraments and sacramentals, the worship of God and the veneration of the saints” (canon 392).

[36] Canon 838, §4.

[37] Apostolorum Successores, 145-53.

[38] Redemptionis Sacramentum, 21.

[39] United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, “Redemptionis Sacramentum and the Authority of the Diocesan Bishop,” http://www.usccb.org/prayer-and-worship/the-mass/frequently-asked-questions/ redemptionis-sacramentum-authority-diocesan-bishop.cfm, accessed September 10, 2018.

[40] Lumen gentium, 26.