New Book Shows Liturgical Design Behind Rise and Fall—and Resurrection—of God’s Temple

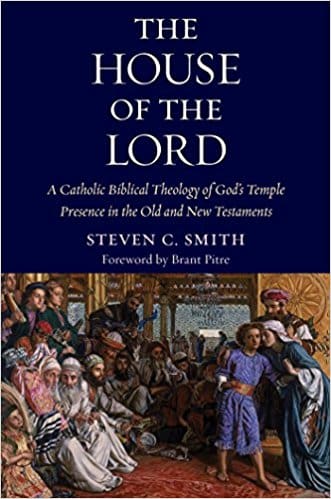

The House of the Lord: A Catholic Biblical Theology of God’s Temple Presence in the Old and New Testaments by Steven C. Smith, Steubenville, OH: Franciscan University Press, 2017. 392 pp. ISBN: 978-0996930543. $60 (hardcover).

The House of the Lord: A Catholic Biblical Theology of God’s Temple Presence in the Old and New Testaments by Steven C. Smith, Steubenville, OH: Franciscan University Press, 2017. 392 pp. ISBN: 978-0996930543. $60 (hardcover).

“But who do you say that I am?” Our Lord addresses this query to the first twelve bishops of the Church, his Apostles, but the question is meant for all of us. It is one of the fundamental question of life. Who is Christ and who do we say he is?

In liturgical circles over the past 60 years, though, another related and fundamental question has been, “What say you of the Temple?” Is the Temple and its sacrifices the primary source of our liturgical roots, or is it the Synagogue and its scriptures? Or perhaps the family home? Seeing “the Temple and the sacrificial priesthood in its proper place at center stage” of the scriptures allows the relationship between Jesus and the Temple to become “more coherent” (4). Seeing that St. Luke’s Gospel begins in the Temple with the annunciation to Zechariah and ends with the apostolic band “continually in the Temple blessing God” (Lk 24:53), we are able to more clearly understand why the Temple is so important in the Gospels—and for the liturgy. For instance, we better understand incidents like Jesus’ cleansing of the Temple (Lk. 19:45-48) in relation to the priestly-sacrifice which occurred there. If Jesus was challenging the daily whole-offering (tamid) as a means of atonement, it was because he was preparing us, three chapters further along in Luke, for the institution of the Eucharist (Lk. 22:14-20), which clearly takes “the place of the daily whole-offering…table for table, whole offering for whole offering.”[1] To help us better understand these connections, Steven C. Smith’s The House of the Lord: A Catholic Biblical Theology of God’s Temple Presence in the Old and New Testaments offers a comprehensive view of the Temple and its relationship to the drama of salvation history.

Houses of the Holy

The course of events which Smith examines in The House of the Lord amount to a series of flawed attempts in scripture to build a temple that will be pleasing to the Lord. Smith begins with the Temple of Eden where Adam stands as priest-king of the Garden, charged with kingly and priestly tasks—to “fill the earth and subdue it” (Gen 1:28), as well as to “till” and “keep” (Gen 2:15) the garden sanctuary—technical terms for cultic activity. Smith sees this as man’s overall mission—ultimately fulfilled by the “root of Jesse” (Is. 11:10)—to expand the original Edenic Temple, to “fill the earth” with the “knowledge of the glory of the Lord” (Hab 2:14; cf. Is 11:9). Not only does Adam fail, however, but man is later confounded in the building of the “Tower of Babel”—a temple, Smith notes, which man has dedicated not to God but to himself. Later in the Old Testament, Smith examines how even the Patriarchs regularly build altars, approximating the temple-building task originally given to Adam in the garden.

Significantly, Smith notes that Moses is finally able to establish a Temple with the construction of the desert Tabernacle. But Moses only succeeds because his building plans are based on the pattern of God’s Temple—a structure that was not made with human hands. Rather than creating the design himself, Moses finds his design after witnessing it on Mt. Sinai in the desert Tabernacle.

From Moses, Smith moves on to the ultimately successful effort to build a Temple during the time of Israel’s kings. With David, the Temple becomes “the embodiment” of God’s kingdom-covenant with his people, where “the triple relationship” between the Lord, the “House of David and the people of Israel was established” (151). As the Kingdom of Israel reaches its flowering in the actual Temple built by David’s son, King Solomon, an internalization and universalization takes place, embodied in Isaiah’s prophecy that in the “latter days” the “law and the word of the Lord” will cause all “the nations [to] stream toward” the “mountain of the house of the Lord” (Is 2:2–3; cf. Smith, 178–9). In the end, though, Smith notes, even this First Temple does not last and, after Israel’s return from exile, must be replaced by a second Temple. The destruction and rebuilding of the Temple, combined with the corruption of the high priesthood and foreign occupation, made Israel ripe for counter-temple movements, the likes of which were ubiquitous in first-century Palestine.

Dwelling on a New House

The hopes for a “new David” were also tied to the construction of the new Temple (151): the “embodiment” of God’s kingdom-covenant with David (151). This new David, just like David himself, would reunite all Israel; defeat Israel’s enemies; build and restore the Temple; establish the forgiveness of sins; and draw the nations to the Lord (239–240). Each of these five “hopes associated with the coming Messiah can be traced back, in one way or another, to the Davidic covenant and to the establishment of the House of the Lord, the Temple” (239).

One hope, the forgiveness of sins, emerges with John the Baptist. With his offer to forgive sins once reserved for the Temple precinct, we see that a restored Temple is “already taking shape” as Jesus is coming on the scene (251). Jesus’ miracles and exorcisms “represent an unprecedented outpouring of forgiveness and mercy, formerly associated with God’s presence in the Temple” (266). Indeed, the Temple “was the primary venue for healing within Judaism” (268). As such, Jesus’ notoriety can be understood in light of all his miracles and exorcisms: he was understood to be “the mobile embodiment of the Temple” (268). Just like the high priest’s garments, whoever touches Jesus becomes holy (268).

