Holy Furniture

Together with the altar and ambo, the celebrant’s chair is considered one of the three principal liturgical furnishings in the sanctuary of every Catholic church, and frequently, the Church’s official documents give short theological explanations about the nature of each. The altar, for instance, stands as an image of Christ exercising his priestly office and gives a foretaste of the heavenly banqueting table. The ambo signifies the dignity of the Word of God proclaimed and magnifies its importance. The chair, too, has its own mystagogical role to play: the cathedra, or bishop’s chair, signifies the teaching, governing and sanctifying role of the bishop in his diocese as successor of the apostles.

By extension, every priest celebrant’s chair in a parish church signifies the priest’s headship during the sacred liturgy and his mission to sanctify and govern those in his care. The priest in his parish sacramentalizes Christ presiding as the head of the Mystical Body, and his chair indicates this role. As such, it is more than an everyday chair. It is a symbol of the invisible spiritual reality of the Father’s love so aptly described by Dom Lambert Beauduin: “Christ has transmitted all His power of teaching and of spiritual government to His visible hierarchy… [and] through it he realizes the sanctification of the new humanity.”1 The chair is a preeminent architectural sign not simply of authority, but of the spiritual power and responsibility given to the successors of the apostles to bring about Christ’s new humanity divinized with the very life of God.

Authority Takes Its Seat

We still speak of a chair as sign of authority. A king sits on a throne, a CEO sits at the head of the table, a chairperson leads a meeting, and a child sitting in his father’s seat at the dinner table is making a statement or playing a joke. Similarly, a scholar recognized for authoritative knowledge holds an endowed chair in a university or serves as department chair. But in Biblical terms, an earthly chair signifies a share in the authority of God who also reigns on a throne. Numerous heavenly revelations in scripture describe the Lord as seated on a throne, from the visions of Isaiah 6:1, Daniel 7:9-12 and Ezekiel 1:26, to the detailed description in the Book of Revelation (4:2-4).Scripture describes the Lord as being seated on his throne even on earth.2

The phrase “enthroned between the cherubim” (Is 37:16), in fact, was a name for God, whose earthly seat in the Jerusalem Temple was the Ark of the Covenant, guarded on each side by cherubim. The seat, then, was an image of God’s own authority, and, importantly, the authority he deputed to humanity to administer in his name. The scriptures are filled with stories of men who failed in using this authority well, but Christ eventually fulfilled this mission in the ultimate sense, giving explanation to Isaiah’s prophetic utterance about the Messiah, saying: “in love a throne will be established” and “in faithfulness a man will sit on it…, one who in judging seeks justice and speeds the cause of righteousness” (Is 16:5).

In the Old Testament, two examples illustrate the point well. First, in Genesis 41, Pharaoh looks for a wise man with whom to share his authority. Finding Joseph, he tells him that “only in relation to the throne,” that is, only in the kingly office, would Pharaoh’s authority be greater than Joseph’s. Second, God seeks out David and shares his own kingly authority with him by putting him on a throne. Terms like “throne of David” mean more than a particular chair, however, but instead speak of a long-lasting authority that spans many generations, just as the phrase “house of David” did not mean a domestic building but a family dynasty (see 2 Sam 7).

This dynasty itself, though, was a manifestation of God’s own governing of Israel, as Nathan is told that the Lord himself establishes the throne from which David rules and places him on it (2 Sam 7:13). When David dies, his son Solomon takes over as king, and as scripture puts it, “Solomon sat on the throne of his father David, and his rule was firmly established” (1 Kings 2:12). Even the limited description of the throne in 1 Kings speaks of its grandeur, being covered with ivory and overlaid with gold (1 Kings 10:18-20).3

This identification of a throne as a symbol of authority continues in the New Testament. When Jesus was brought for judgment, for instance, Pilate sat upon his judgment seat, indicating the authority given him by the Romans to govern the Jews (Jn 19:13, Mt 27:19). This symbol was potent enough that St. Paul would use the same term to describe Christ’s own authority as judge, noting in Romans 14:10-12 that Christians will someday face Christ when he sits on his eternal “judgment seat,” a notion reiterated in 2 Corinthians 5:10.

