Pope St. John Paul II designated the octave day of Easter as Divine Mercy Sunday, which has flowered into exuberant celebrations throughout the globe. But how does the Second Sunday of Easter stand in relation to the first day of Easter? The octave day of the Lord’s Resurrection opens a pathway for the Church to appropriate more deeply and take into herself the Mystery of the Lord’s victory over death.

Christians know that love is the meaning of life, that love is the origin from which man buds forth and the end toward which the universe and each person in it is tending. But this truth is hardly self-evident. Indeed, the universe seems to teach otherwise: galaxies grow further apart; emptiness fills the universe; our Sun will stop shining; the earth is growing old; resources dwindle; people go hungry; addiction runs rampant; murder; rape; slavery; abortion; hatred; violence. Every one of us is dying.

Yet, like St. Paul, those who encounter the Resurrected One, Jesus Christ, can say:

When the perishable puts on the imperishable,

and the mortal puts on immortality,

then shall come to pass the saying that is written:

“Death is swallowed up in victory.

O death, where is your victory?

O death, where is your sting?”(1 Corinthians 15:54–55)

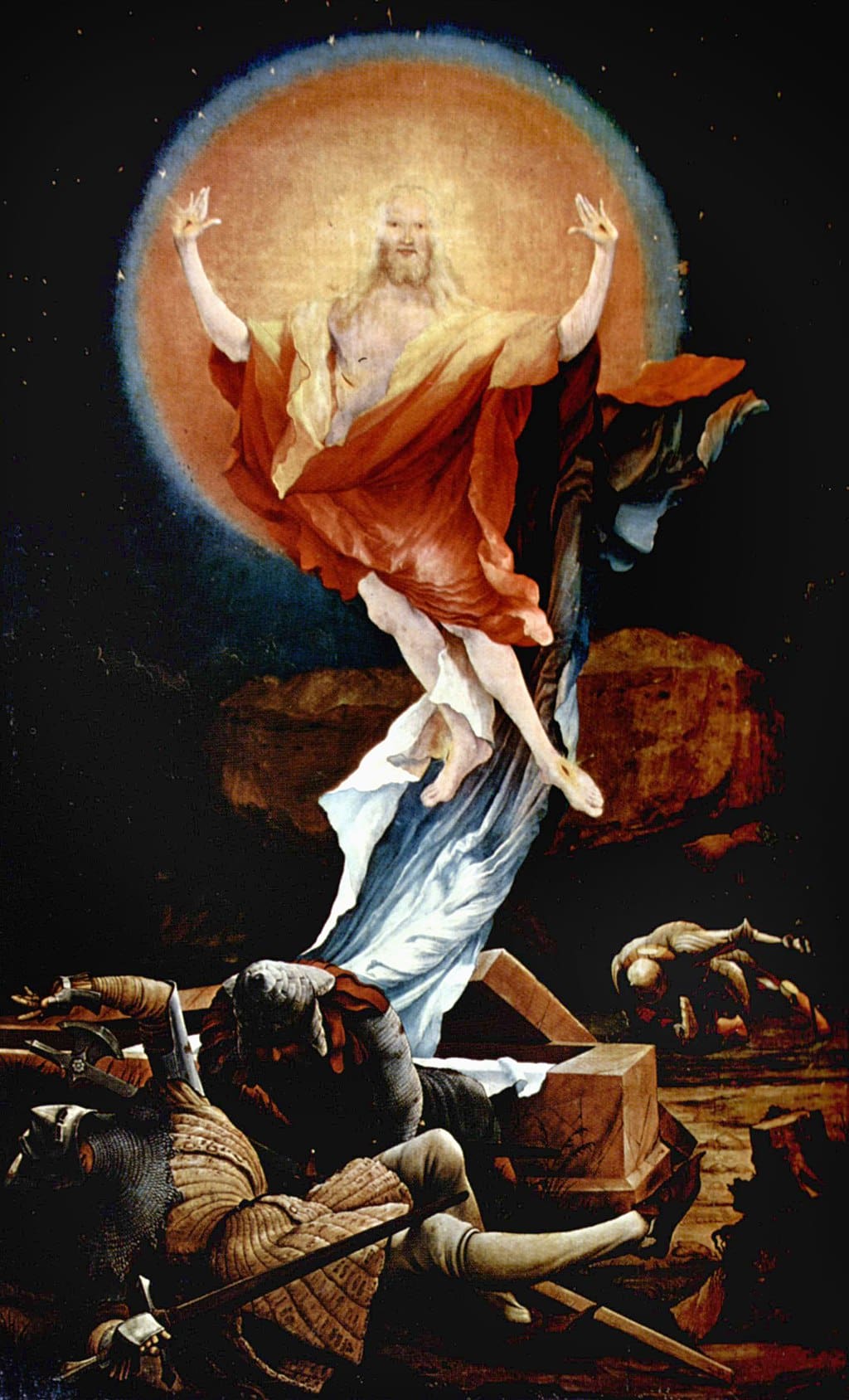

The Cross and Resurrection of Jesus Christ make clear that sin and death are not the ultimate meaning of life. It is this death-shattering event that makes “this holy building shake with joy”[1] at the Easter Vigil. The Easter Sequence, which can be sung throughout the Easter Octave,[2] celebrates this great victory:

Christians, to the Paschal Victim

Offer your thankful praises!

