Liturgical Sign Language: Praying with Hands Extended and Hands Joined

Everything about the celebration of the sacred liturgy has meaning and value for our worship of Almighty God. The fullness of this worship takes place with the offering of Jesus in the Eucharist. Our entrance into this Mystery includes not just a spiritual and mental participation but also includes our gestures and bodily postures. In fact, the General Instruction of the Roman Missal (GIRM) insists that gestures and postures of priests and congregation alike “must be conducive to making the entire celebration resplendent with beauty and noble simplicity, to making clear the true and full meaning of its different parts, and to fostering the participation of all” (42).

The liturgical assembly is particularly informed by the various hand positions of the priest celebrant during Mass. These gestures are not arbitrary. Rather, they are rooted in the long tradition of the Church’s rubrics for the celebration of the Eucharist and instinctively connect with the action of the Church’s prayer to foster a deeper participation of all. If gestures are to make clear the true and full meaning of the rites and contribute to the beauty and simplicity of the celebration, then they deserve renewed attention. The current GIRM and Order of Mass (OM) of the Roman Missal give adequate directions for the various hand gestures of the priest celebrant. In all cases, especially in favor of the ars celebrandi, these gestures should be natural, serious, and carried out with intention.

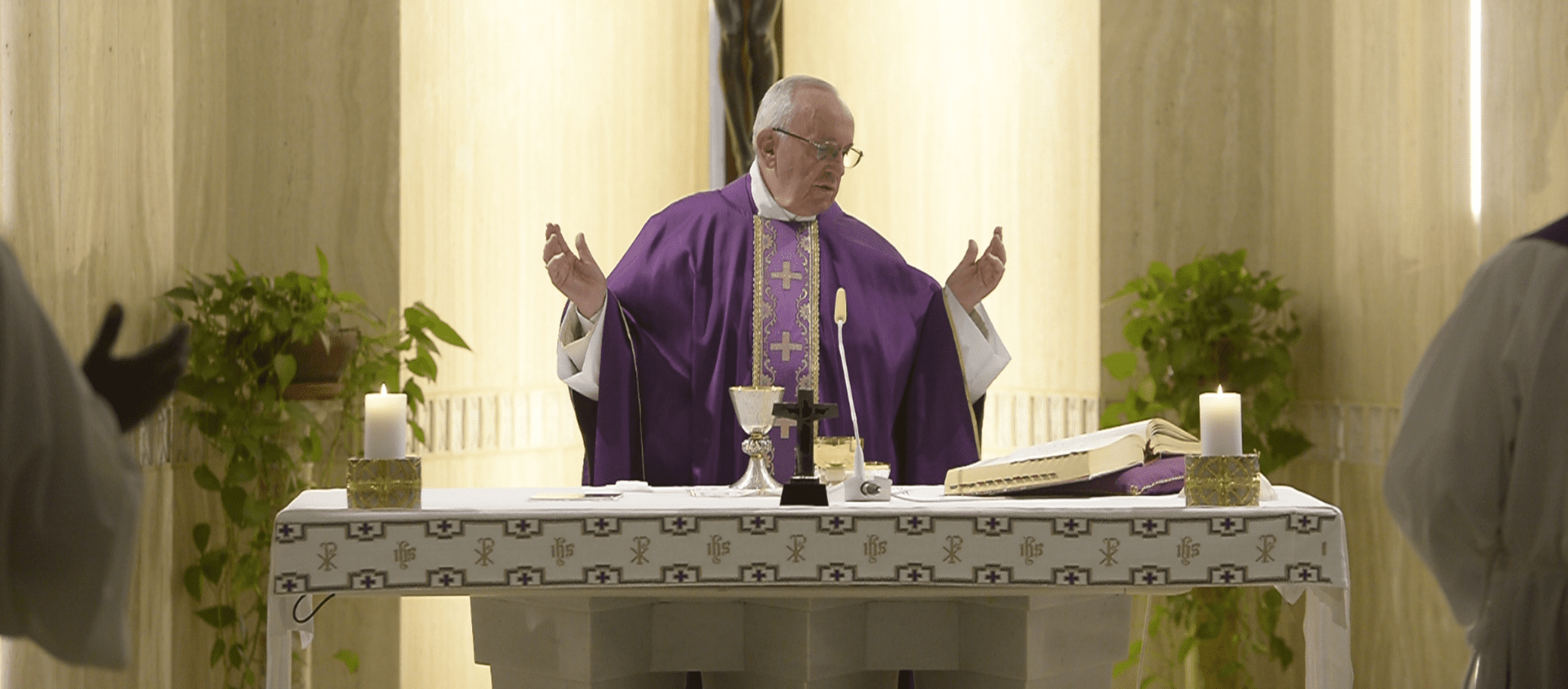

The most frequently employed gesture of the priest celebrant is the orans, the praying position of the hands. Ancient Christian iconography typically displays praying Christians with raised outstretched hands. This rather obvious praying gesture comes to Christianity from Jewish use. The Christians additionally saw in this same gesture an image of Christ offering himself on the cross, the ultimate prayer. The use of the orans therefore identifies the priest celebrant with the Christ and the raising of his own Sacrifice to the Father.

In the celebration of the Eucharist, the priest assumes this orans gesture when he prays in his own name and also on behalf of the Church. The Roman Missal is clear when the orans is to be used. For example, as the priest prays the Eucharistic Prayer, he does so with hands extended—raised outstretched hands. This gesture expresses and corresponds to the liturgical action of the prayer offered with Christ and all to the Father. The naturalness and carefulness of this gesture insures that it is not a distraction but rather leads everyone into the Sacrifice of the Lord.

After the orans, the next most frequent gesture for the priest celebrant is praying with his hands joined, one hand flat against the other in an upward direction. In the tradition, this gesture as well became associated with prayer. In some instances, the Order of Mass is specific when the priest celebrant joins his hands, for example, for the Sanctus. There are other instances when this gesture would be sensible but not specified, for example for the Gloria and the Creed.

For the Collect, the priest celebrant makes use of both the joined hands and the orans. He is directed to keep his hands joined for the “Let us pray” and then extend them for the prayer itself (see GIRM, 127 and OM, 9). The hands here translate the spoken text. The gesture of the joined hands invites the assembly to do what was announced, to pray. The orans for the oration directs those assembled to join in the offering of the prayer to the Father in and with Christ.

These two hand gestures, the orans and joined hands, complement one another throughout the course of the celebration of Mass as they foster and encourage a primary posture of the worship of God for priest celebrant and the faithful. In our next “Ars Celebrandi” entry other gestures of the priest’s hands, such as blessing, striking the breast, and greeting, will be described.

The first part in this series is available by clicking here. The second part is available here.