Chair as Symbol of God’s Shared Authority

In the realm of Jewish religious practice, the synagogue was known for its “Seat of Moses,” a chair mentioned by Christ as a place where the scribes and Pharisees gave the authentic interpretation of the law Moses (Mt 23:2). Though Christ speaks of the Seat of Moses in his caution against hypocrisy, it only emphasizes the fundamental notion of the chair as a symbol of a living authority which made the authority of Moses accessible centuries after his death. Twentieth-century liturgical scholar Louis Bouyer understood the importance of the Seat of Moses as more than a piece of furniture, since from it “the word embedded in a tradition still alive could be received.”4

The seat was not simply a human-derived sign of office but a theological concept indicated by a material object rendering knowable to the senses that “there was always among them some one held as the authentic depositary of the living tradition of God’s word, first given to Moses, and able to communicate it always anew, although substantially the same.”5 Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger gave strong support to Bouyer’s claims in his 2000 book The Spirit of the Liturgy, reiterating that the rabbi was not simply a professor analyzing the Word of God on his own authority, but the means through which “God speaks through Moses today.” The chair made clear that the event in which God gave the law to Moses on Mount Sinai was “not simply a thing of the past” but God himself speaking.6 In other words, God does not abandon his people after he gives the law. He allows a living authority to continue, and this authority is signified by a chair.

The proper use of this authority, of course, is directed to the glorification of God and bringing humanity to its eschatological fulfillment. Christ himself speaks of the end times in the context of chairs, noting that the time will come when he sits on a glorious throne and the apostles will sit in thrones near him in heaven (Mt 19:28). Christ’s reign in heaven provides the ultimate accomplished fulfillment of the offices of priest-sanctifier, prophet-teacher and king-leader. The Old Testament foretold it and the events of the Paschal Mystery made it accessible to human beings. Yet as Christ reigns in heaven, he gives this threefold power to his Church, entrusting it to its visible hierarchy: the successor of Peter and the successors of the apostles. The Chair of Peter presides over the chairs of the bishops, the chairs of the bishops preside over the chairs of priests in parishes, and the chairs of priests indicate their presiding over those who sit in the pews. And, of course, the throne of Christ presides over it all.

The Charity of Chairs

The word “preside” can sometimes sound harsh in the liturgical context, especially since many translations use the phrase “preside over” to describe the priest or bishop’s relationship to the people. For a time it was fashionable to call the priest celebrant’s chair the “presider’s chair,” and some took offense, thinking it could be interpreted as diminishing the dignity of priestly ordination. The Order for A Blessing on the Occasion of a New Episcopal or Presidential Chair from the Book of Blessings calls the chair the “place for the presider,” then immediately follows up by saying “that is, the chair for the priest celebrant.”7 Similarly, the General Instruction of the Roman Missal speaks of the chair of the “Priest Celebrant” and indicates that it “must signify his presiding over the gathering” (par. 310, italics added), a phrase which appears in the Catechism of the Catholic Church almost verbatim (CCC, 1184). What, then, does it mean to “preside” and how does a chair signify that role?

Though research on the term itself seems to be quite scarce, the context of the Church’s use of the term preside appears to indicate headship, not simply in the functional sense, but the sense indicated by the Liturgical Movement’s rediscovery of the liturgical implications of the Mystical Body. Much of the theological justification for the critical importance of active participation of the laity was the rediscovery that the Mass was offered by the priest and people together, with the priest sacramentalizing the headship of Christ (in persona Christi capitis) and the laity the members of Christ’s body (in persona Christi). Presiding, then, appears to be the Liturgical Movement’s theologically rich word for the nature of priestly activity: priests take the prayers and oblations of the priestly people to the altar and offer them to God as Christ the head. “Preside” then indicates the conciliar interest in the conscious and active participation of the people, as indicated in a short line in Inter Oecumenici, the 1965 document from the Sacred Congregation for Rites on the implementation of Sacrosanctam Concilium: “In relation to the plan of the church, the chair for the celebrant and ministers should occupy a place that is clearly visible to all the faithful and that makes it plain that the celebrant presides over the whole community” (par. 92).

