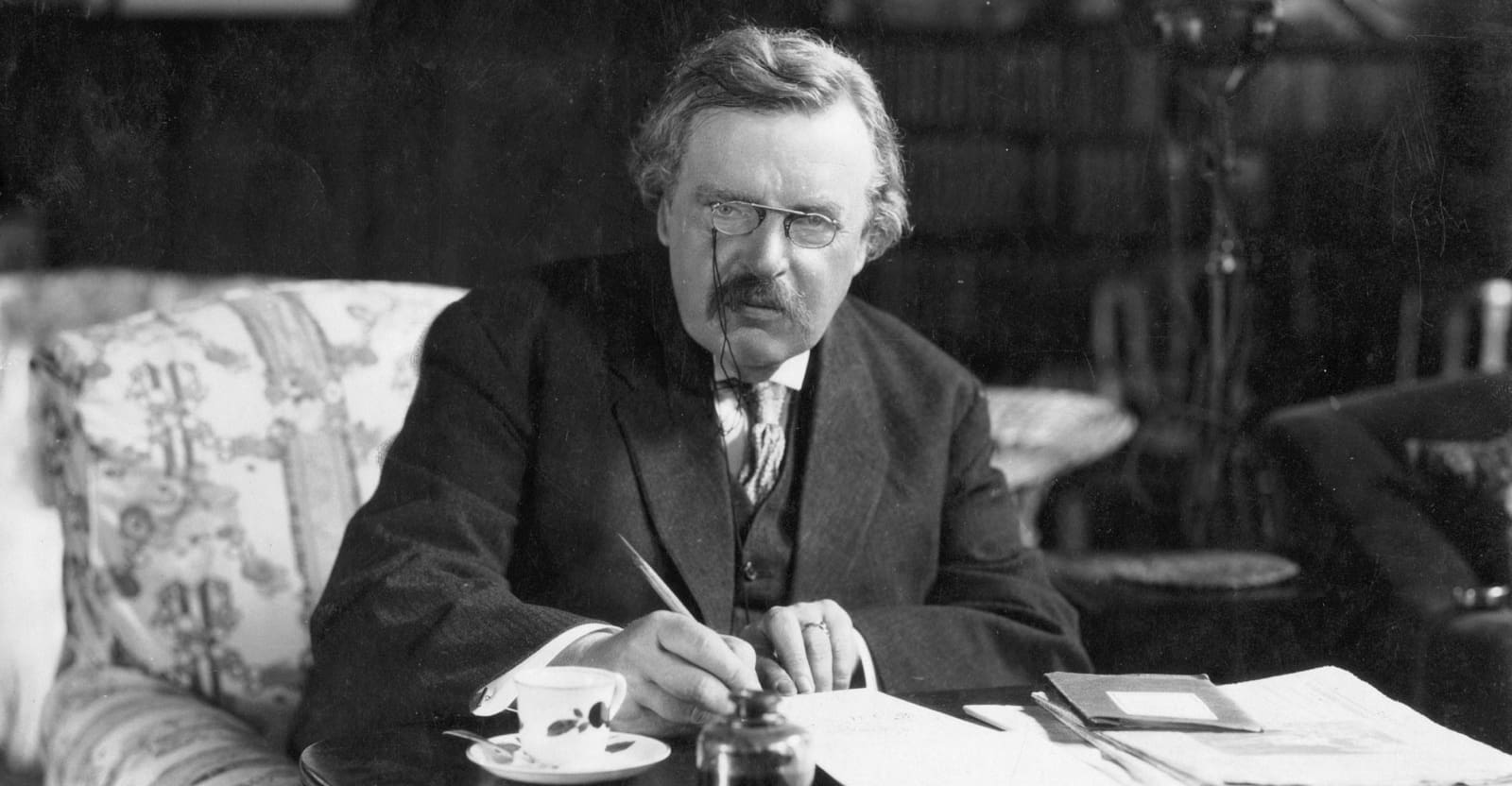

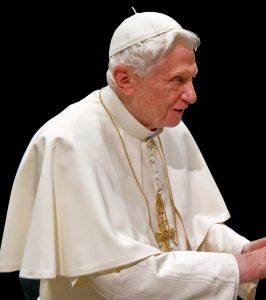

On July 7, 2007, Pope Benedict XVI liberalized the celebration of the Holy Mass according to the Missal of John XXIII with his Apostolic Letter Summorum Pontificum. On the same day, in a separate letter to the bishops of the world (Con grande fiducia), the Holy Father explained the motive behind his decision, stating that “it is a matter of coming to an interior reconciliation in the heart of the Church.”1

