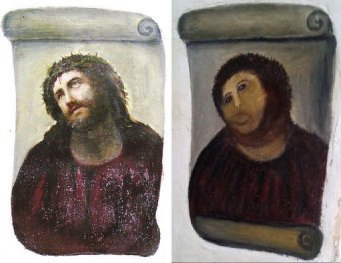

Spanish artist Elias Garcia Martinez was vacationing in Borja, Spain, when he painted the Ecce Homo on the wall of the Borja church in 1930 to express his devotion to God and his thanksgiving to the town that received him on holiday. Crowned with thorns and dressed in purple, Martinez’s image depicts Christ in his agony following his scourging. Over the years since it had been painted, the image deteriorated, its paint flaking away and colors fading.

In a good-will effort to restore the image, a local amateur artist took it upon herself to reverse the damage done by time and the environment’s weather. But without Martinez’s skill to rely on (he had died in 1934), she unintentionally disfigured the painting of the already disfigured man. Once called “Ecce Homo,” critics and internet humorists, playing on the Spanish word for monkey, “mono,” renamed it “Ecce Mono.”

Both liturgical ministers and participants would do well to heed the lessons of the Ecce Homo saga, for “liturgy as art” is the Church’s preferred way of seeing liturgy and liturgical practice today.

Consider Cardinal Ratzinger’s comparison of the liturgy in 1918 and 2001, in the Introduction to his book, The Spirit of the Liturgy:

“We might say that in 1918, the year that Guardini published his book [The Spirit of the Liturgy], the liturgy was rather like a fresco. It had been preserved from damage, but it had been almost completely overlaid with whitewash by later generations. In the Missal from which the priest celebrated, the form of the liturgy that had grown from its earliest beginnings was still present, but, as far as the faithful were concerned, it was largely concealed beneath instructions for and forms of private prayer. The fresco was laid bare by the Liturgical Movement and, in a definitive way, by the Second Vatican Council. For a moment its colors and figures fascinated us. But since then the fresco has been endangered by climatic conditions as well as by various restorations and reconstructions. In fact, it is threatened with destruction, if the necessary steps are not taken to stop these damaging influences. Of course, there must be no question of its being covered with whitewash again, but what is imperative is a new reverence in the way we treat it, a new understanding of its message and its reality, so that rediscovery does not become the first stage of irreparable loss” (The Spirit of the Liturgy, 8-9).

The “fresco” of the liturgy, having suffered climatic damage, needs caution and care in its restoration, lest our beholding of The Man become impossible. What does this mean for us amateur artists who depict the Lord’s liturgical face not as professionals but as lovers (the meaning of “amateur”)?

First, we should be able to see the liturgy’s celebration through the hermeneutic of ars celebrandi, the “art of celebrating.” The ars celebrandi, writes Pope Benedict, “is the fruit of faithful adherence to the liturgical norms in all their richness” (Sacramentum Caritatis, 38). In this regard, the rubrics, rules, and norms are not simply to be followed for their own sake (although obedience to a Mother’s rule is not without merit); rather, these elements are the means by which the liturgy’s unseen reality—Jesus—shows himself. “Art is limitation,” G.K. Chesterton says, and the artist must follow the rules of nature. “If you draw a giraffe, you must draw him with a long neck. If in your bold creative way you hold yourself free to draw a giraffe with a short neck, you will really find that you are not free to draw a giraffe.” A supernatural artist, such as the liturgy’s ministers, must similarly follow the liturgical laws, which allow us to ecce homo as he is, without distortion or disfigurement.

Thankfully—and this is the second point to bear in mind—the Holy Spirit is the principal artist of the ars celebrandi. “In the liturgy,” says the Catechism, “the Holy Spirit is teacher of the faith of the People of God and artisan of ‘God’s masterpieces,’ the sacraments of the New Covenant” (1091). The radiant beauty of the liturgy is not, consequently, left entirely, or even mostly, to the skill of the minister. Intelligently faithful to the liturgy’s rubrics and animated by the Spirit, the celebrant creates a treasure to behold. The rubrics, or “red print” in the liturgical books, stem from the Latin ruber, or “red,” the same source which gives us the word “ruby.” The Second Vatican Council says that the pastor is to be aware that during the liturgy “something more is required than the mere observation of the laws governing valid and licit celebration” (Sacrosanctum Concilium, 11). This “something more” is an awareness that the subject of the priest’s art is Jesus and his saving work. The minister, the Church’s rubrics, and the Holy Spirit’s inspiration together create an Ecce Homo of immense beauty to encounter.

A third consequence of liturgy as ars celebrandi falls to the faithful in the assembly. Celebrating the liturgy as the work of art that it is, the faithful’s participation can be elevated to a deeper level. Pope Benedict, in his key treatment of ars celebrandi in the 2007 exhortation Sacramentum Caritatis, says the “primary way to foster the participation of the People of God in the sacred rite is the proper celebration of the rite itself. The ars celebrandi is the best way to ensure their actuosa participation [active participation]” (38). When the liturgical fresco is not covered in whitewash or deteriorating from climatic conditions—when the Ecce Homo shows its essential radiance—participants can encounter the saving mystery. But this also requires formation in a type of supernatural “art appreciation.” In his famous 1964 letter to the Mainz liturgical conference, Romano Guardini emphasized liturgical participation through a kind of contemplative looking:

“The liturgical act can be realized by looking. This does not merely mean that the sense of vision takes note of what is going on in front, but it is in itself a living participation in the act…. Only if regarded in this way can the liturgical-symbolical action be properly understood; for instance the washing of hands by the celebrant, but also liturgical gestures like the stretching out of hands over the chalice. It should not be necessary to have to add in words of thought, ‘that means such and such,’ but the symbol should be ‘done’ by the celebrant as a religious act and the faithful should ‘read’ it by an analogous act; they should see the inner sense in the outward sign. Without this everything would be a waste of time and energy and it would be better simply to ‘say’ what was meant. But the ‘symbol’ is in itself something corporal-spiritual, an expression of the inward through the outward, and must as such be co-performed through the act of looking.”

The liturgy is our weekly occasion of Ecce Homo! It is a beautiful work of sacred art. Its subject is The Man, Jesus. The Holy Spirit is the work’s principal artist, and he leads priests and ministers to complete the masterpiece. Our Mother the Church guides our humble hands, directing them to portray accurately her Bridegroom. The faithful, with eyes prepared to see and ears ready to hear, bask in the radiant beauty of The Man and, indeed, add their own brush strokes, each guided by a love and knowledge of the liturgy, to complete the image.

As the saying goes, “I don’t know much about art, but I know what I like.” And I would love to like a liturgy that looks more like what Martinez’s work intended and not what it had become.