The phrase “whole community” gives the important clue for proper interpretation. Rather than reading the phrase “preside over” as lording authority over the people, it means headship of the whole community, including the laity. The chair therefore becomes a sign that makes clear in liturgical furnishings the phrase “my sacrifice and yours.” Consequently, according to statements in the General Instruction of the Roman Missal as well as the Book of Blessings, the chair indicates not only presiding, but also “directing” or “guiding” the prayer of the people (GIRM, pr. 310; BB par. 1154) as the head of the body gathers up and offers the prayers of the whole community and directs them to God. Presiding, then, takes a certain hierarchical order in love.8 Christ is the head over the Church, the pope presides over the bishops, the bishop presides over his priests, the priest presides over his people, and, one might add, the parent (biblically, the father), presides over the family.

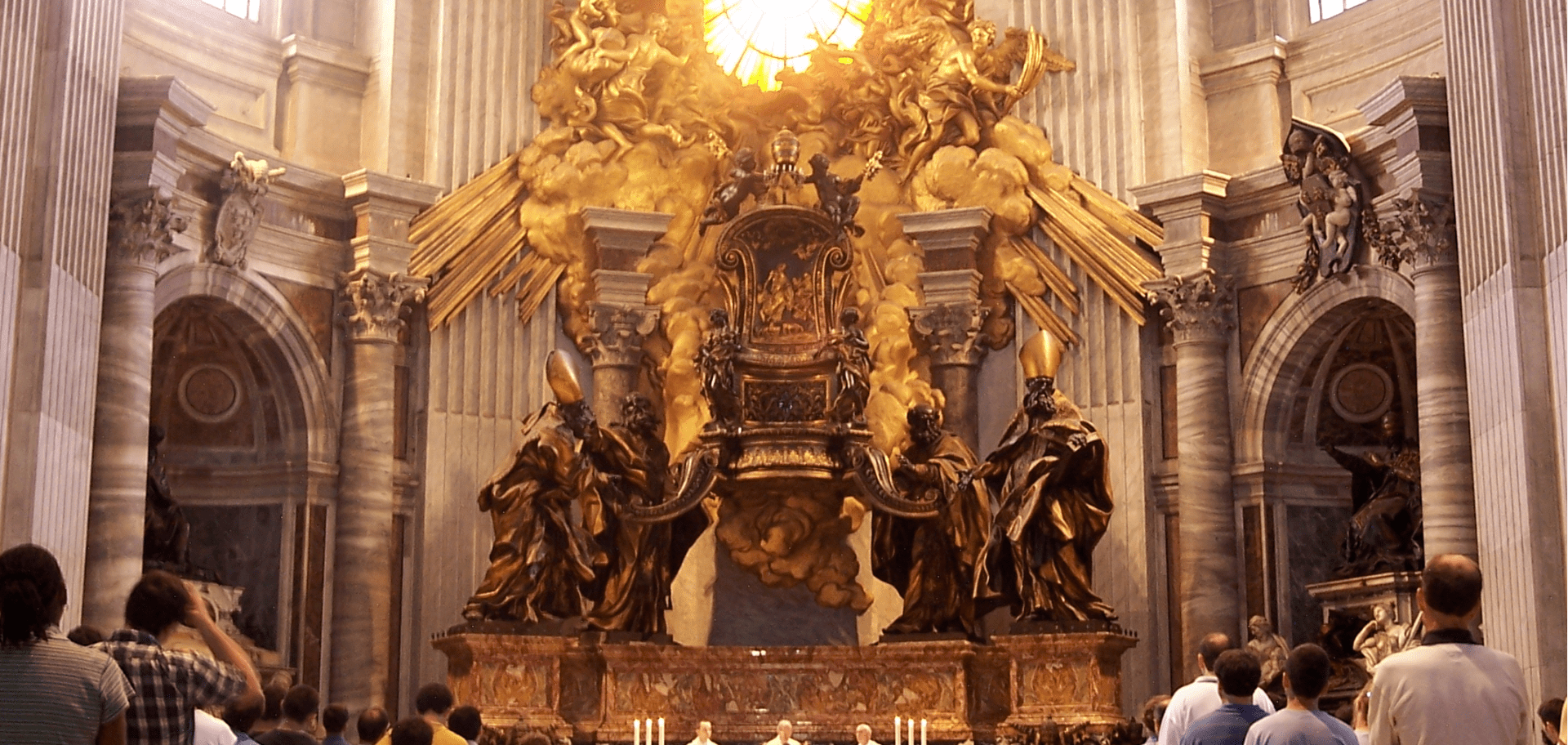

Cathedra Petri

In the Catholic tradition, the pope, the holder of Peter’s authority, is symbolized by a chair, even to the existence of the Feast of the Chair of Peter the Apostle, celebrated in the Roman calendar on February 22. In fact, Gianlorenzo Bernini’s monumental 1667 Cathedra Petri in the apse of Rome’s St. Peter’s Basilica is a monumental shrine enclosing an ancient papal chair. It not only provides a setting for the veneration of a relic, but, in a fulfillment of the Seat of Moses, proclaims to the world that the authority of Christ given to Peter is still operative in the world. Indeed, when the pope proclaims a new dogma at the highest level of authority, he is said to speak ex cathedra, or “from the chair.” He speaks not only of his own theological speculation, but with the guaranteed authority of the Petrine office. This teaching and governing authority of the Petrine office, though, is one of service in charity meant to build up the members of the Church, just as Peter’s authority edified the other apostles. The entrance antiphon from the Feast of the Chair of Saint Peter states this reality clearly: “The Lord says to Simon Peter: I have prayed for you that your faith may not fail, and, once you have turned back, strengthen your brothers.”

Pope Benedict XVI quoted this very phrase in his homily at the Mass of Possession of the Chair of the Bishop of Rome on May 7, 2005, the formal occasion when he “took possession” of the Diocese of Rome and its cathedra at the Basilica of Saint John Lateran. “The Bishop of Rome sits upon the Chair to bear witness to Christ,” he said. “Thus, the Chair is the symbol of the potestas docendi, the power to teach that is