If we are going to speak intelligently about the relationship between the Ordinary Form and the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite, I think that this is the key line from which we need to begin our conversation. Pope Benedict is not reintroducing the traditional liturgy as an antiquarian who likes to keep old things on his bookshelf. Nor is he doing this as an archenemy of the liturgical reform, as some have made him out to be. Remember that he was a proponent of the reform during the Council and has never ceased to defend the Council as a whole—including Sacrosanctum Concilium.

Rather, Pope Benedict issued this motu proprio because he saw the sheep wandering off without a pastor. The Holy Father, concerned with the unity of the Church, laments that “Looking back over the past, to the divisions which in the course of the centuries have rent the Body of Christ, one continually has the impression that, at critical moments when divisions were coming about, not enough was done by the Church’s leaders to maintain or regain reconciliation and unity. One has the impression that omissions on the part of the Church have had their share of blame for the fact that these divisions were able to harden.”2

One Divided by Two?

The motu proprio Summorum Pontificum, therefore, is an act of generosity on the part of the vicar of the Good Shepherd aimed at maintaining unity and regaining reconciliation where disunity has arisen. Benedict does not want to be with the lot of those who “have had their share of blame for the fact that these divisions were able to harden.”

Let’s take a look at some of these divisions:

1. Apparent Schism: Since the episcopal consecrations of 1988, there has been a community of baptized Christians, with a valid priesthood, a valid Eucharist, the same Canon of Scripture and the same Creed, who celebrate the Liturgy according to norms that were universal until 50 years ago, who claim that the Holy Father is truly the Vicar of Christ, but are in a dubious state of obedience to him. This is the Fraternity of St. Pius X.

2. Theological disagreement over the nature of the Holy Mass: Cardinal Ratzinger highlighted this in The Feast of Faith: “The crisis in the liturgy (and hence in the Church) in which we find ourselves has very little to do with the change from the old to the new liturgical books. More and more clearly we can see that, behind all the conflicting views, there is a profound disagreement about the very nature of the liturgical celebration, its antecedents, its proper form, and about those who are responsible for it.”3

3. Disenchantment with celebration of the Novus Ordo: Pope Benedict refers to this directly in his letter, writing, “This occurred above all because in many places celebrations were not faithful to the prescriptions of the new Missal, but the latter actually was understood as authorizing or even requiring creativity, which frequently led to deformations of the liturgy which were hard to bear. I am speaking from experience, since I too lived through that period with all its hopes and its confusion. And I have seen how arbitrary deformations of the liturgy caused deep pain to individuals totally rooted in the faith of the Church.”4 Note that this has more to do with the way that the modern Mass is celebrated than a critique of the Missal itself.

4. Psychological vertigo: Nearly every aspect of the Roman Liturgy was changed and restructured in a period of years. The Mass according to the Novus Ordo—as it is experienced by the people—differs radically from the experience of the Mass according to the pre-Conciliar books. The Book of Blessings is incomparable to the blessings found in the Roman Ritual. The prayers are different. The lectionary is different. The music is different. The language is different. The architecture of the parish is different. It would be naïve to think that these dramatic series of changes would not cause at the very least some type of psychological disorientation among the people of God. Blessed Paul VI clearly understood this, as he spoke in a 1969 General Audience on the coming changes, “We must prepare for this many-sided inconvenience. It is the kind of upset caused by every novelty that breaks in on our habits. We shall notice that pious persons are disturbed most, because they have their own respectable way of hearing Mass, and they will feel shaken out of their usual thoughts and obliged to follow those of others. Even priests may feel some annoyance in this respect.”5

In light of such discord and disturbances, Christ’s faithful have done a pretty good job of hanging on. Summorum Pontificum is, in part, an acknowledgement of something that every doctor knows: you can only do so many surgeries at once. Even if they are all good and all aimed at full health—at some point you need to send the patient home to rest for a bit.