A Lamb the sheep redeems;

Christ, who only is sinless,

Reconciles sinners to the Father.

Death and life have contended [duello] in that combat stupendous [conflixere mirando]:

The Prince of life, who died, reigns immortal.

Speak, Mary, declaring

What you saw, wayfaring.

“The tomb of Christ, who is living,

The glory of Jesus’ resurrection;

Bright angels attesting,

The shroud and napkin resting.

Yes, Christ my hope is arisen;

To Galilee he goes before you.”

Christ indeed from death is risen, our new life obtaining.

Have mercy, victor King, ever reigning![3]

That this Sequence to the Paschal Victim is sung throughout the Octave of Easter clues us into the reality of the eighth day. Of the eighth day, David Fagerberg remarks:

The Resurrection of Christ, which completed the Paschal Mystery and our salvation, was like a day unseen since the book of Genesis. This day after the seventh day—the eighth day—is a work of eternity in the midst of time. Although it doesn’t change the calendar count for the remaining weeks in the month, nonetheless eternity has wiggled into history and set a pace for God’s kingdom. Christians gather every eighth day to celebrate the Paschal mystery of redemption.[4]

For St. John, this day of Jesus’ Resurrection is not initially the eighth day, but rather the “first day of the week.” It is the “first day” because it is the day that a new covenant is sealed with a new creation. In The Spirit of the Liturgy, Joseph Ratzinger comments:

The eighth day, therefore, signifies the new time that has dawned with the Resurrection. It is now, so to speak, concurrent with history. In the liturgy we already reach out to lay hold of it. But at the same time it is ahead of us. It is the sign of God’s definitive world, in which shadow and image are superseded in the final mutual indwelling of God and his creatures. It was to reflect this symbolism of the eighth day that people liked to build baptisteries, baptismal churches, with eight sides. This was meant to show that Baptism is birth into the eighth day, into the Resurrection of Christ and into the new time that opened up with the Resurrection.[5]

In terms of its liturgical quality, the celebration of an octave opens up the inner essence of what was accomplished in salvation history to its reception by the faithful so that they may “lay hold of” that which is “ahead of us” in time. As Orthodox theologian Vigen Guroian writes, the

theology of the eighth day, or octave, is then rooted in the Easter event. Every Sunday, henceforth, belongs to and also breaks from the weekly cycle of ordinary time into a new aeon, a New Creation, so that Christians live from Sunday to Sunday. Each week the church lives “into” the New Creation through the liturgy. There is a profound difference between the modern habit of living from weekend to weekend and the Christian rhythm of the week. The recreation of the first and eighth day is radically different from the recreation of a secular weekend. The Apostolic Constitutions specifically prescribe that the eighth day after certain major feasts be called the octave. Strictly speaking, the octave repeats the feast’s celebration, and normally this falls on the Sunday following the feast. The octave is not just a repetition of the feast, however. It deepens important dimensions of that feast, or makes more explicit that feast’s connection with other important Christian beliefs and practices. Epiphany, Easter, and Pentecost are exemplary of the octave in early Christian worship.[6]

In Jesus’ Resurrection on Easter day, the new creation that was supposed to come at the end of time has already come to meet us here and now. So the octave day of Easter is a repetition of the feast, but deepens certain dimensions of the Resurrection for those participating in it.

John’s Gospel illustrates this new creation emphasis of Jesus’ Resurrection in many ways, some of which are Jesus’ Resurrection itself, John’s emphasis on the “first day” as an allusion to the first creation, his portrayal of Jesus as the “gardener” (20:15) as an allusion to God planting a garden in Eden during the first creation (see Genesis 2:8), and Jesus’ breathing[7] on the Apostles (20:22) as an allusion to God breathing the breath of life into Adam in the first creation (Genesis 2:7). Admittedly, John’s “eight days later” phrase could simply be a further emphasis on the next occurrence of the “first day;” however, in accord with the Jewish usage of the eighth day as a culmination point,[8] John’s portrayal of Jesus’ meetings with the Apostles over these two Sundays bears the character of a fulfillment.