an essential part of the mandate of binding and loosing which the Lord conferred on Peter, and after him, on the Twelve.”9 He cited Ignatius of Antioch, who spoke of the Church of Rome as “she who presides in love” (italics added), stating: “presiding in doctrine and presiding in love must in the end be one and the same: the whole of the Church’s teaching leads ultimately to love.” Presiding, then, is an act of love of the head for the body, as Christ loves his body the Church. Benedict repeated: “The Chair is—let us say it again—a symbol of the power of teaching, which is a power of obedience and service, so that the Word of God—the truth!—may shine out among us and show us the way of life.”

A feature of God’s love for his people is giving the new Seat of Moses to the Church in the Petrine office. “In the Church,” Benedict preached, “Sacred Scripture, the understanding of which increases under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, and the ministry of its authentic interpretation that was conferred upon the Apostles, are indissolubly bound.” Here Pope Benedict reiterates a continuous line of thought from the Second Vatican Council’s document Christus Dominus, which states in paragraph 2: “In this Church of Christ, the Roman pontiff, as the successor of Peter, to whom Christ entrusted the feeding of His sheep and lambs, enjoys supreme, full, immediate, and universal authority over the care of souls by divine institution. Therefore, as pastor of all the faithful, he is sent to provide for the common good of the universal Church and for the good of the individual churches. Hence, he holds a primacy of ordinary power over all the churches.”10

The Petrine Office, then, evidences God’s care for his universal Church, and is symbolized by the grandest chair in Christendom.

What Sitting Bishops Stand For

The bishop’s chair, or cathedra, grows out of the Church’s hierarchically arranged system. Indeed, the word cathedral, properly speaking, is an adjective which has become a noun from a shortening of the phrase cathedral church, the church in which the cathedra resides. Under the headship of Peter’s successor, it signifies the bishop’s office and the Christ-given power, handed on from the apostles through the laying on of hands, to teach, sanctify and shepherd by presiding over his college of priests and the faithful (SC, 41, italics added). Christus Dominus states a bishop’s ontological reality clearly: “The order of bishops is the successor to the college of the apostles in teaching and pastoral direction…. Together with its head, the Roman pontiff, and never without this head, it exists as the subject of supreme, plenary power over the universal Church” (CD, par. 4).