Blueprints for a Bridge

What I am intending to convey here is that before we look at the theological, liturgical, canonical, and practical content of the relationship between the Ordinary Form and the Extraordinary Form, we must consider the Holy Father’s intention to act as the “perpetual and visible principle and foundation of unity of both the bishops and of the faithful.”6 He sees a divided Church, a group very much on the peripheries of communion, those who are brokenhearted, confused and some quite angry. What good shepherd would not ask: “Is there nothing we can do?”

Those who work in the ecumenical realm will immediately recognize the application of the words of Unitatis redintegratio: “Whatever is truly Christian is never contrary to what genuinely belongs to the faith; indeed, it can always bring a deeper realization of the mystery of Christ and the Church.”7 If such can be said about what once was ours and has been reshaped outside of the Church, how much more is it true for that which has always been ours and left unmodified?

Summorum Pontificum, therefore, is a tool towards reconciliation and unity. If we are to understand it correctly, we must acknowledge that there has been and continues to exist disunity, and that we cannot discount this disunity as acceptable collateral damage. The people most interested in the Extraordinary Form hold the same faith as those observing the Ordinary Form. Both adore the same God. Both profess the same Creed, and both groups understand it in the same way. Catholics attracted to the Extraordinary Form and those drawn to the Ordinary Form have been baptized with the same baptism. They eat the same Body and drink the same Blood. Both are sons of the same Mother.

As you can tell, I believe that the greater onus in this work of reconciliation and unity falls upon the “Novus Ordo folk.” I think that this position is Scriptural, coming to us from St. Paul: “Now, we that are stronger ought to bear the infirmities of the weak and not to please ourselves” (Rom 15:1). I do not want to imply that the friends of the traditional liturgy are weak in the physical, emotional, or psychological sense. The fortitude that they have shown over the last 50 years shows that to be patently false. However, they are the weak insofar as they are the minority in the Church. It is extremely difficult to find an Extraordinary Form Mass in most dioceses. Where they are offered, generally they are at inopportune hours or only once or twice a month, as though the 3rd Commandment were suspended for them. They have at times been ridiculed, mocked, and publicly shamed by their local priests and bishops. Some have been derided by theologians, liturgists, diocesan curia, directors of religious education, and parish worship councils. When they finally find somewhere friendly to them, within a few years the pastor is moved and the new one either kicks them out or waits for them to leave. I am not making these things up. These are all experiences of my own parishioners. Decades of this kind of treatment leave you tired, at best, or bitter and suspicious, at worst.

Yes, they are weak for the simple reason that they are the ecclesiological, liturgical, aesthetic, and devotional minority in the Church. That being said, perhaps with the exception of the more hardened Lefevrists, everything that they hold and desire is firmly rooted in the perennial teaching and tradition of the Church. They believe the same faith, receive the same sacraments, read the same Scriptures and pray for the health and intentions of the same Pope. So, again, St. Paul reminds us: “Now, we that are stronger ought to bear the infirmities of the weak and not to please ourselves” (Rom 15:1).

Liturgical War and Peace

St. Peter commands that we be “of one mind, having compassion one of another, being lovers of the brotherhood, merciful, modest, humble” (I Pet 3:8). If we are, indeed, to be of one mind and to reconcile with our brothers before offering our gifts (cf. Mt 5:24), I see two principle obstacles that need to be overcome. Both of these obstacles, by the way, are rooted in a lack of trust between those who favor the traditional liturgy and those who are perturbed by it.

The principle charge by those in favor of the traditional liturgy is that the reformed rites (or, at least, the celebration thereof) are not faithful to the Church’s own understanding of the nature and proper celebration of the Holy Mass. This perceived failing might be expressed in the lack of a sense of sacrality, mundane music, ‘performing’ priests and ministers, the versus populum orientation of the priest, the lack of silence and opportunity for prayer, the total exclusion of Latin and the chant tradition of the Church. Interestingly enough, I rarely hear any difficulties about the scriptures being read during the Liturgy of the Word in the vernacular. I do not think that the issue is the presence of the vernacular as much as the absence of Latin. The central point is this: walking into a traditional Mass, it is very clear that we are here to worship the Omnipotent God and to commune with things unseen. I think that any honest person will admit that it is sometimes much easier to read sacrality into the current celebration of the Mass than for it to naturally strike the congregant.