Craig S. Keener’s incisive comment is helpful in seeing the eighth day as tending toward fulfillment or completion: “The parallel between the two appearances [of Jesus to the Apostles (John 20:19–23 and 26–29)] suggests that something remains incomplete until Thomas’s confession of Jesus with its high Christology”: My Lord and my God! (John 20:28).[9] In the post-Resurrection narrative, John uses the time indicators “first day” and “eight days later” as a means of illustrating that the new creation begun with Jesus’ Resurrection remains to be appropriated by the act of believing (Thomas being an example): “that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name” (20:31). Jesus’ life and ministry reveals the new creation breaking into the world, and the Resurrection inaugurates the new creation in a way that goes to the very root of the sin and death that caused creation to come undone. Jesus himself gives us a sense of what new creation looks like: “the blind receive their sight and the lame walk, lepers are cleansed and the deaf hear, and the dead are raised up, and the poor have good news preached to them” (Matthew 11:5). So, while Jesus brings the new creation with him, from the first day to the eighth day there is described a tension between the now and the not yet, a realized eschatology that nevertheless awaits its consummation in all who receive him and believe in his name (cf. John 1:12).

It is the relieving of this tension, (i.e., knowing the Lord Jesus and his mercy toward me) in which we are called to participate on the eighth day of the Easter octave, which Pope St. John Paul II named Divine Mercy Sunday: “Put your finger here and see my hands, and bring your hand and put it into my side, and do not be unbelieving, but believe” (John 20:27 NABRE). Indeed, it is because the octave day calls us to appropriate the meaning of the Lord’s Mercy more deeply in our lives that the Mystery of the Resurrection is revealed as the fruit of a combat that Jesus won for “us men and for our salvation.”[10] Singing the Easter Sequence throughout the Octave of Easter (including Divine Mercy Sunday)[11] prepares our hearts for a full reception of the Lord’s victory over death on Divine Mercy Sunday. The Octave of Easter is a call for all of us to have that encounter with the Risen One that opens up our hearts anew to discover the “new life” he has obtained for us. As Pope Benedict XVI writes, with the eighth day the

structure of the week is overturned. No longer does it point towards the seventh day, as the time to participate in God’s rest. It sets out from the first day as the day of encounter with the Risen Lord. This encounter happens afresh at every celebration of the Eucharist, when the Lord enters anew into the midst of his disciples and gives himself to them, allows himself, so to speak, to be touched by them, sits down at table with them.[12]

May we encounter the Lord’s Divine Mercy anew this renewed Easter Day.

[1] The Roman Missal: Renewed by Decree of the Most Holy Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, Promulgated by Authority of Pope Paul VI and Revised at the Direction of Pope John Paul II, Third Typical Edition. (Washington D.C.: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), 353.

[2] United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Lectionary for Mass: For Use in the Dioceses of the United States of America, Second Typical Edition. (United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 1998–2002), Appendix I: Sequences.

[3] United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Lectionary for Mass: For Use in the Dioceses of the United States of America, Second Typical Edition (United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 1998–2002), §42, emphasis mine.

[4] David W. Fagerberg, Christian Meaning of Time: Feasts, Seasons, and the History of Salvation, 34.

[5] Joseph Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy (trans. John Saward; San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2000), 97.

[6] Vigen Guroian, The Melody of Faith: Theology in an Orthodox Key (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2010), 21.

[7] “This appears to complete, symbolically, the inclusio between the reference to the first creation at John 1:1–4 by indicating a new creation—the establishment of a new messianic community by the risen Jesus—through Jesus’ ‘breathing on’ his disciples (an unmistakable allusion to Gen 2:7 LXX, where the same word is used).” Andreas J. Köstenberger, A Theology of John’s Gospel and Letters: The Word, the Christ, the Son of God (Biblical Theology of the New Testament; Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2009), 259. Emphasis, original.

[8] Frank-Lothar Hossfeld and Erich Zenger, Psalms 3: A Commentary on Psalms 101–150 (ed. Klaus Baltzer; trans. Linda M. Maloney; Hermeneia—A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible; Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2011), 258.

[9] Craig S. Keener, The Gospel of John: A Commentary (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2012), 1210.

[10] The Roman Missal: Renewed by Decree of the Most Holy Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, Promulgated by Authority of Pope Paul VI and Revised at the Direction of Pope John Paul II, Third Typical Edition. (Washington D.C.: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), 527.

[11] Since “the first eight days of Easter Time constitute the Octave of Easter and are celebrated as Solemnities of the Lord” and the Easter Sequence can be sung “throughout the Easter Octave” (see above), the Easter Sequence can be sung on Divine Mercy Sunday. The Roman Missal: Renewed by Decree of the Most Holy Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, Promulgated by Authority of Pope Paul VI and Revised at the Direction of Pope John Paul II, Third Typical Edition. (Washington D.C.: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), 113: Calendar Norms, §24.

[12] Benedict XVI, Homilies of His Holiness Benedict XVI (English) (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2013), Easter Vigil, 23 April 2011.