As successors of the apostles, bishops do what the apostles were called to do: govern, teach and sanctify (see CCC, pars. 880-896). The prayer for blessing a cathedra calls this mission a “sacred ministry” which grows out of God’s goodness toward his people, and asks God to make the bishop who sits on it worthy to “teach, sanctify and shepherd the faithful” (BB, par. 1158). Moreover, his chair signifies his role as chief liturgist of the diocese; Sacrosanctam Concilium notes that the bishop is “to be considered as the high priest of his flock, from which the life in Christ of his faithful is in some way derived and dependent. Therefore all should hold in great esteem the

liturgical life of the diocese centered around the bishop, especially in his cathedral church” (SC, 41).

The office of bishop evidences the extension of the headship of the Mystical Body out to all corners of the world, and is symbolized by the grandest chair in each diocese.

Sit Down and Celebrate

Though many bishops govern the world’s nearly 3,000 dioceses, “it is impossible for the bishop always and everywhere to preside over the whole flock in his Church,” Vatican II says, “and so he cannot do other than establish lesser groupings of the faithful.” The most important of these smaller groupings are parishes, because “they represent the visible Church constituted throughout the world” (SC, 42). As an extension of each diocese’s cathedral church and its cathedra, each parish church contains a priest celebrant’s chair to indicate that the bishop’s ministry is exercised at the local level. This chair reveals and proclaims the priest’s critical sacramental role in gathering the worshippers’ offerings of themselves to God then directing their prayer to the Father. Priests “participate in and exercise with the bishop the one priesthood of Christ and are thereby constituted prudent cooperators of the episcopal order,” says Vatican II (CD, 28). Therefore the local pastor also exercises the duty of teaching, governing, and sanctifying (CD, 30).

Just as the priest is related to the bishop in his authority exercised at the parish level, so the priest celebrant’s chair can be said to have a sacramental relation to the bishop’s cathedra. The deacon’s chair follows along this line of subsidiarity, having a subordinate relation to the priest’s chair. Similarly, one might say the pews of a church have a theological relation to the celebrant’s chair, since the task of teaching, governing and sanctifying strengthens the laity with grace which is then exercised in the world and the home.

This ministry of the Father’s love happens at the local level and is symbolized by the grandest chair in the church.

Who Sits Where (and Why)

The Church gives broad principles rather than specific instructions about the design of a cathedra or priest’s chair, allowing the logic of use and design of each to grow from the nature of the thing itself. Logically, since each diocese has only one bishop, there is one cathedra in a cathedral and indeed in each diocese. Again, logically, only the diocesan bishop (or as the documents say “a bishop he permits to use it”)11 would sit in a cathedra, so a priest who celebrates Mass in a cathedral would sit in a different chair, leaving the cathedra unoccupied. But like the seat of Moses, the “empty” chair remains a symbol of the continuing ministry of the apostles precisely in its emptiness. The Ceremonial of Bishops notes that it should be a “chair that stands alone and is permanently installed” (par. 47) which may be raised up some steps in order to be seen, giving it the prominence of the office of bishop and reinforcing the permanence of Christ’s authority residing in the successors of the apostles.

In the parish setting, the logical consistency of the ecclesiastical hierarchy follows. A church normatively has only one celebrant’s chair since each Mass has only one principal celebrant, and should a layperson lead another liturgical rite or devotional prayer, he or she does not sit in the priest-celebrant’s chair.12 The deacon’s chair is to be placed near the priest’s chair, but seating for other ministers is meant to be clearly separated to clarify their role and to make the exercising of their ministry convenient (GIRM, 310). In a conspicuous exception, a deacon who presides at a Sunday Celebration in the Absence of a Priest or another liturgical rite “sits in the presidential chair.”13

The Ceremonial of Bishops does not give a specific location in the cathedral for the cathedra, though it recommends placing it where it is clear that the bishop is “presiding over the whole community of the faithful” (par. 47), reiterating the notion of the headship of the bishop joining to himself the body of faithful in his diocese. In individual parish churches, the General Instruction gives a clear preference to placement of the priest celebrant’s chair “facing the people at the head of the sanctuary” (par. 310), though it quickly gives alternative possibilities in the case of the chair being too far from the altar or “if the tabernacle were to be positioned in the center behind the altar.” The current General Instruction of the Roman Missal also states clearly that “any appearance of a throne is to be avoided” (par. 310) in a parish setting, because this is the prerogative of a bishop.14