Christ’s Church is another hope fulfilled. As the “Davidic Messiah, who, like the son of David,” builds a Temple, Peter is given a “priestly authority” not simply over the Kingdom of Heaven, but over the ekklesia/Temple that will be built upon Peter (265). Indeed, “something greater than the Temple” and “greater than Solomon,” the original Temple builder, is here (Mt 12:6, 46). As witnessed by the apostles in their work after Christ’s ascension and the coming of the Holy Spirit, Jesus’ proclamation of the Kingdom of God represents a temple-building mission, whereby he was “filling the earth” with God’s glory by filling and uniting men in the Holy Spirit (258; see 330–332). Jesus’ death and resurrection (cf. Jn 2:19) constitute the new Temple of the Spirit in his flesh (see Heb 10:20; 356). It might be said that “The Word became the eternal High Priest and perfect offering—in every way He is the Temple of God” (358).

Liturgical Blueprint

The significance of The House of the Lord for the study of the Liturgy is that it puts “God’s Temple presence” under the wide-angle lens of biblical theology—situating the Temple and its “significance within the larger framework of the biblical canon” (3). While there are many merits to historical criticism, the post-Vatican II period saw less and less of the insightful works produced by Jean Daniélou and Yves Congar (especially Congar’s The Mystery of the Temple). In contrast, Smith offers a “typological-sacramental” reading of the Scriptures which is “not merely salvation-historical, but also sacramental and liturgical” (Foreword by Brant Pitre, xii). Such an approach helps us to understand why biblical scholars such as E.P. Sanders can assert that it is “almost impossible to make too much of the Temple in first-century Jewish Palestine” (xi). Yet, much of Protestant and indeed Catholic scholarship over the last 150 years has applied the views of Lutheran biblical scholar Julius Wellhausan’s anti-priestly ideology to see the Temple and its priesthood as “devolution[s] away from the purer moral law of Deuteronomy” and the prophets (6). Thus, Smith notes, “the characterization of Jesus as a priestly Messiah or of the priestly identity of Jesus’ Apostles are all but absent in many studies of the Gospels today” (7). The Temple theme runs, as Smith puts it, like fiber optic cable from Genesis to Revelation, as God builds the temple-sanctuary of the first creation and the temple-city of the new creation.

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of The House of the Lord is the upshot that Jesus’ temple-building mission has for our understanding of the liturgy—and indeed of the liturgical foundations for the church building itself. Smith spends the conclusion of the book exploring the “impact and reception of the temple theme within the early Church” (375). Since the mission of Jesus is to restore the proper communion between God and man begun in Eden, embodied in the Temple, accomplished in the Resurrection and Pentecost, prefigured in the mysteries of the Ascension, and envisioned in the final chapters of Revelation, the liturgy and the church building are meant to embody the union and communion between God and man.

Model Home

As an example of this awareness in the early Church, Eusebius of Caesarea relates the centrality of Christ and the Temple in relation to the building of a church at Tyre: “But the Father having proved Him now as well as then,” he writes, “has established him as the head of the corner of this our common church. This, therefore, the living temple of the living God, formed of yourselves, I say, is the greatest and the truly divine sanctuary, whose inmost shrines, though invisible to the multitude, are really holy, a holy of holies.”[2]

Indeed, as Eusebius suggests, the church building is the very trysting place between God and man where, in Christ and his Church, heaven and earth overlap and interlock. While the “aims of [Smith’s] conclusion are modest” (375), gaining a nuanced biblical theology of the Temple and its priesthood opens the way for nuanced Christological application in countless ways and reminds us that “all aspects of worship: architecture, sacred music, and even…iconography” are at the service of the Lord (376, quoting Bouyer).

Perhaps the great payoff of Smith’s book, which solidly presents a biblical theology of the Temple, is the way it broadens the horizons of liturgical theology. Too often the time given to the Bible hardly allows “for a theme to be developed from the perspective of Scripture itself or questions from the Bible to be raised that were not covered in the body of the Church’s teaching.”[3] This focus on the Temple as prefigurement of Christ avoids what Anglican biblical scholar N.T. Wright has described as a methodological problem with approaching sacramental theology from isolated dogmatic texts: by starting with “what you believe about Baptism or Eucharist,” you “will simply collapse into the rather sterile antithesis between different, well-known, well-marked theological positions.”[4] By locating God’s Temple Presence on a larger biblical map, Smith opens new horizons, thereby enabling new conversations in liturgical theology. While Smith’s grounding of the Sacraments in Scripture’s covenantal narrative does not solve debates, The House of the Lord: A Catholic Biblical Theology of God’s Temple Presence in the Old and New Testaments creates new points of entry—new doors and windows for new light to enter and illuminate our understanding of the importance that the historical Temple of the Old Testament holds, especially in its relationship to the Living Temple, Jesus Christ.

[1] Jacob Neusner, “Money-Changers in the Temple: The Mishnah’s Explanation,” New Testament Studies 35 (1989): 287–290, at 289–90.

[2] Eusebius, An Ecclesiastical History to the 20th Year of the Reign of Constantine, trans. Parker S.E. (London: Samuel Bagster and Sons, 1847), 416 [10.4].

[3] Joseph Ratzinger, “Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation: Chapter VI,” in Commentary on the Documents of Vatican II, ed. Herbert Vorgrimler (New York: Herder and Herder, 1967-1969), 3:267.

[4] N.T. Wright, “Space, Time, and Sacraments: Part One” a public address given at Calvin College on January 6th, 2007, accessed February 26, 2018, http://worship.calvin.edu/resources/resource-library/space-time-and-[4]