The principal charge of those who are hesitant toward the traditional liturgy is a bit harder to pin down. You hear some bile and wormwood from people who say that the “Latin Massers” hate Vatican II and the liturgical reforms a priori, but I do not really find this charge convincing. It is true that the abrupt implementation and abuses committed in the name of the Council have hardened many to the reforms, but I think that this posture is more fundamentally a reaction to certain bad fruits of the last 50 years than to the Council itself. A more convincing argument against the traditional liturgy than accusations of “bad attitude” is one of accessibility and community. It is true that it takes a bit of training to fruitfully assist at the Extraordinary Form. You have to learn what is happening and be comfortable with that fact that you are far from the center of attention. You also have to learn the communal aspect of the Mass springs first from the union of souls to God, then by means of God, to one another. The accessibility argument also speaks to the intended effect of the liturgical reforms: that Christ’s faithful should be led “ad plenam illam, consciam atque actuosam liturgicarum celebrationum participationem ducantur” (“to that fully conscious, and active participation in liturgical celebrations”).8 In the end, this charge is not new, and it is fair. It was the impetus for the liturgical reforms in the first place.

So, where do we stand? One side asserts that it has achieved the Council’s designs by making the Mass more accessible and communitarian. The other agrees, but notes that this was achieved by emptying the Mass of God. In a sense, their response is, “What’s the point? Better just to stick with what we know works.”

The irony in all of this is that the root of either’s hesitations ends up being the same thing. The people who are suspicious of the traditional form say that it somehow impedes them from adoring the Lord Jesus. The people who are suspicious of the ordinary form say that it somehow impedes them from adoring the Lord Jesus. Both sides want to adore the Lord Jesus and they are asking the same question, “How to best facilitate that?” Both sides want the same thing, and I think recognizing this common goal and dwelling upon it for a bit is the first clear step in overcoming some of the divisions and mistrust that continue to exist. The questions of sacrality and accessibility must be subjugated to the overarching principle that the Mass is the central means by which we adore God and are “made partakers of the divine nature” (II Pet 1:4).

To put the case in plain language, we have to recognize that we are on the same team: everyone that is going to Mass is going because they want to meet with Jesus the Lord. The Novus Ordo is a valid and currently predominant mode of that meeting. The Usus antiquior is also valid and the traditional expression of that same meeting. The two are not enemies.

Novus et Antiquior…

Happily, I think that we are at a point in time where we are moving beyond the tensions of Old Rite-New Rite in the generation of Catholics who are around my age (29 years old). We did not live through the so-called ‘Liturgy Wars’, most of us were not alive when Lefebvre consecrated the bishops, and the most horrible abuses are all just stories to us. We laugh at them, shrug and say, “That’s really weird.” Because we did not live through this history, we are not scarred and bitter. We do not necessarily see the Church divided into camps. We do not really know what the terms ‘Old Church’ and ‘New Church’ mean. For us, it is much more a question of what is Catholic or not Catholic.

Eucharistic adoration? —Great.

Praise and worship? —Great.

Latin chant? —Great.

Work with poor? —Great.

Small groups and evangelization? —Great.

Avoid nuclear war? —Great.

End abortion? —Great.

This young generation does not know anything about the tradition of the Church, about her music, art, architecture, devotions, or saints. When we do encounter them, we do not always think, “This is old.” In fact, we often think, “This is new. I had no idea that this existed.” This discovery should be a cause of joy for us, that the Church is always young, finding awe and wonder in places that we would not have expected or that we ourselves have discounted.

If we are to speak of “mutual enrichment,” we first have to be able to realize that both forms have something to offer to one another. Mistrust must be overcome before divisions can be healed. Mistrust is only going to be overcome if we can recognize each other’s arguments and hesitations, find what is valid, move beyond what is not, and understand—with good will—that the desire of all involved is to draw near to God and thus have communion amongst ourselves. If we are to be true to Benedict XVI’s hope of “an interior reconciliation in the heart of the Church,”9 we must understand Summorum Pontificum primarily as an instrument of ecclesial healing, and only after that as a contribution to the liturgical renewal.

Footnotes

- Benedict XVI, Letter Con grande fiducia (7 July 2007).

- Benedict XVI, Letter Con grande fiducia (7 July 2007).

- Joseph Ratzinger, The Feast of Faith (San Francisco : Ignatius Press, 1986), 61.

- Benedict XVI, Letter Con grande fiducia (7 July 2007).

- Paul VI, General Audience, 26 November 1969.

- LG 23.

- UR 4.

- SC 14.

- Benedict XVI, Letter Con grande fiducia (7 July 2007).