When properly designed, all liturgical things lead the minds of the faithful from material things to invisible spiritual realities they manifest. This clarity of external presentation allows the structure of the Church’s arrangement to be displayed for the faithful by symbolizing, making knowable to the senses how God choses to continue the redemptive activity of Christ in the world. Christ’s mission of sanctifying, governing and teaching continues in hierarchy of the Church, and liturgical furnishings both support this activity and make it clear. In the divinely organized pattern of self-communication, the chair—from throne of Christ to the humblest pew—speaks of the diffusion of God’s own life in love to his chosen people.

Denis McNamara is Associate Director and faculty member at the Liturgical Institute of the University of Saint Mary of the Lake / Mundelein Seminary, a graduate program in liturgical studies. He holds a BA in the History of Art from Yale University and a PhD in Architectural History from the University of Virginia, where he concentrated his research on the study of ecclesiastical architecture of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He has served on the Art and Architecture Commission of the Archdiocese of Chicago and works frequently with architects and pastors all over the United States in church renovations and new design. Dr. McNamara is the author of Catholic Church Architecture and the Spirit of the Liturgy (Chicago: Hillenbrand Books, 2009), Heavenly City: The Architectural Tradition of Catholic Chicago (Liturgy Training Publications, 2005), and How to Read Churches: A Crash Course in Ecclesiastical Architecture (Rizzoli, 2011).

Footnotes

- Dom Lambert Beauduin, OSB, Liturgy The Life of the Church, (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1926), trans. Virgil Michel, OSB, 1.

- Enthronement language for God is extraordinarily common. For notable examples, see Psalms 2, 7, 9, 22, 29, 55, 61, 80, 99, 102, 113, 123, and 132 where typical expressions include phrases such as “God reigns over the nations; God is seated on his holy throne” in Psalm 47:8. Ezekiel 1:26 and Daniel 7:9-12 similarly describe the vision of the Lord enthroned in heaven.

- Kings 10: 18-20: “Then the king made a great throne covered with ivory and overlaid with fine gold. The throne had six steps, and its back had a rounded top. On both sides of the seat were armrests, with a lion standing beside each of them. Twelve lions stood on the six steps, one at either end of each step.”

- Louis Bouyer, Liturgy and Architecture, South Bend, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1967), 11.

- Bouyer, 11.

- Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy, (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2000), 64.

- “Order for A Blessing on the Occasion of a New Episcopal or Presidential Chair,” Book of Blessings, par. 1154.

- For a thorough investigation of the concept of priestly hierarchy in love, see Matthew Levering, Christ and the Catholic Priesthood Ecclesial Hierarchy and the Pattern of the Trinity (Chicago/Mundelein: Hillenbrand Books, 2010).

- Homily of His Holiness Benedict XVI, Mass of Possession of the Chair of the Bishop of Rome, Basilica of St John Lateran, Saturday, 7 May 2005. Accessed at https://w2.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/homilies/2005/documents/hf_ben-xvi_hom_20050507_san-giovanni-laterano.html.

- Second Vatican Council, Decree on the Bishops’ Pastoral Office in the Church (Christus Dominus), par. 2.

- Ceremonial of Bishops, par. 47.

- See Built of Living Stones Guidelines of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops [BOLS], (Washington, DC: United States Catholic Conference, 2000), par. 64: “The [chair] is not used by a lay person who presides at a service of the word with Communion or a Sunday celebration in the absence of a priest. (Cf. Congregation for Divine Worship, Directory for Sunday Celebrations in the Absence of a Priest [1988], no. 40).”

- Order for Sunday Celebrations in the Absence of a Priest, 38.

- Although the General Instruction of the Roman Missal does not quote it fully, at this point it gives a footnote to Inter Oecumenici (1965) which reads: “Should the chair stand behind the altar, any semblance of a throne, the prerogative of a bishop, is to be avoided” (par. 92).